New Delhi: Mehrauli Archaeological Park is green, grand, and has one of Delhi’s greatest densities of centuries-old monuments. But most are floundering between neglect, vandalism, administrative turf wars, and a lack of imagination. Hopes for a Sunder Nursery-Humayun’s Tomb-style makeover seem more like a pipe dream.

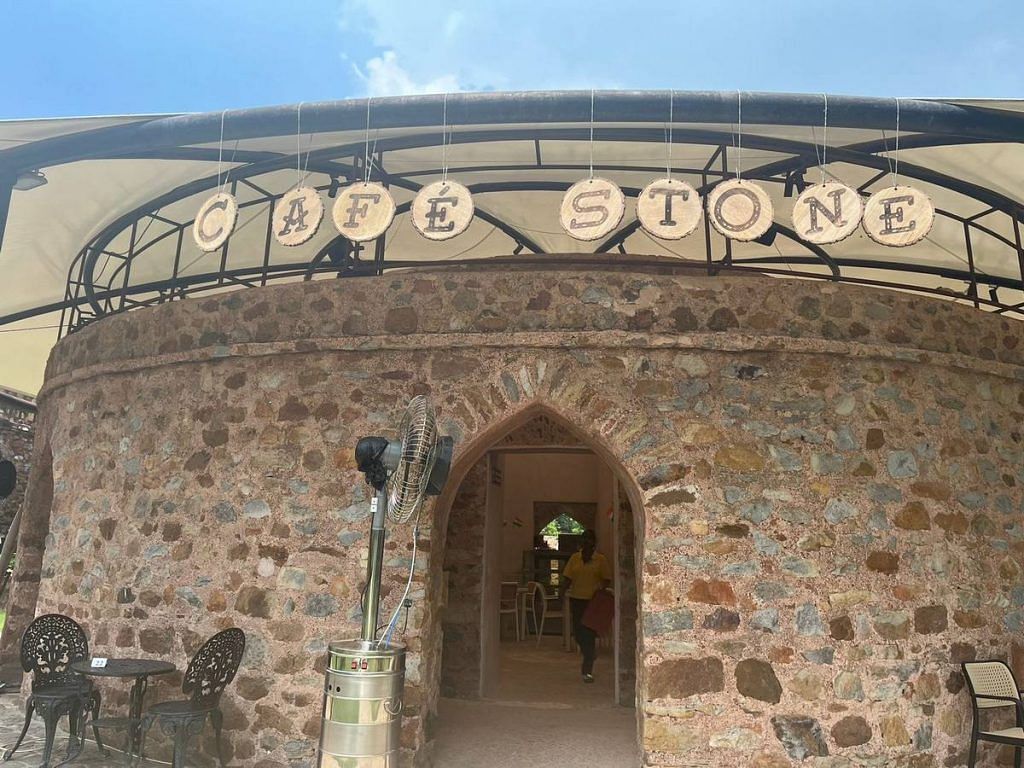

A quick tour reveals evidence only of rush jobs. The inside of Quli Khan’s tomb is painted antiseptic white. Bollywood music blares from Café Stone, once an unnamed monument. A nearby waterbody is a hazardous shade of stagnant green. The reserve forest now comprises manicured lawns, with clusters of flowers and potted plants.

A 5-minute walk away, en-route to the Lodi-era Rajon ki Baoli, a heap of garbage festers, surrounded by crows and cows.

Disparity shapes South Delhi’s Mehrauli Archaeological Park—a 200-acre expanse with dozens of 500-year-old monuments. It’s plagued by administrative hurdles and chaotic ownership, with the Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi Archaeology, the Waqf Board, and the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) all claiming different parts. With little coordination between the bodies and the DDA’s alleged reluctance to be a binding force, it’s far from the oasis it could be, with few visitors or picnic-goers. Rather than complementing the Qutub Minar complex next to it, it has faded into the background like a forgotten cousin.

“The onus is on the DDA. As the overall authority, it needs to create a proper management plan, with the involvement of experts,” said historian Swapna Liddle, former convenor of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), which restored 40 of the park’s monuments from 1997 to 2005. “The ASI, for example, will never look at anything beyond its purview and won’t look at the park as a whole, similar to Delhi Archaeology. We need to look at the park as a whole, and the DDA needs to do it.”

ThePrint has emailed a list of questions to the DDA and Delhi Archaeology; this report will be updated once a response is received.

The park complex contains 55 heritage structures—17 managed by the ASI, 7 by the Delhi Archaeology Department, and the rest by the DDA. The Delhi Waqf Board also claims jurisdiction over certain properties.

Leading up to Quli Khan’s tomb—a memorial to the son of Akbar’s wet-nurse—a precarious faux-wood staircase lined with modern lamp posts greets visitors. The ornamentation continues with white potted plants, another unsettling contrast to the historical setting.

Jamali-Kamali is never going to rival Qutub and its stupendous architecture. Scattered mausoleums and stepwells aren’t going to match up. But they have their own value. Develop it. Make it more inviting. Let people sit around and enjoy themselves.

-Sohail Hashmi, historian

Quli Khan’s tomb falls under the Delhi Archaeology Department, whose approach diverges from the ASI’s preferred methods.

“The idea is not to reconstruct what is lost, but to retain what is there,” said ASI conservation director Sunder Paul.

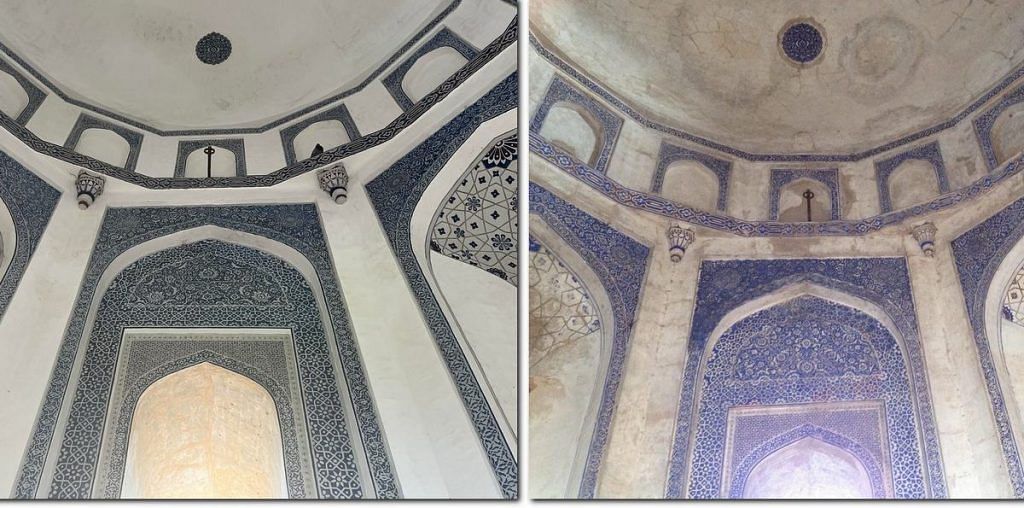

Prior to last year’s G20 summit, the tomb and its surrounding areas were not truly restored but subjected to a hasty patch-up job. An intricate fresco was repainted in a dramatically different shade of blue, and the restoration materials were far from the original.

“Newness is okay. But it needs to be brought back to its original material,” said Liddle. “This area [Quli Khan and Cafe Stone] has been set aside from the park, made into a separate ticketed area.”

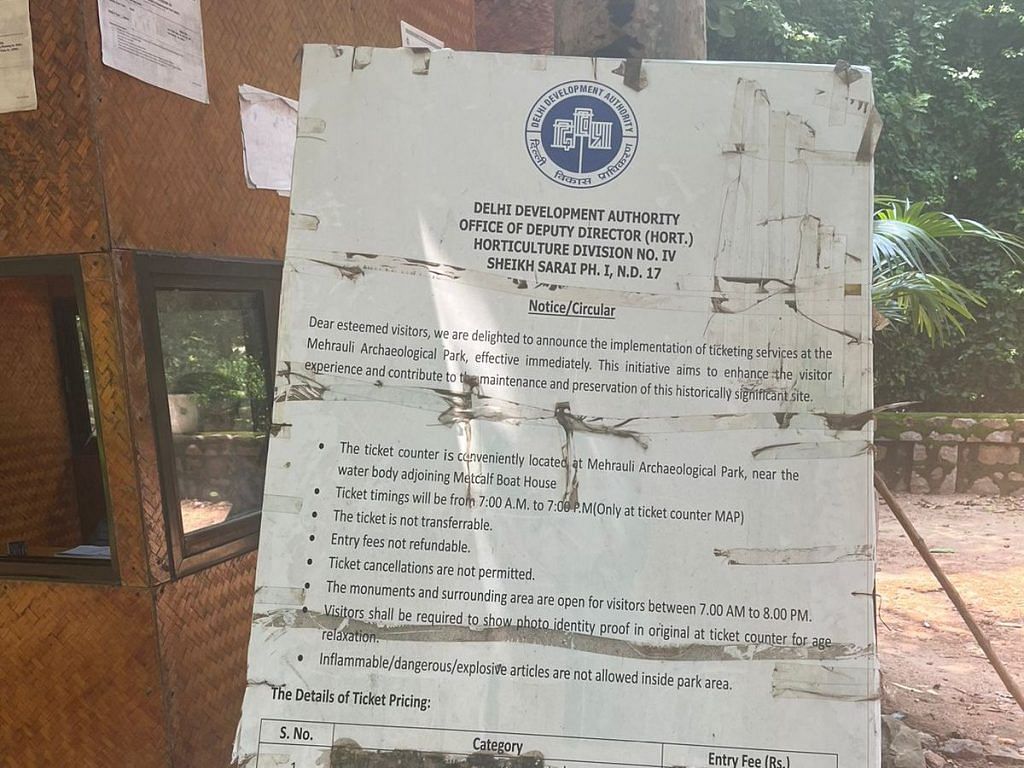

Manned by a security guard lounging in a cracked yellow guardhouse, it now costs Rs 30 to enter this section of the park, which also includes Thomas Metcalfe’s boathouse—a Lodi-era tomb given a British makeover.

Quli Khan’s tomb is empty, save for a lone security guard watching reels on his phone, feet propped against the wall. He moves them only when a visitor approaches.

A large metal signboard trumpets the restoration success of the park, tracing the origins of its “rejuvenation” to an impromptu visit by Delhi Lieutenant Governor VK Saxena during a detour from Qutub Minar last February. Finding the park “more than decrepit,” he initiated the “transformation”. A seven-month multi-agency cleanup job and three visits by the LG later, the authorities have passed the baton back to the public.

“It will now be on the people of Delhi, more than the government departments, to preserve and carry forward this magical inheritance that has passed on to us,” reads the signboard.

While Mehrauli is often seen as a missed opportunity, another Delhi park—Sunder Nursery near Humayun’s Tomb—is credited with having struck the perfect balance.

Also Read: Mehrauli Park conservation is riddled with ownership confusion—needs the Sunder Nursery model

Hidden in plain sight

Having wandered into the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, Monu, a first-time visitor from Amethi on holiday with his wife and two young children, seems bewildered.

Sitting on a bench outside the 16th-century Jamali-Kamali mosque and tomb, he fires off questions: “What is this place? Is it historically significant? Can we go upstairs?”

The red sandstone signage offers some answers, but it’s all in English.

The family stumbled upon the archaeological park after checking out Qutub Minar. Monu wasn’t too impressed by that complex either, but at least he knows it’s “historically significant”.

The Mehrauli Archaeological Park serves as a buffer zone to its more famous neighbour, Qutub Minar, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Historian Liddle argues that a direct pathway between the two could draw in visitors like Monu. But currently a British-era boundary wall separates the complexes.

“Jamali-Kamali is never going to rival Qutub and its stupendous architecture. Scattered mausoleums and stepwells aren’t going to match up. But they have their own value,” said Delhi historian Sohail Hashmi, known for his heritage walks through the city. “Develop it. Make it more inviting. Let people sit around and enjoy themselves.”

Don’t overpower the old and don’t mimic the new. Otherwise, you end up confusing people. You should know which is the old and which is the new

-Swapna Liddle, historian

While the Mehrauli Archaeological Park is low on the average tourist’s priority list, the shared wall is not its only link to Qutub Minar. The key to the sealed Jamali mausoleum is in the custody of the Qutub’s ASI officer-in-charge, according to Hashmi. And getting permission is no mean feat.

The idea behind this lock-up is to keep out vandals and canoodling lovers.

“The best thing to do is to lock up monuments rather than to lose them to vandals,” said ASI’s Sunder Paul.

But when it comes to access, there’s little linking the two heritage sites. Historians stress that the archaeological park needs to be more welcoming and hospitable, rather than overgrown and out of bounds. And somehow this needs to be pulled off without compromising preservation. It’s an endless balancing act, and the park’s caught squarely in the middle.

INTACH is working to attract more visitors, but public awareness is still low.

“We wanted to make people aware of the value of the park, so we developed a heritage trail and initiated the process of conducting walks,” said Ajay Kumar, director of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH). “As individual monuments, they may not have as much historical value. But when you talk about the park as a unit, they gain value.”

For the park’s 2023 makeover, INTACH wasn’t consulted, even though they signed an MoU with Delhi Archaeology in 2008. They aren’t sure why, but Kumar suspects a policy shift about bidding may be to blame.

“Government policies change. INTACH never bids, because then you become a partner and don’t oversee the entire project. Maybe that’s why we were left out,” he said.

The Sunder Nursery way

Monuments governed by Delhi Archaeology open at the crack of dawn. ASI-owned sites, however, don’t allow visitors until 10:30 am. Left scratching their heads at these mismatching schedules are the visitors. On a holiday afternoon, the monuments are largely empty—two families sit at Café Stone, and a couple clicks pictures under a chhatri.

Last year, in the run up to the G20 summit, a roof was added to an unnamed circular monument to create Café Stone. There’s Blue Tokai coffee, weekend pop-ups, and a Margherita pizza priced at Rs 500. The monument’s interiors remain relatively untouched, with garden furniture tucked into the archways.

“You have to make eateries in a style that merges with their surroundings. The bulk of people who go to Mehrauli are poor, lower-middle class people,” said Hashmi. “It’s not only foreign tourists that create spaces.”

Liddle argues that blending in isn’t the only way forward, but she too emphasises that there needs to be harmony between heritage and modern elements.

“Don’t overpower the old and don’t mimic the new,” she said, giving the example of Paris’ Louvre, which added a much-debated glass pyramid-like structure in the 1980s. “Otherwise, you end up confusing people. You should know which is the old and which is the new.”

While Mehrauli is often seen as a missed opportunity, another Delhi park—Sunder Nursery near Humayun’s Tomb—is credited with having struck the perfect balance. Its 90 acres were once home to about a hundred monuments, of which 60 remain, many restored by the Aga Khan Trust.

The trust also renovated the nearby Sabz Burj, the tomb of Humayun’s mother, which sits on the Mathura Road roundabout.

Over the last few years, Sunder Nursery, which costs Rs 100 to enter, has metamorphosed into Delhi’s favourite park, drawing droves of local residents and tourists. It’s almost always filled with picnickers, with the monuments serving as a picturesque backdrop for selfies. There are clean bathrooms, a Sunday farmers’ market, and security arrangements that make it a popular space for women.

“We did certain things right. We got the ASI, the CPWD, and the MCD to sign a single piece of paper, even though they have very different mandates,” said Ratish Nanda, COO of the Aga Khan Trust. “It took two years for us to agree with every single agency.”

Sunder Nursery’s success, Nanda added, is a testament to the key role played by corporate and civil society groups in heritage management. He also emphasised the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between architects, landscape architects, designers, archival researchers, and photographers.

“We had dozens of bilateral meetings with stakeholders. We were meeting with community groups every month,” Nanda said.

Liddle, however, points out that comparisons with Sunder Nursery can only be taken so far since Mehrauli is also an ecologically dense zone, where Nilgai sightings were once common.

Also Read: Mathura culture, Mahabharata Period — ASI digs Govardhan Hill after 50 years

Grand visions & ground realities

The tourism ministry has lofty dreams for Mehrauli Archaeological Park. It envisions films being shot there, a sound and light show dazzling visitors, and the park turning into a lively concert venue. But the ASI has reservations about introducing too much razzmatazz to the site.

“There are always contradictory and conflicting views,” said ASI’s Paul. “The tourism ministry will want its cafeteria. There’s encroachment and illegal construction in the area as well. There are lots of authorities, and we need to strike a balance. But our monuments are in good condition.”

The park’s current big conservation project is the revitalisation of Rajon ki Baoli. For this ASI-owned 16th-century stepwell, the work has been outsourced to the World Monuments Fund (WMF), an international non-profit that has conserved over 700 sites worldwide over the last 60 years.

Architect and conservation consultant Annabel Lopez set the ball rolling project by applying to the WMF’s Watch programme, which identifies heritage sites in need of urgent conservation. With the approval of ASI, Rajon ki Baoli was added to the programme. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) Foundation has also joined hands with WMF as part of their initiative to conserve historic water bodies in India.

While ASI remains the baoli’s custodian, with on-site managers overseeing the process, the restoration is being led by Lopez, WMF, and TCS Foundation.

After detailed architectural documentation, condition mapping, thermal imagery, and a series of tests, the team pieced together what the baoli looked like. But a major challenge came in the form of the tank itself, as it was filled with algae and calcified salt deposits. High-pressure water was used to clean the walls, and the tank had to be drained.

“We removed a lot of silt from the baoli. People had also thrown in pooja offerings and plastic bottles. Organic material had been dumped and also formed silt,” said Lopez. “But now, the water is much cleaner.”

The project is expected to be completed in a couple of months. Next up for Lopez and her team is creating signage for the site. But there’s no clearance for a unified signage system across the park. Some signs overexplain, some under-explain, and some monuments are simply unidentified.

“We don’t need eating spaces, we need information,” Lopez said. “The site would benefit from integrated signage. People want to know more. Delhi needs spaces like Sunder Nursery.”

But before Lopez embarks on the signage project, there’s another urgent challenge to tackle. She’s holding a three-day workshop at the baoli this weekend, and the bathroom is an 8-minute walk away.

There are two options: a porta-potty or hiring an e-rickshaw for the entire day.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)