New Delhi: Growing up in Delhi, Vanshika Mittal never planned to study abroad. But K-pop changed the trajectory of her life. After completing her BSc in microbiology from Delhi University in 2021, she didn’t jostle for admissions to India’s already choked universities or look at US or UK institutions, as many affluent young people do. Instead, she took an unusual gamble. Mittal tested how far her music taste could take her. K-pop first led her to learn the language, then propelled her to South Korea for higher education, making the language more than just a hobby for her.

Once she discovered that science wasn’t her true calling, Mittal, now 24, enrolled for an online Korean language course at King Sejong Institute, Manipur. It was a necessary detour since the Delhi Korean Culture Centre was full to the brim. Her dedication paid off. After completing seven out of eight levels and interning at the South Korean Embassy in Delhi, Mittal clinched the prestigious Global Korean Scholarship (GKS) for a master’s in Korean language education last year.

“I had an interest in languages since I was young. I learnt Sanskrit and French in school. Later in college, I dabbled in a bit of German on my own. I began listening to K-pop, including a lot of BTS, around 2019. During the pandemic, I got more into it and subsequently joined the online classes (to learn Korean),” Mittal said over the phone from her dormitory in Seoul.

Mittal has now become an ambassador for pulling more K-pop and K-drama fans to South Korean universities, which have been striving to fill the gaps in their international student pool. The hallyu wave is meeting higher learning.

These days, however, Mittal’s demanding study schedule leaves her little time to indulge her passion for BTS, Blackpink, and other K-pop bands. While glossy pop culture may be the gateway for many international students, Korean universities expect them to be serious about academics.

“That’s also one of the major aspects that universities and the embassy take into consideration when you apply,” she said. “They look at your actual purpose of coming to Korea.” In her case, the motive was the language. “Once I began learning the [Korean] language, I discovered that the script was created in a scientific manner. That’s when I began going through research papers on the Korean language and here I am today.”

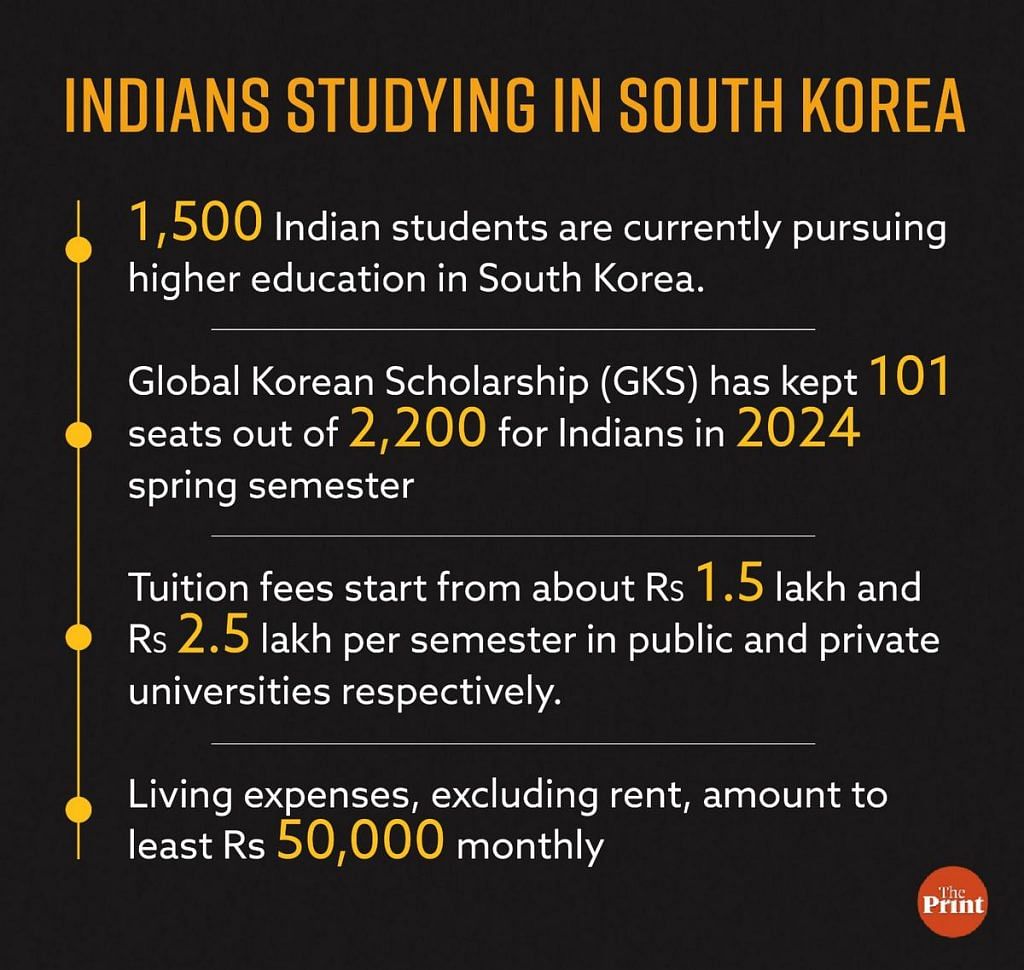

Mittal is one of nearly 1,500 Indian students currently pursuing higher education in South Korea. This number pales in comparison to the 68,000 Chinese students or even 2,300 Nepali students studying there. But an understudied yet important shift is taking shape.

A segment of India’s huge K-pop and K-drama community—lapping up Korean language, food, beauty, fashion—is now set to seamlessly transition into a vibrant student community to bridge Korea’s impending skilled workforce deficit. As it grapples with an aging population and dipping birth rate, South Korea has found a smart way of leveraging its cultural soft power to establish itself as an education destination.

They respect India’s IT prowess and their minds. The general image of India in Korea’s mind is that Indians are very good with Maths and IT

-Satyanshu Srivastava, GKS India Alumni Association president

But for Indian families obsessed with sending their children to the US, UK, Canada, or Australia, South Korean universities present a cultural challenge to wrap their heads around. Further complicating the picture is the country’s focus on attracting students in STEM fields over arts and humanities.

South Korea is looking to get 3 lakh international students from around the world by 2027 and in turn secure skilled foreign workers for its high-tech industries. As part of this big plan, they are also targeting Indian students. Another surge of interest in South Korea is expected with the inclusion of the East Asian language in India’s National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

Currently, students make up only a small slice of the Indian community in South Korea. There were 13,585 Indians living in the country as of last October, according to External Affairs Ministry data. Of these, 349 are classified as persons of Indian origin (PIOs) while the rest are NRIs. Additionally, there is a significant “floating population” of Indians in South Korea, with most coming on employment visas for 1-3 years with multinational companies. While the Korean embassy in India estimates the Indian student population to be around 1,500, the student support non-profit Indian Students and Researchers in Korea (ISRK) claims the number could be as high as 3,500 for the academic year 2023-24. “In 2023, the Embassy had circulated a registration form but I guess many have not registered in that,” said ISRK vice president Iqbal Khazi.

Beyond universities in the capital Seoul, some provincial governments in South Korea are also bullish in attracting Indian students. Last year, the governors of Gyeonggi and Gyeongsangbuk provinces visited India, with student recruitment among their agendas.

“The education sector is very important for our bilateral relations,” said Chang Jae-bok, the South Korean Ambassador to India, during a media interaction last month. “The future of our relations depends on educational cooperation. We already have many students, teachers, and scholars between our two countries. I can see a bright future ahead of us whenever I interact with young Indians who are studying in Korea and (the) Korean language.”

Getting a work visa is generally seamless for anyone with a degree from a Korean university.

Also Read: K-pop to K-dramas, there is a new K in the life of Indians – it’s Korean language

Irresistible GKS scholarship

Last month, a Latin American woman studying on the Global Korean Scholarship went on an Instagram rant. The reason: she was flooded with queries from Indians in the run-up to the application deadline.

The coveted Korean government-sponsored GKS scholarship—covering tuition, living expenses, health insurance, airfare, and a research grant—had ignited a frenzy among Indian students, she told ThePrint.

“There were messages asking for very basic, very Google-able stuff. Maybe I’ve answered around 100-something people, give or take,” said the student, who didn’t wish to be named.

The undergraduate student, who has been studying in South Korea since 2020, had received GKS-related inquiries before, but this deluge from India was unprecedented.

“This time, I think two or three of my reels got pushed to the Indian region algorithm,” she speculated. “My followers or people that engage the most were from the US and now it shifted to India.”

South Korea has nearly 400 institutions of higher learning, including junior colleges and private and public universities—a huge number for a country that’s even smaller than Odisha. The Korean obsession with education is also reflected in their marathon eight-hour college admission test, known as Suneung. On exam day, traffic gets suspended, flight timings are readjusted, and everyone makes way for students to reach their test centres on time.

The country prides itself on its educational excellence, with six universities standing within the top 100 of the QS World University Rankings as of 2023. Seoul National University leads the pack, holding the 29th position globally. In contrast, India’s top ranker, the Indian Institute of Science, lags at 155th place, with eight Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) following suit within the top 400.

“The quality of education in Korea is very high. The literacy rate is almost 100 per cent and Koreans in general pay specific focus on studies. That has been happening since traditional times,” said GKS India Alumni Association president Satyanshu Srivastava, who did his PhD from Seoul National University and is currently an assistant professor at the Centre for Korean Studies in Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

In 2006, Srivastava was one of the two Indian students who had secured the GKS, known back then as the Korean Government Scholarship Program (KGSP). The first scholar to go to South Korea on the scholarship from India, he said, was Vyjayanti Raghavan (who was a professor at JNU’s Centre for Korean Studies) in 1976.

Korea is doing great work. They are investing in emerging research areas like quantum science and technology. Naturally, people have started looking East

-K Shree, postdoctoral student

From then until 2007, the GKS was typically awarded every year to only one or two students in the fields of Korean language, literature, and cultural studies. Then came a sudden increase in the number of seats for Indians.

“In 2008, Korea suddenly opened up the scholarship. They offered 50 seats for India,” Srivastava said. Although the quota for Korean studies remained the same, students from science fields also became eligible to apply for the GKS. Now, biosciences, life sciences, computer science, public administration, and information technology are some of the most popular choices among Indian GKS applicants.

In the Korean popular imagination, Srivastava said, India and STEM fields are seen as having a symbiotic relationship.

“They respect India’s IT prowess and their minds. The general image of India in Korea’s mind is that Indians are very good with Maths and IT,” he added.

Today, India is one of the leading recipients of GKS scholarships, trailing only China and Indonesia. According to the resource site for the scholarship, there are 101 scholarship slots available for Indian students out of the total 2,200 offered for the Spring 2024 semester. The South Korean embassy will choose 28 students, while the remaining 73 will be selected directly by universities.

Vanshika Mittal secured admission to Kyung Hee University through the embassy track in 2023.

Mittal was shocked when she discovered that a single mango cost the equivalent of Rs 300 in Korea. As a vegetarian, this was a harsh reality to digest.

‘Easy’ work visas, good quality of life

K Shree, a 29-year-old from Delhi, moved to South Korea just when the Covid pandemic started in March 2020. Pop culture wasn’t the catalyst for her. Instead, it was an opportunity to pursue a PhD at the University of Science and Technology (UST) in Daejeon, a city 140 kilometres from Seoul.

After a master’s from an IIT, the West was the conventional option for further studies, but she wasn’t accepted into the top universities. Then, while researching papers in her field, quantum studies, she stumbled upon exciting work being done in South Korea. One thing led to another and she made her way to Daejeon, working alongside other international researchers in a well-funded laboratory.

“In the field of science, visibility of the research is an important factor. High-impact publications contribute to gaining that visibility. And Korea is doing great work. They are investing in emerging research areas like quantum science and technology. Naturally, people have started looking East,” she said.

Her PhD was a smooth sail and accomplished within three years. The transition to a post-doctoral position followed soon thereafter. Getting a work visa is generally seamless for anyone with a degree from a Korean university.

After their master’s or PhD degree, foreign students are usually offered a six-month D-10 visa— the Korean equivalent of a post-study or job seeker’s visa, Srivastava said. This can be upgraded to a work visa if they secure a job within that time frame.

Shree’s Korean journey might be considered unusual as she has navigated the country for nearly four years despite barely speaking a word of Korean. Language apps, technology-friendly stores, and “very kind and understanding” Koreans have all enabled her to get by smoothly.

“The system is such that you don’t necessarily need to know Korean,” she said. “My friends who study in Europe have been met with hostility for not knowing the local language. But in Korea, people are so considerate and helpful.”

Over the years, she has been able to communicate effectively with real estate agents and landlords, and enjoys activities like swimming, yoga, and kickboxing. While she doesn’t intend to stay in South Korea permanently, she has met many Indian expatriates who initially came to study and are now raising families there.

“There’s good money and one can enjoy a good quality of life. The visa rules and immigration laws are such that Korea wants foreigners to stay long-term,” Shree said.

South Korea has astutely monetised its soft power, taking it from concert halls and conventional tourism to classrooms through short-term language and culture programmes.

The ability to roam fearlessly at night, convenient public transportation, and access to nutritious meals on campus are some of the small joys that Shree and Mittal enjoy in their respective cities. Both agree that it’s a contrast to their experiences in Delhi.

Mittal’s most “impressive” anecdote of her Korea experience is the time she accidentally pocket-dialled the emergency number. The police station immediately called her back to confirm her safety.

“They even came to my location to check, though I told them I am fine. The police showed up at the place where I was having lunch. They take safety so seriously,” she recalled.

Also Read: K-pop in Ekta Kapoor serials — the Korea-India YouTube boom no one saw coming

Enticing offers, but what’s stopping Indians?

Delhi’s K-culture enthusiasts had a treat last May when Indian and Korean college students took to the stage at Kamani auditorium, showcasing everything from taekwondo to K-pop dances. This event, however, was more than just entertainment. Accompanying the Korean students was Gyeongsangbuk governor Lee Cheol-woo, and he was on a mission.

At the event, Lee said they were looking forward “to create more opportunities for Korea and India to harmonise more”. Away from media attention and publicity, the governor was already working toward it. He visited JNU’s Centre for Korean Studies, the oldest institution in South Asia offering Korean language programmes from undergraduate to PhD levels. There, he met with professors and conveyed his interest in attracting Indian students to universities in his province.

Two months later, JNU received another visit, this time from Gyeonggi province governor Kim Dong-yeon.

“They were assuring jobs and settlement, not just for the student but the whole family. They want the whole family to come and settle there for a certain time, and have kids,” JNU professor Srivastava said. “They are eyeing skilled workers from India, for both white- and blue-collar jobs.”

Despite these tempting offers, the number of Indian students in South Korea remains abysmally low. And it’s a concern Korea isn’t taking lightly. Last month, two professors from Korea University, one of the country’s premier institutions, visited JNU to investigate the reasons behind these low numbers.

But Srivastava said the reason was simple: “If our students had the money to pay your tuition fee, they would rather go to the US, UK, Canada or Australia.”

Higher education in Korea is a costly affair compared to India. Tuition fees for courses in public universities start from over Rs 1.5 lakh per semester. As for private universities, the fees generally begin at Rs 2.5 lakh per semester and can climb even higher depending on the programme. Living expenses, excluding rent, reach at least Rs 50,000 per month.

Mittal was shocked when she discovered that a single mango cost the equivalent of Rs 300 in Korea. As a vegetarian who enjoyed a diet rich in fruits back home, this was a harsh reality to digest. To this day, she hasn’t purchased the pricey mangoes or melons, but has spent up to Rs 600 on four apples.

Other than the cost factor, Srivastava said Korea still has to go “some more distance” in portraying itself as a desirable education destination. In India, he pointed out, English-speaking countries with good infrastructure and strong institutions generally take precedence over those in the East.

The share of people going to South Korea on student loans or personal funds is still very low. The majority of them still rely on scholarships, project support, or university tuition waivers.

Geopolitics may also play a small role. In Srivastava’s experience, families in India associate “Korea” with North Korean threats, Kim Jong Un, and the worrying visuals “they see in the news all the time”. So, while Korean dramas and K-pop entice some Indians, the negative image of a belligerent North Korea lurking across the border creates a counterpoint.

However, there are new pull factors too, such as the introduction of Korean as a foreign language in the National Education Policy 2020. Srivastava foresees a huge demand for Korean language teachers and instructors from schools across India “riding the Korean craze”.

Exposure to the language and culture in turn is expected to deepen Indian interest in Korea further. It’s a fad Srivastava doesn’t see fading in the next 10-20 years.

“Beyond that time, I am not sure if K-pop or K-dramas will (stay so popular). There might be something new because trends change every day and the attention span also of the current generation is very TikTok,” he said.

Also Read: Big K-pop stars aren’t coming to India and it’s because fans aren’t rich enough

Broadening Hallyu market

South Korea has astutely monetised its soft power, taking it from concert halls and conventional tourism to classrooms through short-term language and culture programmes. While drawing skilled workers through generous scholarships and research funding might be the ultimate goal, numerous South Korean universities and private institutions also offer short-term courses to keep money coming.

These options are snapped up by those who want an immersive learning experience in the country, but without a major time or financial investment.

Advika Mathur, a 27-year-old who had already completed a two-year Korean language course at Delhi University, was keen to hone her skills in South Korea but wanted to avoid a long-term commitment.

“I lacked confidence and command over the language but I didn’t want to do a long-term degree, which involved writing a thesis. So, I enrolled for a short-term language course at Seoul National University (SNU),” she said.

Tuition fees for language programmes at SNU start from about Rs 90,000 per semester.

By enrolling for four semesters of a language and culture programme at SNU starting March 2021, Advika benefited from a well-rounded Korean experience. Upon returning to India, she not only achieved the highest level of proficiency (TOPIK Level 6) in Korean, but also snagged a job at the Korean Cultural Centre India (KCCI), where she worked until last year.

Unlike Advika, 29-year-old Suranya Sur’s interest in Korea began with food. Frequent visits to the cafe at KCCI led to her learning about the language course offered at the centre. At the time, she said, she wasn’t looking for a “regimented course” but thought it would add to her resume as a content writer. It turned out to be more than that.

Sur excelled at the course, even earning a fee waiver. After two years, she was confident enough in her skills to take off on a three-month trip to Korea last year on a short-term study visa coupled with a tourist permit.

During her visit, she spent around Rs 3.7 lakh for a two-month intermediate language course at Seoul’s Rolling Korea Institute, inclusive of basic accommodation, pickup from the airport, and opportunities to participate in cultural activities, events, and tours around the city.

“There is a burgeoning rise in South Korea’s soft power and it has opened its doors to the world. However, it’s still a closed-knit community, so knowing the language helps,” Sur said. “Koreans respect you if you know their language. It means you have done your bit.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

This this is so amazing news and post thank you so much I love this so much should it for Korean and kpop singing all so beautiful yesterday and country