Hisar: Sunil Krantikari sells FASTag at the Landhari toll plaza in Haryana’s Hisar. But traffic is not all that he is monitoring. He is keeping an eye on the movement of cows on the highway. He is a secret gau rakshak under the garb of a toll plaza salesman.

He really comes into his own after dark, when he transforms into a protector of cows. Except the cape, everything else is in place in his double life. The toll plaza is his command-and-control centre. From there, he tracks each and every vehicle and can quickly access information about the owner’s name, vehicle number, address, and routes. If he suspects a vehicle is trafficking cows, he immediately alerts his fellow gau rakshaks stationed at other tolls.

“Since I am a private agent who applies FASTag near toll plazas, I get all the details of the vehicles, their destination, and the owner’s name, which I forward to my team,” said 29-year-old Sunil, who’s been working here since 2021.

He insists, earnestly, that he’s taken up the job not for the money—just about Rs 3,000 a month—but to track vehicles suspected of smuggling cows. Sunil is part of a vast network of largely jobless but passionate gau (cow) influencers in Haryana. These vigilantes regularly update their operations on Instagram, rally fellow cow enthusiasts to join, and post religious songs with messages like “Wake Up Hindus”.

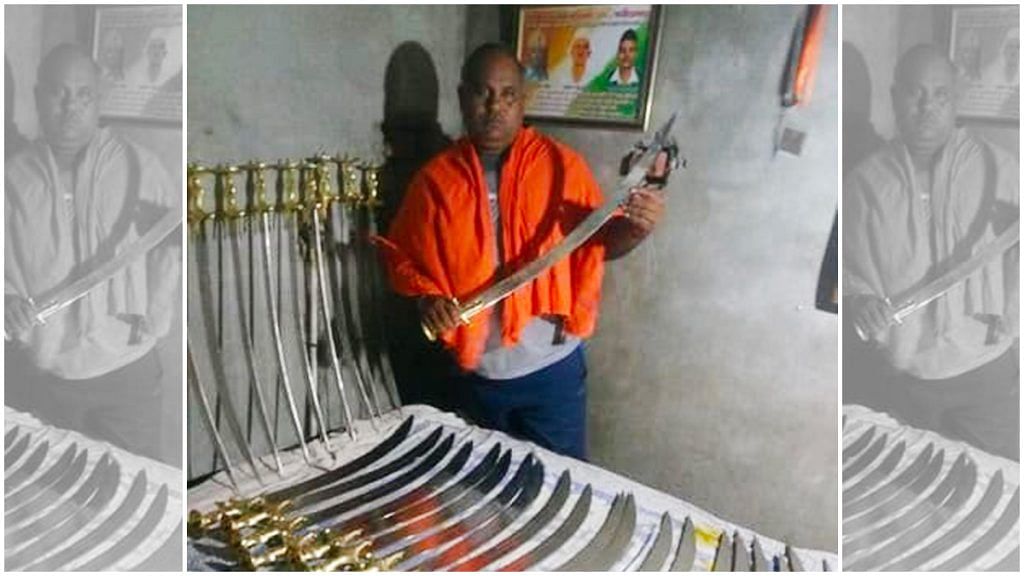

Cow vigilantism works like a well-oiled machine in Haryana, which has become a hotbed of anti-Muslim hate. The state’s 2015 cow protection law has produced a new breed of gau raksha influencers in the NCR — from Monu Manesar to Bittu Bajrangi and Rocky Rana.

They aspire to a lifestyle involving bouncers, guns, and SUVs—symbols of their muscular brand of Hinduism. Sunil proudly claims to have coordinated with murder-accused Monu Manesar whenever a vehicle crossed Hisar. He describes Monu’s arrest last September as a failure of the administration. He argues that gau rakshaks have to take on the task themselves because the police just don’t respond with the same speed.

The Cow Protection Task Force was meant to be a police-public mission to protect cows. However, the gau rakshaks got an unofficial sanction through the task force, and now they have grown so powerful that the state is unable to control them

Former Haryana ADGP

Haryana is now helplessly tangled in a web of its own creation. It’s caught between a largely indifferent police, Hindutva ideology, and a mushrooming freelance industry of aggressive vigilante groups. On the highways, these gau rakshaks act more like gangs—running a tight network of informers, engaging in reckless high-speed chases, and often extorting money, all under the guise of religious duty. In just the last two weeks, two people have been killed—a Muslim labourer in Charkhi Dadri, and a Hindu teenager in Faridabad in a case of ‘mistaken identity’—under the pretext of “protecting cows.” Now, with the violence escalating, the state is scrambling to regain control.

What sets Haryana apart is that the state’s policies have only emboldened this volatile vigilantism. Many gau rakshaks claim to be associated with the Cow Protection Task Force, notified by the state government in 2021 to prevent cow smuggling and slaughter, rehabilitate stray cattle, and assist law enforcement. Teams of eleven members were created in each district to collect information and inform the police.

But with the task force largely defunct, an army of self-appointed gau rakshaks has taken over. They set up checkpoints, stop vehicles, chase suspects, and, in some cases, hand down their own brand of “justice”. And they blame the police and administration for having a lackadaisical approach toward cow protection.

Cow vigilantism is “ideological, commercial, and symbolic”, according to a former Haryana additional director general of police (ADGP), asking not to be named.

“The Cow Protection Task Force was meant to be a police-public mission to protect cows. However, the gau rakshaks got an unofficial sanction through the task force, and now they have grown so powerful that the state is unable to control them,” said the ex-ADGP, a former member of the Haryana government’s Gau Seva Aayog, which oversees cow welfare in the state.

The officer added that the administration initially prioritised cow welfare, but let it slip over time, allowing extremist elements to run rampant.

“For instance, in the case of Monu Manesar, the police found it difficult to arrest him because he had become a hero in the public eye,” said the former ADGP.

Even as gau rakshak Pradeep Dagar holds meetings urging restraint in the use of weapons, he takes a lenient view of vigilante crimes, calling them “killings of passion” by young men.

Also Read: Ghaziabad’s Pinky Chaudhary quit Bajrang Dal to ‘save Hinduism’. It wasn’t aggressive enough

Shooting vs ‘seva’

More than police scrutiny, a devastating self-goal has jolted gau rakshak circles. On 4 September, gau rakshaks in Faridabad mistakenly shot dead Aryan Mishra, a Hindu teenager, during a high-speed car chase.

Pradeep Dagar, the Charkhi Dadri-based president of the Gau Kranti Mission and a member of the Cow Protection Task Force, acknowledged that the incident had dealt a serious blow to gau rakshaks’ reputation.

“Parents have become reluctant to send their children (to us). The incident has cost our image and we are deeply affected by it,” said Dagar, sombrely sipping tea at a dhaba, flanked by two fellow cow protectors.

Now, Gau raksha organisations are working overtime to rebrand themselves. They are sending a flurry of messages on WhatsApp groups, urging members to go easy on using weapons and coordinate more with the police. They are holding meetings to redefine the rules of gau seva.

“We are telling the gau rakshaks that as soon as they receive a tip off, they must inform the police. And unless they confirm the presence of cows in the vehicle, they should not use any arms,” said Dagar, adding that meetings have been held across eight districts so far—Kaithal, Karnal, Jind, Charkhi Dadri, Hisar, Bhiwani, Jhajjar, and Rohtak.

Dagar, a well-respected figure among gau rakshaks, insisted that the Faridabad incident was an isolated case of mistaken identity and doesn’t reflect the true nature of cow protectors across Haryana.

gau.raksha.dal_haryana_

But the fallout has done more than tarnish their public image—it has created a rift between different gau rakshak groups over their methods.

Mahipal Soni of the Gau Putra Sena in Hisar is vocal about distancing his group from the violence. He accuses the Gau Raksha Dal—allegedly involved in the 27 August killing of a Bengali migrant worker in Charkhi Dadri—of encouraging brutality.

“Gau Raksha Dal only believes in maar-peetai (violence), unlike us. We only believe in seva bhav,” Soni said.

But at least on one occasion, witnessed by ThePrint, Soni put this principle aside.

The lure of money isn’t limited to ‘cow smugglers’. While cow vigilantes paint themselves as defenders of religion and animals, financial incentives often drive their operations across Haryana.

Havoc on the highway

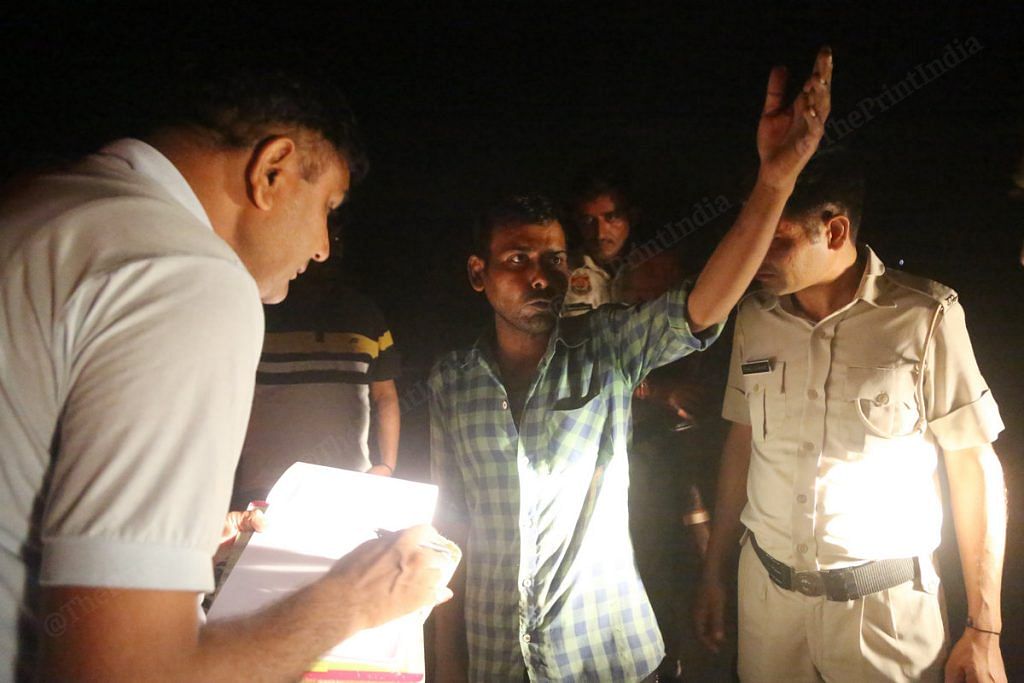

As traffic thinned on the highway, September 6 seemed to be passing uneventfully for a group of Hisar gau rakshaks on night patrol. Then, they spotted it—a truck loaded with cows.

By 11.30 pm, Mahipal Soni was in the middle of the road, slapping the two men aboard the truck—Wasim and Mohammad—demanding they name their employer. Simultaneously, a bovine head count was underway.

“There are around 17 cows!” shouted a juvenile gau rakshak who had climbed to the top of the truck to check the animals.

Soon after that, the police arrived and a case was registered.

Soni explained there are two ways to identify a truck carrying smuggled cows. First, a “pilot vehicle” often drives a few kilometres ahead to ensure the road is clear. Second, if the truck is covered with a tarpaulin, there will usually be a small opening on one side to let the cows breathe.

There are several cow vigilante groups. And when we don’t pay them, our vehicles are confiscated, drivers arrested, and cattle snatched away

-Truck owner

Both Wasim and Mohammad, who said they were only drivers, admitted they were transporting the cows to Uttar Pradesh. Wasim also confessed they were paid Rs 53,000 for the trip. During the preliminary investigation, the police confirmed that the cow transportation documents were fake and lacked the necessary permissions and official stamps from the administration.

For some impoverished families, cow smuggling offers an enticing opportunity to earn quick money. This also appeared to be the case with Wasim and Mohammad.

“This money is enough to run my family for two months. Why would I say ‘no’? I only have to drive the vehicle,” said Wasim, a wiry man in a blue shirt and trousers.

But the lure of money isn’t limited to ‘cow smugglers’. While cow vigilantes paint themselves as defenders of religion and animals, financial incentives often drive their operations across Haryana.

Speaking to ThePrint over the phone, the truck’s owner, who is from Punjab, claimed that he had paid two hefty bribes to get the truckful of cows to their destination.

“On entering Haryana, we paid Rs 20,000 and then we paid again at another toll plaza. There are several cow vigilante groups. And when we don’t pay them, our vehicles are confiscated, drivers arrested, and cattle snatched away,” said the owner, asking to remain anonymous.

He also claimed to have made payments to Monu Manesar, the jailed cow vigilante who is still admired as a hero by some Hindu youth in Haryana.

While Soni denied that his organisation participates in extortion, he acknowledged that some cow vigilantes do. He cited the example of a former member of his group, Gurmeet, who was expelled and arrested in late August for extorting Rs 1 lakh to let a vehicle pass.

“We didn’t hesitate even once to file a complaint against him and ensure he is behind bars,” Soni said.

However, villagers and other critics are growing sceptical about the motives of cow vigilantes. Many ask why these groups don’t take care of the lakhs of stray cattle wandering around Haryana.

Sunil Krantikari had a ready answer to this: “We are not here to ensure the welfare of stray cattle. That’s the responsibility of the state. We want to stop smuggling.”

Meanwhile, the administration is struggling to find a solution to the problem of cow vigilantism and the fanatic violence that often accompanies it.

A Haryana deputy commissioner, who is also the chairman of his district’s Cow Protection Task Force, expressed frustration that they are unable to take firm action against “popular” cow vigilantes because this can snowball into a “political issue”. At the same time, the welfare of cows in general is being neglected.

“Time and again, we have been requesting the Chief Minister and his team to identify grazing lands across Haryana and establish gaushalas there for stray cattle. But we have never received a proper response,” said the DC, who did not want to be named.

Also Read: Lynched Muslim man told fellow migrant workers people in Haryana are nicer than in Delhi

‘Vote for a gau rakshak’

With the Haryana elections set for October 5, gau rakshak Naveen Yogi Parmar, an independent candidate from Charkhi Dadri, is campaigning to be the voice of cows in the state Assembly.

Central to Parmar’s campaign is Pradeep Dagar, who joins him in door-to-door canvassing, urging voters to support a gau rakshak and attend the upcoming Vyavasta Parivartan (Systemic Change) rally on 15 September.

The pamphlet they’re distributing features national icons Bhagat Singh and Ambedkar on the cover, with cows taking pride of place at the top. It opens with the message: “We gained freedom from the British 75 years ago, but not from the systems they imposed…” The pamphlet goes on to discuss cow welfare and the prevention of their slaughter, alongside other issues such as education, food security, and caste discrimination.

“Only when a gau rakshak enters the assembly will the voices of other gau rakshaks and the cows truly be heard,” Parmar declared, as if delivering a speech. His Instagram page, with around 5,000 followers, features calls for Hindu solidarity and pictures from the yoga classes he teaches, but images and videos of cows and gau seva take centrestage.

However, local politicians don’t buy Parmar’s claim of fighting elections for the benefit of cows. BJP leaders, especially, seem irritated.

“If you want to fight elections, go ahead. But don’t say that you are doing it for cows. People have already chosen us to save cows,” said Umed Patuwas, the BJP candidate from Badhra assembly seat in Charkhi Dadri. Parmar is not the only gau rakshak in the fray from Haryana. Bittu Bajrangi, an accused in the Nuh communal violence last year, is also contesting as an Independent candidate from Faridabad.

These are cultural aberrations, not the social norm. These elements want to pitch themselves as saviours, protectors, and heroes

– Jitender Prasad, former professor of sociology

But Dagar insists that only a dedicated gau rakshak can counter the “ineffectiveness” of the police. According to him, if the police had acted more swiftly, gau rakshaks in Charkhi Dadri might not have killed the Bengali migrant worker last month.

“The young men had informed the police beforehand that the Bengalis and Assamese were cooking cow meat. But the police didn’t take any action,” Dagar alleged.

The police, however, offer a different version of events.

“We only get to know about the gau rakshaks’ operations in the morning (after they are over). Even if we want to take any action, we can’t because cows are such a sensitive topic in Haryana that it becomes political at the drop of a hat,” said a senior police official from Charkhi Dadri.

This situation reflects the “pathological tendencies of a society where cow and religion have been politicised,” according to Jitender Prasad, a former professor of sociology from Maharishi Dayanand University.

“These are cultural aberrations, not the social norm. These elements want to pitch themselves as saviours, protectors, and heroes,” Prasad said.

Even as Dagar holds meetings urging restraint in the use of weapons, he takes a lenient view of vigilante crimes, calling them “killings of passion” by young men.

“How could these men tolerate their mother cow being slaughtered and eaten?” Dagar said of the Charkhi Dadri incident, adding that the accused gau rakshaks did not intend to kill the victim.

For Dagar, who claims to have a “scientific temper”, cow protection is tied to the country’s future—and even climate.

“Cows absorb sunlight, which is why their urine and ghee are yellow,” Dagar asserted. “If slaughtering of cows goes on like this, they will vanish from the country, and it will be taken over by devils who exude poison.”

Flanked by two young men in their 20s, who nodded vigorously in agreement, Dagar added that gau raksha is a revolution destined for history books.

“Just like Mangal Pandey fought for Azadi, we, revolutionaries, are fighting for the cows,” he said, as the young men raised their hands in applause.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Haryanvis are not exactly known for intelligence. Even Mr. Shekhar Gupta will acknowledge this.

Besides, Haryanvis do not prioritize modern education for their children. The result is the “scientific temper” seen in the last paragraph of the article.

One correction: Bengalis and Assamese do not consume beef or buff. Muslims do.