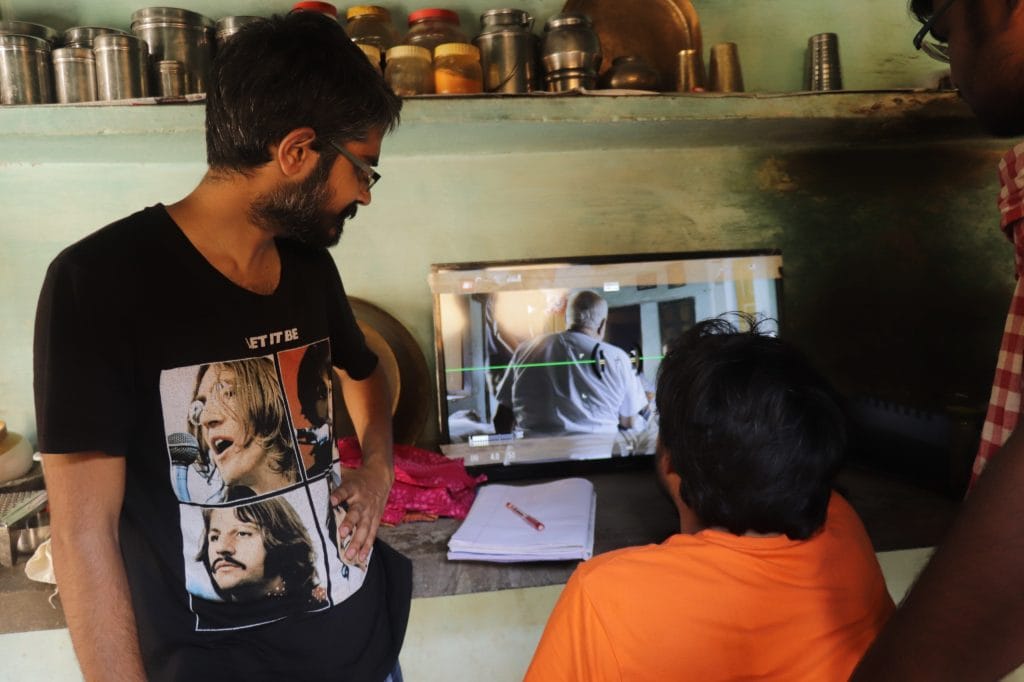

Jind: It wasn’t a regular day in Radhana village. Buffaloes shifted uncomfortably in the background, cow dung perfumed the air, and someone’s old charkha had become part of a movie set. The film Saangi was being shot in a weathered haveli, complete with a creaky big wooden gate, a gandasa, a tool used to cut fodder, and half the village watching like it was the evening news.

On one hand, the actors delivered intense dialogues. On the other hand, 30–40 villagers huddled just out of frame, whispered, giggled, and occasionally burst into laughter mid-scene. And when the director finally yelled “pack up!”, the set transformed into a recovery mission.

“Arey bhai, meri kursi wapas de!” someone shouted, as the villagers rushed in to reclaim their loaned props — benches, stools, even the ancient spinning wheel. For a day, their everyday objects had starred in a movie.

“All my actors were from theatre and got into character days in advance. Despite budget constraints, we managed to finish the shoot. Local people would drop by, spend the whole day watching, and by evening, they would say, ‘Cast me in your next film.’ Some would repeat the actor’s dialogues and mimic them,” said Ravinder Anna Bajwan, the director of the film.

Haryanvi cinema is cracking open its own stereotypes and letting a thousand rebellions bloom. Beyond the nostalgia of hookahs and harvests, a new breed of films is stirring things up with tales that dare, disobey, and disrupt. The first sparks of this change came with Laado (2000), in which a young bride named Urmi walks out of a stifling marriage and demands justice from the village panchayat. There was a quiet on the front, until the pace finally picked up 20 years later. Opri Parai (2022), a TV series confronts the silence around bipolar disorder by smashing the trope of the “possessed woman”. Then there’s Ghar Ki Baat (2025), a comedy series where Haryanvi women hijack Women’s Day celebrations, while the son of the house secretly dates a city girl. In the movie Dhakad Chhoriyaan (2024), fearless young women wield guns, battle drug peddlers, and punch through patriarchy with droll comebacks. And now, storming into this terrain is upcoming Leelaram Minus Raam, a movie currently in production, follows the tale of a queer Jat crossdresser who navigates love, identity, and the fury of a conservative community with glitter in his eyes and defiance in his step.

Haryanvi films are no longer just local spectacles; they’re making waves at international film festivals like Busan International Film Festival (The Limit, 2015), winning awards at National Film Awards (Dada Lakhmi, 2022), and sparking global conversations about regional identity and grassroot stories.

But calling Haryanvi cinema an ‘industry’ might still be a stretch. Behind the buzz lies a messy backstage—unpaid actors, stories of casting couch abuse, and a chronic lack of professionalism. Many so-called filmmakers have jumped in without training, chasing fame and quick money, while skilled artists and technicians remain few and far between. For all its ambition and hustle, the Haryanvi movie industry is where Punjab was in the late 1980s.

But people are stepping up, taking it upon themselves to create culturally rooted, emotionally resonant stories that truly connect with Haryanvi audiences.

“People want to see themselves on screen. Haryana has countless untold stories, and as SUPVA students, we feel it’s our duty to bring them to life. Yes, filmmakers here have found success, but doubt keeps returning—people start to question the value of cinema. I want to change that. Because without the freedom to tell our stories, how will we ever truly understand who we are? Cinema isn’t separate from us—it is us,” said Manasvi, a student at Dada Lakhmi Chand State University of Performing and Visual Arts (SUPVA).

Building a foundation

In the courtyard of a modest campus in Rohtak, the conversation swings from Andrei Tarkovsky to Anurag Kashyap. “Did you finally watch Tokyo Story?” one student asks another, eyes lighting up. “That scene with the empty hallway? Ozu kills you with silence, yaar.” Nearby, two others argue over which Scorsese film has the tightest edit. Someone is scribbling a screenplay in their notebook. Another is carrying a cracked DSLR. One would think this is FTII or a backlot in Mumbai.

But this is SUPVA — Dada Lakhmi Chand State University of Performing and Visual Arts — Haryana’s quietly radical experiment in cinema. Tucked away in Rohtak, it’s the only university in Asia offering full-time bachelor’s degrees in acting, direction, cinematography, and other core filmmaking disciplines. Founded in 2011, SUPVA is not just a college — it’s a pressure cooker of raw ambition and cinematic obsession. Many of its students don’t dream of Bollywood. They want to tell stories that sting, that matter for local viewers.

Still, the reality is far from cinematic. “Honestly, a lot of students come here thinking it’s an easy escape from engineering or government exams,” said Nehra, a professor and an alumnus of the very first batch.

In the classrooms, film theory shares space with frustration. Four-year courses stretch into six because of delays and red tape. “There are students still waiting to graduate years after finishing their coursework,” said Manasvi, a fifth-semester direction student. “It breaks morale.” The spirit is willing — but the system, often, is stuck in a loop of outdated equipment, administrative limbo, and slow evaluations. Yet, through all this, the students persist — stubborn, sharp, hungry.

Haryana has countless untold stories, and as SUPVA students, we feel it’s our duty to bring them to life. Without the freedom to tell our stories, how will we ever truly understand who we are? Cinema isn’t separate from us—it is us

Manasvi, student, SUPVA

That same hunger lives online — in an app called Stage, launched in 2019 with one audacious goal: telling stories in dialects the mainstream ignored. “Forget English. Forget even standard Hindi. Let’s speak in our mother tongues,” said co-founder Vinay Singhal. Today, Stage hosts a river of Haryanvi, Rajasthani, and soon Bhojpuri and Magahi content — from films to folk music to Nukkad Nataks. It has over 4.1 million paid subscribers and a reach of 36 million.

“People used to mock Haryanvi — call it crude, backward,” Singhal said. “Now they say, ‘Apni bhasha sun ke maza aa gaya (It felt great to hear my own language)’ That’s our real metric.” Unlike mainstream OTTs chasing gloss, Stage is chasing roots. “We’re not just building the Netflix of Bharat,” he said. “We’re building a cultural space. If someday we have to make a Disneyland for Haryanvi, we’ll do that too.”

Also read: Haryanvi songs are moving from vulgarity to veil — ghoonghat is sexualised, male gaze the muse

The two faces

Mattresses blocked the sounds from windows and doors, silencing the world outside, an LED TV flickered in place of a monitor in the kitchen. And when someone finally called out, “Lights, camera, action!”—the director’s father stepped out of a room, buttoning his shirt, unaware he was a brothel client in his own home.

In Kalanaur, Haryana, the director’s 1910s haveli transformed into a set no one in the town knew about. The setup was improvised—two crew members holding up a clothesline, as there were no walls tall enough to tie it to. For 15 days, the crew stayed in the house, while the director’s mother cooked for them. Between takes, the shoot would pause as DJ music blared from the neighbourhood, and through the scorching June heat, they pressed on.

“When my father watched Pinjre Ki Titliyan and realised what the film was actually about, he was very upset. He said, ‘You did this with your own father? That wasn’t right.’ My parents didn’t like the film at all. My father even hurled quite a few abuses,” said Ashish Nehra, the director.

The film unfolds in the stifling world of a brothel, where girls like Rukhsaar inherit a fate they never chose. But Rukhsaar refuses to be sold. In one haunting scene, she loses her virginity with a candle, destroying the very thing that made her ‘valuable’ to the system. By dawn, she lies on the floor, a bloodied candle beside her. Her laughter and sobs blur, her body heaves — unmoored from rules, from reality. In her pain, in her madness, she is terrifyingly free.

“This film was born from the world we refuse to talk about,” said the debut director. “I saw a friend fall in love with a sex worker. He was thrown out violently. But what struck me most was that the women never really had a choice — not even in marriage. If things are wrong, it’s still the woman who must decide. I cried while writing Rukhsaar’s story,” said Nehra, who’s also an actor.

This isn’t the Haryanvi cinema most are used to. Traditionally, the industry has churned out films centred on two extremes: the submissive woman bearing the weight of family honour, or the rebellious one punished for stepping out of line. Drama is heavy, endings are clean, and patriarchy—more often than not—is simply rearranged, not challenged. And this has not magically disappeared.

Films like Duj Var (2022) follow a familiar pattern — women suffer, men dominate, and systemic issues go unchallenged. Trauma is packaged as drama, and even so-called critiques of patriarchy end up reinforcing it.

Even recent films like Safe House (2021) double down on caste and honour tropes. Directed by Ramesh Chahal, it shows nine couples escaping their villages to marry for love—only to be hunted down and killed, not as victims, but as moral examples.

“There was a time when girls knew every boy from their village was like a brother. The Constitution didn’t mention this — but maybe it should have,” said Chahal. For him, the film is deeply personal, a reflection of his own pain and what he sees as the loss of ‘sanskaar’ in today’s youth. In the end, the runaway couple is killed by villagers — not as a tragedy, but as a warning. The film, he claims, was taken seriously by Khap leaders.

In DJ Wale Babu (2022), the song ‘Pandit Ji’ sparked controversy by suggesting that murder is written in the hands of a pandit—raising questions about caste stereotypes and whether a Brahmin character could be portrayed as a killer.

Meanwhile, Tera Mera Vaada (2012) pulls off a sudden time leap with zero setup—it just jumps. In Dada Lakhmi, set in the early 1900s, even the cows have plastic ear tags for insurance. Then comes Safe House, where a 10–12 year time jump lands with no physical or emotional change in characters—same makeup, same body language.

But Pinjre Ki Titliyan marks a rupture. It doesn’t seek male validation or offer tidy resolutions. It takes viewers on a raw, unsettling journey of self-reclamation and freedom, free from male validation or societal approval.

Women who watched the film wept, embracing the director, recognising their own buried truths in Rukhsaar’s defiance. The film was widely celebrated across the national and global circuit, making an impact at festivals like the Northeast India International Film Festival 2022 and BIFF Mumbai 2022. It also garnered international recognition at the Love and Hope International Film Festival 2022 in Spain and the Nashville Play Film Festival 2022 in the United States.

In the same breath, films like Opri Parai (2022) are pushing boundaries too. A psychological thriller woven with supernatural threads, it explores mental illness and caste trauma in rural India. The film was widely praised, yet the director never returned with another project. Instead, following the success of Opri Parai, a six-episode web series titled Opri Hawa was released—but with a different director.

“New talent isn’t encouraged—neither by OTT platforms nor by producers,” said Nehra. “They only want content that can go viral and fit neatly into their business model. There’s no real support system, no producers backing fresh voices, no sustainable model in place.”

We’re building a cultural space. If someday we have to make a Disneyland for Haryanvi, we’ll do that too.

Vinay Singhal, co-founder, Stage

Cinema craze

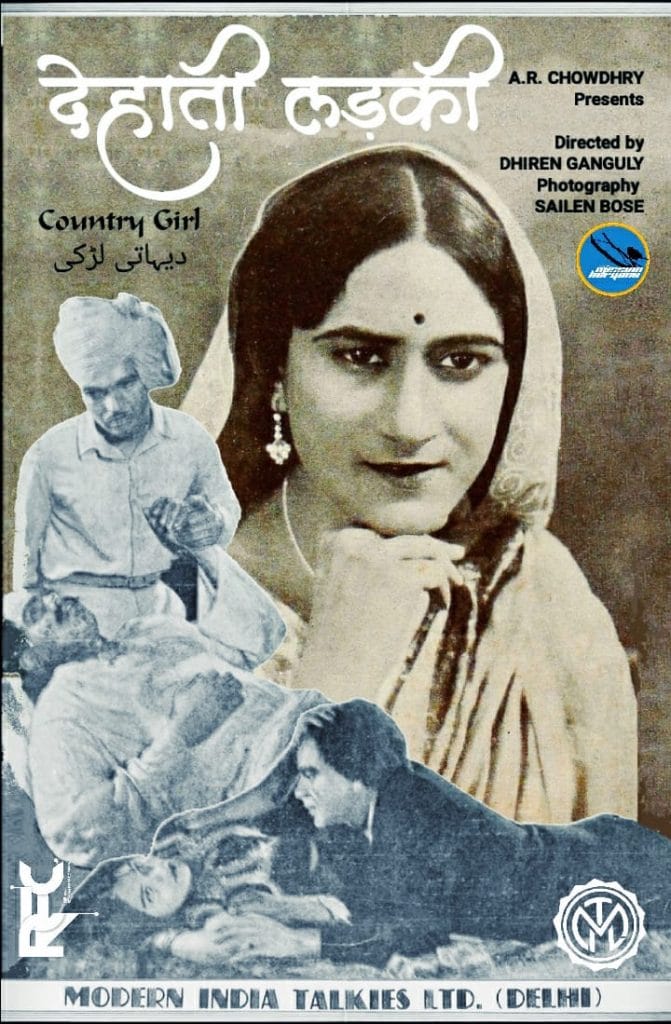

Haryana’s tryst with cinema isn’t recent — it goes back nearly a century. In 1936, the region saw the release of Dehati Ladki, considered the first Haryanvi-language film. Shot in black and white, it marked a quiet but significant beginning for Haryanvi cinema, rooted deeply in rural life and local dialect.

In the early 1980s, a quiet revolution stirred in Haryanvi cinema. It was led by a group of young idealists, many of them fresh graduates from FTII, Pune. Among them was Sumitra Hooda — a fierce, clear-eyed trailblazer who would go on to become Haryana’s first female paratrooper, its first female radio announcer, its first woman to take the stage as an actor, and the lead in Bahu Rani (1983), the state’s second color film (following Harphool Jaat, the first).

Local people would drop by, spend the whole day watching, and by evening, they would say, ‘Cast me in your next film.’ Some would repeat the actor’s dialogues and mimic them.

Ravinder Anna Bajwan, director, Saangi

Bahu Rani was the first Haryanvi film to be made in Haryana by its own people. Hooda and her friends were still students then. Actors Shashi Ranjan and Rakesh Bedi had just graduated from FTII, and none of them had the resources to back a full-fledged film. Some sold their scooters. Others mortgaged family land. That’s how Bahurani came into being.

The film dared to challenge deep-rooted taboos—a widow forced to marry her mentally disabled brother-in-law. The film wasn’t technically perfect, but it was raw and real—and it opened the doors for Chandrawal.

In 1984, Chandrawal became a cultural phenomenon, its powerful emotional story and JP Kaushik’s unforgettable music turned it into Haryana’s first true box office triumph.

The film tells the tragic love story of Chandrawal, a girl from the nomadic Gadia Lohar tribe, and Suraj, a Jat boy. Bound by tradition, her tribe forbids marriage outside their community. When their forbidden romance is discovered, both families react with fury. In the climax, Suraj sacrifices his life to protect Chandrawal, who, devastated, takes her own life.

While Bahu Rani was appreciated by those who saw it, the film didn’t receive the publicity or promotional push that later Haryanvi films did. “When Chandrawal in 1984 came, it was produced by Usha Sharma and directed by Jayant Prabhakar. Prabhakar was in PR. So it had full backing from the government’s publicity department. Posters in every village. Cars with speakers. You name it. We didn’t have that. We were still collecting money to finish our film,” said Hooda.

The film was a massive hit and ignited a cinema craze that no one in Haryana expected.

“The film earned Rs 3 crore—an incredible feat for a Rs 3 lakh budget,” said Yashpal Sharma, a Haryanvi actor who has also worked in Bollywood. “People were so invested in Haryanvi cinema that they sold land and homes just to be part of the next film.”

For a brief period, it seemed like Haryanvi cinema was on an unstoppable rise.

What followed was an outburst of enthusiasm — but not necessarily expertise. Seeing the profits Chandrawal brought, filmmakers mushroomed across Haryana’s towns and cities. They were jewellers, cycle salesmen. They’d make their own sons into heroes, boys who’d never done any theatre. Heroines came from Bombay, and so did the technicians—people who charged less but gave nothing new. Quantity increased, quality fell. Films lacked proper sound, structure, or visual storytelling. They didn’t even bother with scripts. Often, the financiers were also the lead actors.

Chail Gabru (1986) tells the tale of a young man falsely accused of theft on his wedding day, forcing him to leave the village and later return to clear his name. Funded by a local jeweller, it starred his nephew in the lead role. Two years later, Bhabhi Ka Ashirwaad (1988), backed by property dealers chasing profit, followed a village love story where the hero wins support from his sister-in-law to marry his beloved.

“At that time, many property dealers and businessmen ventured into the film industry simply because they had the money. They believed they could earn profits by making films,” said Sushil Saini, a film historian and writer. “But they lacked even the basic understanding of filmmaking—there was no sense of craft. The actors, often untrained, would deliver lines loudly and without any emotion.”

The audience noticed. The novelty wore off. The heartfelt folk tales and melodies were replaced by diluted copies of Bollywood hits, and viewers tuned out.

“The audience thought that films were nonsense,” said Arvind Swami, the director of Bahu Rani. “So, the interest of the public also started diminishing. 62 films were made after my movie.” And many of those flopped. Dreams faded. Finances crumbled. Haryanvi cinema was on life support.

[In the 1980s] people were so invested in Haryanvi cinema that they sold land and homes just to be part of the next film..

Yashpal Sharma, actor

After 1988, the region saw a long lull in filmmaking, with no notable releases until the year 2000, when Laado marked a significant return.

Also read: Punjab is undergoing an indie film revolution. Challenging the Jatt Sikh domination in cinema

Escaping cringe territory

It wasn’t that people didn’t try to create something meaningful, but by then, the magic of the theatre had faded. There were rare glimmers of hope—films like Zar Zoru Aur Zameen (1989), Gulabo (1986), and Sanjhi (1984). Then came Laado in 2000.

Laado, directed by Ashwini Chaudhary, managed to draw an audience initially, but its climax, where a woman exposes her husband’s neglect and her lover’s betrayal, demanding justice in a society that had already condemned her, didn’t sit well with many and the film didn’t do well financially.

“That film gave us hope again,” Sharma said. But that hope was short-lived. “For sixteen years after Laado, nothing was made. It was like a drought had hit Haryanvi cinema.”

During that gap, it was like a barren desert—nothing. And even if one or two films came out, they were such low-budget productions that they hardly counted. There were no films in the theatres, and if they were there, no one went to watch them. In the absence of structure, the industry slid into cringe territory—YouTube was flooded with garish music videos.

A few films tried to steer it back: Pagdi (2014), Satrangi (2016), and Chhoriyan Chhoron Se Kam Nahi Hoti (2019)—all National Award winners. But no one showed up. “The films were good, but we didn’t know how to market them,” Sharma said. “We had no distribution.”

That’s when Sharma decided to act. Inspired by his time on Lagaan, Sharma set out to make a film with the same honesty and heart. Pandit Lakhmi Chand, Haryana’s legendary poet, storyteller, and reformer, became his subject.

Sharma spent five years crafting Dada Lakhmi, a musical based on the life of the poet, pouring in his acting earnings to fund top talent for his film. “I would act, get paid, and put the money straight into the film,” he said.

When it finally released, every show ran houseful for 15 days. “Five thousand people came—just to watch Dada Lakhmi.” It went on to win 107 awards, was screened online at a festival happening in Cannes during the second COVID wave.

It’s now being taught in cinema and mass communication courses in Raja Mansingh Tomar Music & Arts University Gwalior and Kandivli Education Society’s BK Shroff College Of Arts, Mumbai.

Sharma said Haryanvi cinema lacks both serious filmmakers and strong storytelling. “Everyone talks about women empowerment, but no one makes those films,” he said. For him, the goal is clear: blend art with commerce. “Quality cinema should earn money too—like 3 Idiots, 12th Fail, Bheja Fry, Satya. They didn’t compromise on quality. Dada Lakhmi is in that league. That’s my aim—films that are both artistic and commercially sound.”

Cultural disconnect

Even the music—once the beating heart of Haryanvi cinema—began to lose its soul after the 1990s. In its golden days (1980s), composers like JP Kaushik and Vedpal Verma created melodies deeply rooted in Haryana’s folk traditions. But over time, originality gave way to imitation. Songs were lazily lifted from Rajasthani or Bollywood hits, passed off as Haryanvi. But the cultural texture, the authenticity—it simply wasn’t there.

And with it, stories became hollow—love angles without depth. Action without emotion. “The acting was stiff, the dialogue flat. Some didn’t even use proper Haryanvi—just a word at the end of the line,” Saini said.

He remembers a film called Kunba—a word-for-word remake of Rajesh Khanna’s Avtaar. “Same plot, same Hindi dialogues. What’s the point of calling it a Haryanvi film then?”

Nobody explored the state’s rich dialects and cultural textures. “Sirsa speaks differently from Ambala or Rewari. But the films felt generic—like they belonged nowhere,” said Roshan Verma, a casting director and researcher. Outside investors didn’t help. “People from Delhi—parotta sellers—put in money hoping for quick returns. But when films flopped, they disappeared. No posters, no publicity. Sometimes people didn’t even know a film had been released.”

It all added up: bad direction, emotionless acting, copied music, cultural disconnect.

Director Rajeev Bhatia, who made Pagdi, echoed the frustration. “There are baby steps, but it’s hard. I thought my film would bring crowds. It didn’t.” He pointed to the difference: “Punjabi films have support from the UK, USA, Canada. Haryana has none of that.”

Distribution was another hurdle. “When I made Pagdi, there was no OTT, only theatres. But Haryana barely has a hundred screens. Compared to 8,000 across India, we’re a dot,” Bhatia said.

And that wasn’t the worst of it — the exploitation ran deep. “Directors would cast a heroine on the condition that she had to make her way through three or four men,” said director and actor Nehra.

Verma also said that the industry operates in an exploitative manner.

“Haryanvi cinema has a lot to learn from Punjab,” said Verma, who’s worked in both industries. “Here, people call you ‘bhai’ just to haggle over fees. There’s no sense of professionalism in Haryana. It’ll take years before we can even call it an industry. Most think adding fights and abusive scenes makes a hit. Only a handful care about real cinema—the rest just make half-baked films to boost their egos.”

Punjabi films have support from the UK, USA, Canada. Haryana has none of that.

Rajeev Bhatia, director

TV series like Akhada (2022) and its sequel have performed exceptionally well on OTT platforms, and director Sanjay Saini is now gearing up to create more such content. “Despite everything that’s wrong with the Haryanvi industry, we’re still pushing to break the stereotypes and build an ecosystem known for strong storytelling, skilled filmmaking, and a safe, professional environment,” he said.

Also read: Hyderabad’s Annapurna Studios is India’s high-tech film hub. A 50-yr Nagarjuna family legacy

Good quality cinema

In Vashikaran (2024), co-director Ashish Jangra immerses the audience in a chaotic world of black magic, caste tension, and dark comedy. Set in a Haryana village, the film follows an upper-caste family’s obsession with a lower-caste man believed to practice black magic. Fearing his power, they plot to kill him, only for him to die before they can act, leading to a bizarre mix of rage, fear, and retribution.

“The central theme of the film is casteism,” Jangra said. He wrote the script in a café in Haryana in 2021, inspired by a real incident from his village, Karota. “There was a Valmiki elder named Ramniwas—a respected tantric. The whole village feared him.”

His film doesn’t shy away from brutality. In one scene, the sarpanch growls: “Let him die first. Then we’ll strip the women of his house and hunt down his people like animals.” Jangra said that the Mirchpur incident was a key inspiration.

Jangra has long been drawn to unconventional stories. Back in 2005, he wrote Leelaram Minus Ram, a raw tale about Leela Ram—a gay Jat cross-dresser from Haryana. Embraced by village women and the saang (folk theatre) community, Leela dreams of becoming a woman, but struggles with identity, even forced to wear a mustache to appear “normal.”

In the final scene of the film, while applying for an Aadhaar card, he’s asked his name. He simply says, ‘Leela.’

“It’s about identity,” said Jangra. “He wants to remove ‘Ram’ from ‘Leelaram’—to just be Leela.”

For Jangra, satire isn’t just a stylistic choice — it’s a political act. “Casteism in Indian films has always been shown with tears and trauma. I wanted to explore it through absurdity and dark humour—because no one’s doing that. Satire is my strength.”

A similar spirit is seen in Haryanvi actors too. Female directors are taking up the responsibility of making good quality cinema.

Sonia Saharan, a filmmaker who graduated from SUPVA in 2016, recalls her journey in a field still dominated by tradition and boundaries. “I was the only girl in my batch of 32,” she said.

Saharan’s first film, Daira – The Limit, was a short that won multiple awards, including recognition at the Haryana International Film Festival (HIFF), a private film festival and in South Korea at the Busan International Film Festival. “I wanted to tell a story from Haryana, but with a different lens,” she said. The film explores the struggles of boys and girls in Haryana who are bound by societal expectations, using her village as a raw, authentic backdrop. “In our villages, boys have boundaries too,” Sonia said. “Even going to school comes with limitations. But girls, their boundaries are even tighter.”

Anjvi Hooda (31), a key figure in Haryanvi film and theatre, began on stage and trained under Bollywood veterans like Satish Kaushik and Jaideep Ahlawat. Now, she has opened her own studio, Anjvi Films in Rohtak, and is all set to make her directorial debut soon.

One of her standout works is Chhaya (2021), a short film set in the 1980s. It follows Rakesh, torn between his children from a previous marriage, a demanding new wife, and a mortgaged well—all while questioning deep-rooted beliefs about family and sacrifice.

Chhaya is a layered exploration of identity, sacrifice, and rural social pressures. Despite being a student project and the degree film of SUPVA, the film made an impressive mark—it was screened at the Mumbai International Film Festival and selected for the Cannes World Film Festival in 2022. It also earned spots in the “Short Fiction” category at the Dada Saheb Phalke International Film Festival (Mumbai), the International Kolkata Short Film Festival, and the Chennai International Documentary and Short Film Festival.

Film policy and hope

The Haryana Film and Entertainment Policy–2022 promised a new dawn for regional cinema—subsidies up to Rs 2 crore for films shot in the state, with half the budget reserved for Haryanvi-language projects.

Only 12 films would be selected each year to ensure quality over quantity. Film cities were to rise in Pinjore and Gurugram, an online portal would simplify permissions, and institutions like SUPVA would nurture young talent. Haryanvi films, it was said, would even return to Doordarshan, one per week. Awards, recognition, a cinematic revival—all written into policy.

“The policy looks great on paper, but it hasn’t really been implemented,” said Yashpal Sharma. “The government just isn’t doing enough for cinema.”

Still, hope flickers. Artists haven’t given up.

Every morning, casting director Verma walks to a vast, empty stretch of land in Pinjore—the site where Haryana’s first film city was supposed to be built. It’s been nearly three years. The land lies quiet, untouched. No sets, no cameras, no voices.

He laughs, half-sarcastic, half-sincere, as he dials his actor friends. ‘Mere Karan Arjun, tum kab aaoge (My Karan and Arjun, when will you come)?’ he says, standing alone.

“I wait for the day this silence is broken by the sound of clapperboards and dialogues,” he said.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)