New Delhi: Within months of getting his law degree, Muslim lawyer Kayum Khan was thrust into the biggest case of his career. Except, he was the accused, fighting POCSO charges for assaulting a minor. But his real crime was marrying a Hindu woman.

“I studied law to bring change. I never anticipated that it would be used against me. I’ve learnt to despise the same system after experiencing it firsthand,” said Khan, who lives on the outskirts of Jaipur.

On 11 June 2019, the newly-minted lawyer— he was 28 at the time—was on his way to work when he was arrested for sexually assaulting his girlfriend’s minor sister.

“My girlfriend’s aunt, Indra Devi, first questioned me about how I was brainwashing Shweta, my girlfriend. Then, out of nowhere, the younger sister emerged and started yelling. She shouted that I had groped her,” said Khan.

When he and his Hindu Jat neighbour Shweta Choudhary decided to get married in 2019, the term ‘Love Jihad’ had become part of the local lexicon. But what neither of them anticipated was how even applying for a secular court marriage licence would turn the legal system against them.

The scourge of so-called honour killings that swept states such as Haryana, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu over inter-caste marriages through the 2000s has taken on a new, intolerant avatar—Hindu-Muslim marriages. Except now, it isn’t killing but the weaponisation of laws. Across India, inter-religious, inter-caste, and queer-identifying couples have faced rape, POCSO, kidnapping, and even theft charges as a means to stop their relationships—often with sanction from police and state authorities.

“Criminal law is used to criminalise adolescent sexuality,” said lawyer and researcher Neetika Vishwanath.

Research, news reports, and court records reveal a clear pattern: when couples cross caste or religion boundaries to find love or elope, their own families often file criminal complaints. Consensual partners become kidnappers and rapists. And laws meant to protect women are being subverted to target them.

The local Bajrang Dal and VHP men were alerted by our own lawyer—a man we thought was helping us! They stopped us from getting married, and later got me arrested saying I was coercing my partner who was underage. I spent more than four months in jail, the bail came through in October that year

-Shaban, who finally married his Hindu girlfriend a year after eloping

“Once the police act on the complaint and hunt down the couple, the man is taken into custody and the woman’s family is given access to her irrespective of her consent. This allows the family to intimidate and pressurise the woman to indict the man before her police statement is recorded,” Vishwanath wrote in her 2015 study of rape trials in Lucknow. She found that 52 out of the 95 trials—54.7 percent— observed in a Lucknow fast-track court involved runaway marriages.

A decade later, the situation has not improved.

“The increased age of consent from 16 to 18 years since the POCSO Act coming into force in 2012 further compounds this issue,” she added.

Today, more than a dozen states have enacted anti-conversion laws that embolden vigilantism and state interference in personal relationships. But older criminal laws are still routinely being used against Indians rebelling against social boundaries, falling in love, and exercising their autonomy.

In a report published in March 2025, JNU doctoral scholar Swapnil Singh analysed nearly 50 judgments by the Allahabad High Court and found that in most cases involving inter-faith and inter-caste couples, authorities invoked sections on abduction and kidnapping.

“When I started my research, I was looking at the impact of anti-conversion laws on couples but I found that the State always had mechanisms to intervene and stop such relationships even before,” said Singh.

“The cases would also use the language of ‘seduction’ while trying to make a case of kidnapping or abduction, as if these women were being lured or seduced against their will, into eloping with the man.”

Also Read: Rationalists look for love in new India. Kerala’s Secular Matrimony swipes left on religion

Neighbours to lovers to suspects

Khan never set out to ‘seduce’ Shweta Choudhary with malicious intent. Having grown up as neighbours in the industrial locality of Vishwakarma, they were friends for several years before they started dating in 2016. She was curious about how Muslims were portrayed on TV news debates. Especially their religious practices and stories about ‘triple talaq’ and ‘jihad’, he recalled with a grin.

“There was no love-shove back then, but gradually we got to know each other. I loved spending time with her. And at some point, we both knew marriage was the inevitable step,” said Khan.

But when Choudhary’s family found out about her relationship with their Muslim neighbour in 2019, they were furious. They were trying to get her married to a man within their Jat caste. It became so bad that on 7 June that year, she fled and took refuge at Shakti Stambh, a Rajasthan University-led home for women in distress.

Couples are hunted down and the women are sent for medical examination. The observation in the medico-legal certificate about the status of women’s hymen as torn becomes an evidence of sexual intercourse and thereby, statutory rape

-Neetika Vishwanath, lawyer and researcher

Four days later, on 11 June, Khan was accosted by her family. What followed was a series of events culminating in his imprisonment on charges of sexual assault. The police registered an FIR against him for allegedly molesting Choudhary’s 17-year-old sister. Khan spent 40 days in jail, and when he finally got bail, he found Choudhary holed up at the Shakti Stambh.

“I didn’t even know that Kayumji was in prison ever since I left home. On multiple occasions, media and local members of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad kept hounding me. Some VHP people came and told me that he will force me into wearing a burkha, eating meat. I told them that even members of my family eat meat,” Choudhary said wryly, fidgeting with the corner of her yellow kurta.

The couple eventually got married in November 2019, despite threats from Choudhary’s family. Six years later, Choudhary is pregnant with their second child, and Khan continues to fight the case and the POSCO charges.

In their one-bedroom home in a Muslim-majority neighbourhood in Jaipur, Khan and Choudhary rifle through a sheaf of application forms for grade three and four government jobs. So far, the search has been futile. To make ends meet, they run a small documentation and xerox centre, as Khan—tainted by the criminal charges against him—struggles to find clients.

Before his own ordeal, Khan had already seen the upheaval that an interfaith marriage could trigger. Six years ago, his younger brother married his college girlfriend—a Hindu woman. After her parents found out, they beat her up and allegedly tried to send goons affiliated with the Bajrang Dal to the Khan household. But the girlfriend escaped to a Shakti Stambh shelter. They approached the police and finally got married under the Special Marriage Act in May 2019.

“The difference is that her family were Sainis and eventually came around to her decision. My brother was also threatened, but he wasn’t booked under a false case. I was also beaten up by her family, but that matter never reached the court for trial,” Khan said.

Uttarakhand has seen an almost fourfold increase in the number of POCSO cases between 2016 and 2023. Data analysed in Dehradun district between 2015 and 2023 also revealed that in each year, at least one in four POCSO accused was Muslim.

From consent to criminal charges

Five hundred kilometres away in Dehradun, 24-year-old automobile repair mechanic Shaban has been living a similar nightmare. Labelled a child abuser, he and his Hindu partner still live in fear of vigilantes.

Uttarakhand has the Himalayas, Char Dham, and now the Uniform Civil Code. Couples living together must register with the authorities, provide personal details, and get the approval of parental guardians and religious or community heads.

According to a Scroll analysis, the state has seen an almost fourfold increase in the number of POCSO cases between 2016 and 2023. Data analysed in Dehradun district between 2015 and 2023 also revealed that in each year, at least one in four POCSO accused was Muslim.

More often than not, the police play an active role, even suggesting to aggrieved family members what they can do, according to Vishwanath.

“My research on rape trials in Lucknow corresponded to this category of cases. They mark a collusion of the familial and legal forces who characterise these instances as shaadi ka jhaansa (trap of marriage),” she said.

Criminal law is activated against the male partner after the family claims their daughter is below the age of consent. What usually begins as a missing person or kidnapping complaint is later converted into charges of kidnapping and rape, she added.

“Couples are hunted down and the women are sent for medical examination. The observation in the medico-legal certificate about the status of women’s hymen as torn becomes an evidence of sexual intercourse and thereby, statutory rape.”

In May 2023, Shaban and his Hindu girlfriend, a neighbour, decided to marry. He was 21, she 18—both legally adults—but they had been in a relationship for over a year and a half, including a period when she was still a minor. The two eventually decided to elope under the Special Marriage Act (SMA) and submitted their documents for marriage at the registrar’s office in the Vikas Nagar locality. Trouble began immediately.

“The local Bajrang Dal and Vishwa Hindu Parishad men were alerted by our own lawyer—a man we thought was helping us! They stopped us from getting married, and later got me arrested saying I was coercing my partner who was underage. I spent more than four months in jail, the bail came through in October that year,” said a weary Shaban.

The moment you’re able to put in a complaint of ‘missing’, abduction, kidnapping, or even sexual assault and rape, the girl has to give a statement before the police or magistrate. It allows her to be produced before cops, who often coerce her into going back to her parents

-Kavita Srivastava, head of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL)

The police investigation and the medical reports found no evidence of assault as listed under POCSO. The young woman too in her statement to the magistrate was in her lover’s favour. The relationship was consensual.

After he made bail in October 2023, the couple reunited but initially decided against marriage.

“We knew the clock was ticking, because of the new laws regarding registration of live-in relationships here in the state. We were being cornered from all sides with these laws,” said Shaban. Eventually, though, they approached the high court bench in Nainital and got their marriage registered in May 2024.

Such stories are repeating themselves with depressing regularity across India. Just last month, 29-year-old Akbar Khan was arrested in Ghaziabad after the father of his wife, Sonika Chauhan, filed a kidnapping complaint. The couple had married under the Special Marriage Act in 2022 and had been living together in Indirapuram ever since. But when Sonika’s family recently discovered the marriage, they went to the police. Though both were consenting adults, the police registered a case under the Bharatiya Nyay Sanhita. Akbar was jailed. Sonika was forced to return to her family.

Data from even a decade ago points to a pattern that has only intensified. In 2014, The Hindu investigated over 600 judgements from Delhi’s district courts pertaining to rape and sexual assault. This was a year after the Nirbhaya or Delhi gangrape case, in the backdrop of growing conversations on India’s omnipresent rape culture.

An analysis of these cases revealed that a fifth of the trials ended because the complainant did not appear or turned hostile. More importantly, of the 460 cases that went to full trial and pertained to sexual assault, 174—more than a third—involved runaway young couples who were in love or seeking to elope. This was especially true for intercaste and interfaith couples.

Similar findings were reiterated in lawyer and researcher Neetika Vishwanath’s study of rape trials in Lucknow.

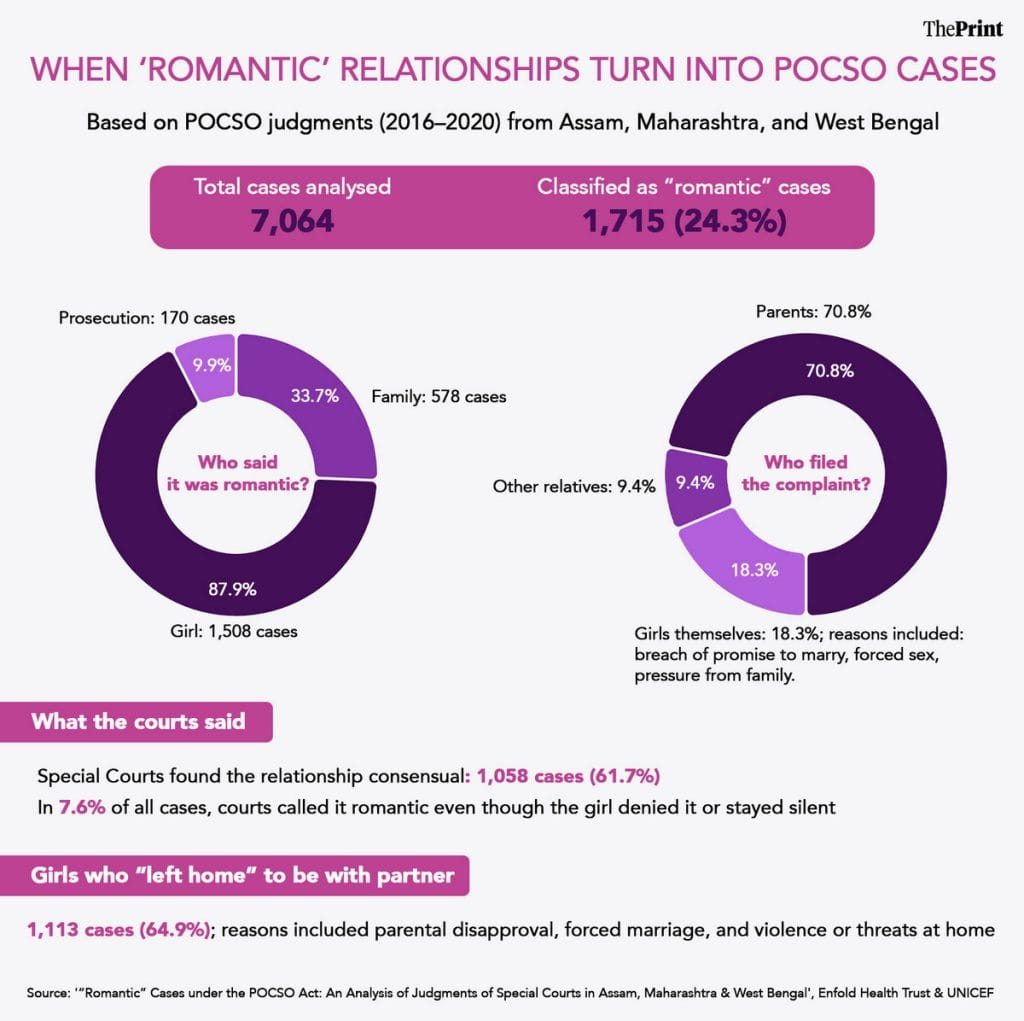

A more recent 2022 study commissioned by the NGO Enfold Health Trust in collaboration with the UNICEF found that of the total 7,064 POCSO judgments registered between 2016 and 2020 and available on e-courts from Assam, Maharashtra, and West Bengal, at least 1,715 in fact constituted “romantic” cases and most complainants were parents.

“The moment you’re able to put in a complaint of ‘missing’, abduction, kidnapping, or even sexual assault and rape, the girl has to give a statement before the police or magistrate. It allows her to be produced before cops, who often coerce her into going back to her parents,” said Kavita Srivastava, a Jaipur-based civil rights activist and head of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL).

Lawyer Neetika Vishwanath said her research on rape trials in a Lucknow court showed over 54.7 percent involved runaway marriages. “They mark a collusion of the familial and legal forces who characterise these instances as shaadi ka jhaansa (trap of marriage),” she said.

When daughters become thieves

For Pooja, 23, and Farooq, 27, the risk of elopement and their flight from Rajasthan’s Hanumangarh to Delhi’s Mayur Vihar came with an added tag they didn’t bargain for: theft. Her family accused them of stealing Rs 11 lakh and three kilos of gold and silver jewellery.

“Look at this house, what part of it looks like we had any such money or belongings?” said Pooja, between sips of water, as she gazed around their one-BHK flat in a crowded neighbourhood near the Delhi-Noida border.

The Bachelor of Science graduate first met Farooq on a local bus while on her way to college. When Farooq told a friend of hers that he liked her, they exchanged numbers.

“I first told him, why do you want my number? You already have a lot of girls’ numbers, no, to flirt with? But then I realised he was genuinely interested, and we started talking,” said Pooja.

By 2021, when she was in her final year of college, her parents found out about the relationship and immediately arranged for her to marry a man from the same caste.

“That’s when I knew I had to leave from there. Farooq was also facing pressure from his family too. So on the pretext of getting my marksheet I ran to the Mahila Suraksha Salah Kendra, and from there we escaped to Delhi,” said Pooja.

They arrived in the capital with all their possessions and documents stuffed into two bags, and Rs 2,000 in hand—only to learn that Pooja’s parents had filed a case of theft against them.

This isn’t uncommon. “If the woman runs away from home, they try to accuse such eloping couples of stealing the family’s belongings,” said Srivastava, who is currently working on a case involving an interfaith couple from Bhopal. There too, the woman’s family accused the couple of theft in an attempt to bring her back.

Pooja alleged that her paternal uncle, a retired circle inspector, used his connections to get an FIR registered against them.

“My bank account was also frozen. We had to file a petition at the high court at Jodhpur, to quash this FIR against us,” she said.

Nobody from either of our families came for the delivery of our first daughter. But my family did show up at every court date for their case against my husband

-Shweta Choudhary , who married lawyer Kayum Khan

With the threat of arrest hanging over them, the couple struggled to get jobs and find a place to rent.

“The accusation of being thieves still stopped us from renting a place to stay, as if it wasn’t already hard for us as a Hindu-Muslim couple,” said Farooq tersely.

Desperate Google searches led to dead ends. Groups like Love Commandos were no longer active. Eventually, they found an NGO called Dhanak, an initiative run by interfaith couple Asif Iqbal and Ranu Kulshrestha, which helped them with legal aid and organised a temporary safe home.

In July 2021, the two finally got married under the Special Marriage Act, after waiting over four months for their documentation to be approved by the sub-divisional magistrate at Mayur Vihar. Today, while Pooja is filling in applications for nursing vacancies, Farooq works as a loan refund agent at a bank, earning Rs 20,000 a month. A large chunk of that goes toward rent.

The FIR accusing them of theft has now been quashed, but their fears persist. Pooja’s family remains opposed to their union.

In Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan, another pair of star-crossed lovers faced a similar harrowing experience. Back in 2016, the teenage couple took shelter in a remote village in Tripura but it was only three years later that the CBI absolved the young man of kidnapping. Investigators also found that the girl’s parents had wrongly accused their daughter of stealing Rs 70,000.

In her book Public Secrets of the Law: Rape Trials in India, scholar Pratiksha Baxi also showed how criminal laws—from rape and POCSO to kidnapping and abduction—were frequently invoked under the guise of protecting young women who chose to elope or marry against their family’s wishes. Her investigation, which was limited to Gujarat, also found that theft charges were often brought against women who fled home for love.

Also Read: Arya Samaj weddings are in trouble. Courts cracking down on certificates, conversions

‘Her family killed her’

Khan and Choudhary, Pooja and Farooq, and Shaban and his partner are battered and bruised, but not broken. All count themselves fortunate—they are still alive.

Not a day goes by when Roshan Mahawar from Dausa district in Rajasthan doesn’t think of the woman he loved—Pinky Saini. In 2021, when he was 23 and she 19, they decided to elope. Theirs was a young love that bloomed while Saini was in inter-college (high school) and grew over furtive meetings at a small shop in Jabras village where they lived.

But the two belonged to different castes: Pinky was from the Saini (OBC) caste, and Mahawar was a Dalit. As word got out, disapproval turned into outright hostility. And a familiar pattern played out. Saini’s father, Shankar Lal, arranged for her to be married in February 2021. She fled with Mahawar. Her family said she had been kidnapped and the police jumped to file the FIR.

“They claimed I threatened her and put a gun to her head,” said Mahawar.

But the couple made one misstep. Unlike the others who built their lives far from their families, Saini and Mahawar returned to Dausa after they were legally married. They had already approached the Jaipur Bench of the Rajasthan High Court, seeking protection from her family. The court directed the police to give them protection, but they were slow to act and did not accompany the couple when they returned to Dausa.

Just days later, Saini was kidnapped from the Mahawars’ family home. Her dead body was discovered shortly thereafter.

“It was her father who arranged to kidnap her and kill her. But that case isn’t moving forward or seeing any justice,” said Roshan Mahawar, speaking to ThePrint over the phone. Her father Shankar Lal confessed to strangling her.

“The police did not act in time. Her family killed her. It’s been more than four years since then, and even today the correct identification of her kidnappers hasn’t happened. Their lawyers are also of the same caste as them. I’ve given up and lost all hope,” said Mahawar.

Back in Jaipur, Shweta Choudhary’s face glistens with sweat and worry as she tracks the progress of the POCSO case against her husband. The matter is now posted for final arguments, and the couple hopes to see the end of it before their baby is born.

“Nobody from either of our families came for the delivery of our first daughter. But my family did show up at every court date for their case against my husband,” she said

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

I don’t condone lying but until we have stringent laws to curb love jihad before the damage is done (most existing laws only come into play after the worst has happened), it is a palatable ‘second best’ option.

I am wondering why such couples often consists of muslim men and hindu women, with the women converting to Islam post marriage,

Can Ms. Sabah Gurmat explain why in every single instance listed out in this article, the male is Muslim while the female is Hindu?

Why is it that Muslim men seem to be always on the lookout for a Hindu partner?

There is not even a single instance in this article of a Hindu man being in a relationship with a Muslim woman? Why is it so and what does it tell us?

Isn’t it quite obvious from this article itself that there is a clear pattern to “interfaith relationships”. It’s always a Muslim man “falling in love” with a Hindu/Sikh/Christian woman. The reverse hardly ever happens. Why is that so, Ms. Gurmat? Care to explain?

Why is the article only about Muslim men marrying Hindu woman ..? Hope we will read about the other side Hindu men marrying muslim woman