Kannauj/Khurja/Muzaffarnagar (UP): Moni Rajput still can’t accept that her 16-year-old daughter killed her own father. She’s torn between two explanations—either a murderous stranger or someone brainwashing her daughter.

“Iska brainwashing hua tha. Can a girl kill her own father, that too with such a weapon?” Moni said, petting the family’s dog absent-mindedly at their two-storey house in Kannauj’s sleepy Karmulla Pur village. Then another thought struck her: “Even our dog was not spared. It must have been an outsider. Why would she put chloroform on Sheru?”

Moni is haunted by the image of her husband, Ajay Pal Rajput, lying lifeless with his neck brutally slit by an aari patta—a crude local hacksaw. All the evidence points to their 16-year-old daughter as the killer, allegedly with the help of her boyfriend. Both are now in separate juvenile homes—he in Farrukhabad, she in Barabanki.

The crime rocked Kannauj’s Chhibramau tehsil. This wasn’t a typical “honour killing” or spurned-lover saga. It was darker.

Yet, open any tabloid in the Hindi hinterland and twisted stories of love and murder are reported in detail almost every day, distinct from the kinds of honour killings often seen in Haryana. Across rural Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and beyond, prem prasangs (love affairs) seem to be turning deadlier, more brutal, and increasingly gender-agnostic. They are increasingly going the messy murder-Manohar Kahaniyan way—daughters killing fathers, lovers turning into murderers, families torn apart by rage and revenge.

‘Prem prasang ke chalte chhote saadu ne bade saadu ki gala ret kar kar ki thi hatya’ (A love affair leads to younger brother-in-law slitting elder brother-in-law’s throat), screamed a recent headline from UP’s Gonda. Another blared, ‘Prem prasang ke chalte do pakshon mein khooni sangharsh’ (Love affair starts bloody feud between two families). ‘Mahila ke prem prasang ke vajah se nabalig ladke ko mili khaufnaak maut ki saza’ (Minor boy gets horrific death sentence because of woman’s love affair), said another breathless headline from Haridwar.

We ate bhindi ki sabzi and puris and felt very sleepy. Sometime around 1 am, I woke up after feeling a throbbing pain in my leg, as if I was being hit. And I lost all sleepiness after seeing my sister in the room in the dead of the night, holding a hammer

Siddharth Rajput, brother of murder-accused Kannauj teenager

Khabar Lahariya describes prem prasangs as “salacious pieces of non-news” that capture relationships outside the conventional and incite instant media “salivation” and frenzy. And it’s almost always the woman who bears the brunt—“seared and scarred forever. Branded for life. If she survives.”

But the sansani (sensationalist) headlines hint at something deeper—a churning among rural youth caught between a desire for sexual freedom and a society that isn’t ready for it. Smartphones are stoking secret romances, and behind these stories, women are pushing back against circumscribed ideas of family, morality, and social convention.

“Love affairs and our intimate lives encapsulate all the messy social changes in any country. Romances are sites of resistance,” said Shrayana Bhattacharya, economist and author of Desperately Seeking Shahrukh: India’s Lonely Young Women & the Search for Intimacy and Independence.

But in rural India, this is manifesting in increasingly grisly ways. The last couple of months alone saw a litany of such cases.

In UP’s Farrukhabad, a woman called Alka hired a hitman to kill her 17-year-old daughter for carrying on a phone romance. The twist—the hitman turned out to be the daughter’s boyfriend and killed Alka instead. In Kaushambi, a woman poisoned her husband just moments after finishing her Karva Chauth fast, suspecting him of infidelity. In Bihar’s Motihari, an interfaith “missed call” romance turned fatal when a married woman and her lover crushed her husband’s skull with a stone. And in Jabalpur, echoing the Kannauj case, a 15-year-old girl and her boyfriend allegedly butchered her father and younger brother. The boyfriend reportedly flaunted five skull tattoos—each representing an intended victim.

Across the Hindi heartland, it’s a macabre descent into a youthful crimeland, with a quiet-desperation-to-mayhem trajectory that feels ripped straight from an OTT series.

These rising reports on violent love affairs may reveal deeper societal tensions, according to criminologist Ntasha Bhardwaj, whose research focuses on the impact of gender in crime.

“How do you define ‘love crimes’?” she said. “Our country is through a lot of religious strife, interfaith marriages being criminalised. So maybe because of that, there may be a lot more reports coming out. These reports can also be seen as a way to discourage people from live-in relationships, or affairs.”

Namra Izhar, a Delhi-based psychologist who works with juvenile offenders, links these stories of love and violence to a lack of support systems and a sense of “loss of control,” particularly in rural areas.

Also Read: Bengaluru is fast losing ‘safe for women’ tag—live-in murders, anxious parents, growing fear

Love or vengeance?

On the night of 21 May 2024, a Kannauj teenager allegedly drugged her family, murdered her father, and attacked her brother with a hammer. What’s still unclear is why.

As soon as the case broke, local Hindi dailies were quick to run dramatic headlines: ‘Papa ki pari bani unki hi kaatil’ (Father’s angel becomes his killer), reported Amar Ujala. ‘Premi ke liye jallad bani beti, aadhi raat ko utaara pita ko maut ke ghat’ (Daughter turns executioner for her lover, takes her father to the valley of death at midnight), said Jagran.

But back in Chhibramau, the family has more questions than answers. And the police findings haven’t aligned with the media verdicts.

“The news said she was involved with a Yadav boy. Everyone in Kannauj kept calling it a prem-prasang ka maamla, but somehow we as her family were in the dark,” said 40-year-old Moni. “How is this possible?”

The murder happened late into the night. The Kannauj teenager’s elder brother, 19-year-old Siddharth, said in his police statement that he woke to find his sister holding a hammer. He somehow fended her off and ran to alert the family. That’s when they discovered patriarch Ajay Pal Rajput lying on a blood-soaked cot.

“We ate bhindi ki sabzi and puris and felt very sleepy,” Siddharth told ThePrint, recounting the night in an almost nonchalant manner. “Sometime around 1 am, I woke up after feeling a throbbing pain in my leg, as if I was being hit. And I lost all sleepiness after seeing my sister in the room in the dead of the night, holding a hammer. I cried out to my mother and my younger brother Aman. When Aman went to call for our father, he found his body lying in that condition.”

The police and forensics team swooped in that night and the teenager was taken into custody. Police officials told ThePrint she confessed to killing her father, but insisted she acted alone, pleading for her 17-year-old ‘boyfriend’ to be spared.

Nevertheless, the boy—who lived across the road and studied at the same school as her—was named as a co-accused. The chargesheet alleges that he supplied the girl with chloroform and sleeping pills. Village gossip also focused on the supposed romance between the two. The girl’s family, from the OBC Lodh Rajput community, were relatively affluent, with her father working as a village development officer, while the boy’s Yadav family worked in cattle-rearing and farming.

Yet, the police found no hard evidence of a romance. No WhatsApp messages, no calls, no social media interactions. The only clue was the boy’s Google search history.

She wanted to kill her brother Siddharth, but to do so, she needed to make the rest of the family unconscious first. Maybe the sedatives wore off, and her father woke up or sensed something was wrong. That’s when she targeted him first, to ensure she could then kill her brother. That’s what she confessed to us as well

-handra Prakash Tiwari, secondary SHO of Chhibramau police station

“It has overtones of a love story, but the girl’s admissions make it seem as if it was more about taking vengeance,” said Chandra Prakash Tiwari, secondary SHO of Chhibramau police station and part of the investigation. “The only incriminating thing on the boy’s phone was his Google search history, which showed that he was looking up the effects of sleeping pills and where to buy them.”

While villagers and the media continue to say the murder had a romantic angle, the police were in a hurry to wrap up the case and dismiss it as sibling rivalry toward her elder brother Siddharth.

In a video filmed at the police station, she confessed to as much, and the final police report cites her anger over her parents supposedly favouring him as the likely motive.

“She wanted to kill her brother Siddharth, but to do so, she needed to make the rest of the family unconscious first. Maybe the sedatives wore off, and her father woke up or sensed something was wrong. That’s when she targeted him first, to ensure she could then kill her brother. That’s what she confessed to us as well,” Tiwari said, adding that the trial, set for October 2024, will clarify the events of that night.

But whatever the apparent motives, deeper psychological patterns often underlie such crimes, according to Namra Izhar, a Delhi-based psychologist who works with juvenile offenders.

She links these stories of love and violence to a lack of support systems and a sense of “loss of control,” particularly in rural areas.

“I was recently conducting a workshop with juvenile offenders, where one boy said that he would shoot someone down. He’s spent time in prison and there’s a lot of agony in him. This comes from a lack of outlets to channelise emotions. There are mostly negative coping mechanisms, particularly when one hasn’t had much exposure,” she said.

Izhar also points to the gender dynamics often at play. For men, it’s typically about ownership—“ladki meri hi hai” (the girl is mine). But for women, it’s more about regaining control and retaliating against the violence, stigma, and suffocating traditions imposed by their families—even if the results are messy, tragic, and violent.

Prem prasang coverage in Hindi media adds its own spin. Love itself becomes a villain, corrupting women and leading them down the path of violence, whether as victims or perpetrators.

Crime as entertainment

The love and murder combo has captured the Hindi heartland’s imagination for decades. Earlier, pulpy crime novellas sold at railway station bookstalls fed this appetite for scandal. Now, it’s true crime shows, YouTube channels, and Hindi news stories.

TV shows like Savdhaan India and Crime Patrol are increasingly focused on rural romances gone rogue, with prem prasangs from Bihar to Maharashtra’s Bhandara region serving as inspiration. True crime YouTubers like Prakhar True Crime and Usman Saifi Safar pull in hundreds of thousands of views.

Movies, too, have embraced the theme. Love-and-murder thriller Haseen Dilruba, starring Taapsee Pannu as a small-town femme fatale, was Netflix’s top film in 2021. This year, it even got a sequel, Phir Aayi Haseen Dilruba.

But when real-world cases are treated as entertainment before they even reach trial, the fallout is serious. Studies show this kind of media coverage can influence witness testimony, skew public perception, and even affect legal outcomes. It blurs the line between fact and fiction.

When women are involved, the media’s coverage typically casts them to one of three roles: “mad,” “bad,” or “sad,” as a 2015 paper in the Women’s Studies International Forum put it. This reductionist reporting, it noted, often glosses over deeper social causes, preventing any real understanding of such crimes.

Prem prasang coverage in Hindi media adds its own spin. Women are framed as deviants from ‘true’ womanhood—nurturing, caring, submissive. Love itself becomes a villain, corrupting women and leading them down the path of violence, whether as victims or perpetrators.

If we just write ‘girl accused of killing father’ as opposed to ‘girl conspired with her lover to kill her father’, they will think we are biased towards the woman’s family

-Vijay Singh, Kannauj-based journalist

And that’s exactly what sells, according to Vijay Singh, a correspondent for Dainik Jagran in Kannauj.

“Local readers pay close attention to words that evoke emotion. If we just write ‘girl accused of killing father’ as opposed to ‘girl conspired with her lover to kill her father’, they will think we are biased towards the woman’s family,” he said.

If a newspaper takes a dry, factual approach, Singh added, readers will say “chhodo inko” (leave them be).

“People won’t read our paper and might go to Amar Ujala or whoever else instead. There’s a lot of pressure on us from editors,” he said

However, Singh, a journalist since 2005, added that he has noticed a change: since 2015 or 2016, prem prasang stories have shifted from rarity to routine in Hindi dailies.

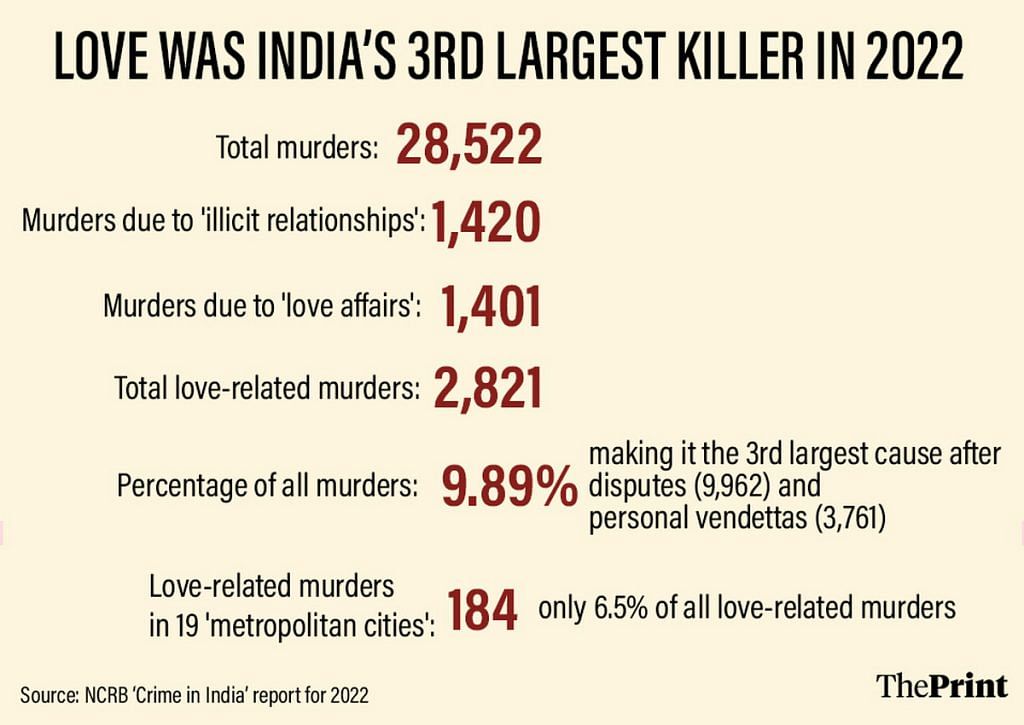

The crime stats also reflect an increase in such crimes. Between 2010 and 2014, “illicit relationships” and “love affairs” were the motive for 7-8 per cent of all killings, according to National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data. But since 2016, that figure has hovered around 10-11 per cent—meaning that at least 1 in 10 murders are tied to love gone bad.

Notably, the uptick in love-related murders comes at a time when the overall murder rate has been declining steadily in India, reaching its lowest since 1963 in 2022.

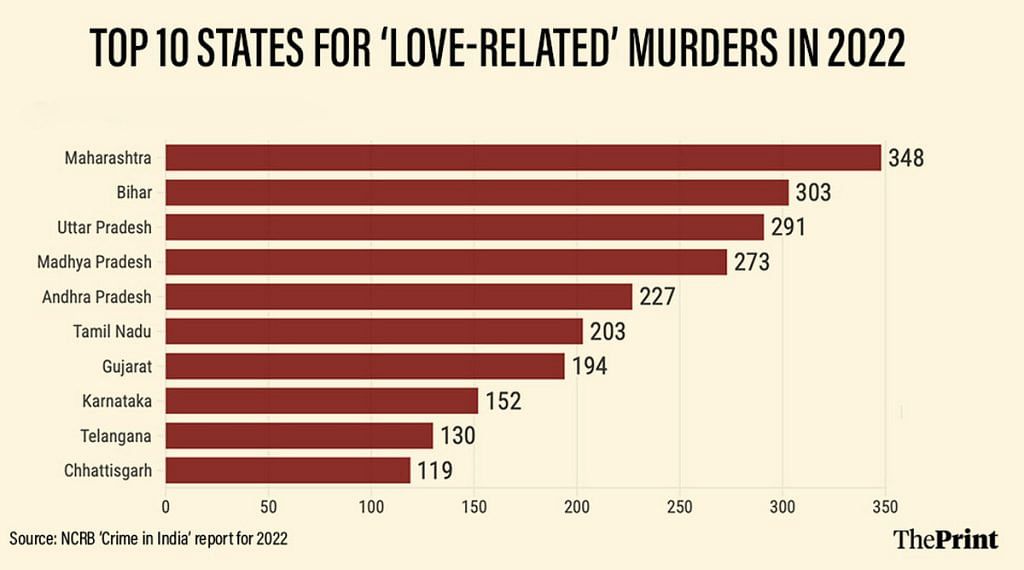

The latest NCRB report, released last year, shows that such cases numbered 2,821 in 2022, making them the third most common cause of murder in India. Of these, only 6 per cent were reported in the 19 ‘metropolitan cities’ listed by the NCRB, suggesting a concentration in small towns and rural areas.

However, Dr Parul Bhandari, a sociologist at the University of Cambridge specialising in the study of class, gender, and family, cautions against “exoticising” rural crimes.

“Honour and caste killings, as well as violence in general have existed forever. Children have killed their parents. It’s only that the medium is different, and a bigger group of people are now hearing or seeing about it,” she said.

Rather than reflecting “any assertion of youth agency in rural India,” she said the wave of grisly reports from villages reflects a growing interest in these places.

“There has been a general turn in pop culture since the late 2000s towards focusing on smaller cities and towns, especially since Gangs of Wasseypur. There is a general interest in life outside our urban bubbles,” she said.

Still, compared to more typical cases of interfaith romance, honour killings, or vengeful jilted lovers, the Kannauj teenager’s case stands out. A daughter killing her father is not the stuff of daily news and the entire village is still struggling to make sense of it.

Village verdicts—and silence

Despite the Kannauj teenager’s confession that she killed her father alone, many in her village aren’t convinced. Their disbelief falls into two camps—some think she couldn’t have done it without pernicious male influence, while others doubt she did it at all.

Ashish Dwivedi, who runs a stationery kiosk across from the school where the Kannauj teenager and her ‘boyfriend’ studied, is certain the 16-year-old deserves punishment—but he doesn’t hold her fully accountable.

“She must be punished. Tomorrow, what if some other girl reads or hears about this and thinks she can do the same to her family? But I also don’t think this was her own doing. Can a girl do this to her own father, unless there was some influence from outside? That boy must have brainwashed her,” he said.

Dwivedi recalls selling stationery to the teen and how the empty godown behind his shop was a hangout spot for schoolgirls waiting for their tuitions to start. He also blames mobile phones for lubricating illicit romances—though he admits the girl never carried one.

Even her mother Moni stressed that the 16-year-old didn’t have her own device. In fact, across the village of Karmulla Pur, none of the young women ThePrint spoke with had their own phones.

“Her father had his own phone, and we shared a family phone,” Moni said. “She would watch shows like Anupamaa or YouTube videos on it. Sometimes she’d look at cooking videos or comedic reels. If she’d been talking to this boy, I would have known.”

She liked listening to English music. And she had a babydoll haircut. Here, girls don’t usually go to parlours until after college or marriage. But she loved it. She could afford it

-Neha, friend of accused Kannauj teenager

But even as the teenager’s mother and uncle, Shivram Singh, described her life as monotonous and simple, her friends Bittu, Anchal, and Neha present a more complex picture.

“She didn’t have her own phone, none of us do. But she would meet Harish in between classes. Sometimes, they would bunk coaching classes after school and go to Chhibramau, which is a proper town—he would go on his cycle and she would take the tempo separately,” said Anchal.

The three friends have known the accused teenage girl since 9th grade. They recounted her love for Bigg Boss, her fondness for food, and how much she enjoyed treating her friends.

“She liked listening to English music. I don’t know the names of the songs, but it was all in English. And she had a babydoll haircut,” Neha added. “Here, girls don’t usually go to parlours until after college or marriage. But she loved it. She could afford it.”

Though the 16-year-old was studying to take up a course in the medical field, her real dream, they said, was modelling.

“She operated Instagram very briefly but then closed her account. She would always tell us she wants to do modelling. Woh toh uske saamne thoda nikamma sa lagta tha (the boy looked like a goofball in front of her),” Anchal said. “He once came to our class to hand a textbook and he was very polite to us. He knew we were her friends.”

The girls reject the version of events given by the 16-year-old’s family, but they find it “nowhere imaginable” that she could kill her father.

Meanwhile, in their shanty in Karmulla Pur, the Kannauj boy’s father Pramod Yadav, and his two older sisters showed off his weathered javelin-throwing medals. They described him as an “intelligent boy” who narrowly missed getting into Navodaya Vidyalaya.

His family members insisted he had nothing to do with the crime and that the girl acted alone.

Yet, from Moni to the villagers, no one seems willing to confront the deeper family dynamics. Or the police’s claim that the real target was the girl’s elder brother Siddharth.

The only hint that something might have been amiss at home came from the teenage girl’s friends, Neha and Bittu Thakur, who mentioned she rarely spoke about Siddharth.

“We didn’t even know she had an older brother until we saw him once at her house,” Neha said.

Often, it’s not just the facts of a ‘prem prasang’ case that are scrutinised—it’s the ‘character’ and ‘reputation’ of both the killer and victim.

Muzaffarnagar Valentine

A love story spiralled into even bloodier territory in Muzaffarnagar’s Phulat village—a revenge-driven showdown that left four people dead.

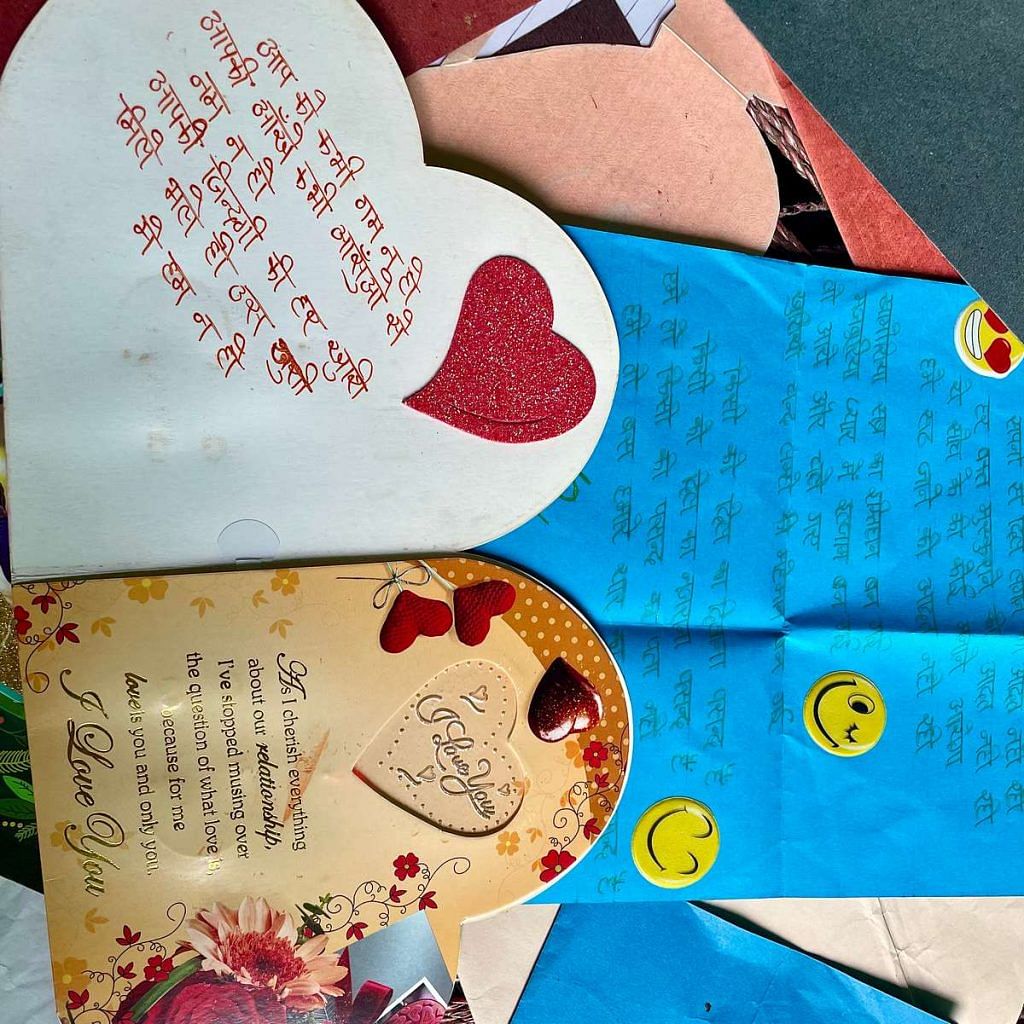

At her ramshackle house in Phulat, 49-year-old Sunita Devi leafed through a stack of love letters written in neat Hindi, covered in hearts and smiley stickers—all addressed to her son Ankit from his neighbour Karuna. The collection also includes cards with red roses, as well as Holi and Valentine’s greetings.

This love affair didn’t just cost Sunita her 27-year-old son. It started a chain reaction of violence that wiped out three other lives and left at least six people behind bars.

“If my son coerced her and made her run away, what do all these letters show?” Sunita asked, flipping through the colourful notes. “She was clearly in love with him too. She would sneak into our house to drop off these letters.”

One of these letters dripped poetic affection: “Aapke deedar se nikalte hai taare, aapki khushboo se chahakti hai bahaare. Aapke paas hai aisi nazarein, chhip-chhipkar chaand bhi aapko nihaare. Good Night” (The stars shine at the sight of you, spring chirps from your fragrance. You possess such a gaze, even the moon slyly glances at you).

Even now, my mother doesn’t have any remorse. She doesn’t even consider me her child. Her sons were her only children. My father and brothers weren’t talking to me but they were not so hellbent on vengeance as my mother was

-Karuna, wife of murder victim Ankit

In another, she urges Ankit to meet her “for just 5 minutes” outside her school’s main gate, eager to introduce him to her friend. One note asked Ankit to meet her at 5 in the morning, urging caution since she wasn’t sure where her brother would be. This letter, like many others, signed off with an “I.L.U.”—short for ‘I love you’.

Ankit and Karuna, now 23, both belonged to the Ravidassia Dalit community, but Karuna’s family forbade the relationship—marrying someone from the same village was a violation of tradition. When the love letters weren’t enough, the couple eloped in March 2023 and fled to Meerut.

But Ankit missed home. He would often return to Phulat to visit his family. During one such trip, on the evening of 27 February, Karuna’s brothers, Rohit and Rahul, accosted Ankit and attacked him with a blade. He died on the spot. That wasn’t the end. When Ankit’s family got the news, his father and three brothers rushed over. A gunfight followed, killing both of Karuna’s brothers and her father.

Now, Karuna is in hiding in Meerut, living with one of Ankit’s relatives. She’s left with nothing but grief and regret.

“My mother and the only brother left alive are in jail (for criminal conspiracy). My father is gone. The love of my life is dead. I can’t go back to the village because everyone is baying for my blood when all I did was choose to love a man of my choice,” Karuna said, choking back tears as she sat at a dhaba on the Meerut highway. None of this would’ve happened if my family just accepted our love and marriage. Why did they have to go after him?”

Like the Kannauj teenager, Karuna expressed a sense of being an outsider within her own family. Her brothers were favoured, she claimed, and her family never acted out of concern for her.

Murder, moral codes, mothers

In Phulat, the prevailing sentiment is that Ankit and Karuna played with fire and got burned. For many, breaking tradition comes with consequences.

“We kept warning Ankit not to come back, but his friends encouraged him. He paid the price,” said Prem Pal, 55, the former pradhan of the village. He added that while honour killings had been heard of, this was the first time the village had seen violence on this scale.

Even Ankit’s friends blame the couple, seeing the bloodshed as their own doing.

“What Ankit did was wrong, and we simply can’t support it,” said 25-year-old Abhishek, a friend and neighbour.

Prem prasang has a different meaning from honour killings. More than fathers, usually it is the brothers and uncles or chacha-taus who are often more aggravated against the child or couple, because it is not their own direct bloodline

-Atul Chaubey, additional SP of Muzaffarnagar

For him, this was about breaking social codes, especially marrying a girl from the same village. Karuna said the couple chose an Arya Samaj ceremony, but everyone in the village calls it a ‘court marriage’— another no-no.

“Everyone in the village is like family. You can’t marry a girl of your caste from the same village. Why couldn’t he find someone from another village?” Abhishek said. “The violence was wrong , but what Ankit did was also wrong, no? How can you have a court marriage without the parents’ approval?”

Atul Chaubey, additional SP of Muzaffarnagar, told ThePrint that the dynamics of some prem prasang murders at the hands of family members differ subtly from typical honour killings, where fathers are usually the enforcers of the family’s reputation.

“Prem prasang has a different meaning from honour killings. More than fathers, usually it is the brothers and uncles or chacha-taus who are often more aggravated against the child or couple, because it is not their own direct bloodline,” he said.

However, Karuna’s aunt, 32-year-old Sonia Devi, insists her family want her back and had no intention of hurting Ankit.

“If we had to harm him or do anything to them, we would’ve taken action much earlier. They had been together for a while, why is it that this happened only this February? Our family didn’t do anything,” she said.

Karuna, though, is sceptical about her family’s intentions. She points out that they never reported her elopement to the police or filed a case of kidnapping.

“If they were so concerned about me, why didn’t they come search for me? I had run away from home on 28 March last year, pretending to go for an exam. They never came searching for me. If they didn’t even bother to look for me, why did they target him?”

Love affairs and our intimate lives encapsulate all the messy social changes in any country. Romances are sites of resistance

-Shrayana Bhattacharya, economist and author

Like the Kannauj teenager, Karuna expressed a sense of being an outsider within her own family. Her brothers were favoured, she claimed, and she’s especially bitter toward her mother, now in jail.

“Even now, my mother doesn’t have any remorse. She doesn’t even consider me her child. Her sons were her only children,” Karuna said. “My father and brothers weren’t talking to me but they were not so hellbent on vengeance as my mother was. Mothers are such that they express pain even at the hurt of another’s child, but my mother is nothing like that.”

Today, the small salon where Ankit worked as a hairdresser is locked up. His father and brothers, who ran small shops selling mobile accessories and groceries, are all in jail.

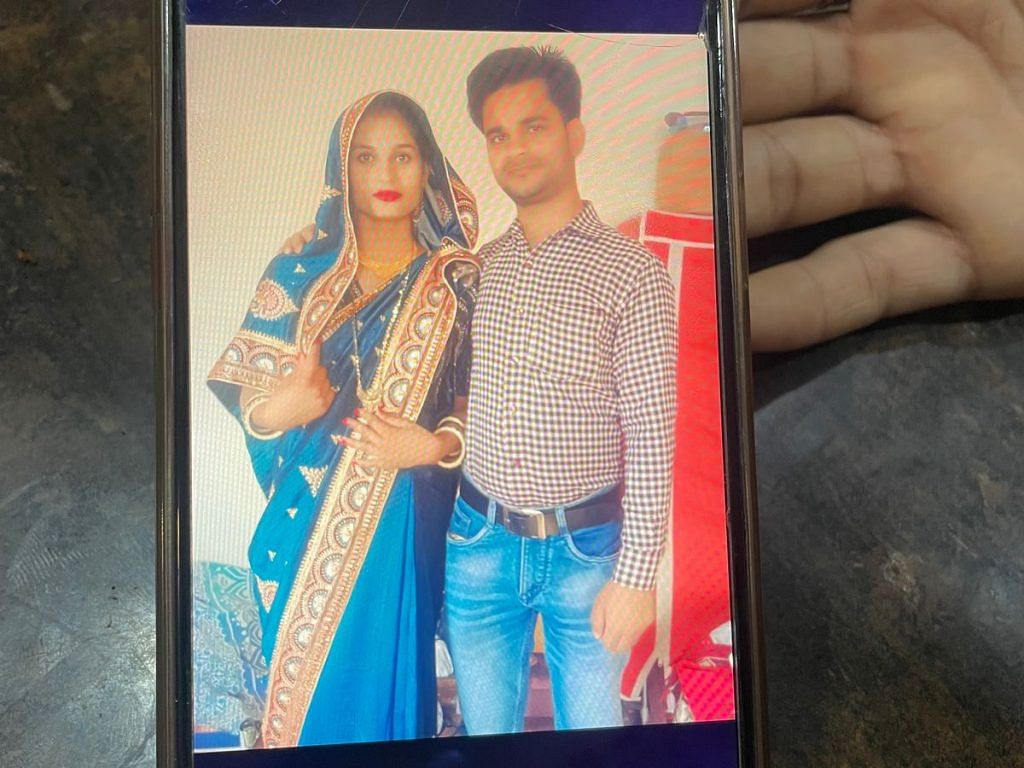

Meanwhile, Karuna has dropped out of her nursing programme and is haunted by memories. Her WhatsApp profile still shows her beaming with her husband by her side, her scarlet lipstick matching her fresh sindoor.

She recalled her birthday on 25 February, two days before Ankit was murdered.

“He bought me Banarasi saris and bangles on my birthday. He treated me like a princess,” she said. “I couldn’t have imagined that the light of my life would be gone forever just after celebrating my birthday.”

If killer Adnan is a self-professed khalnayak, victim Asma is a khalnayika (villainess) in the eyes of some Khurja residents.

‘Khalnayak’ in love

In June 2024, a grisly discovery was made at a qabristan in Khurja, Bulandshahr. A woman in a burqa lay near the graves, her throat slashed and stab wounds on her body. But before the investigation could fully begin, whispers about her alleged extramarital affair overshadowed the crime itself. As often happens, the case became less about justice and more about titillation.

The victim, 36-year-old Asma, lived with her husband Saleem and their three sons in Khurja’s Nayi Basti locality. Three years ago, a young man named Adnan moved into the building’s upper floor. Saleem worked as a roti-maker and helper at multiple hotels, while Adnan picked up various odd jobs.

Rumours had long swirled about Asma and Adnan’s closeness, despite him calling her ‘sister’. But when 26-year-old Adnan was arrested, his explosive confession to the media left little room for doubt.

He claimed to be inspired by Sanjay Dutt’s character Ballu, the ‘villain with a heart of gold’ from Khalnayak.

“She betrayed me in love, and there’s only one punishment for betrayal – death. I cut her throat with a knife. She took away my 2.5 years’ worth of income, and fell in love with another man,” he told the media.

The investigating officer in the case, Ajay Kumar said that this video statement became the clincher piece of evidence and sped up the trial. On 27 August, Adnan was sentenced to life in prison by a fast-track court.

Khurja police officials told ThePrint that Adnan, who had a history of drug addiction, suspected that Asma was having another affair, this time with a man named Furqan. What reportedly sent Adnan over the edge was that Asma used a phone he had gifted her to speak to Furqan. Adnan and a friend then lured Asma to the cemetery—their old meeting spot—and murdered her.

In the Hindi media, Asma’s murder was quickly branded a gunaah (sin) committed by her premi (lover), with many reports focusing on the Khalnayak-inspired angle. Others speculated that Adnan and Asma were in a live-in relationship that ended in violence. Yet, as with many ’prem prasang’ murders, the truth remains murky.

Asma’s sister Reshma rejects the affair story outright.

“He coerced her into this relationship. It was not prem prasang or an affair, it was one-sided,” Reshma said. “Asma was going to report him to the police, that’s why he decided to slash her throat. He threatened her—‘tera gardan kaat dunga main’ (I’ll cut your throat).”

Reshma also dismissed claims that Asma had another lover, Furqan, claiming that her sister didn’t even own a smartphone.

Conflicting narratives are common in such cases.

“If the phrase ‘prem prasang’ (love-affair) is being thrown around in public you know something has gone wrong,” observed Kavita, editor-in-chief of Khabar Lahariya. “Prem prasangs happen outside the bounds of socially sanctioned, parentally approved, big dhoom dhaam se shaadi relationships.”

And often, it’s not just the facts of the case that are scrutinised—it’s the ‘character’ and ‘reputation’ of both the killer and victim.

Also Read: Rural Haryana is at war with love marriage—brother shoots sister, boasts on Instagram with gun

‘Buri aurat’

If killer Adnan is a self-professed khalnayak, victim Asma is a khalnayika (villainess) in the eyes of some Khurja residents.

Adnan’s family has squarely placed the blame on her, calling her a “buri aurat” (bad woman) who led their son astray.

“Our son wasn’t in the right mental state,” said Adnan’s father Sajid, a painter-plasterer. “He wouldn’t have done this by himself.”

Adnan’s younger sister Sahiba also blamed Asma, claiming she had manipulated her brother, got him hooked to drugs, and led him to ruin.

“She used to get him beaten up, she got him addicted to drugs. My brother became obsessed with her and she had him wrapped around her finger. He brought a phone for her with his money. He would spoil and pamper her. Woh aurat theek nahi thi (that woman was not right),” she said.

In Sahiba’s view, Asma had brought the murder upon herself.

“Jo bhi hua, shayad theek hi hua (Whatever happened was perhaps for the best),” she said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Platforms such as AltBalaji (owned by the infamous Ekta Kapoor) and others must be banned. Every single show on these platforms is about illicit affairs and crimes related to such affairs. This is just a shameless soft porn industry operating in full public view.

Rural youth are addicted to such platforms and it puts ideas into their head. The age being impressionable, this leads to many such crimes.

The deep rooted patriarchy of the Hindi heartland is another serious obstacle. Maybe the schools can counter some of it through counselling sessions for teenagers.