Hyderabad: Every monsoon, drain water invaded Ranjeeta Dhanapalan’s home in Hyderabad’s Paigah Colony, destroying everything inside and leaving a stench behind. For 30 years she begged officials to help, but nobody heard her. Then came the Hyderabad Disaster Response and Asset Protection Agency, or HYDRAA, a new state force to tackle urban flooding, encroachments, and other issues assailing the growing city.

“We were afraid that HYDRAA would prove to be like any other government agency, but our complaint was taken seriously and the root cause of our issue, which was encroachment, was resolved,” Dhanapalan said. She recounted that after residents met the commissioner, IPS officer AV Ranganath, last year, he personally surveyed the area and spoke to stakeholders. Soon after, JCBs rolled in to raze a multi-storey commercial complex choking the drains.

With a Singham-style approach, perched on bulldozers, HYDRAA, Hyderabad’s rebranded disaster response agency, is ruthlessly demolishing ‘illegal’ constructions and reclaiming lakes, parks, and government land. It is digging into archival maps and historical records to trace long-lost lakes and nalas. It wants to rescue Hyderabad’s water bodies from decades of constructions and encroachments.

It is easier said than done.

Some call it a systemic abuse of powers by the Congress government; others see it as a necessary bold move in the face of frequent disasters. In various states, slums, illegal settlements, and even historical structures have been subjected to bulldozer raj. There is always politics that trips every urban transformation push. But HYDRAA wants to save Hyderabad from itself.

A month after the agency was formed in July 2024, Deccan Herald declared that HYDRAA had caused “tremors” in Telangana politics. In the state assembly, former finance minister T Harish Rao accused the agency of being “weaponised” against BRS legislators. A South First cartoon showed Rahul Gandhi’s ‘mohabbat ki dukaan’ flattened under Chief Minister Revanth Reddy’s bulldozer. Ex-Congress leader Judson Bakka even moved the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) about people being made homeless by the removals.

“I am giving water its way to flow freely,” CM Reddy told ThePrint editor-in-chief Shekhar Gupta a few weeks ago, speaking about HYDRAA’s formation. “Lake encroachment, nala encroachment, whoever is doing it… no matter how influential the person, no matter if it’s the Prime Minister, I won’t stop.” Thus summarising the philosophy HYDRAA is built on.

Also Read: Brand Bengaluru is stuck on bad roads. MNCs, startups are saying ‘Hello Hyderabad’ now

Cheered and feared

From BRS leaders like Sai Raju to AIMIM MLAs such as Mohammad Mudeen to actor Nagarjuna, HYDRAA’s wrath spares no deemed offenders.

In its first year, the agency has invited both applause and fury. Many historians and environmentalists have cheered, while some activists accuse it of being a political intimidation tool.

Formed by government order in July 2024, HYDRAA has reclaimed 500 acres of land in Hyderabad, mostly to revive lakes lost to decades of encroachment by politicians, real-estate developers, and local mafias. These demolitions aren’t to clear land for new construction but to reopen stormwater drains and revive lakes.

Initially, we faced resistance and even received legal notices, but the government recognised the need to empower us

AV Ranganath, HYDRAA commissioner

Urban flooding isn’t just about dirty puddles and traffic snarls caused by waterlogging. Indian cities are fatally unprepared for heavy rain. Every year, deaths are reported almost like clockwork. Last month, an auto driver in Gurugram died after falling into an open drain when the city was flooded. A landslide hit a housing society in Mumbai’s Vikhroli and killed two after a downpour. In Delhi this week, a 40-year-old man died of electrocution on a waterlogged road. Now HYDRAA is pitching itself as the solution — a model that could be replicated in Bengaluru, Mumbai, Gurugram and beyond.

So far, there have been encouraging results in some pockets of Hyderabad.

Dhanapalan has moved back into her Paigah Colony home. This year, even with desilting still underway, she says her house didn’t flood. At the core of her colony’s waterlogging issue was a stream called the Patny nala in Hyderabad’s twin city Secunderabad.

A five-storey building and other encroachments had come up on the stream, leading to flooding in 27 colonies. For 30 years, no government agency took action to resolve the encroachment. HYDRAA cleared it in three months.

For the city, HYDRAA is now part of common parlance. During monsoons, citizens receive daily rainfall alerts on their phones, accompanied by words of caution. News channels constantly cover HYDRAA demolitions and lake rejuvenations.

“Seeing a HYDRAA car is a bit intimidating now,” said an IT professional who didn’t want to be named. “You may not even know your house is on lake land, and HYDRAA will come and demolish it without notice. It has caused fear in the right quarters but also paranoia among common citizens.”

Even as critics excoriate HYDRAA for use of excessive force, the state government remains defiant, dismissing the backlash as politically motivated “slander”.

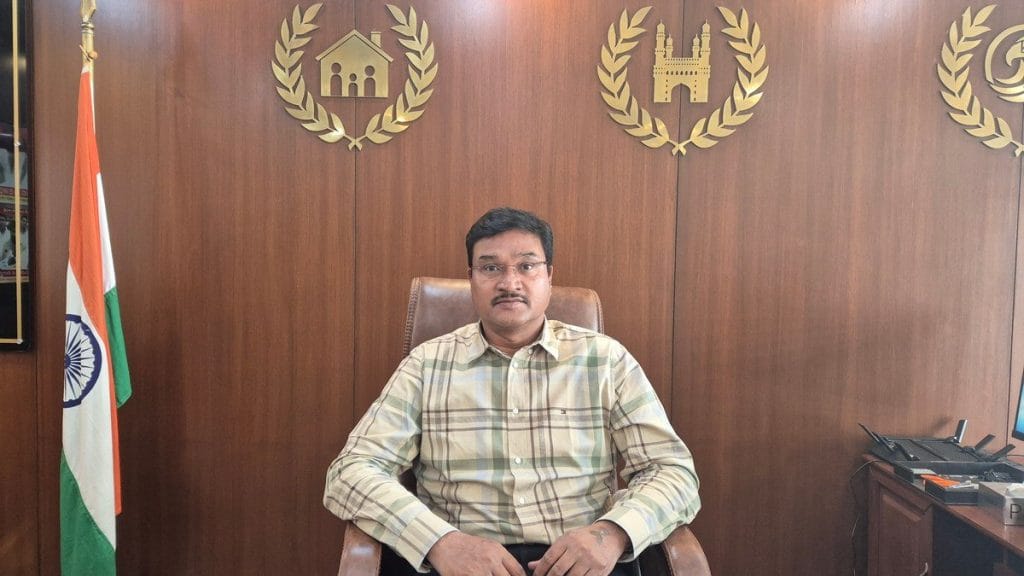

“Powerful people control the media and ran a campaign against it,” said HYDRAA commissioner AV Ranganath. “But people have seen our good work, and we enjoy support in the city.”

More pushback, more power

Every Monday, IPS officer AV Ranganath arrives early at his office to deal with the day’s queue. Starting at 6 am, residents begin lining up with their complaints of waterlogging and encroachments. This is part of HYDRAA’s weekly Prajavani, a forum where people can directly voice their concerns to the commissioner and get issues resolved.

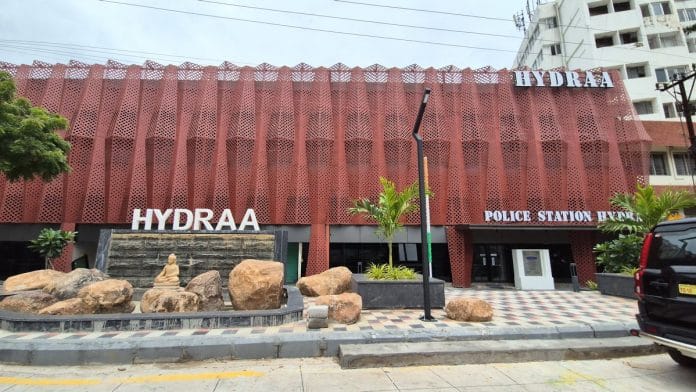

Just outside the office stands a sleek new HYDRAA police station, which is soon to be inaugurated. It’s billed as the first in the country dedicated to environmental crimes, including encroachments on lakes, forests, and drains.

“Illegal land grabbing and construction on lake land will be thoroughly investigated. The SHO leading the station will hold the rank of ACP. We are committed to delivering environmental justice,” Ranganath said.

Since its formation, HYDRAA has steadily gained teeth.

“Initially, we faced resistance and even received legal notices, but the government recognised the need to empower us,” Ranganath said from his office overlooking Hussain Sagar lake. On 16 October 2024, an amendment to the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) Act gave HYDRAA sweeping powers to seize government and public lands.

The amendment states: “HYDRAA is hereby empowered to protect public assets such as roads, drains, streets, water bodies, open spaces, and parks within the jurisdiction of GHMC or the State Government, to guard against illegal encroachments for disaster management and preservation of public property.”

My father had bought that land from a private seller in 2014, after selling off his land in the village. We had all legal permissions and GHMC-approved plans. HYDRA created an issue here when there was none

Nunna Neeraj, Hyderabad resident whose new house was demolished by HYDRAA

HYDRAA’s ‘bulldozer raj’ has not been limited to the poor residing in slums. To make a strong statement, the agency has even torn down villas and complexes. Its actions — including seizing land from elected representatives and demolishing Telugu star Nagarjuna’s convention centre — have attracted national attention. It’s also led to a litany of court cases. The agency already faces more than 200 cases, all for one year’s work.

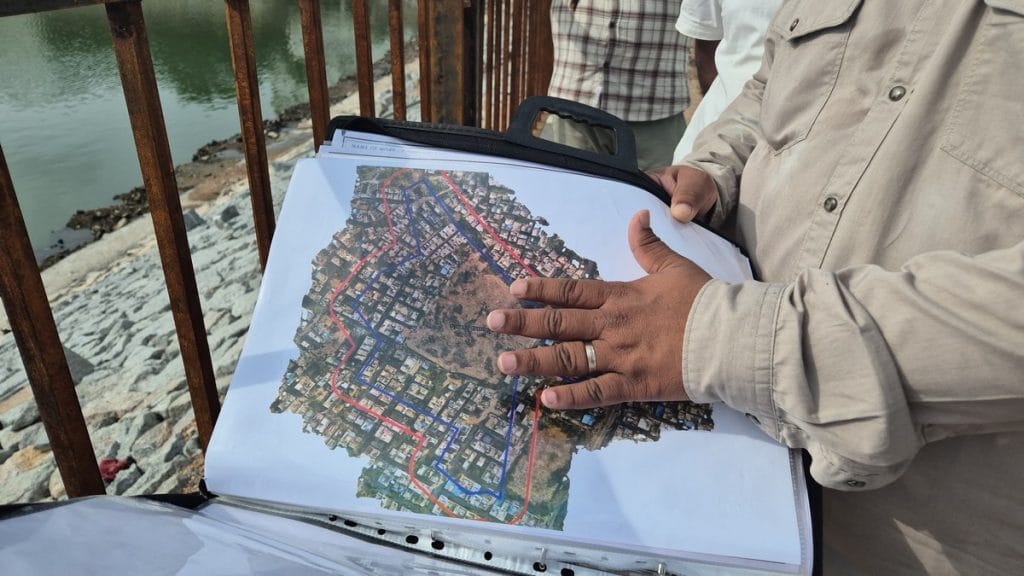

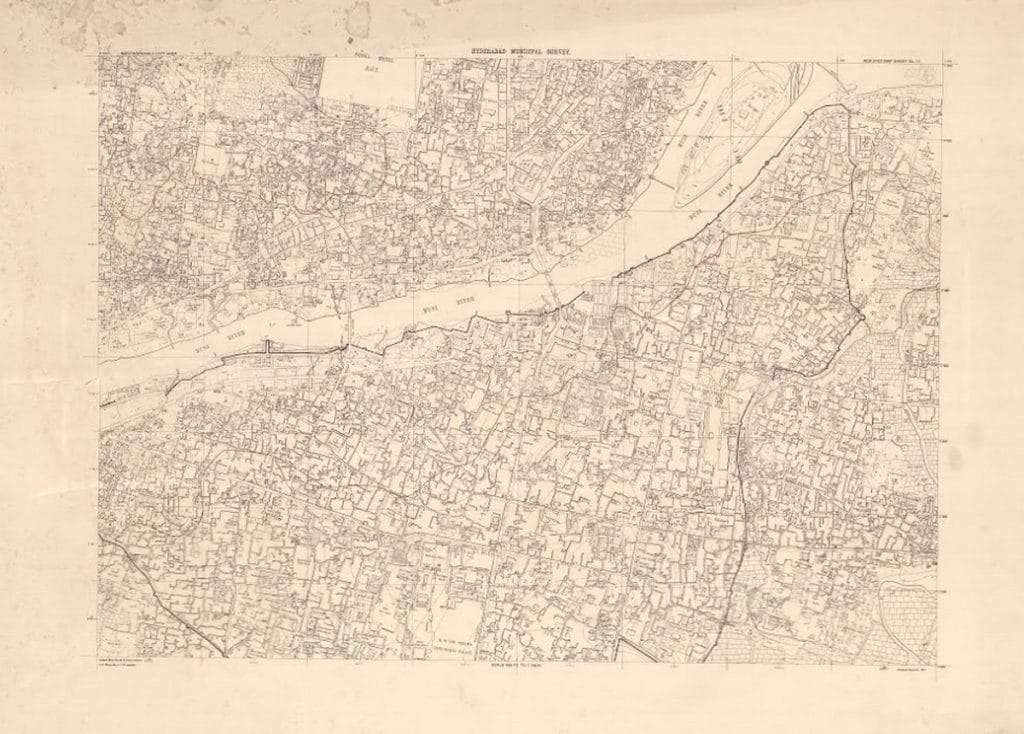

Much of HYDRAA’s focus is on the Full Tank Area of lakes, where Survey of India maps and Nizam-era municipal records are being used to identify lost catchments.

“One week after assuming charge, I visited the Remote Sensing Agency under ISRO,” Ranganath recounted. “They presented alarming data showing that 61 per cent of Hyderabad’s water bodies have vanished. They warned if encroachments aren’t curbed, all could disappear within 15 years. That was the wake-up call for us.”

Back in 2020, viral videos showed boats being used to rescue residents trapped by floods in Hyderabad’s colonies. Ranganath argued these areas are actually encroached lake beds where water naturally accumulates during rains. This year too, Hyderabad has suffered torrential rains, with even flyovers getting flooded. For a city that ranks high on lifestyle indexes and wants to position itself as the new Bengaluru, repeated urban floods are a serious dent on its investment worthiness.

“Hyderabad is an urban heat island, due to which erratic storms and heavy downpours are becoming increasingly common,” said ecologist Arun Vasireddy, a research scholar at the University of Utah.

Rebirth of lakes

To show what that future could look like, Ranganath pointed to Golusu Kattu, a chain of interconnected lakes that HYDRAA aims to reclaim. The plan is to restore the entire network of streams and drainage channels to help carry stormwater.

HYDRAA, however, is not Hyderabad’s first revival mission for heritage water systems. In 2015, the state launched Mission Kakatiya to restore 45,000 tanks across Telangana; the ongoing project was named in tribute to the Kakatiya dynasty that built many of them. Two years before this, in 2013, Hyderabad activists started the Save Our Urban Lakes campaign, urging citizens to save disappearing lakes. HYDRAA has picked up that thread, though at a far more aggressive pace.

The agency has engaged consultants from a Bengaluru civil engineering firm, Vimos Technocrats, for the revival project. Among the major lakes being restored is Bathukamma Kunta, two kilometres from the Musi river. Once largely reduced to a landfill, a section of it is now filled with water. Around it, tracks are being laid and a gazebo constructed for people to enjoy.

On a rainy afternoon, Younus Pervez, managing director of Vimos Technocrats, was deep in discussions with government inspectors as bulldozers scraped silt off the lake’s banks.

“The drain to the lake was completely blocked. This was leading to flooding in the colonies around it. We installed a box drain for rainwater to come here. The water won’t be stagnant; it will be connected to another drain which will take the water to the river,” said Pervez, whose firm is working with HYDRAA on the site at a cost of Rs 8 crore.

The original lake, according to records, was 12 acres wide. The reclaimed area is only about five acres.

“Bathukamma Kunta is among the six lakes that HYDRAA is reviving. The land has been grabbed by a local politician. It is Rs 300-400 crore worth of government property which we have reclaimed,” Ranganath said.

By his count, HYDRAA has reclaimed Rs 15,000 crore worth of encroached government land over the past year.

A city’s flood trauma

The water receded more than a century ago, but the story of its fury is still not forgotten. On 28 September 1908, a cyclone in the Bay of Bengal triggered flash floods in Hyderabad. Around 15,000 people died in a single day and lakhs were displaced, according to Mohammed Safiullah, trustee of the Deccan Heritage Trust.

The disaster prompted the Nizam, Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, to overhaul the city’s flood management infrastructure. He brought in famed engineer Mokshagundam Vishvesvaraya, later awarded the Bharat Ratna, to design a system.

In his memoir, Vishvesvaraya recorded that Hyderabad received 18.90 inches of rain in 48 hours, with water levels on the Musi river rising from 110,000 cusecs to 425,000 cusecs. Of the 788 tanks connected to the river, 221 were breached.

Vishvesvaraya began work on 15 April 1909, proposing both a modern drainage system and flood-protection reservoirs. The reservoirs were quickly approved and eventually became Osman Sagar on the Musi and Himayat Sagar on the Esi, which are popular picnic spots to this day.

Next came the drains. During his visits, Vishvesvaraya observed that almost every house had an open tank in front, often turning into mosquito-breeding grounds.

“The more important work that was first undertaken was the diversion of city sewage from both banks of the river through pipe ducts into a separate sewage farm. A site was selected for the farm on the left bank of the river and to the east of the city. The sewage from the south bank of the river was taken by a pipe across the river below the Chadarghat Bridge and conveyed to the farm mentioned in an earthen channel along with the sewage from the left bank,” the engineer wrote in his memoir.

He would return to Hyderabad at least six times in the 1920s to oversee the work on the drains.

“Special attention was paid to the development of district or street sewers and house connections,” he noted.

Originally, the indigenous rulers—the Kakatiyas, the Qutub Shahis, and the Asif Jais, in that chronology—realised this is a rainfall-deficient area with no major rivers nearby except the Musi, which is rain-fed. So, as early as the 1550s, there was a need to excavate old Kakatiya lakes

-Mohammed Safiullah, trustee of the Deccan Heritage Trust

Some of Vishvesvaraya’s efforts have stood the test of time. The core of Hyderabad has not flooded much since then, argued P Anuradha, president of INTACH’s Hyderabad chapter.

“Water near Charminar never stays; it disappears quickly. But encroachments now have started leading to floods there as well.”

But long before Vishvesvaraya, the city had relied on tanks and lakes built under earlier dynasties.

Safiullah said that successive rulers of Hyderabad through the centuries saw the importance of reviving lakes.

“Originally, the indigenous rulers—the Kakatiyas, the Qutub Shahis, and the Asif Jais, in that chronology—realised this is a rainfall-deficient area with no major rivers nearby except the Musi, which is rain-fed. So, as early as the 1550s, there was a need to excavate old Kakatiya lakes,” he added.

Hyderabad once had close to 900 lakes, by his estimate, most of which have been lost. These are among the water bodies and nala systems that HYDRAA now seeks to resurrect.

Lives uprooted

Nunna Neeraj had spent ten years building his house. Just as his family was preparing to move in, he got a call that upended everything. His new abode had been reduced to rubble. HYDRA said his and 50 other houses were in the full tank area of a lake, Sunnam Cheruvu.

“My father had bought that land from a private seller in 2014, after selling off his land in the village. We had all legal permissions and GHMC-approved plans. HYDRA created an issue here when there was none,” Neeraj alleged.

The dispute over Sunnam Cheruvu is long-standing. Residents insist their houses lie north of the lake. But a 2016 GHMC resurvey mapped their plots inside the full tank area. Survey of India topo maps had earlier measured Sunnam lake at 26 acres. GHMC revised this to 32 acres. HYDRAA argued that while permission was granted for only 65 villas in the Madhapur area, 255 had come up.

High drama ensued last year when the structures were demolished. A couple even doused themselves in diesel.

Residents claim they have complete land records.

“We are facing systematic abuse. We are continuing to fight with HYDRAA,” Neeraj said. “This land belonged to a Britisher, later passed down to a former chief justice of united Andhra Pradesh. This land is on higher ground. Even in very heavy rains, not even a drop of water stays here because this is all upland with rocks and boulders.”

HYDRAA has since cleared the lake bed and is rejuvenating the water body. It has also cracked down on local water mafia that was extracting and distributing polluted lake water. Tracks and an open gym have come up in the area, much as has been done at Bathukamma Kunta.

What happened at Sunnam lake has played out along other lakes too, and not always by HYDRAA. Across Hyderabad, restoration projects around the Musi and other lakes threaten to displace thousands.

At Chadar Ghat, debris from 250 demolitions already litters the riverbank. These have been removed by the Musi River Development Project, a multi crore dream project of the government to rid Musi of encroachments. Residents of Shankar Nagar, who say their families have lived there for more than 70 years, refuse eviction unless given new housing nearby.

Where are we going to go? In the jungle? We work here, we want to be relocated nearby, in the city. Demolish the race club and give it to us

-Sheikh Nizam, resident of Shankar Nagar

“Thousands more houses will be demolished. The river will not get its way though. Malls and houses for the rich will be made,” alleged M Adnan, a city executive member of the Communist Party of India. “Why do they have to develop touristy places in the houses of the poor? Relocation is fine; the houses are good, but they should be given nearby.”

Residents have been living in fear of the next bulldozer. Sheikh Nizam, a resident of Shankar Nagar, said he was born here and had not moved since.

“Where are we going to go? In the jungle? We work here, we want to be relocated nearby, in the city. Demolish the race club and give it to us,” he said, overcome by emotion.

Ranganath acknowledged the displacements but defended the approach. For him, it’s a question of the city’s survival.

“Even though these are illegal encroachments in buffer zones, we are offering rehabilitation to all; we have made arrangements for it,” he said.

Also Read: Rise and fall of India’s BRTS. ‘World-class’ solution that made problems worse

Bulldozing through criticism

Congress worker Lubna Sarwath fought for the revival of Bathukamma Kunta as part of Save Our Urban Lakes. But she’s no fan of HYDRAA. She’s angry at its “unscientific” approach, the lack of public consultation, and even the involvement of a Bengaluru-based engineering company.

“What is Bangalore doing here? In Telangana, we have all the expertise; retired engineers are willing to volunteer. Youth are volunteering; we have designs and plans. Why haven’t you tapped into it? Who has designed it, and why does a lake need a huge gate?” she asked.

Sarwath said HYDRAA was meant to restore the Hyderabad’s ecology, but poor planning and needless concretisation in lake beds are undermining that goal.

The lakes have to be restored scientifically or there’s no point in doing it, but even academics haven’t been contacted by HYDRAA

-Arun Vasireddy, ecologist

“What the lake needs is dynamic restoration. Every water body has buffer zones, even beyond the full tank level, where the gradient gets sunk into the ground and flows into gravity-based channels. Now the lake is being concretised, with box drains in the channels. Imagine… they are harming the lake’s natural dynamicity,” she added.

Other heritage experts also said that the agency should have sought greater participation from Hyderabad’s citizens and scholars for the lake restoration.

“I have studied lakes in depth and know the environmental concerns regarding them. The lakes have to be restored scientifically or there’s no point in doing it, but even academics haven’t been contacted by HYDRAA,” Vasireddy said.

But Bengaluru’s Vimos Technocrats argues that their track record is proof of their competence.

“We have worked to revive 126 lakes in Bangalore; we know what we’re working with,” managing director Pervez said.

He added that the lake’s “dynamicity” would be maintained and that a channel linking Bathukamma Kunta to the Musi had been mapped out.

HYDRAA chief Ranganath, however, is a bulwark against criticism. Heading a 2,200-strong force, he is always ready with Supreme Court and government orders to justify HYDRAA’s work. He insists that enough environmentalists and scientists have been consulted for the agency’s projects.

With maps pasted on the walls of his office and an eye on the four television screens running constant news, he is barrelling ahead, convinced that other cities will follow HYDRAA’s lead as well.

“Our work will be seen as a model by other cities like Gurugram, Mumbai, and Bangalore—to save their heritage systems and water bodies and escape the curse of flooding,” he said.

This article is part of Urban Pressure, a series on how bad planning is choking Indian cities.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)