New Delhi/Gurugram: The wall of a tiny cafe in Delhi’s Lajpat Nagar is studded with postcard-sized posters of K-dramas. All major hits find a mention – Our Beloved Summer, Alchemy of Souls, Descendants of the Sun, and Vincenzo, among others. Everything else inside the cafe – named Seoul Station – is minimal and bright yellow, including a cute rubber duck collection. The aesthetics are completed by four tiny succulent pots, each holding a mini-South Korean flag.

India is the shining, unconquered territory when it comes to Korean food, and Koreans are wasting no time in starting their small and medium business ventures here. But the K-culture tsunami isn’t the only factor driving their interest and aggressive push. Korea’s food and beverage sector is already packed with too many players. Business persons also see Southeast Asia as a saturated market.

This prompted Seoul Station owner Oh Jin Woo to join Korean entrepreneurs who have opened eateries in Delhi-NCR. The 30-year-old from Seoul opened his cafe this January, spurred by the ever-rising popularity of K-dramas and K-pop in India.

A lethal combination of pop culture, cuisine and market dynamics has created fertile ground for a unique food culture to flourish. Indians are now spoiled for Korean food choices. Today, there are nearly 30 Korean-owned restaurants and cafes in Delhi and NCR, including multiple outlets by the same owner. Most are located in Gurugram and Noida where Korean expat communities live. Many new ventures have popped up in the last three years – an after-effect of shifting global markets and the Korean wave resurgence during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Lee Sang Hyun, owner of Korean street food chain Kori’s, has seen tectonic shifts in Indians’ interest in Korean cuisine. From starting with a small joint near Delhi University’s north campus in 2013 to having five outlets across Delhi, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh, Lee’s journey is a story of smart business acumen, perseverance, and the Midas touch of K-culture in India.

“When we educate ourselves about India, we learn that there is a section below the poverty line and also a sizable middle-class who can go out and eat,” Lee says about Korean entrepreneurs’ target audience.

For Kori’s, it’s the younger, content-devouring crowd, who enjoy their share of Korean entertainment. He knows that they are the people who are more comfortable eating out.

“In the next 10-20 years, the Indian economy will boom. We are at the stage which is the starting era of the peak of India’s economy,” says Lee.

After running a tight operation in north Delhi for four years, where he “wasn’t making profits”, Lee decided to move the location of his outlet. In the early 2010s, a Korean street food outlet selling fried chicken, chicken mayo, and mayo rice wasn’t drawing crowds from colleges or schools. His time in Delhi made him aware that Safdarjung in South Delhi had a huge concentration of students and employed people from northeastern states. The 38-year-old knew the Korean wave had already hit India’s Northeast by then.

“I was thinking of closing down before opening the Safdarjung outlet in 2016. I was going through a serious dilemma. But then, because of all the time and energy and effort that I have put into the business, I thought let’s give it one last try,” Lee says while conversing in fluent Hindi with his staff at Kori’s Safdarjung branch.

Lee’s switched up his menu. He shifted from Korean fast food to more authentic Korean cuisine – kimbap, tteokbokki, jajangmyeon. Kori’s has also introduced Dosirak, a Korean lunch box that includes a full meal, at their new outlet. The gamble of an upgraded menu and a new location paid off. Today, the Safdarjung branch operates in a three-story building with a seating capacity of 200 people.

Also read: Kalpana Soren’s life was family time, yoga, music. Now it’s rallies, speeches, interviews

A tempting ‘blue ocean’

Seoul Station’s founder Oh Jin Woo wishes he had opened his restaurant in Safdarjung or Saket or even the Tibetan settlement colony, Majnu Ka Tila. While social media gave him a clear picture of the demand for Korean cuisine in India, demographic complexities were something he had to learn practically. His elder brother, who often visits India for business purposes, had suggested Lajpat Nagar as a location for his eatery.

“If I could go back in time, I’d never open my cafe here,” Oh says. Despite the initial hiccups, he is upbeat and already planning to open another branch at a better location.

Oh says that Koreans look at India as a ‘Blue Ocean’ – a growing market that is uncontested or with few competitors. It’s a contrast to ‘Red Ocean’, which is an overdeveloped or saturated market, much like their home country of South Korea.

“A Red Ocean already has too many people doing a certain business. Blue Ocean is just starting to pick up,” explains Oh, who used to work at a trading company dealing in luxury brands in Osaka, Japan.

For Koreans, the entire Southeast Asia is a Red ocean. “There are so many Koreans living there and running cafes. But in India, there are not many. Only a few famous Korean restaurants,” he says.

An extensive traveller who has previously lived in Mexico and Australia, Oh was surprised to find that Korean-owned hair salons were missing in Delhi-NCR. “There’s only one, in Gurugram,” he gasps.

“It’s my opinion that Koreans feel comfortable starting something where other Koreans are already present. Sometimes that’s absurd because we create our own competition,” Lee says

For Korean entrepreneurs, choosing the right location for business is navigated by more than people’s eating habits. The steady flow of customers from the larger Asian expat community in Gurugram and Greater Noida has led to the mushrooming of Korean outlets in these pockets of NCR compared to Delhi. But it’s also a mix of cultural factors.

“It’s my opinion that Koreans feel comfortable starting something where other Koreans are already present. Sometimes that’s absurd because we create our own competition,” Lee says, noting it could be because of culture and language.

India might be a vast Blue Ocean but the playing field is limited. It’s early days of business, and Oh has understood the rules of the game. Introducing unknown food items is off the cards, for now.

In April, he participated at the Korean Street Fair in Saket’s DLF Avenue Mall, where he prepared four items – cheese corn dog, samgak (triangular) kimbap, and two kinds of bibimbap.

“But we could sell only corn dogs. So, I’m trying to expand the corn dog menu and add more options. Trying to popularise an unknown Korean food item is too difficult a task for an individual,” he says. The bestselling Korean dishes in India have been popularised by K-dramas and K-pop stars.

Oh runs the cafe from 11 am to 11 pm, every day of the week, with three staff members. His mannerisms exceed the quintessential traits of Korean food outlet ethics. He warmly greets his customers, sending them off with a jolly smile and a 90-degree bow. He is thankful for each one of them. They are the people keeping him going as he manages the kitchen, takes delivery orders, and deals with tedious paperwork and corrupt government officials.

“Everyone (government officials) comes and asks for money,” he says, recalling his struggle to get a license, certifications and permissions.

Victors and the vanquished

Oh is among the few young Koreans who turned to India to do business. It was partly because of his elder brother’s familiarity with the country.

Kori’s owner noted that the interest of Koreans in exploring India for small and medium businesses is still low and the survival rate of Korean restaurants is “not so high”.

“People who come and open restaurants in India don’t have much idea. They don’t set up business strategically. They come, they open restaurants and if it’s not successful, they close,” Lee says.

Most of his observations rang fearfully true for Seoul Station’s trajectory so far. Korean entrepreneurs open businesses in India with less profitable conditions that are made worse by language barriers and cultural differences.

“When people from Korea come and start their business in India, they have the Korean standard in mind. Usually, they end up paying more rent. They feel the rent is cheap compared to Korea, so they don’t bother. And Koreans don’t bargain much because we get irritated,” he says.

When Lee tried to hire Koreans to work in India, many were sceptical about moving here. Seventy to 80 per cent weren’t interested unless they were paid a hefty sum. Kori’s currently has nearly 200 employees, most of whom are Indians.

“Koreans still don’t see India like they saw China in the early 2000s. But they will sooner or later,” he adds.

“It’s (a job opportunity in India) not attractive in comparison to the United States, Canada, Australia, or even Southeast Asia,” he says.

Lee says he sees more Koreans living in India now. But he attributes it to a shift in global markets.

“More and more people are coming in not because of the Korean wave but because China’s dominance is going down.”

Koreans did and still do a lot of business in China, he says, but “definitely less” in comparison to “the peak time” of 2000-2019.

“Koreans still don’t see India like they saw China in the early 2000s. But they will sooner or later,” he adds.

Korean Youth Commerce Association in India (KYC) president Kim Jin Bum underlined that the number of Koreans entering India’s F&B sector has shot up in the last three years. And while new players are steadily trickling in, the old ones are exerting their first movers’ advantage and delving deeper into the Indian market.

Kim and his mother started one of the oldest Korean restaurant chains in Delhi-NCR—Gung The Palace—in the late 2000s. They opened their first branch in Green Park before expanding to Gurugram and then to Noida.

Gung’s Gurugram outlet in Sector 29 is a dot in the chaotic ocean of restaurants, bars, and spas that floods the area. But it’s a stone’s throw away from the headquarters of Hyundai Motor India. On the inside, the restaurant has an elegant traditional Korean setting—visitors remove their shoes before stepping inside private dining areas.

The prices are a far cry from the budget-friendly offerings of Kori’s and Seoul Station. Kim has zeroed in on a customer base—Korean expats and Indians mostly over 30s who can afford premium Korean dining.

“I opened Gung with my mother in 2007. There were hardly any Korean restaurants then except a few illegal ones in the Safdarjung area. I decided to open my business knowing that India would grow, so why don’t we do authentic Korean food,” says Kim, who mostly spends his days at the Gurugram branch. Kim’s tryst with India happened because his father was a diplomat.

After being in business for nearly 17 years, Gung opened its first franchise in Pune in March, which is owned by an Indian. The next one will be opened in Arunachal Pradesh’s capital, Itanagar, later this year.

“The owner of the franchise will be Indian. This means there is a demand for Korean food. Previously, our customers (in Gung’s first branch in Delhi) were Korean, Japanese and Chinese. But since the pandemic, 80 per cent are Indians,” says Kim, who studied Economics at Delhi University’s Ramjas College.

Kori’s has seen a similar shift in its customers’ demography. In the early days, Lee says his “mainland” clientele was under 20 per cent but now the ratio has flipped. However, Lee is still more focused on expanding in the northeast. By this year’s end, Kori’s will make its debut in Shillong and also open a second outlet in Itanagar. Lee has plans to convert his brand’s cloud kitchen in Gurugram to a brick-and-mortar establishment.

Also read: Art meets Ayodhya. NGMA, Lalit Kala Akademi are remaking India’s culture scene

Childhood dreams made affordable

It’s not only Korean men who are making inroads into the Indian F&B sector; women are exploring the lucrative market at an equal pace. Park Hae Young was a fresh graduate in the spring of 2021. The pandemic was still at its peak and the borders of most countries were tightly locked. Park was determined to work abroad and India was one of the few nations that still allowed foreigners to come and work.

The same year, Park joined the Korea Trade Promotion Corporation (KOTRA) office in Gurugram.

“I wouldn’t have come to India otherwise,” Park says.

“Saving up money to open a cafe in Korea would have been more expensive. But with my finances, I knew I could start one in India,” Park says.

Her job at the Korean government-funded organisation paved the way for her entrepreneurial journey. She first studied the Indian market and then learned about the kind of support small and medium Korean businesses needed in India.

“Saving up money to open a cafe in Korea would have been more expensive. But with my finances, I knew I could start one in India,” Park says.

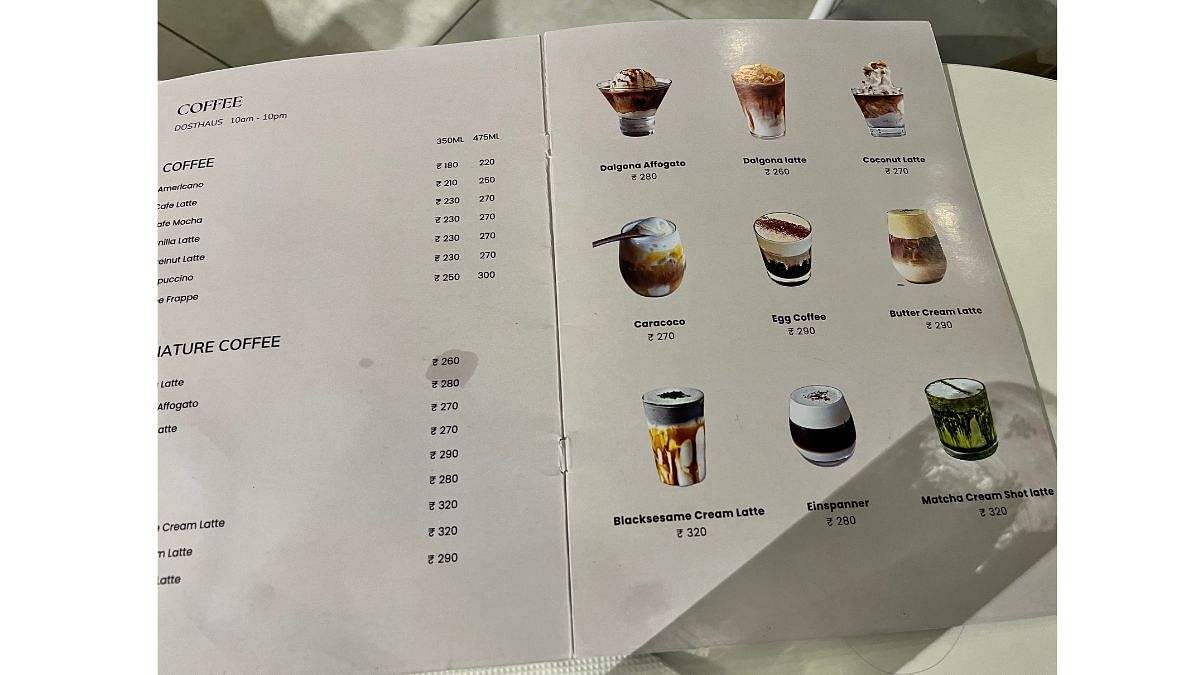

She worked at KOTRA for a little over a year and by December 2022, opened a quiet cafe – Dost Haus – in Gururgam’s Sector 43. Far away from the cluster of Korean eating joints on Golf Course Road, Park’s target wasn’t Koreans.

She was confused by the absence of small cafes in Delhi and NCR. “There are cafes every five minutes in Korea. But in India, I only saw cafes and coffee shops of big companies,” Park says, who is also good friends with the owner of Seoul Station Cafe.

The 28-year-old had her goal set – to start a quaint, white, minimalistic cafe where one could sit and work or bring dates. For one year, Park didn’t take a single day off. She would be the first to open the cafe at 10 am and the last to leave at 10 pm.

“I used to work 12-14 hours a day. But I realised it’s important to find time for myself. I shifted to a place closer to the cafe. That gives me some time,” says Park, who personally sources items for the cafe’s inventory and designs the menu.

She’s still coming to terms with the hefty taxes foreigners need to pay in India to run their businesses. The other challenge is understanding the Indian customers’ expectations. Unlike in Korea, where most cafes specialise in one item, customers in India demand variety. That’s why Park couldn’t go along with her initial plan to focus only on Korean toasts.

She added different kinds of cream coffees, kimbap, waffles and bingsu to her menu. Despite the challenges, cafe life has allowed her to realise her childhood dream at a much cheaper price.

“I had a dream of having a cafe in front of the beach. My mother ran a cafe like that in Korea. Even though there’s no beach here, I thought I could still start a cafe,” Park says with a smile.

Sitting on the first floor of a mall, Park lives her dream while overlooking dusty treetops and a skyline of residential buildings.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)