Lucknow/Noida: An imposing sandstone building with peacock installations stands out in Lucknow’s Gomti Nagar. With its sprawling grounds, pristine park, and sweeping staircase, it defies the typical image of a sarkari building. Yet, Bhagidari Bhawan is exactly that. It’s a free residential coaching institute for students from the SC-ST-OBC communities seeking to fulfil their UPSC dreams of becoming civil servants.

Complete with cavernous lecture halls and a well-stocked library, Bhagidari Bhawan is abuzz with aspiration and a sense of possibility. It reflects Mayawati’s rallying cry in the early 1990s as she burst into political headlines: “Nahin chahiye CM-PM, hamein chahiye SP-DM”—a slogan that resonated with the power that the civil services hold for the Dalit community. The government-run coaching centre currently accommodates close to 200 aspirants honing their skills for the UPSC and provincial civil services (PCS) exams. Officials claim that over 500 alumni now serve as officers in the PCS.

“I have cracked the PCS exam. I would never have been able to rise up the ladder without the availability of this scheme,” said Chote Laal, a 29-year-old from a poor Dalit family in UP’s Jaunpur. “The fortunes of my family have changed.” But Laal is not done yet. He remains at Bhagidari Bhawan, determined to clear the UPSC exam, the ultimate goal for many young people from marginalised communities chasing respect, power, and social mobility. He’s also mentoring his juniors who are trying to crack the state exam.

Bhagidari Bhawan is one of the flagship projects of the Bahujan Samaj Party government, the first dispensation in Uttar Pradesh to serve a full term, from 2007 to 2012. Helming it was Mayawati, once described by Time magazine as “Queen of the Dalits”. As Chief Minister, she launched a flurry of projects aimed at elevating the SC-ST-OBC communities, with an eye to the past, present, and future. She built huge memorials to Dalit leaders to mend historical wounds, allocated housing to uplift the urban poor, and started nine institutes, including Bhagidari Bhawan, for aspirational young people to get higher education and coaching.

But Mayawati’s legacy eventually turned into a battleground, marred by charges of financial impropriety, “megalomania”, and fiscal mismanagement. After her government lost power, her successors dismantled or rebranded many schemes and projects, and her name became more tied to controversies than her convictions.

ThePrint travelled across Lucknow and Noida to investigate the fate of BSP initiatives for uplifting Dalit lives, and how subsequent administrations have taken them forward— or not.

Political opponents and voters alike wonder where the ‘iron lady’ Mayawati has gone—her silence on a number of issues is deafening.

Also Read: Villagers use Saraswati riverbed for cow dung, cremation, crop. ‘Where do we keep cattle?’

Mayawati’s embattled legacy

About 400 kilometres from Lucknow, the Ambedkar Hostel in Noida is slowly succumbing to neglect. Established by the BSP for underprivileged students, the hostel’s lawns have been taken over by bushes, shrubs, and weeds—a haven more for snakes than the residents. Inside, broken toilets and low quality, barely edible food greet students daily.

This hostel’s decline could well serve as a metaphor for Mayawati’s fading legacy in Uttar Pradesh. Not every ambitious policy or new construction has survived the test of time or successive governments. After its meteoric rise in the 1990s and peak in 2012, the party’s vote share and public presence have eroded steadily over the past decade. Political opponents and voters alike wonder where the ‘iron lady’ Mayawati has gone—her silence on a number of issues is deafening.

Still, Dalit students at the Ambedkar hostel sing her praises. They recall her era as a time when many of their friends and family members thrived and gained access to better education.

“For a short window of five years it seemed like the world belonged to us as much as it does to the rich. Not anymore,” a student said on the condition of anonymity.

Nearly three decades after Mayawati became the first Dalit CM of Uttar Pradesh, her political influence is thinning and the shelf life of her status quo-defying policies and institutions is questionable.

But during her four tenures as CM— in 1995, 1997, 2002-2003, and 2007-2012— she set about disrupting the political narrative and launching numerous measures to upend the existing caste hierarchy. A BSP booklet from 2022 details numerous such initiatives. Education takes up many inches, including six universities, seven medical colleges, six engineering colleges, over 200 degree colleges, and 500 high schools across Uttar Pradesh. Social infrastructure was another big area of focus, with more than 28,000 Ambedkar villages and 2,400 community halls for Dalits being set up. The icing on the cake: sanctioning and starting construction on the grand 165-km Yamuna Expressway.

“We built New Lucknow,” remarked Raju Gautam, the Prayagraj coordinator for the BSP. To some extent, it’s a claim that even critics concur with.

There was so much criticism about the costs incurred on (Mayawati’s) projects, but today nobody questions the expenditure on temples.

-Ravi Kant, Lucknow University professor

Whether through sandstone or symbols, Mayawati brought Dalit iconography on the streets, infusing a sense of pride among the oppressed castes of Uttar Pradesh. She built brick-and-mortar edifices—to Ambedkar, to her mentor Kanshi Ram, to herself— that nobody could ignore. Colleges, colonies, and even districts were renamed after Dalit icons. Amethi became Chattrapati Sahuji Maharaj Nagar, Sambhal became Bheem Nagar, Hathras became Mahamaya Nagar, to name a few.

Some of this legacy was stamped out after the BSP lost power in 2012. Mayawati’s successor, Akhilesh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party, went on a spree to restore the old names of six districts renamed by Mayawati. He also renamed many schemes and projects launched under the BSP government. As many as 30 schemes were scrapped, including BSP’s decision to reserve 23 per cent government contracts under Rs 25 lakh for members of the SC and ST communities. Akilesh even changed the traffic police’s uniform colour, moving away from Mayawati’s preferred blue.

Today, the BSP, SP, and BJP all claim credit for big-ticket projects like the Yamuna Expressway, but what became of initiatives that once bore Mayawati’s definitive stamp?

Mayawati’s message, cast in sandstone across statues and gargantuan parks, still has takers, regardless of how her party does in the hustings.

Housing and hostels

Ahead of the 2022 UP assembly elections, Mayawati took a dig at CM Yogi Adityanath, accusing him of living in a “bungalow” while her government “gave houses to the poor” under the Manyavar Shri Kanshi Ram Shahri Garib Awas Yojana, launched in 2008.

She boasted of delivering 1.5 lakh houses to beneficiaries, but the UP housing board’s website paints a somewhat different picture. Their records show the scheme aimed to build over 70,000 houses for the urban poor across 49 districts, with 42,000 completed in two phases.

Lucknow’s Para area has 2,200 such houses. These are tiny one-bedroom residences, covering only 350 sq ft, but they were a major step up for many residents. Some moved here after a lifetime of living in rented rooms in slums or in shanties along the railway tracks.

Former construction worker Janaab Khan has been living in one of these apartments since 2013. Now retired, he says he wouldn’t have been able to keep a roof over his head without the help of the Shahri Awas scheme. “Behenji made me a landlord. I wouldn’t have imagined this in my wildest dreams,” Khan said matter-of-factly. “When I first moved here, I wasn’t even able to make rent.”

But even Khan can’t overlook the dilapidated condition of the society. Green fungi have eaten away at the concrete awnings, causing them to crumble. The walls are so fragile that residents find it difficult to nail photographs to them. The floors already look like Mumbai’s potholed roads, although the building is only a little more than 10 years old.

Our great leaders used to say– ‘go write on the walls that we are the rulers of this nation’—but the Dalits didn’t even have walls to call their own.

-Raju Gautam, BSP leader

“This isn’t Behenji’s fault,” Khan said. “This is Phase-II of the project, which was finished after the BSP government was voted out of power, so the quality of the work is not top class. Phase-I, which was completed while she was still Chief Minister, is still in good condition.”

By the looks of it, Khan is not entirely wrong. The exterior of Phase-I houses of the project did look in a better condition.

But both the colonies are afflicted by administrative apathy. The community market has no shops because local gangsters have captured them, residents say. The community marriage hall, located on the first floor of the market, has suffered the same fate and remains locked. Though the halls were supposed to be free to use, residents allege local dons have to be paid off for access.

Instead of a busy marketplace, this area has become a den for drug addicts, with broken Tuborg bottles and smoked beedis littering the ground. Sanitation is an issue in the colonies too. Residents complain there’s no proper garbage disposal, and municipal waste collectors visit just twice a week instead of daily, as was promised.

Worse though the colonies may be for wear, BSP’s Gautam hails the scheme as one of the party’s most “revolutionary” initiatives. “Our great leaders used to say– ‘go write on the walls that we are the rulers of this nation’—but the Dalits didn’t even have walls to call their own. Behenji gave us the four walls to call home,” he said.

Another “dream project” of the Mayawati government was establishing Ambedkar Hostels in every district in Uttar Pradesh. The idea was for SC/ST students to be able to access quality education with ease.

One of these was the Greater Noida men’s hostel, which once boasted a horticulture garden, a fountain, a cricket ground, and a basketball court. But all of it has become a jungle now. Officials at the hostel said the horticulture contract of the hostel has not been renewed since 2017, allowing wild shrubs to reclaim the grounds. A small gym was also built in the hostel, but there are no government funds for the upkeep of the machines.

“In 2011, the hostel was at its full capacity of 500 students but now hardly 200 boys are living here,” said the hostel warden, asking not to be named. “This is because under the Mayawati government, students could enroll for courses with zero fee, and apply for scholarships (through the social welfare department). Now that facility has been revoked, so students are unable to afford education outside (their village and towns).”

The students who do reside here now claim the living conditions are dismal and they have to get even broken bulbs and fans changed at their own expense. “We are not even getting quality food to eat,” an angry 25-year-old resident said. “Can’t the government even give us decent anaaj?”

Ghar Ghar Ambedkar

While the Kanshi Ram Awas scheme set its sights on helping the urban poor with housing, the Ambedkar Gram Vikas Yojana spruced up living conditions in rural UP.

Kicked off in 1995, during Mayawati’s first term, the scheme focused on providing roads, electricity, and clean drinking water to villages where over 40 per cent of residents were from Scheduled Castes.

One such village was Puraina in Lucknow district, where the scheme was introduced in the early 2000s. But the residents don’t remember a lot changing upon their declaration as an Ambedkar Gram. “Mayawati only gave us a road and a drain. We didn’t get anything else. Look at my house, I actually need a colony (house),” resident Kaushalya, a labourer in her 40s, said.

Other than better infrastructure, the scheme also provided for Ambedkar statues in villages, but implementing this too has occasionally been a challenge. In Puraina, villagers claim there was pushback from their upper caste neighbours.

“It was decided that a statue of Babasaheb would come up on vacant land,” said resident Mohan Lal Gautam, pointing to a gram panchayat property. “But the general castes of the village did not let it happen, and the murti was installed 5 kilometres away from here. Why didn’t anyone from the government help us install a statue near our houses so we could have paid Babasaheb respects on a daily basis?”

But it’s not just a tale of disappointment. Om Prakash Yadav, a teacher from Mau district who was visiting Lucknow, said the scheme had benefited his village, including members of the OBC community he belongs to. “It’s only after the village became an Ambedkar Gram that everyone in my community got access to drinking water and electricity,” he said.

The Ambedkar village scheme was later renamed as the Lohia Samagra Gram Vikas Yojana by the Samajwadi Party government, after their own icon Ram Manohar Lohia. In the 2009 general elections, the Congress threw its hat in the ring by launching a similar scheme, Pradhan Mantri Adarsh Gram Yojana, to woo Dalits. But along with the party’s fortunes in UP, the scheme eventually faded into obscurity. The BSP promised to revive the scheme if it came into power in the 2022 elections, attesting to its popularity even if this didn’t translate to votes.

Educational institutions

The flashiest jewel in Mayawati’s sizable crown of educational institutes is the Gautam Buddha University in Greater Noida. Sprawled over 511 acres, the campus is remarkable for its size as well as its fortress-like aesthetics. And there’s no mistaking who reigns supreme. GBU doesn’t have a moat per se, but there’s a sarovar (lake). In the middle is a statue of Gautam Buddha, flanked by Mayawati and BSP founder Kanshi Ram standing next to him like generals. In no other university is the BSP iconography quite this loud.

On the academic front, there are 6,000 students in the university, with Dalits getting a 50 per cent rebate. The rest of the fee is taken care of by the social welfare department of Uttar Pradesh, a GBU official said.

The university boasts a well-known programme in Buddhist Studies, drawing students from all over Asia. Right now, the hush of exams has descended upon the campus and few students are in sight.

“This place makes me feel close to Buddha because it is so quiet,” said Nguyen Thi My Chi, a 49-year-old monk from Vietnam who has been studying at the university for the past decade. Like her, other monks from across Asia can be spotted strolling the expansive walkways or resting among the trees.

Another innovative institution launched by Mayawati is the Dr Shakuntala Misra National Rehabilitation University, which caters to disabled students and is equipped with state-of-the-art infrastructure to address their needs, from comprehensive wheelchair accessibility to customised sports facilities such as wooden badminton courts. For once, it’s not named after a Dalit icon but after the mother of BSP leader and former Rajya Sabha member Satish Misra.

For visually impaired students, it offers a well-regarded Braille press and library. Deaf students benefit from interpreters stationed in most classes, an institute dedicated to Indian Sign Language and deaf studies, and readily available support.

The university treatment facilities, including its Artificial Limb and Rehabilitation Centre, offer services completely free of cost to students as well as the general public.

DMSRU has 4,700 students enrolled in a range of programmes in law, management, engineering, arts, and commerce. Half of all seats are reserved for disabled students, with 50 per cent of those designated for the blind.

“We have 50 computers with Keno software, which allows students to translate text to audio easily,” registrar Rohit Singh said. The college also regularly conducts sensitisation workshops to bring abled and disabled students together and foster a supportive environment. The biggest challenge they face is finding interpreters– there were 15 openings last year, but only 12 applications were received.

This is one university which has grown from strength to strength, with a prosthetics lab launched by Yogi Adityanath recently.

However, political winds have not been kind to other innovative projects. A case in point is the Manyavar Kanshi Ram Arbi-Urdu-Farsi University, established in 2009 to promote the study of Arabic, Persian, and Urdu, among other subjects.

After the BSP’s exit, its name became the subject of contention. In 2012, the Samajwadi Party, reportedly in a bid to please a section of Muslims, scrubbed Kanshi Ram’s name off the institution, unveiling it anew as Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Urdu-Arabi-Farsi University. Then in 2020, the Yogi government took another swing at the nameplate, axing “Arbi-Urdu-Farsi” and replacing it with the more generic word “bhasha” (language).

Today, it’s called the Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti Bhasha University, and not everyone is happy about it.

“Our university has always struggled with an identity crisis,” said an official from the college on the condition of anonymity. “First, Dalit students felt welcome here. Then, with the name change (under SP) Muslim students wanting to study Arabic and Urdu felt encouraged. And now with the name change to ‘bhasha’, students are further confused as to what we teach! This is not a language-course-oriented university to begin with.”

Mayawati has redefined public space for Dalits in Lucknow, transforming the city of nawabs into a city of parks.

Silent Mayawati

Over the last few years, Mayawati seems to have largely receded into the background of state and national politics, avoiding direct clashes with the BJP. She’s silent even when allegations such as being the “B-team” of the BJP are levelled at her.

The word on the street is that she fears ED-CBI action which could lead to arrests of her family members. Others speculate she doesn’t want to pick sides before the elections. “Her silence seems strategic”, said Lucknow University professor and political analyst Ravi Kant.

But if stones could speak, they would tell the story of everything Mayawati ever stood for, good or bad, at the height of her powers.

Her message, cast in sandstone across statues and gargantuan parks, still has takers, regardless of how her party does in the hustings.

The parks have emotional value. But that’s where the value of these memorials and parks ends

-SR Darapuri, president of All India People’s Front

Mayawati has redefined public space for Dalits in Lucknow, transforming the city of nawabs into a city of parks. These include the 10-acre Ambedkar Memorial, the 112-acre Manyawar Shri Kanshi Ram Ji Eco Park and, bordering it, the 32-acre Manyawar Shri Kanshi Ram Smarak Sthal. Next to the Ambedkar Memorial is the “marine drive”– a concrete walking path along the Gomti River featuring a colossal marble statue of Gautam Buddha.

In Noida, another major park project is the Rashtriya Dalit Prerna Sthal and Green Garden, situated near the film city along the Yamuna River. Sprawling across 82 acres, this park also features huge sandstone elephants and statues of various Dalit icons like Jyotiba Phule, Kabir, Ravidas, Periyar, and Ambedkar.

But for some it’s now all stone and style, but no substance.

Even Mayawati’s supporters express anger against their leader for abdicating her duty and leaving Dalits in the lurch.

“Mayawati has no presence anywhere. Not on the ground, not on social media… nowhere. It’s not like there are no crimes against Dalits committed these days… but she offers no support. But there is no word from her,” said Prakash Sonkar, an economics student at Shakuntala Misra University. “Where will Dalits get support from if not the BSP? The party has killed the Dalit movement.”

But Sonkar hasn’t given up entirely on Mayawati. “We still have full faith in her. We hope for a comeback,” he said.

Also Read: Unlike Colston or Columbus, Ambedkar Memorial statues deserve their place in public spaces

Solace in stone

The rise of the Bahujan Samaj Party under Kanshi Ram and Mayawati fulfilled the aspirations of many Dalits. With the rallying cry, “Baba tera mission adhoora, Kanshi Ram karega poora” (Kanshi Ram will realise Babasaheb’s dream), the party inspired hope. It appeared that BR Ambedkar’s lifelong quest to place power in the hands of the marginalised was finally bearing fruit.

When Mayawati became the CM, less than a decade after the BSP’s first election, and then repeated the feat three more times, there was even talk that she might one day become Prime Minister.

However, the reign of the “Dalit queen” was dogged by controversy and disillusionment took root. Images of her wearing massive money garlands, said to be worth crores, and allegations of corruption in park funding tarnished her image as a leader of the poor and downtrodden.

“Yes, the parks have emotional value. But that’s where the value of these memorials and parks ends,” said SR Darapuri, a former IPS officer and currently the president of the political party All India People’s Front. “The statues are abnormal. The public installs statues of leaders, not the other way around. I don’t know how much money was spent.”

Darapuri, who is from the Dalit community himself, worked closely with Kanshi Ram as the latter was rising in Uttar Pradesh politics. But to him, the BSP squandered the opportunity it was given, along with public funds. “UP Dalits are the worst off in northern India,” he said.

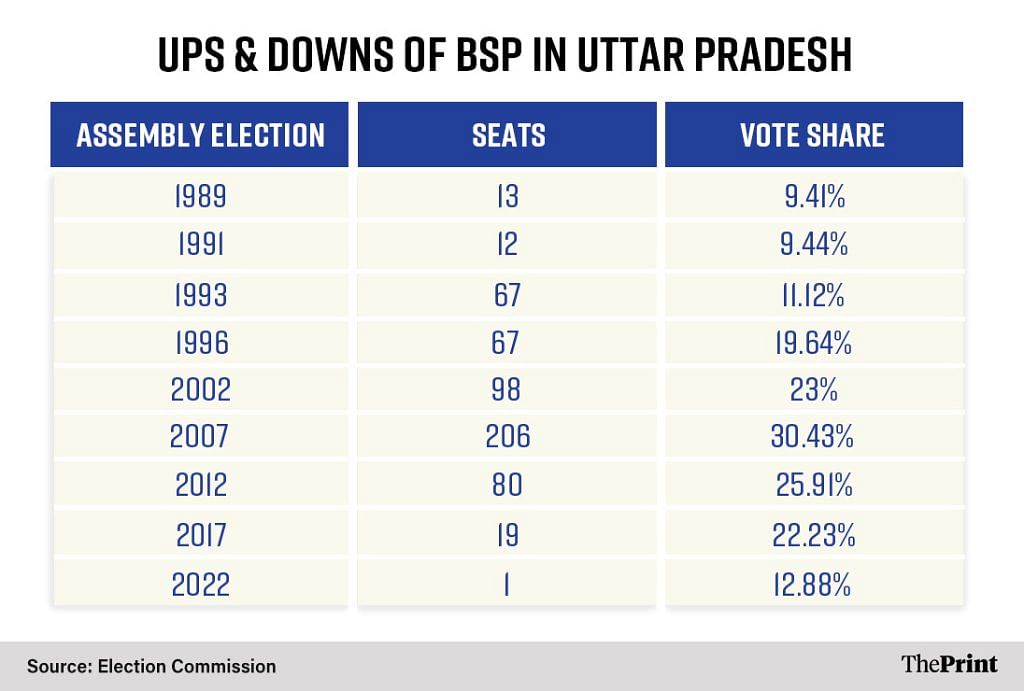

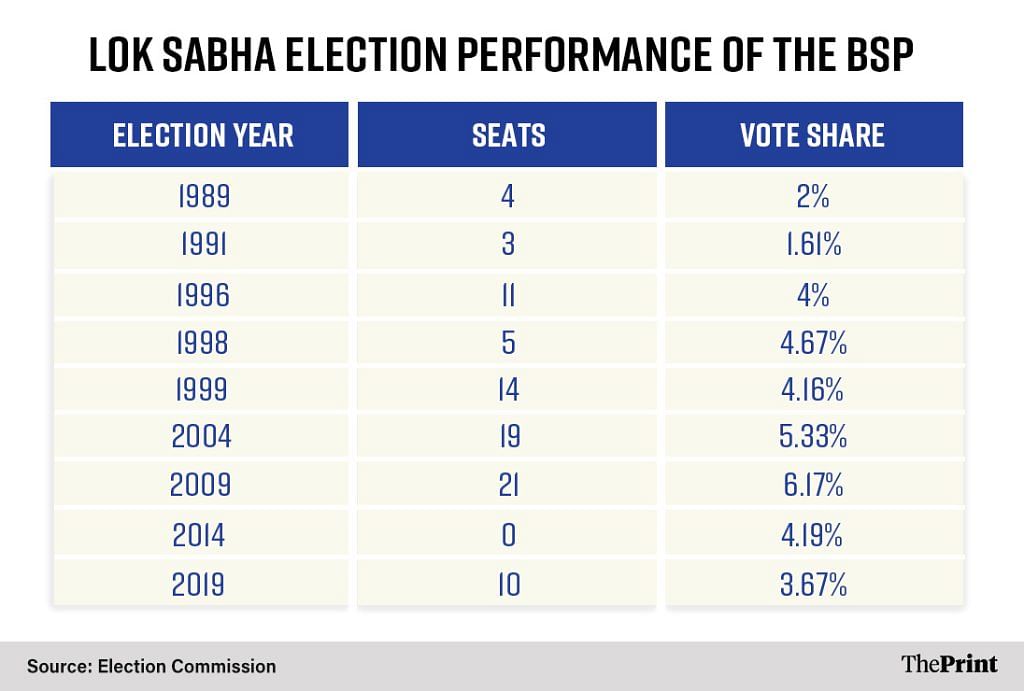

Even the BSP’s wave of welfare schemes for the marginalised castes could not recover its support base. From winning 206 seats in 2007, it was able to secure victory in only 1 in 2022.

But for Ravi Kant, Mayawati’s imprint on the state is not easily wiped out. “Mayawati installed statues of Ambedkar in thousands of villages in Uttar Pradesh, she built houses for the poor under the Kanshi Ram Awas Yojana. The various memorials help spread the messages of Dalit leaders to the masses,” he said. “There was so much criticism about the costs incurred on these projects, but today nobody questions the expenditure on temples.”

Regardless of their political affiliations, Dalit visitors, tourists, and residents still take pride in Mayawati’s monuments. Fortresses and palaces and temples across India have been built on the back of invisible Dalit labour, but here they are in command.

As the sun sets, people of all ages mill around the Ambedkar Memorial. It’s not just a homage to BR Ambedkar, but a monument to the BSP’s legacy. The hundreds of elephants—the BSP’s symbol— installed throughout the memorial, alongside statues of Kanshi Ram and Mayawati, serve as a constant reminder that a Dalit-led party successfully wielded political power in India’s most populous and electorally significant state.

Some come here to reflect on the past, others for inspiration.

Three elderly men sit on the on the grand staircase leading to a gallery of statues, the weight of history seeming to settle on their shoulders as they contemplate the progress made by their community and the long road that still stretches before them. “This memorial preserves our history, the history that was forgotten. It has been resurrected by Behen Kumari Mayawati,” Ram Chandra Tirpude, a retired engineer from Madhya Pradesh said, holding back tears.

In another corner, Mau teacher Om Prakash Yadav leads a group of Class 9 students, all from the ST community, on a tour of the premises, pointing out the statues of elephants. “Jai Bheem!” the students chant dutifully, more interested in scampering around.

“Books are not enough,” Yadav said, corralling the rambunctious children. “True inspiration will come from places like the Ambedkar Smarak.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)