Bengaluru: On a Monday afternoon, Bengaluru-based Chetan Krishna, 32, took time off from preparing for the civil services exams to post a video of a Korean influencer speaking in Kannada to an elderly woman. “Koreans are putting effort to learn and speak with the native Kannadigas. But our Indians are refusing to speak basic Kannada in Karnataka…” he posted on X. About 100 km away, in Maddur, Karnataka’s Mandya district, 36-year-old farmer and businessman, B. Mallikarjuna reposted it.

This is part of a ‘new language war’, much like the Tamil-Hindi battle playing out in Tamil Nadu.

Krishna and Mallikarjuna are part of a growing army of ‘digital guardians’. They are not members of pro-Kannada groups like the Karnataka Rakshana Vedike (KRV) but are on the same page when it comes to the Kannada language and the imposition of Hindi. Now, as the government of India gets ready to mark Hindi Diwas on 14 September, their voices have become more strident, lending support to pro-Kannada groups that have planned protest marches on Saturday.

“We have a group of around 100 on X. It has no name but has like-minded people. This (countering anti-Kannada narratives) is part of it,” said Krishna.

Over the last few months, pro-Kannada groups like Namma Naadu, Namma Alvike (NNNA), Banavasi Balaga, Bengaluru Kannadigas, and others have started mushrooming online. They push back against Hindi imposition, amplify conflict between local residents and migrants on the ground, pressurise the government to promote Kannada in every way possible and call out North Indians who refuse to learn the language. A similar anti-migrant sentiment has been rising in neighbouring Tamil Nadu and other non-Hindi speaking states in the country.

There are also efforts to reach out to non-Hindi-speaking groups from other parts of the country and turn this initiative into a pan-Indian movement. Plans to oppose Hindi Diwas have already been hammered out.

The movement is political, cultural and social.

“(Karnataka) Rakshana Vedike (KRV) will hold protests in Bengaluru’s Freedom Park. Another group called Banavasi Balaga will have a poster exhibition in Ravindra Kalakshetra on Hindi imposition. Our group (Namma Naadu Namma Alvike) will ask all Kannadigas to wear black clothes to banks, and hold a protest card stating we are against Hindi imposition. We will then post it online,” said Shivanand Gundanava, a 37-year-old entrepreneur and member of the NNNA said.

The original plan was to visit banks and other institutions that promote Hindi, but it hit a snag since 14 September falls on a second Saturday—a bank holiday.

The tension has ratcheted up over the last few days in the backdrop of two incidents that reveal the ever-widening cracks in this divided city. A Kannadiga autorickshaw driver, R Muthuraj, assaulting a young woman for cancelling the ride has been conflated into an issue about the attitude of local people. This was followed by a 6 September post on X by ManjuKBye reiterating that “Bengaluru belongs to Kannadigas. Period.”

The consensus among pro-Kannada groups is that the language has been sidelined under the tag of Bengaluru being “cosmopolitan”.

“Cities are cosmopolitan in different ways. In New York and London, the linguistic status of English is secure,” said Chandhan Gowda, a sociologist from the Institute of Social and Economic Change. “The cosmopolitan climate of Bengaluru, which depends on reciprocity between different language communities, is under strain.”

Also read: A new language war in Karnataka is brewing. This time over Tulu dignity

Guardians of Kannada

Behind the viral posts and memes are carefully thought-out campaigns. The ‘culture guardians’ operate in small circles, with one lead group doing the planning and strategising. The aim is to combat those accounts that show Kannadigas in poor light.

At 8.30 pm on Wednesday, at least 400 people logged into a Twitter space discussion on Hindi imposition that extended till midnight. The speakers included several prominent pro-Kannada voices including Purushottam Bilimale, the chairman of the Kannada Development Authority (KDA), KRV’s Arun Javgal, Kannada film director and lyricist, Kaviraj, popular YouTuber and historian Dharmendra Kumar among several others.

Each of them took turns to share their own experiences. Some were nuanced. But a few sounded the alarm likening Hindi imposition to “3rd stage cancer”, which if not stopped, would end up killing Kannada.

“The Hindi imposition is to project India as a homogenous group. It is political and meant to serve the interests of the Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party”

“We are not against Hindi but the State-sponsored imposition” was the disclaimer most speakers made. Many provided suggestions on how to raise more awareness. The online guardians are already on the job. Members called for a “Gokak-like agitation” to assert Kannada and oppose any effort to impose Hindi.

Around mid-June, a small yet vocal group of pro-Kannada speakers started a handle @Karnatakaparty1 for the group ‘Namma Naadu, Namma Alvike’ which translates to ‘our land, our rule’. It has a modest 2,159 followers but the handle and its members, supporters gain significant views and engagement, making it one of the more vocal and visible voices against Hindi imposition.

The trigger was the incident involving the Bengaluru auto driver who allegedly assaulted a young woman for double booking rides.

Within an hour of the incident, the video went viral across the county and even made it to national news bulletins. Shivananda Gundanavar blamed this on the powerful pro-Hindi lobby that “targets Bengaluru” and shows the city’s inhabitants in poor light.

“The Hindi imposition is to project India as a homogenous group. It is political and meant to serve the interests of the Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on the global stage,” he said.

Pro-Hindi handles have asserted that Hyderabad and Chennai do not have any compulsion on migrants to learn the local language and project Bengaluru as the only one with such an attitude.

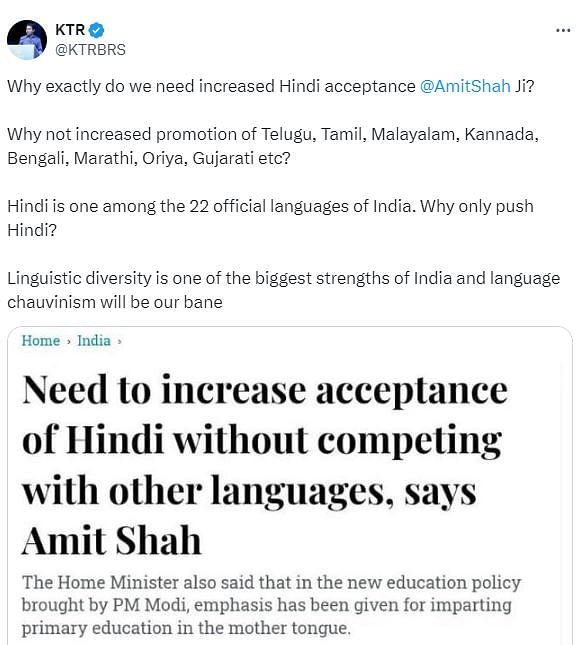

The statements by Union Home Minister Amit Shah that Hindi should be accepted as the language of work with consensus has drawn sharp reactions from non-Hindi speaking states.

K.T.Rama Rao, the former Telangana minister was quick to point out that there was no need for increased Hindi acceptance.

“Why not increased promotion of Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Bengali, Marathi, Oriya, Gujarati etc? Hindi is one among the 22 official languages in of India. Why only push Hindi?….” KTR questioned.

Any incident in India’s IT capital becomes instant news and often comes under the radar of the BJP’s media cell.

“It has become common to first provoke Kannada speakers and start recording reactions, which are then posted online. The organised pro-Hindi groups then circulate this and it projects Kannadigas as intolerant,” Gundanavar alleged.

Groups like Namma Naadu Namma Alvike, Banavasi Balaga, and Bengaluru Kannadigas don’t see themselves as rabble-rousers who vandalise signboards, and who take a more aggressive approach to make their point. Online groups, members argue. They voice more reasonable solutions.

“Many Kannadigas in the city—which includes the effortlessly bilingual older generation of Telugu, Tamil, Marathi, Malayalam speaking settlers, among others—feel that the more recent settlers from outside Karnataka don’t make an effort to learn Kannada and even disrespect it,” said Chandhan Gowda.

‘Don’t want to learn Kannada’

It’s been nearly two years since 22-year-old Sanchita B moved to Bengaluru to pursue her master’s in journalism but she barely speaks any Kannada except the word ‘gothilla’—which literally means ‘don’t know’. However, local residents see this as more of a sign of ignorance.

“I did not want to learn the language or culture,” she said.

Sitting in a small eatery just off the busy Hosur Road in Koramangala, Sanchita and her classmate Aryan list a variety of reasons for not attempting to learn Kannada.

“There is a sort of reverse racism here. I have experienced auto drivers cancelling rides when they see me,” she said, before quickly clarifying, “There have been good people [Kannadigas] I have met but the overall experience has been negative… I can sense the hostility.” she said.

She mirrored the arguments made by other migrants who resist learning Kannada. Those who’ve grown up on a diet of Hindi and Punjabi among other languages in North India find Kannada a difficult language to learn. Then there’s the inclusivity or lack of it. Many claim they face discrimination among social groups in their workplace and college campuses.

The online debate has even drawn people from outside Karnataka, like Dr Shivam, an oncology surgeon from Ahmedabad.

“This perception of assertion (imposition) is being generated,” said Shivam of the growing online clamour against Hindi imposition.

Sanchita can speak Kashmiri, Hindi, and English. Over the years, she has also picked up some Gujarati and Marathi from Pune where she spent a couple of years studying. She is even learning German online. Her classmate, Aryan, who is from Delhi, said he “tried learning” Kannada but “assumed that people would not make space” for him even then. In his college, the basis of social groups is largely language.

Incidentally, the waiter at the eatery, Prabhat Kumar Prabhakar, is from Bihar. After five years in Bengaluru, he can speak fairly fluent Kannada. Prabhakar’s boss, a Rajasthani, can speak 10 languages, including Kannada.

Krishna, Mallikarjun, Sanchita, Aryan, Shivam and Prabhakar are people who come

from different backgrounds and have little in common with each other. But their

respective stand on the issue of learning Kannada, or if Hindi should be the common tongue, makes them part of an increasingly inextricable part of each other’s lives.

“Migration without assimilation is invasion,” Mallikarjuna said, repeating the words of American entrepreneur and lawmaker, Bobby Jindal.

He is among the hundreds of people online who closely monitor any posts against

Kannada, Bengaluru, Karnataka, or the “glorification” of migrants as instrumental in giving India’s IT capital its identity.

Also read: Hindi hegemony will only end when other Indian languages like Tamil are reinvented

The auto driver incident

A big focus of the recent online pro-Kannada campaign has been what they call the mischaracterising of Bengaluru, following the auto-rickshaw incident.

“What the auto driver did was wrong but he was provoked. No one is talking about it. Though it had nothing to do with Hindi or Kannada, they (so-called outsiders) set the narrative that this sort of behaviour was common in Bengaluru and among Kannadigas,” Gundanavar said.

Demand for excess fares or aggressive posturing by auto drivers is ubiquitous in Bengaluru. But it is often conflated as the attitude of most local residents in Bengaluru toward migrants and projected as forcing the latter to learn Kannada or be discriminated against.

The auto driver was arrested, sent to jail for four days, and fined Rs 30,000. His licence is likely to be cancelled. The outpouring of support for Muthuraj, including an Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) leader asking people to donate for his legal fee, has further fueled the divide. Online, people were quick to comment on this latest episode.

“Let us all help the driver who slapped the woman passenger because he speaks my language….” said one X user, Siddarth who operates the @DearthofSid handle.

Technology divide

On Friday, X user @ManjuKBye said that anyone coming to Bengaluru who cannot speak Kannada “will be treated as outsiders”.

In response, @Slumdog08_ posted a meme in which three prehistoric men are pictured

hunting with bows and arrows in the mountains with the caption: “Bengaluru, if there were no outsiders”.

Memes or posts on this topic have often been offensive with some being outrightly racist. These provocative posts, sometimes by fake accounts, see significant online engagement, attracting vile comments and even threats.

On the ground, the aggressive pro-Kannada groups go unchallenged—some of them use intimidation, violence and vandalism as their main strategy. Even law enforcement authorities are sometimes seen to go soft on such elements.

In mid-February, pro-Kannada activists were seen vandalising and removing signboards with Hindi or larger fonts of English. It was after the Siddaramaiah government ordered that all commercial establishments should have at least 60 per cent signage in Kannada. The deadline to implement this rule was 29 February. But no cases were filed.

A section of the local residents insist that the people of Karnataka are more welcoming and accommodating and not aggressive like other south Indian states like Tamil Nadu. As a result, they are being taken advantage of. And by extension, learning Kannada is not seen as a requirement but a choice unlike say in Tamil Nadu where the resistance to Hindi is far more pronounced.

“Migrant parents have gone to court against the mandatory learning of Kannada in schools. They often say that Kannada is alien to them but will facilitate teaching of French, German for their children…write TOEFL, IELTS but will not learn Kannada. They want to retain speaking Hindi. We are not against Hindi but its imposition,” Mallikarjun said.

Bengaluru’s status as the technology capital of the country has also magnified the divide. In October 2022, the food and civil supplies department shot off a letter to food aggregator, Swiggy, for not teaching its delivery personnel Kannada, causing inconvenience to customers.

ATMs or the advent of mobile-based online payments have negated the need for interactions with banks in big cities. But bank employees refusing to speak Kannada with farmers in rural Karnataka have triggered and fueled several such clashes.

Chandhan Gowda blamed the advent of technology that has allowed people to come from anywhere and create their own “insulated” spaces that do not require interaction with the local residents. There was a time—barely a few decades ago—when the business community from outside Karnataka had to learn the language. Old Marwari and Gujaratis adapted to the local ecosystem. This is no longer the case now.

Most businesses and business-related interactions can be done online now, the need for learning the language as a profitable exercise sees a decline, he said.

Apps allow the booking of autos or cabs without conversation. There is online access to TV shows and newspapers from their respective regions, all groceries can be booked through the phone that deprives even the most basic of interactions.

“You can live in Bengaluru without the obligation of learning Kannada,” Gowda said.

Language politics

In July this year, the Siddaramaiah-led state government mooted a bill, which mandated employers to appoint 50 per cent of local candidates in management roles and 75 per cent in non-management positions. Barely two days later, it was rolled back, allegedly because of opposition from within the Congress party itself. In the IT sector, the industry body NASSCOM called the bill “deeply disturbing” while others like Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, TV Mohandas Pai called for it to be rolled back immediately.

“If this continues, Kannada may not survive,”

According to Gowda, the IT industry captains were quick to dismiss the state government’s proposal to reserve jobs for local people without taking the time to understand why such a move was even being mooted.

The issue of Kannada–part of the emotive and non-negotiable platform of ‘Nela, Jala, Bashe’ (land, water, and language)—strikes a deep chord among the people of Karnataka. But it does not carry significant political capital. Kannada Chaluvali Vatal Paksha’s Vatal Nagaraj and perhaps former Kannada Sahitya Parishat president G. Narayankumar were the only two leaders to have won a state election on the platform of language.

While political parties seldom contradict demands on the importance of Kannada, rarely is language the main poll plank. Support of groups like KRV is limited to lending support to the “injustices” meted out to southern states like Karnataka.

That said, Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah led the protests against the Hindi imposition by the Modi government who proposed a ‘three-language formula’ on Metro sign boards in 2017. He has been vocal about the declining share of ‘high performing states’ like Karnataka in the devolution pool and even invited CMs of non-BJP ruled states for a conclave to discuss this further.

“States with higher GSDP per capita, like Karnataka and others, are being penalised for their economic performance, receiving disproportionately lower tax allocations. This unjust approach undermines the spirit of cooperative federalism and threatens the financial autonomy of progressive states,” Siddaramaiah said Wednesday.

Even the decision to bifurcate Bengaluru’s city corporation into five parts has come under scrutiny as there are fears that migrant-heavy localities would make Kannada speakers a minority in their own city.

According to central government data, in the 40 years between 1971 and 2011 (last census), the growth of Hindi speakers is up 66 per cent. While the percentage of growth for Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Punjabi, Odia, Gujarati and others is an average of 11 per cent. Tulu has seen 7 per cent growth. Kannada speaker growth is at 3.73 per cent.

“If this continues, Kannada may not survive,” said Purushottam Bilimale.

The fear is real. So is the battle.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

My Karnataka is going to dogs. Sad developments. We want to become another Tamilnadu. Fighting over language all the time. Assholes.

Kannada is best hindi is worst

Hindi imposition cannot be accepted. It can be effectively fought against only if there is a South-Orissa-Bengal-Northeast alliance aginst it.

There are many placards behind english one. But, show me one in kannada. How irresponsible work it is. This shows, carelessness. Better to rectify.

We need to promote all regional languages, including South Indian, without imposing Hindi.

And we should also promote English as a link language across the country because there are only benefits to it. We need to ensure we can work together in a multi lingual and multi cultural setting, not by learning 1000 regional languages, but through English as a link language.

The picture shows Telugu. Who is responsible for this joke ?

Aww Dheeraj, that picture is in Telugu. You really worked into it with your eyes closed, didn’t you?