New Delhi: When Dutch health company Koninklijke DSM and Swiss flavour maker Firmenich decided to merge in 2022, their biggest hurdle emerged from an office block in South Delhi–the Competition Commission of India. The commission couldn’t even scramble together the necessary quorum for a meeting to approve the global merger that was greenlighted in nine countries already. There was no chairperson at the commission for seven months to push things through.

The DSM-Firmenich merger was just one of the 20-odd deals worth $1.5 billion pending before the CCI last year. Lawyers had to approach the government to get the ball moving. A high-profile international merger being held up in India was embarrassing for a country that aspires to be a global leader.

The CCI, formed in October 2003, was meant to be a “game changer” for the Indian markets by keeping them competitive and protecting consumer interests. However, it has increasingly come under scrutiny from large Indian companies, startups that are at odds with big tech giants like Google, as well as former members of the commission who allege that its ambitious scope is being swept away by the ‘ease of doing business’ mantra.

“I think it will come through as a regulator that has not lived up to its original mandate and promise. To some extent, you could say that there may be regulatory capture also,” says former CCI chairperson Ashok Chawla.

The logjam over the Koninklijke DSM-Firmenich merger was the result of the CCI being left with only two members since October 2022, when Ashok Kumar Gupta, then-chairperson, demitted office. It needs a minimum of three members to operate. The approval for the deal from the CCI came only on 3 April, not because an appointment was finally made, but because Attorney General R Venkataramani and the corporate affairs ministry found a way out in a 13th-century tenet—the ‘Doctrine of Necessity’. It was laid down precisely for such exigencies, permitting actions that may otherwise be illegal to prevent greater harm in certain situations.

The CCI found a shortcut in the fine print to to invoke the ‘doctrine of necessity’ to circumvent the lack of quorum.

There is some kind of lethargy; complacency is setting in. Industry feels that those who are victims of anti-competitive conduct or abuse of dominance don’t get justice in time

— MM Sharma, head of competition law practice, Vaish Associates

By the time the new chairperson, Ravneet Kaur, was appointed in May last year, the damage had already been done. Industry experts had already written to the government, asserting that delays in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) approvals were having a debilitating impact on investor confidence in India, and international market observers had taken note.

“There is some kind of lethargy; complacency is setting in,” says MM Sharma, head of the competition law practice at Vaish Associates. He adds, “Industry feels that those who are victims of anti-competitive conduct or abuse of dominance don’t get justice in time.”

Today, the CCI is facing criticism from those who view it as an inefficient, toothless, and outdated institution that has failed to keep up with the times. Some industry experts blame the commission for being too “industry friendly”, while others attribute the inefficiency to the government’s failure to provide the commission with an adequate workforce to handle the complex issues it adjudicates.

Earlier this year, startups, including Bharat Matrimony and Shaadi.com, approached the Supreme Court, accusing the commission of “non-adjudication” over their complaints against Google. Meanwhile, although the CCI has traditionally imposed penalties worth crores of rupees, it realised less than 1 per cent of the total amount last year.

“The writing on the wall is that something isn’t right,” says Chawla.

Also read: Chennai startup finds a solution for ‘overqualified housewives’. No more motherhood penalty

‘Digital East India Company’

The latest spate of criticism against the CCI comes from domestic startups that have been up in arms against Google for at least four years. They want the CCI to lend its weight to address Google’s alleged anti-competitive conduct arising from its dominant position in the Android ecosystem and its app store, Google Play.

On 25 October 2022, the commission imposed a penalty of Rs 936.44 crore on Google for anti-competitive practices related to its Play Store policies and issued a list of measures for Google to modify its conduct.

For developers to distribute their apps through Google Play, they were required to accept non-negotiable payment policies. Among other things, Google used to charge app developers 15-30 per cent for listing on the Play Store and using its in-house payment systems. It also mandated that app developers exclusively use Google Play’s Billing System (GPBS) not only for receiving payments for apps distributed or sold through Google Play but also for certain in-app purchases made by users.

After the CCI’s order, Google introduced some changes in its policies and claimed compliance with the CCI’s directives. However, the startups disagreed. While the previous regime charged 15-30 per cent commissions, Google’s new User Choice Billing (UCB) reduced it to 11-26 per cent for paid app downloads and in-app purchases on Google Play.

Right from the beginning, businesses weren’t very comfortable with it (Competition Commission of India), as one can expect. Foreign companies and multinationals were okay because they were used to this kind of thing back home…But for the domestic large companies, which were used to mollycoddling, they started calling it the ‘third mother-in-law’, after RBI and SEBI

— Ashok Chawla, former CCI chairperson

The startups sprung into action instantly, trying multiple routes across various forums, including the Madras High Court, Delhi High Court, and now the Supreme Court. In October 2022, People Interactive India Private Limited, which operates Shaadi.com, approached the CCI with a fresh complaint against Google’s updated payment policies. In April last year, Anupam Mittal, founder of Shaadi.com, called Google the “Digital East India Co” in a tweet and alleged that Google was violating the CCI’s order, tagging CCI’s official handle too.

But startups weren’t going to leave things to chance. Last year, the Alliance of Digital India Foundation (ADIF), a body of startups and app developers, filed a contravention application against Google under Section 42 of the Competition Act 2002, which allows the CCI to inquire into compliance with its own orders. Anybody who fails to comply could be fined up to Rs 10 crore and can also be sent to jail for up to three years if they fail to pay the fine. Incidentally, the ADIF was one of the informants leading to the October 2022 order.

Several startups, including Bharat Matrimony and Shaadi.com, have also ended up in the Supreme Court, accusing the CCI of “non-adjudication” and inaction over their complaints for over 15 months. They had first approached the Madras High Court, which rejected their plea on 19 January this year and asked them to go to the CCI instead. Their petition demands urgent intervention by the Supreme Court, highlighting the “Hobson’s choice” before them—succumbing to Google’s policy, which they call illegal, or exiting the market altogether.

The ADIF and IBDF also approached the Delhi High Court in February this year, alleging that the CCI has not heard their case since July 2023. However, this petition became infructuous when the CCI finally listed their Section 42 application for hearing on 21 February.

While an order on their applications under Section 42 may come any day, the CCI on 15 March finally ordered an investigation into Google for excessive pricing on the Play Store, noting that the tech giant’s UCB payments were “prima facie” violative of the Competition Act 2002. The CCI’s director-general has now been asked to submit its report within 60 days, after which the commission will issue an order.

Meanwhile, the startups remain on edge, especially after Google removed hundreds of apps of Indian publishers like Bharat Matrimony, Shaadi.com, Kuku FM, and Info Edge from Play Store earlier this month. All apps were reinstated within days after Indian startup founders met electronics and information technology minister Ashwini Vaishnaw and minister of state Rajeev Chandrasekhar in separate meetings.

“We have had very constructive discussions and finally, Google has agreed to list all the apps as on the status which was there on Friday morning (March 1), that status will be restored,” Vaishnaw was quoted as telling the news agency ANI.

Also read: IISc deep tech startups are pushing India into elite league. Baby firms with big ambitions

‘Third mother-in-law’

The need for a Competition Commission became urgent after India embraced liberalisation and opened its market to competition from within and outside.

The reforms propelled India onto a high growth trajectory and opened up the markets. However, despite this, the first mention of a competition law came only in February 1999 when then-Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha spoke about the need to shift focus from just curbing monopolies to actively promoting competition. Until then, the country still had the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practice Act 1969—an archaic law designed for the pre-liberalisation era.

The SVS Raghavan committee was appointed to review the competition law and policy, and the Competition Act 2002 was notified in January 2003. By this time, over 80 countries had enacted competition laws, and even a country as small as Malawi had a competition law by 1998 after opening up in the 1990s.

However, the law had a rocky start because it remained stuck in a legal challenge for several years. The CCI became functional with a chairperson and six members only in 2009, and the Indian merger control regime came into force on 1 June 2011.

The law currently bars anti-competitive agreements, prohibits abuse of dominant position by enterprises, and regulates mergers and acquisitions. Over the years, the CCI imposed a Rs 630 crore penalty on real estate developer DLF and Rs 52.24 crore on the BCCI for abusing their dominant positions.

Speaking at the India FDI Forum in Singapore, a day before the merger control regime was to take effect, the former director general of the CCI, Kaushal Kumar Sharma, likened the event to Indian Independence Day.

“At the stroke of midnight, on the intervening night of August 14 and 15, 1947, India gained freedom…The night following today, as the sun sets on this beautiful city nation, will be no different,” he declared, adding that this would bring freedom from anti-competitive practices for India.

Before joining the CCI in 2006, Sharma had served as an IRS officer for more than two decades. He says that he joined the CCI out of his interest to learn a new subject. He was a part of the commission until August 2011 when the groundwork was being laid. He claims to have established the competition law investigation in India and also prepared the merger review format, enabling the commission to finally take wings and become fully functional.

In the initial years, the CCI and its members diligently followed the mandate. The commission has delivered several landmark judgments, with the consumer as its focus. The law currently bars anti-competitive agreements, prohibits abuse of dominant position by enterprises, and regulates mergers and acquisitions.

“Right from the beginning, businesses weren’t very comfortable with it, as one can expect.” says Chawla. “Foreign companies and multinationals were okay because they were used to this kind of thing back home…But for the domestic large companies, which were used to mollycoddling, they started calling it the ‘third mother-in-law’, after RBI and SEBI.”

Over the years, the commission went on to take on several sectors—from imposing a Rs 630 crore penalty on real estate developer DLF and Rs 52.24 crore on the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) for abusing their dominant positions.

Until March 2023, the CCI boasts of having registered over 1,200 antitrust cases and 1,015 merger filings.

Dhanendra Kumar, who was the CCI’s first chairperson, told ThePrint that the merger regulations were a “particularly difficult territory” because the industry had to be convinced about it since they had reservations. He says that at the time, the commission had to undertake considerable advocacy across the country to convince the industry that it would be useful for them because it gives them “legal certainty”.

Any person can file an application before the commission, which then judges if there is a prima facie case. If it finds that there is a prima facie case, the CCI director general investigates and delivers a judgement.

Additionally, any merger or acquisition exceeding the threshold mandatorily requires CCI approval. Until March 2023, the CCI boasts of having registered over 1,200 antitrust cases and 1,015 merger filings.

Akshayy S Nanda, a partner at Saraf and Partners, says that the CCI has been doing a “remarkable job” when it comes to merger control, approving M&A transactions within quick timelines. He especially refers to the system of pre-filing consultation introduced by the CCI, under which parties can engage in informal and verbal consultation with the commission’s officers prior to filing the notice of a proposed combination.

However, Chawla and MM Sharma disagree. Sharma argues that the commission is going “overboard to set up an image of an industry-friendly regulator”.

The CCI has had five full-time chairpersons—all former bureaucrats. In 2018, the Union Cabinet approved the “rightsizing” of the antitrust watchdog, halving its strength to three members from six and a chairperson. This, it said, was being done in “pursuance of the Government’s objective of ‘minimum government – maximum governance’.” However, this has made maintaining a three-member quorum more challenging, leading to the crisis last year.

Experts have also pointed out that most CCI members have been retired bureaucrats, with leaders “who are not familiar with regulation but very comfortable with control.” This was especially visible in the initial years of the commission, which was constantly pulled up by the appellate authorities for violating principles of natural justice. The situation was rectified by the Delhi High Court in 2019, which made it mandatory for a ‘judicial member’ to be present in all final hearings at the CCI.

While retiring in January 2016, Chawla left with hope. In interviews, he said that the implementation of the competition regime was like a “house half-built”, and believed that in the next five years, the CCI will be “fully vibrant”. However, years later, he seems sceptical about his prophecy.

The CCI has had five full-time chairpersons—all former bureaucrats. In 2018, the Union Cabinet approved the “rightsizing” of the antitrust watchdog, halving its strength to three members from six and a chairperson.

Whose fault is it anyway?

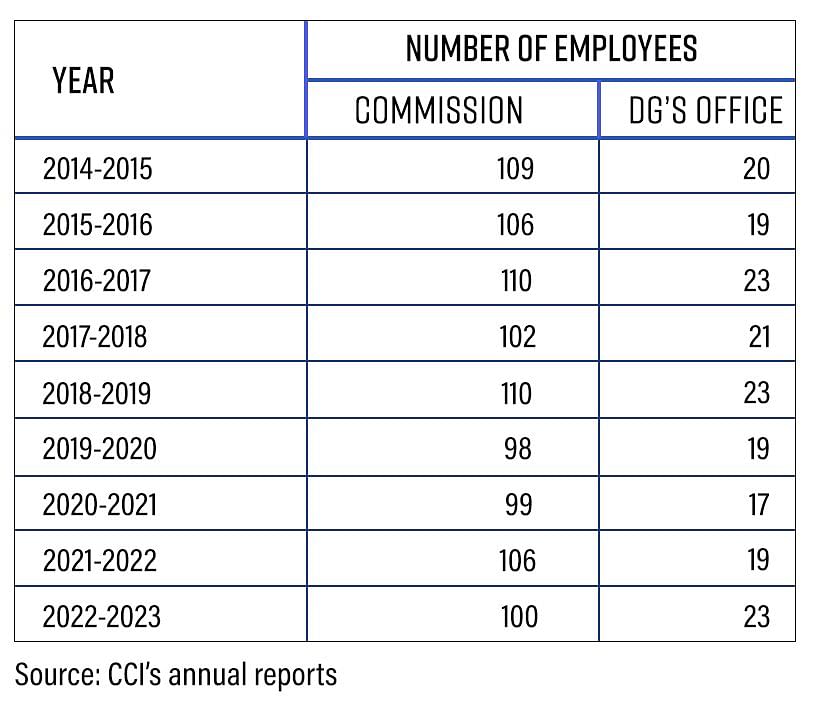

Since 2014-15, the commission has never been at full capacity. Its highest strength was 133—or 67 per cent of its sanctioned capacity—in 2016-17 and 2018-19.

The combined sanctioned strength of the CCI and the DG office is currently 195—with 154 sanctioned posts for the commission and 41 for the DG’s office. This was brought down from 197 during the financial year 2019-20.

Chawla finds it odd that the commission hasn’t been able to “build capacity commensurate with the cases that we are dealing with”, and laments the “step-motherly treatment” it has received from the government. It is this capacity that also worries industry experts about the new proposed Bill—a separate ‘Digital Competition Act’ (DCA) with ex-ante, that is, preemptive, measures to regulate large digital enterprises selectively. The committee has recommended a new law to supplement the Competition Act and “ensure that behaviours of large digital enterprises are proactively monitored and that the CCI intervenes before instances of anti-competitive conduct transpire”. It also recommended that the “CCI’s capacity for technical regulation in digital markets should be strengthened”.

And though the new Bill is a welcome move, many doubt whether the commission has the requisite expertise to take on these tech giants.

“The commission has to augment its capabilities,” says MM Sharma of Vaish Associates.

Since December 2022, the CCI has also been tasked with examining anti-profiteering issues related to GST and examining whether input tax credits availed by any registered person or the reduction in the tax rate have actually resulted in a commensurate reduction in the price of goods or services.

MM Sharma says that the commission’s inability to enforce its own orders—including penalty and market correction orders—substantially impacts its credibility. He blames “clear courtcraft”, with large corporations getting away through stays by the appellate authorities.

Less than 1%

The startups’ struggle isn’t an exception. When the startups were running from pillar to post to get relief earlier this year, the retail traders’ body also wrote to the CCI seeking urgent resolution of the longstanding Delhi Vyapar Mahasangh (DVM) case involving alleged anti-competitive practices of Flipkart and Amazon. The DVM had filed the case in November 2019.

Ashwani Mahajan, the national co-convener of Swadeshi Jagran Manch (SJM), told ThePrint that any delay from the CCI “impacts businesses”. According to him, the CCI’s speed in dealing with cases “depends on who is a part of it”. While he says that its performance has improved in recent years, “there are still issues”. He points out that in Google’s case, the CCI has already passed orders that Google hasn’t complied with.

“The CCI should impose penalties for not complying with its orders,” he asserts.

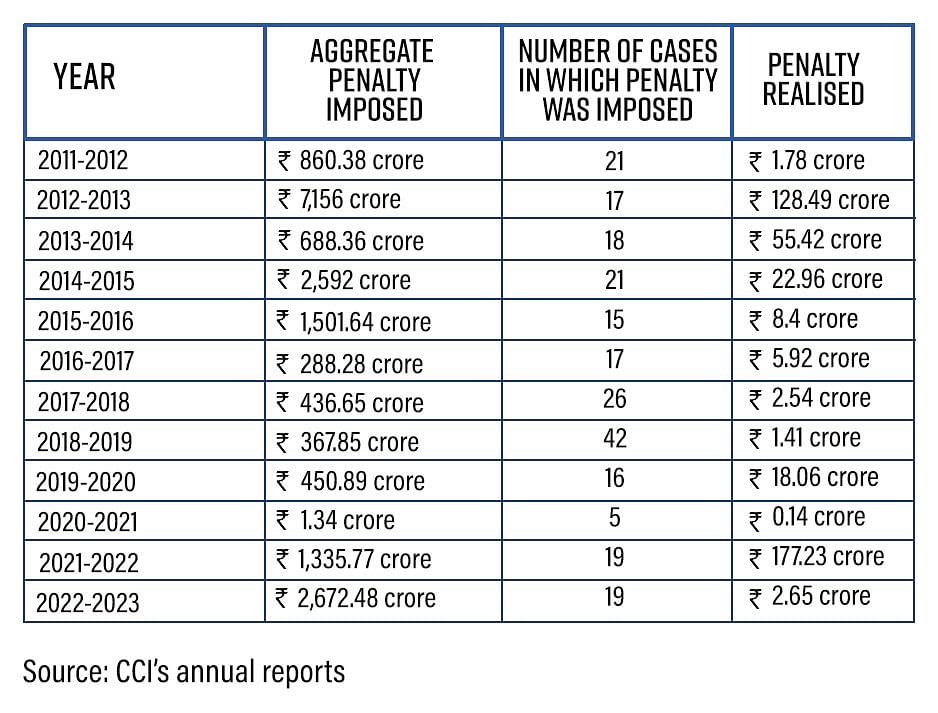

The CCI’s alleged inaction isn’t restricted to the implementation of the measures suggested by it. Data shows that while the CCI imposes penalties worth crores of rupees on violators, it realises only a minuscule percentage. In 2022-23, the CCI imposed a penalty of Rs 2,672.48 crore but was able to realise only Rs 2.65 crore—less than 1 per cent.

MM Sharma says that the commission’s inability to enforce its own orders—including penalty and market correction orders—substantially impacts its credibility. He blames “clear courtcraft”, with large corporations getting away through stays by the appellate authorities.

It’s not that the commission doesn’t have the tools. It can bring an inquiry into compliance under Section 42 “to really hit them hard”. “But the commission waits for the complainant to come forward instead of doing it suo motu…(it is) because of the bureaucratic structure that they have created. It is largely the same set of people who have been in the government for a long time, and they are used to a certain method of working,” says Sharma.

The merger regime has been made so liberal and lenient that it has become something like virtual stamping

— Ashok Chawla, former CCI chairperson

However, Nanda of Saraf and Partners says that it is the appellate authorities—the NCLAT and the Supreme Court—that are to be blamed for the penalties not being realised and the delay in such cases. They get stuck in a judicial logjam for years once appeals are filed.

“If adjudication of cases gets stalled, then what happens effectively is that the company against whom an order is passed continues to indulge in anti-competitive or abusive conduct, penalties lose their deterrent impact, compensation is delayed, and the market continues to suffer meanwhile,” says Nanda.

Ease of doing business

In 2016, then-Finance Minister Arun Jaitley had cautioned that “being pro-business alone is not enough. Being pro-competition is essential.”

Industry experts are certain that the CCI has a pro-business approach. Take the CCI’s merger regime, for instance. Its latest annual report for 2022-23 states that during that year, it received 99 merger filings and disposed of 99 combinations as well.

However, Chawla is of the view that the merger regime in the country has been swept by the philosophy of ‘ease of doing business’.

“The merger regime has been made so liberal and lenient that it has become something like virtual stamping,” he said. His verdict: the emphasis on enforcement or catching violations has been put on the backburner. Not everybody agrees, though. While Kumar argues that the CCI has been doing excelled work “within the constraints that it has been working under”, the major bone of contention is its capacity building, or rather the lack of it.

KK Sharma fondly recalls his 2011 speech in Singapore. He claims that the mention of India gaining freedom brought the audience to tears, but there were some sceptics in the crowd too. “One of the audience members came to me and said, ‘You made us cry, but after all, it (CCI) has government people. It’ll also become like a government department’.”

“I dismissed it then. But unfortunately, he wasn’t too wrong,” he says.

(Edited by Prashant)