Bilimora, Gujarat: It’s not every day that gold falls from the sky, but that’s exactly what happened to four labourers pounding away at a 100-year-old house in Bilimora village in Gujarat’s Navsari district. The wooden beam ripped open, and a cascade of gold coins, a started raining down.

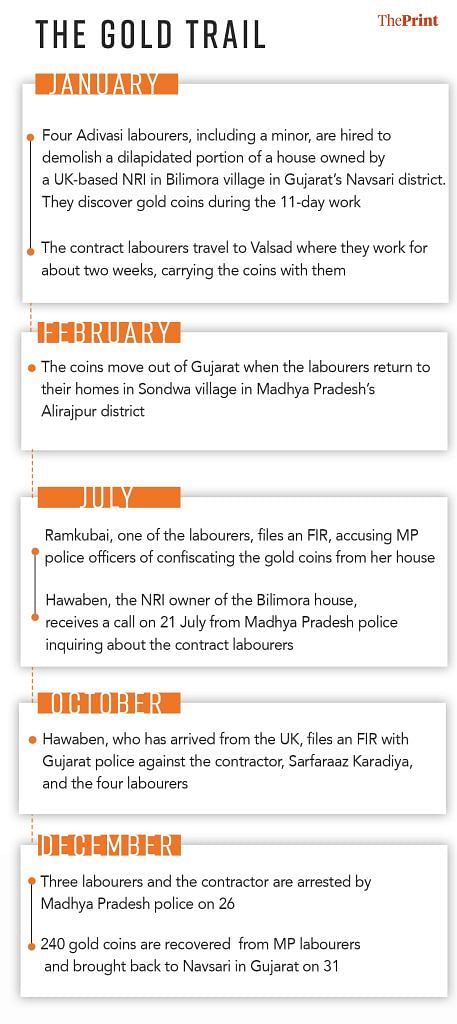

That was in January 2023. Believed to be from the British-era, the 240 coins, worth Rs 1.11 crore, travelled with the labourers from Bilimora to Valsad in Gujarat and then to Sondwa, a tiny village in Madhya Pradesh’s Alirajpur district, where they remained hidden—until a police raid, tribal protests, and allegations of the Madhya Pradesh police stealing the coins surfaced.

As word spread and images of one solitary coin went viral, it triggered a frenzied gold hunt involving law enforcement from two states. Four policemen from Alirajpur in Madhya Pradesh were suspended, tribal families were arrested, and the Navsari police crime branch in Gujarat visited Madhya Pradesh five times in less than two months.

They doggedly tracked and retrieved the cache from the labourers and even a local jeweller. After months on the trail, the police team returned to Gujarat with 240 gold coins in December 2023. Since then, the gold has captured the public imagination—drawing historians, police officials, lawyers, and courts into the debate.

Everyone, from the contractor to the labourers, the ASI, and the owner of the now-demolished ancestral property—an NRI who flew from Leicester in the UK—is asking the million-dollar question: Who gets to keep this fortune? The hoard could well be a national treasure—and the quaint ideas of ‘finders keepers’ and ‘owners keepers’ are not cutting any ice with the government.

The gold coins, each bearing an engraving of King George V and weighing 7.98 grams, are now under lock and key in a safe at the police warehouse in Navsari. They appear almost newly minted, gleaming in burnished gold with thick ridged edges. And nobody, except the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and the police, has access to them.

“This is part of a special series of coins that began to be issued during the 15th and 16th centuries and continues to the time of Queen Elizabeth, Victoria, as well as King George V,” says Abhijit Dandekar, a professor of archaeology at Deccan College, Pune.

The mystery is how they were hidden for so long. A senior police officer suggested that because they were secured in a wooden box and stashed on one of the high beams of the dilapidated house, it evaded notice for decades. For the Navsari police team, the retrieval is a job well done. It’s not often that they get to go treasure hunting.

“It was a big exercise that involved a lot of back and forth from Gujarat to Madhya Pradesh. So much wealth has not been recovered before (in the district). And it’s not silver, but gold,” says Sushil Agarwal, Navsari district superintendent of police.

Also read: Gujarat GIFT city has been holding its breath for greatness. It’s a lifeless ghost town now

The day it rained gold

When Hawaben commissioned the local contractor Sarfaraz Karadiya to tear down her husband’s portion of the two-storeyed ancestral home, nobody gave it much thought. It was one of many old houses on a quiet street in Bilimora, its main door opening straight onto the wide street, the once-vibrant paint faded to a muddy green after 40 years of solitude.

The JCBs had already razed part of the structure, and Karadiya brought in a group ofAdivasi labourers from Sondwa village in the tribal district of Madhya Pradesh’s Alirajpur with JCBs to tear down the wooden beams inside. He wasn’t even on the site the day it started raining gold.

Two of the workers, Raju Bhaydiya and his wife Bajri, were on the ground floor with their shovels and hammers when they heard clanks, clunks, and thunks. As they looked up to the first floor through the gaping hole in the ceiling, they were pelted with coins hurtling towards the ground from a height of at least 12 feet. In a daze, they started collecting the coins, not informing the other two workers, also their relatives, Ramkubai Bhaydiya and her minor son.

“It shows there was distrust between the individuals,” says the SP, piecing together the sequence of events based on their statements to the police. But Ramkubai and her son heard the commotion, rushed down from the top floor, and started helping themselves to the gold. It was more wealth than they had seen in their lifetime.

The now-demolished house was one half of an ancestral property belonging to the Baliya family from Bilimora. A portion of the property, painted in a bright orange, brims with life—it’s home to Hawaben’s brother-in-law, Shabbirbhai Baliya, one of three brothers who grew up here. (The third brother who sold his share of the property to Hawaben is in Australia.)

But two months ago, the decrepit portion of the house crumbled. Panic gripped Shabbirbhai’s family as cracks ravaged parts of their house as well. The two houses share a backyard and a core interconnecting wooden beams and pillars. Frantic calls were made to Hawaben’s family in the UK, who came to India to make arrangements to raze the structure.

Karadiya was given the contract. He lived in a neighbouring town but was known to the family, and work finally began in January 2023. None of the labourers informed Karadiya of the stash of coins. Nobody was monitoring them either as they engaged in a seemingly inconsequential task.

For several days after the discovery, Raju, Bajri, and Ramkubai and her son worked on the house, pulling down every brick, beam, and bar. They chatted with members of the Baliya family but made no mention of the gold.

“Despite being in such close proximity, we knew nothing about this gold,” said Shabbirbhai’s son Shoaib, who is in his 30s.

On the 12th day, the workers left. Their contractor had another job for them in the neighbouring town of Valsad. They completed that task by the end of February and returned to their homes in Sondwa village in Alirajpur district, Madhya Pradesh.

For months, the gold coins remained in the village, until the police raided Ramkubai’s house in July.

Also read: Morbi is India’s undisputed tile champion. Now this Gujarat town is eyeing China’s crown

The discovery

Flush with gold, Raju and Ramkubai started making changes in their lives. They installed tubewells and an irrigation system in their fields. One of Ramkubai’s relatives bought a motorcycle, another bragged about his plans of buying a car. Murmurs began about the source of their newly acquired wealth. Villagers, according to the police, were convinced they had started a bootlegging business.

Then, heads rolled when Ramkubai took a few coins to a local jeweller, Gopal Omprakash Gupta. Whispers grew louder. Now, everyone was talking about her ‘strange’ gold coins. The Sondwa police’s network of khabri (informers) picked it up, and on 19 July, a team of four policemen raided Ramkubai’s house under the pretext of cracking down on the bootlegging business.

The following day, Ramkubai marched straight to the Sonwada police station and filed a complaint against the four officers—SHO Vijay Devda and constables Rakesh Dawer, Suresh Chauhan, and Virendra Singh—accusing them of stealing her share of the gold coins. By then, the village was in an uproar, with residents claiming that the police were targeting and harassing Adivasis.

“It became a law and order situation in Alirajpur, which has around 97% tribal population. The case was being seen as police harassing the tribal villagers. And it was unfolding around the time of the [assembly] election,” said a police official from Navsari. Barely three weeks ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had kicked off the BJP’s campaign for the December election with public rallies in the state.

Worried that the protests would become a flashpoint during the election, the Sonwada police took immediate action. Based on Ramkubai’s 20 July complaint, an FIR was filed against the four policemen under Section 379 of the IPC for allegedly stealing 240 gold coins. A special investigation team (SIT) was formed by the Madhya Pradesh police to probe these allegations.

In Leicester, Hawaben was awakened by a call the next morning. It was from an acquaintance whom she had entrusted with keys to the now-demolished house. “Police from Madhya Pradesh have come to your house,” Hawaben recollected the panicked call. Later, the MP police reached out to her directly.

“They asked if I had hired the contractor Karadiya. Then I learned that gold had been found during demolition,” she added.

Her brother-in-law and his family next door were also questioned. Shoaib, who runs a chicken shop, was in the US when his family informed him about the arrival of police. He too received a similar call.

“They informed me that the MP police had come to our house with the labourers to see the demolished property and told us to come to the police station to talk,” he said.

By then, the Navsari police in Gujarat were aware of the missing gold, but were forced to remain on the sidelines. They could not take up an investigation because the FIR had been registered in Madhya Pradesh.

But by October, Hawaben returned to Bilimora with a hundred questions about the missing gold. She filed a complaint against the tribal families, including the contractor. That was enough for the Navsari police to plunge into the case. They filed an FIR charging the labourers and the contractor under Sections 406 (criminal breach of trust) and 114 (abettor present at the spot when offence is committed) of the IPC.

It became a race for who would find the gold coins first—the Navsari police or their counterparts in Madhya Pradesh, who had a three-month headstart.

Also read: MP’s Nepanagar forest is the new battleground. IPS, IFS, tribals, activists, mafia at war

How the Gujarat police cracked the case

SP Sushil Agarwal deputed three teams of 15 policemen whose main task was to hunt down the labourers. In two months, the teams took turns to make the nearly 300 km journey to Alirajpur five times.

The police had only seen an image of one coin carried in the media.

“The local police weren’t very cooperative because of the previous case involving suspension of policemen. We had to be in disguise to get an idea of the movements in the village,” said an investigating officer.

To get information, the team dressed in plainclothes and started mingling with the tribals. The undercover operation was carried out over five visits in two months.

Through snippets of gossip overheard and shared with them at Alirajpur’s marketplaces and village centre, the undercover cops learned about Ramkubai renovating her house. The rumour mills were high on grist, but getting to the tribal families was proving to be a bigger challenge than the police anticipated.

“The terrain was treacherous, their houses were located on top of hills,” said one of the investigating officers. At one point, two police personnel fell and returned to Gujarat. Another investigating officer suspected that Ramkubai and the others could evade them easily because of the support of local people.

Two night operations of the Navsari crime branch had failed. Eventually, the police caught up with all four—Ramukbain, her son, Raju, and Bajri—on the afternoon of 26 December.

After their arrest, the Navsari crime batch were able to retrieve the gold coins within days—175 from Raju and Bajri, and 24 from Ramkubai. Some were buried in their fields; another batch was hidden in rice sacks. The police also tracked down and collected 41 coins from Gupta, the jeweller. Ramkubai and Raju’s brother had pledged them for a loan.

According to Prof Dandekar, who is also a numismatic expert, the coins were not meant for transaction in India. The shiny state in which they were found indicates that they were “not in circulation or used” at any point.

The Navsari police did some digging too, and found that they were sovereign gold that were minted in London, Canada, and Australia between 1917-1931. “But for one year, in 1918, they were minted in Bombay, which might explain them ending up in Bilimora, a dockyard town under the Gaekwad Dynasty,” said SP Agarwal.

Whose gold is it?

The last few months have been surreal for Hawaben who has yet to see the now infamous gold. Shoaib, too, is trying to make sense of what happened. When the police reached out to the family, he immediately got in touch with the contractor, who only learned about it through the media. But he has been telling everyone that there are more coins to be found.

“Karadiya initially told me the labourers got 700 coins. When I pressed further, he said 900 coins and then eventually he said they got around 1,900,” Shoaib said.

The discovery of the coins didn’t come as a total surprise to the family. Shoaib had grown up on stories of how his ancestors were wealthy. “There were tales of how my forefathers used to give loads of gold to their daughters during weddings,” he said.

Hawaben is still in India with her father in Rankuva village near Bilimora. She’s not sure what her next step will be, but it probably involves lawyers.

“For now, the police are doing the work. I will talk to them and think about what to do next,” she said.

Police insist that Hawaben must prove her ownership, while the four Adivasis who stumbled upon the treasure have already staked their claim. Meanwhile, the ASI in Vadodara studied the coins and is writing its report. “We will wait for the report, before deciding what to do next,” says the SP.

More than a year after it rained gold coins, there’s no trace of the old house. The ground has been cleared of debris and evened out. But Hawaben and Shoaib are not satisfied with the outcome. Where are the coins that the four Madhya Pradesh policemen took off with, they want to know.

“It’s not just 240 coins. There are more. So I have told the police to search for them,” says Hawaben.

Everybody is convinced that there’s still another pot of gold somewhere between Bilimora and Alirajpur.

(Edited by Prashant)