Kannauj/New Delhi: Kannauj’s attar, Bhagalpur’s Jardalu mango, and Mysore silk all share a common pedigree: the much sought-after GI tag. Yet, their fate, sales, and demand have taken very different trajectories. Mysore silk, tagged in 2005, has been flying off the shelves. Jardalu mango has gone from local secret to international markets since being tagged in 2018. But Kannauj attar, certified in 2014, is still waiting for the sweet smell of success.

The Geographical Indication tag is a badge of honour, meant to signal quality and boost market appeal for one-of-a-kind hyper-local products. But the tale of three GI tags—from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Karnataka—shows it’s not always a golden ticket.

It’s been a decade since UP’s Kannauj attar got its unique tag, but many business owners in the 400-year-old perfume industry are yet to see the promised benefits. To get the GI tag in their hands, they have to get through that ubiquitous bureaucratic hurdle called an N-0-C, followed by the actual certification. They continue to struggle with older problems like high GST rates, shrinking markets, outdated practices, and raw material shortages. The GI tag, they are now realising, is no magic pill for business.

Gaurav Mehrotra, a third-generation perfumer, has been anxiously waiting for his GI certification to come through. He got his no-objection certificate, or NOC, as a local trader from the president of the Kannauj Attars and Perfumes Association two months ago. But now his GI application is stuck at the Geographical Indications Registry Intellectual Property Office in Chennai.

“We sell our products to a natural cosmetic company. Now every company has started asking for GI certification. So, we applied but have not received the certificate yet,” Mehrotra said.

The experience of the coveted GI tag, however, isn’t the same everywhere.

The fragrant Jardalu mango from Bihar’s Bhagalpur has been riding high since earning its tag six years ago. National demand is growing and it was exported for the first time in 2021. In Karnataka, the GI tag has increased demand for Mysore silk so much that supply can’t keep up. The Karnataka Silk Industries Corporation (KSIC) says the tag has also attracted more foreign buyers.

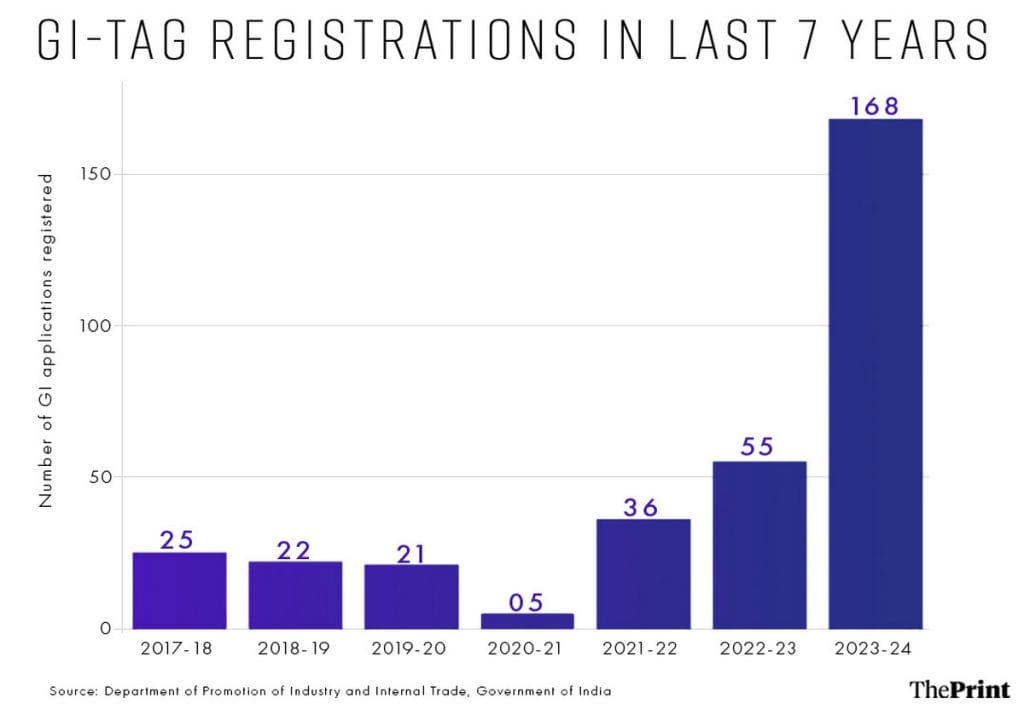

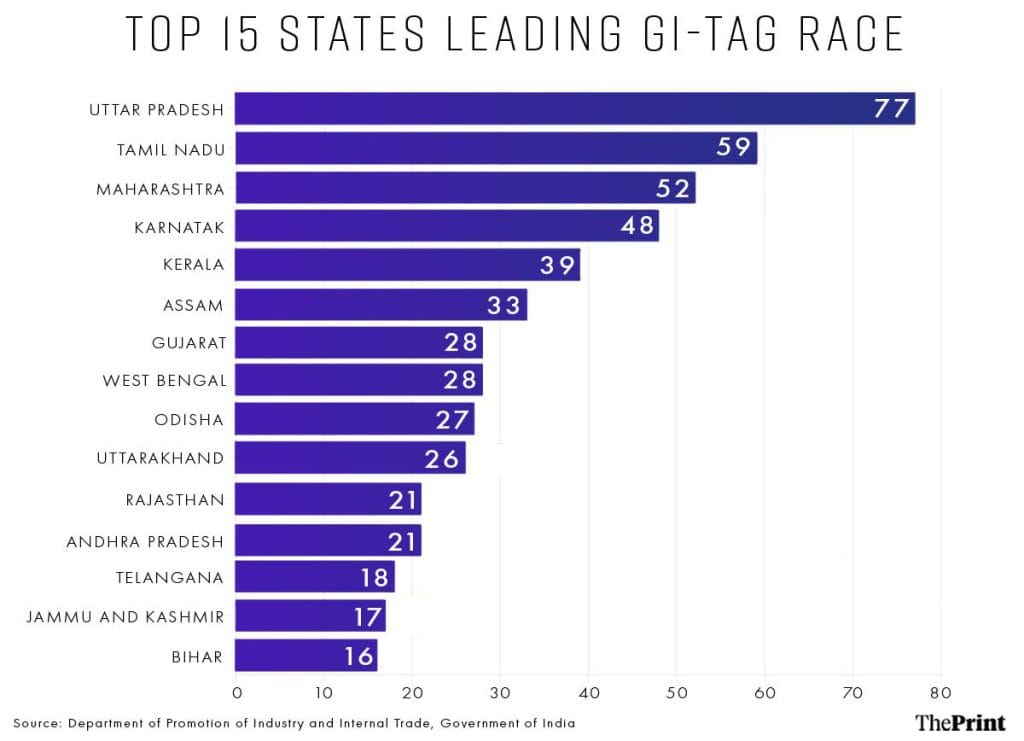

In the last two decades, 643 products in India have received the GI tag, covering traditional regional specialties in agricultural produce, textiles, foodstuffs, and handicrafts. The list includes Darjeeling tea, Kota Doria fabric, Coorg orange, Madhubani paintings, Banaras thandai, and Kashmir pashmina. The pace has picked up in the last seven years, with 332 tags awarded in that period alone. In 2023-24, 168 products got this tag.

“Our GI-tagged local products are a class apart. They not only represent our unique history and knowledge but also support lakhs of people who painstakingly work to preserve them,” said Piyush Goyal, Union Minister of Commerce & Industry in a tweet this June.

The same month, during the Mann Ki Baat radio show, Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke glowingly of Araku coffee from Andhra Pradesh, which was awarded the GI tag in 2019. “When we see a local product from India going global, it is natural to feel proud,” Modi said.

But there’s many a slip between the cup and the lip.

Obtaining a GI tag can be a lengthy process, often taking several years due to the need for historical evidence. For instance, it took five years for Kannauj attar to collect the necessary documentation to prove its origins. For Mithila makhana, the wait was four years until it finally got its tag in 2022.

Even after that it’s not necessarily smooth sailing. While the registration process is “very complicated”, the real trouble begins later, according to Dr Mohit Sharma, assistant professor at the School of Agribusiness and Rural Management, Dr Rajendra Prasad Agricultural University, Pusa, Samastipur.

“There is a race to get a GI tag in India, but no one is paying attention to the post-GI registration mechanism. Before getting a GI tag, market acceptability has to be studied, and for this, a market channel needs to be created,” Sharma said.

Currently, the GI tag is seen as a goal in itself without a matching push at the level of producers to ensure good manufacturing practices and world-class quality, he added.

“There is an institutional lacuna,” Sharma said. “An institutional framework must be created to take full advantage of the tag and for this awareness programmes are needed.”

While some products gain a GI tag but not much traction, Bhagalpur’s Jardalu mango has rocketed to fame in Bihar and beyond.

Also Read: Fighting over Tangail saree GI tag won’t do India-Bangladesh any good. It’s a shared legacy

The GI punch to Jardalu

There are some industries that have taken the GI tag and added new heft. The Jardalu mango from Bihar’s Bhagalpur is a prime example.

In June, 26-year-old Santosh Kumar trekked 25 km from Fatuha to Patna for the Mango Festival at Gyan Bhawan. He’d heard tales of the Jardalu’s glory and just had to taste it himself.

As soon as he arrived, Kumar made a beeline for the Bhagalpur Jardalu stall. There, mango farmer Rakesh Singh regaled customers about how the aromatic, saffron-tinged variety had been granted a GI tag because it was only grown in the fertile plains of Bhagalpur. The story goes that the mango just won’t have the same fragrance if it’s grown anywhere else.

Mango lover Kumar was not disappointed.

“Last year, I heard about this mango for the first time and since then I wanted to see and taste it. So, I went to the festival this year and bought some mangoes. Each bite releases a burst of flavours,” he said.

After the GI tag, the world has started knowing about (Jardalu) mango. Where there was nothing earlier, something has happened. Exposure has been given by the state government and packaging has been encouraged, which has also increased the income of the growers.

-Randhir Choudhary, Bihar Mango Growers’ Federation

The mangoes sold out quickly, and saplings worth Rs 11 lakh vanished on the first day alone.

While some products gain a GI tag but not much traction, the Jardalu mango has rocketed to fame in Bihar and beyond.

In 2020, the Bihar Postal Department even issued a special stamp featuring it, and the state promotes it as the king of fruits, with every poster and social media post flaunting its GI tag.

Summer might be scorching all around but in Bihar summer is very tempting. Comment the name of your favorite Mango variety.

.

.

.#mangoseason #summer #mango #summervibes #favoritefruit #bihartourism #BiharTourism

.

.

.@incredibleindia @tourismgoi @AbhaySinghIAS pic.twitter.com/samT5KTwfs

— Bihar Tourism (@TourismBiharGov) May 10, 2024

But earning the GI tag wasn’t easy. Few outside Bhagalpur knew about the mango’s delights. It took nearly a decade of dedication from Ashok Choudhary, the Bhagalpur Mango Federation’s president, known as the Mango Man of Bihar. He sent mangoes from his orchard to VIPs, engaged with government officials, and wrestled with extensive paperwork. When the GI tag was finally granted in 2018, the state and district administrations ramped up efforts to promote cultivation and packaging, slowly stirring up nationwide demand.

“To increase awareness, this mango was sent every year to the President, Prime Minister, MPs, and special guests. This increased awareness at the pan-India level,” said Randhir Choudhary of Bihar Mango Growers’ Federation. “After getting the GI tag, Jardalu got a lot of publicity and now its demand is increasing.”

While Choudhary hopes for more government subsidies, he’s pleased with the tangible changes brought by Jardalu’s new status.

“After the GI tag, the world has started knowing about this mango. Where there was nothing earlier, something has happened. Exposure has been given by the state government and packaging has been encouraged, which has also increased the income of the growers. It is also displayed in the mango shows of Delhi, UP, and Patna.”

In 2021, GI-certified Jardalu mangoes made their international debut. First, they were part of a week-long mango promotion programme in Bahrain, where they took pride of place among two other GI-certified varieties— Khirsapati and Lakshmanbhog of West Bengal—at the superstores of importer Al Jazeera Group.

Then in June, the first batch was exported to the UK—a collective effort by the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA), the Bihar government, the Indian High Commission, and Invest India.

Between 2021 and 2023, APEDA, in collaboration with the state government, exported 4.5 lakh tonnes of organic Jardalu mangoes to Bahrain, Belgium, and the UK.

Jardalu plantations in Bhagalpur currently cover 750 hectares, with more farmers taking up its cultivation, according to the district horticulture department.

“In the past few years, both awareness and demand for this mango have increased,” said Abhay Kumar Mandal, assistant director of horticulture in Bhagalpur. He added that of the 100 mango saplings given to farmers by the department, 70 are of the Jardalu variety.

“Jardalu is a very early variety, ripening by May and early June. Its shelf life is short, and it’s sensitive to climatic conditions, making production variable every year. But growers see benefits in this fruit,” said Mandal.

Kannauj attar-makers complain of not seeing enough support and economic benefits after the GI tag. But the central government’s Fragrance & Flavour Development Centre (FFDC) argues better marketing and manufacturing processes need to come first.

A stink over perfume

Fourth-generation Kannauj perfumer Anoop Kelkar, 58, is a traditionalist. His business, Kelkar and Sons, still uses the age-old deg-bhapka (steam-distillation) technique to make natural attars with rose water and gulkand. Like many others in Kannauj, he uses cow dung cakes as fuel for the process. While his business is chugging along, Kelkar’s annual turnover has stagnated at Rs 1 crore for the past five years.

Kelkar recounted the optimism that came with the GI tag in 2014.

“We expected that with the tag, our exports would increase, but the excitement and interest faded over time,” he said, surrounded by colorful bottles of his fragrant creations. “Business is going on as it was before. There has been no increase due to the GI tag. We don’t even know how to use it.”

There is immense potential in the attar industry. In the last few years, the demand for natural products has increased rapidly across the world. But the attar industry has not yet properly utilised the GI tag

-Shakti Vinay Shukla, director, FFDC

–

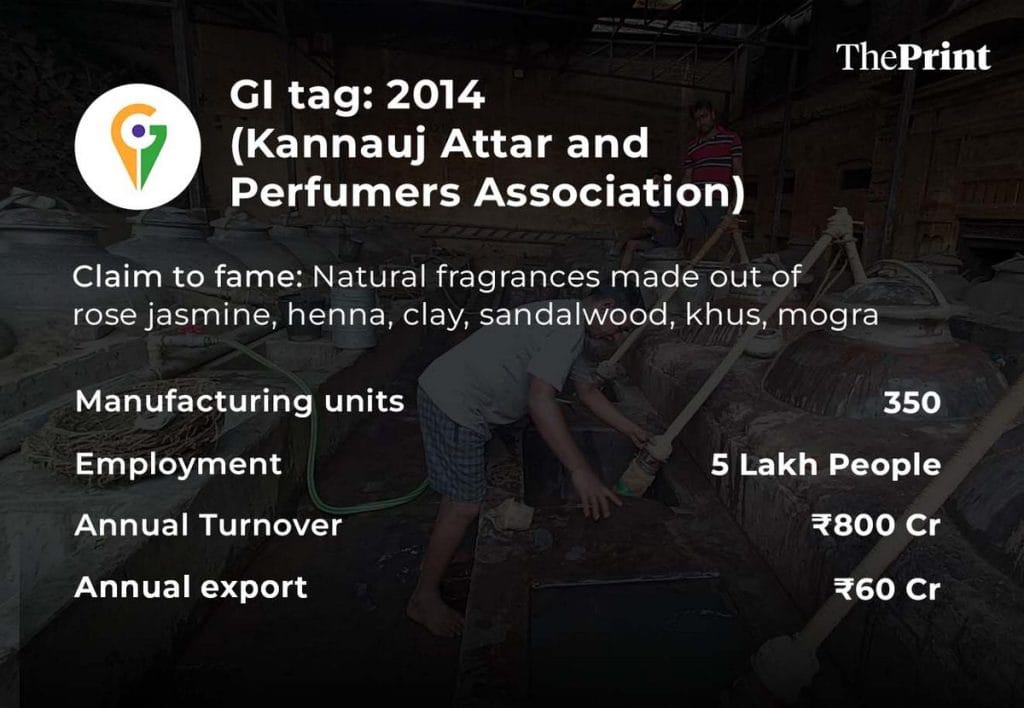

Legend has it that attar-making in Kannauj began in the early 17th century when Mughal empress Nur Jahan noticed the fragrant oils left behind by rose petals in her bath. Today, this legacy lives on through roughly 350 attar units, employing at least 5 lakh people. The industry has an annual turnover of Rs 800 crore, with Rs 60 crore coming from exports, according to District Industries Centre (DIC) officials.

In Kannauj’s Bada Bazar, the heart of the attar industry, narrow lanes are packed with perfumeries—some over 150 years old. Most shops are run by families who’ve been in the business for generations. Many still operate in a disorganised, old-fashioned way.

This resistance to change is a major reason why Kannauj has not been able to achieve a major market breakthrough despite its GI tag, according to Shakti Vinay Shukla, director of the Fragrance & Flavour Development Centre (FFDC)—a central government research centre set up in 1992 to help the attar industry.

“There is immense potential in the attar industry. In the last few years, the demand for natural products has increased rapidly across the world. But the attar industry has not yet properly utilised the GI tag,” Shukla said.

The FFDC played a crucial role in securing the GI tag for Kannauj attar after five years of effort, including tracing its history and clearing a maze of paperwork.

But now the tag has become a flashpoint. The attar makers complain of not seeing enough support and economic benefits, while the FFDC argues that the tag is a tool that’s not being used effectively through better marketing and manufacturing processes.

Sumit Tandon, who runs the 150-year-old Devi Prasad Sundar Lal Khatri perfumery in Bada Bazar, despairs about the industry’s future.

“I see this industry breathing its last. The way synthetic perfumes have dominated over natural perfumes in the last few decades has created a deep crisis,” he said.

Tandon reminisced about a time when even paanwalas and mithaiwalas used attar at their shops, but rued that rising costs and changing tastes have decimated the market.

Another major issue is the inaccessibility of sandalwood oil, the traditional base for attars. With sandalwood now priced at over Rs 90,000 per kg, it’s out of reach. Most traders have switched to cheaper, chemical alternatives like Dioctyl Phthalate (DOP), which affect quality.

“Only a few people make perfume from sandalwood, that too on special order,” said Rajeev Mehrotra who owns the over century-old Lala Kedarnath Khatri perfumers. Mehrotra doesn’t even know about the GI tag.

And then, there is GST—a major sore spot.

“Kannauj perfume has a GI tag and is considered special by the government. It should be tax-free, or at least have reduced GST on raw materials,” argued Pawan Trivedi, president of the Kannauj Attars and Perfumes Association. “So far, the government hasn’t supported the industry as it should.”

The industry has also called for the FFDC to research and develop a new base oil for attars.

However, the FFDC says that it submitted two proposals to the central government—one for research into a substitute base and another for new attar formulations— but was unable to get adequate funding.

“We are there to help the industry but they have to think about how to change, reevaluate, reproject themselves to compete with the world,” said FFDC’s Shukla. “The traders should come to us and ask for what they want but they just keep cursing us. This will not benefit them.”

While the FFDC doesn’t conduct formal training sessions, Shukla maintains that industry members are welcome to consult with the centre’s experts. According to him, the onus lies with the industry to take initiative and collaborate with the FFDC to overcome issues.

In an industry where commercial brand-building is rare, Praveen Tandon uses packaging and poetry to make his Boond range stand out.

A whiff of change

Not all perfumers are clinging to tradition. Some new-age attar entrepreneurs are carving out their own brands—a rarity in the industry—and leveraging the GI tag.

Praveen Tandon, a first-generation perfumer who launched his brand Boond in 2021, uses packaging and poetry to stand out.

Instead of the usual small vials, his attars come in sleek cylindrical bottles wrapped in cloth pouches, each paired with a handwritten poem. For Rakshabandhan, he created a special edition with a custom verse: “Yun to hai bandhan lekin par is dhaage me such hi such hai” (Though it is a bond, this thread is full of truth).

Perfumers like Tandon, who primarily sell online, prominently feature the Kannauj attar GI tag to signal authenticity.

“It’s not easy for us, but we’re making our mark through unique offerings and packaging,” he said.

Climate change has affected the availability of raw materials a lot. The perfume business depends on flowers, and this year’s production has been very low. Plus, there’s no policy to support flower farmers

Praveen Tandon, Kannauj perfumer

Following the 2014 GI tag, there was a push to revitalise the attar industry through the development of an attar park, but it’s still not complete. To increase its visibility, Kannauj attar was also presented to delegates at the G20 Summit last year. However, Tandon stresses that ultimately, the responsibility lies on industry players to build a market for their GI-tagged products.

“Most people here have been in the buyer-to-buyer model, but we focused on the buyer-to-consumer model, which is new for Kannauj. Branding is also a new concept in the attar market,” he said.

But the most pressing problem for him right now is a shortage of flowers to make attar. In June, the deg-bhapka vessels in his house lay idle for some 15 days because of this.

“Climate change has affected the availability of raw materials a lot. The perfume business depends on flowers, and this year’s production has been very low. Plus, there’s no policy to support flower farmers,” he said.

Many farmers in nearly 60 villages around Kannauj grow flowers and sell them to perfume merchants, but this year, the heat has wreaked havoc, and summer flowers like mehendi and jasmine were in short supply.

“This time, the cultivation of flowers is very low. Rose flowers were burning in many places,” said Ram Swaroop, a flower trader.

Senior Scientist Amar Singh from the Krishi Vigyan Kendra confirmed the impact: “The high temperature has affected the yield. Buds aren’t flowering, and the quality of flowers has also been affected. We estimate a 15-20 per cent decrease in yield.”

Sumit Tandon, who has 31 deg-bhapkas in his factory, used to buy 800-900 kg of jasmine daily. This year, he’s managed with just 400-500 kg.

Also Read: ‘Mango has to survive’— this juicy Delhi book launch was all about India’s favourite fruit

Mysore silk rush

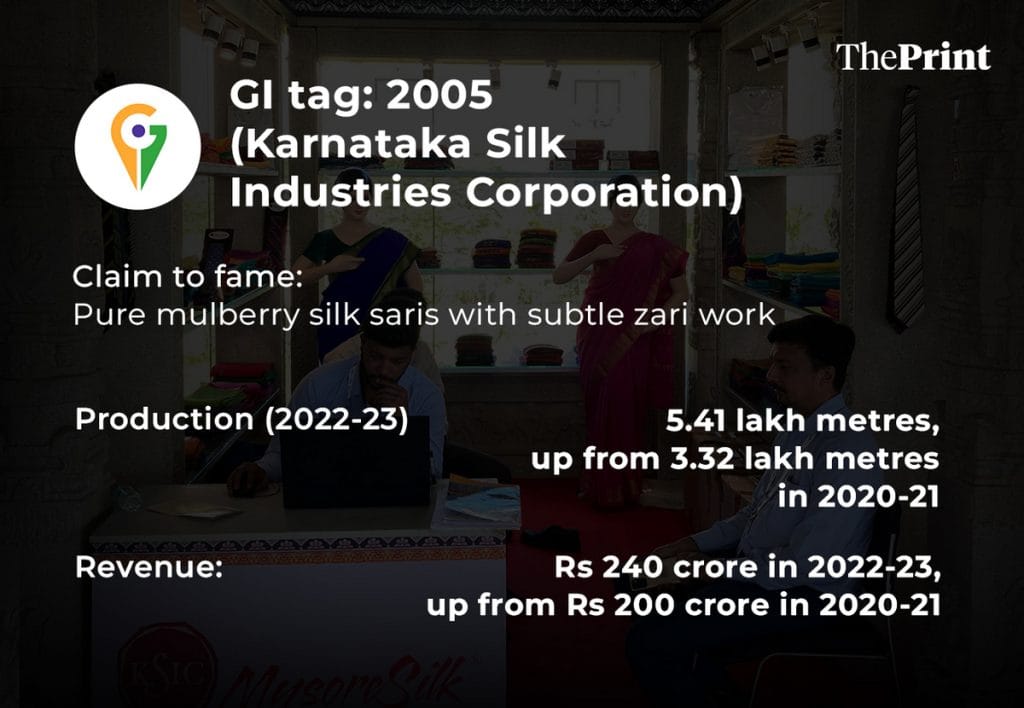

While Kannauj’s GI-tagged attar struggles to make its mark, over 2,000 kilometres away, Mysore silk is basking in the glow of its own GI success. Since earning its tag in 2005, Mysore silk has only grown stronger in reputation and demand. In fact, the biggest challenge now is keeping up with that demand.

Saris made from this rich, lustrous fabric, woven from pure mulberry silk and featuring subtle zari work, are being snapped up faster than the state-owned Karnataka Silk Industries Corporation Limited (KSIC) can produce them.

Last year, Karnataka Minister of Sericulture and Animal Husbandry K Venkatesh urged KSIC to double production. In response, the KSIC managing director pointed out just how much production had grown. From 3.32 lakh metres in 2020-21, production increased to 5.41 lakh metres in 2022-23, boosting revenue from Rs 200 crore to Rs 240 crore. To top it off, the total Mysore silk produced in the entire previous decade, 2012-2022, was only 4.5 lakh metres.

The GI tag helps in publicity and promoting the heritage of Mysore Silk. In the last few years, its demand has increased. Even though the price has increased by around 15 per cent as the gold and silver prices have risen, it’s still a craze among women

-Senior KSIC official

But it’s still not enough. Vigorous promotion of the GI tag has turned these saris into a hot commodity, but a shortage of master weavers means some looms are gathering dust. Even with efforts to crank up production, the lack of skilled hands is making it tough to keep shelves stocked, leaving customers scrambling for their favourite colours and designs before someone else grabs them.

KSIC officials told ThePrint that between 2021-22 and 2022-23, silk fabric sales increased by Rs 41.08 crore in value terms.

“The GI tag helps in publicity and promoting the heritage of Mysore Silk. In the last few years, its demand has increased. Even though the price has increased by around 15 per cent as the gold and silver prices have risen, it’s still a craze among women,” said a senior KSIC official.

The silk’s allure isn’t limited to India. It’s currently exported to 16 countries, with several—including Germany, Australia, and Singapore—being added to the list after the GI tag. The US accounts for 61.14 per cent of the exports and Germany 30.77 per cent, according to KSIC officials.

Perumal, 48, has run a silk shop in Bangalore for the last 25 years. And thanks largely to his Mysore silk stocks, business has been booming, with customers from both India and abroad flocking to his shop.

“Foreign customers are more excited about GI-tagged products. They give more importance to it. Many times, they ask about the product and seek information about when it was given the GI tag,” he said. “The tag has given global recognition to this market.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)