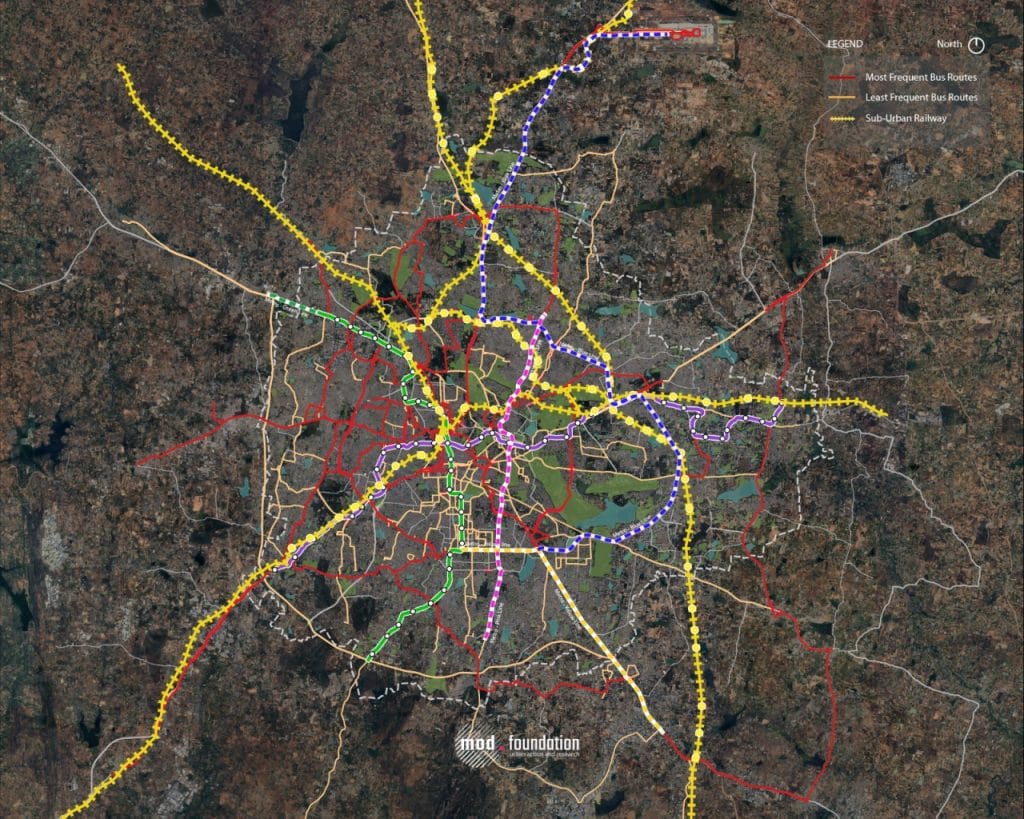

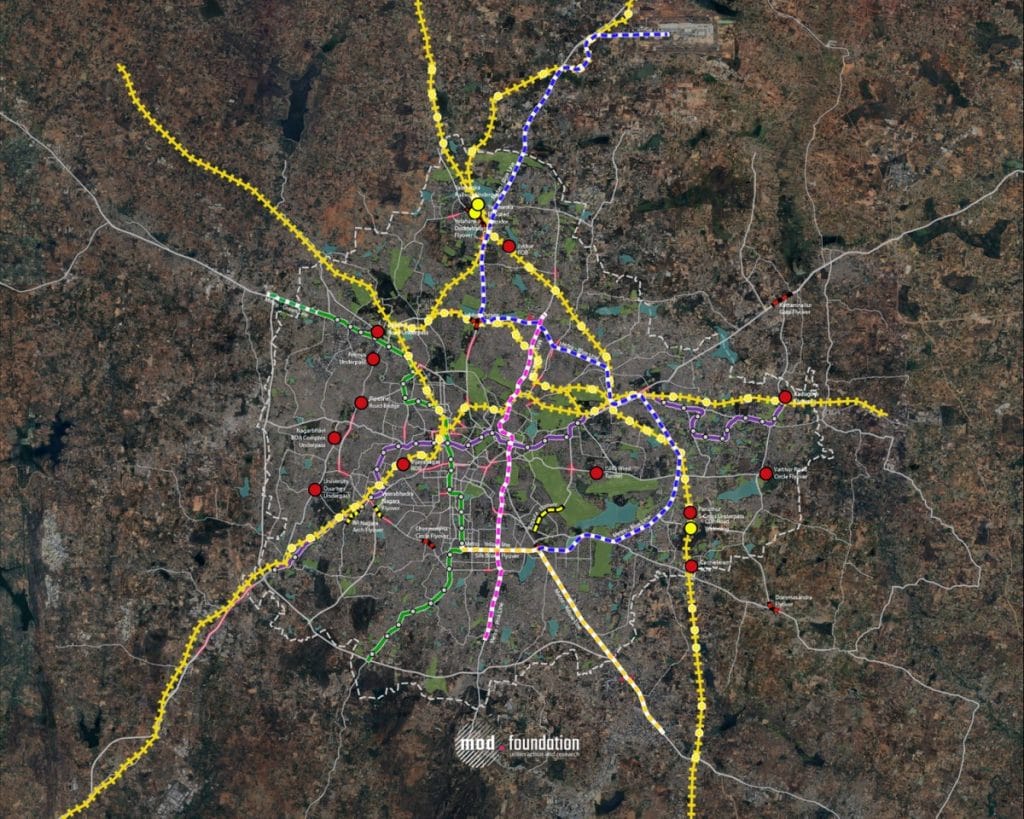

Bengaluru/Hyderabad: The virtual map of Bengaluru covered an entire floor. What stood out most were the missing pieces: 22 unfinished flyovers, an incomplete suburban railway, metro lines that haven’t materialised, patchy road networks. Architect Anvitha Nambiar of the urban action group MOD Foundation pointed it all out, step by step, to residents.

“It’s a call for citizens to take a step back and have a look at the larger picture, and think if the mobility infrastructure being proposed or ongoing is working for us or not,” Nambiar said at a July exhibition on Bengaluru’s transport systems and the projects proposed in the Karnataka government’s 2025-2026 budget.

In Bengaluru, people are either stuck in traffic or obsessing over it. Tech bros and IT aunties constantly discuss it while sipping on lattes and matcha smoothies. Urban planners are putting up exhibitions. Traffic police are turning to AI for help. CEOs are losing patience. Infra failures have become the dark alter ego to Bengaluru’s image as a future-ready IT powerhouse. And Hyderabad is capitalising on it.

In the 1990s, Telugu Desam Party leader Chandrababu Naidu coined the catchphrase “Bye bye Bangalore, hello Hyderabad.” Back then, it was still wishful thinking. Bengaluru had the weather, the MNCs, the momentum. But who has the upper hand is changing. The Indian Silicon Valley vs Cyberabad race was once about attracting the biggest multinationals. Now it’s also about infrastructure, governance, and quality of life—and on all those fronts, Bengaluru is falling behind. Echoes of ‘Bye Bye Bangalore’ are returning to haunt it and leaders are bristling.

Last September, when Union minister Piyush Goyal floated the idea of building a new Indian Silicon Valley, Karnataka IT minister Priyank Kharge shot back: “Bye-bye Bengaluru is bye-bye Bharat.”

Bengaluru is losing talent to Hyderabad, even Chennai and Pune, because of the convenience of working over there. We are a city which has bitten off more than it can chew. Managing time is really difficult. We can’t conduct in-person meetings. Companies are hesitant to expand here

-Keerthan Noble, CMO of Roloway Advertising

The infrastructure bugbear, though, cannot be wished away. Bengaluru is now the third-slowest city in the world, according to the 2024 rankings of Netherlands-based research firm TomTom. The gridlock is not just causing emotional and physical exhaustion, but economic losses. One estimate pegged the social cost at Rs 38,000 crore per year.

“We’re pulling our hair out trying to figure out the traffic situation,” said the CEO of a leading Bengaluru-born app company on the condition of anonymity. He added that if Bengaluru’s governance doesn’t straighten itself, the IT marketplace might shift from the city sooner than anyone is anticipating.

The traffic has degraded the city from ‘pensioner’s paradise’ to a hustle hell. And corporations have started looking for a stairway to heaven. Which might be a one-hour flight away to Hyderabad.

The Telangana capital has been ranked as India’s most liveable city in Mercer’s annual rankings for six consecutive years and even came ahead of Bengaluru in last year’s Hurun India Rich List. In 2024, startup funding saw an over 100 per cent spike from the year before and it’s fast becoming a hub of Global Capability Centres—offshore units set up by large MNCs for critical functions such as IT and R&D.

“In 2014, when Telangana became a new state, Bangalore was three times bigger than Hyderabad in terms of people it employed, number of businesses it had, and other factors. Now, we have narrowed the gap down by 2.1 times on largely four parameters—the number of companies operating out of here, job creation, new companies setting up base, and value of the software developed and exported from here,” said Jayesh Ranjan, Special Chief Secretary (Industries & Commerce) and head of the Congress government’s SPEED (Speedy Proactive Efficient and Effective Delivery) initiative.

“And in terms of Global Capability Centres, we have won the race, there’s no doubt about it.”

Also Read: Rise and fall of India’s BRTS. ‘World-class’ solution that made problems worse

Cyberabad’s day in the sun

Huge hoardings for glossy real estate projects tower near the airport and the Outer Ring Road in Hyderabad. Officials and executives alike speak constantly of expansion, whether it’s offices, startups, or tech corridors.

The tech-industrial township HITEC City, known also as Cyberabad, looks like a showroom of prestigious corporates. Google has its largest India office here, as do Amazon, Microsoft, JP Morgan Chase, to name a few. The roads are neat and spotless.

It’s quite a contrast from Bengaluru’s narrow, dust-laden trafficways. While Hyderabad’s business parks open onto the wide and open Outer Ring Road, Bengaluru’s ORR looks exhausted with jams, potholes, and construction.

“The sense in the industry is to kill Bengaluru,” said a GCC enabler on condition of anonymity. “I don’t think even 20 per cent of the new office spaces being created toward [Bengaluru] airport will be filled easily. Big companies are thinking twice before setting up shop here.”

While Bengaluru’s best days might be behind it, Hyderabad is yet to peak. The heady momentum is palpable.

Hyderabad’s share of Global Capability Centres is expected to grow from 14 per cent to 19 per cent by the end of 2025. But for Bengaluru, it’s projected to drop from 35 per cent to 30 per cent, even as the share of cities such as Delhi, Pune, Mumbai, and Chennai will remain more or less the same.

The phenomenon that Bengaluru has seen over the last 30 years is one of governance trailing growth on a scale far greater than its peer cities such as Ahmedabad, Pune, Hyderabad—even as it has seen faster and greater growth than its peers

-Srikanth Viswanathan, CEO of Janaagraha

Startups are following a similar trajectory. In 2024, Hyderabad saw a 160 per cent growth in startup funding from the previous year, while Bengaluru’s fell by about 24 per cent. Between January 2020 and May 2025, Hyderabad reportedly welcomed more than 2,500 new startups and $2.1 billion in funding.

Much of that is credited to T-Hub, Telangana’s massive public-private incubation centre—one of the world’s largest by area. About 400 startups have launched from here and roughly 200 operate from its premises. It hasn’t produced a unicorn yet, but there are seven soonicorns and dozens of minicorns.

Even though Bengaluru hasn’t lost its status as an innovation epicentre, the infrastructural hassles are beginning to chip away at its appeal for startups.

“Our Bengaluru business is doing well, but growth in Hyderabad is absolutely tremendous,” said Arjun Bhojaraj, chief financial officer at Routematic, a commute management service, at his Indiranagar office. “Traffic issues are playing on the minds of corporates and GCC enablers, who prefer to push GCCs to establish in Hyderabad rather than Bengaluru.”

Hyderabad’s rise is coming at the cost of Bengaluru “for sure”, according to him.

“Unlike earlier, when corporates wanted one big office in Bengaluru, they’re now looking to expand and Hyderabad is the biggest winner,” he added.

Investors, GCC enablers, and entrepreneurs acknowledge Bengaluru’s dominance won’t disappear overnight. But mounting frustration could accelerate the shift.

“Usually, it takes a lot of time for marketplaces to shift. Bengaluru’s networks are strong, and it would take at least a decade to shake,” said the CEO quoted earlier. “But if the issues in this city continue, people will head out within 4-5 years. People wouldn’t want to live here. Quality of life will take precedence.”

Old rivalry

When India’s IT ambitions began rising in the 1990s, Bengaluru and Hyderabad were the two early contenders.

Bengaluru had the head start. It had clement weather, the ‘garden city’ tag, a scientific pedigree through the Indian Institute of Science. PSUs like Bharat Electronics Limited, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, and Hindustan Machine Tools had also set up base in the city, laying the groundwork for an engineering and research culture well before the software boom.

Hyderabad had similar ingredients. It was home to the defence-focused PSU Bharat Dynamics, the Electronics Corporation of India, a manufacturing unit of HMT. Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, set up in 1972, gave it a strong engineering pipeline.

But the Karnataka government moved faster. In 1978, it earmarked 332 acres for an industrial hub that would become Electronic City. In the 1980s, Infosys and Wipro moved operations to Bengaluru from Maharashtra. Then came the clincher: in 1985, Texas Instruments set up India’s first multinational R&D centre to design semiconductors in the city.

This was a major missed opportunity for Hyderabad, according to Telangana Special Chief Secretary Jayesh Ranjan.

“Texas Instruments also approached the government in Hyderabad about setting up an office. But the officers and leaders of that time were not responsive. Karnataka’s response was far better,” Ranjan said.

By the time SM Krishna became Karnataka chief minister in 1999, Bengaluru was already on a roll. One of the state’s most tech-forward leaders, he built on this by teaming up with Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani to launch the Bengaluru Agenda Task Force (BATF), a public-private initiative to improve city infrastructure and attract business, which was functional until 2004.

We have invested quite a lot in improving our talent quotient. One of the reasons the gap between Bengaluru and Hyderabad was widened was the perception that more technically qualified people are there in Bengaluru. We have bridged this

-Jayesh Ranjan, Telangana Special Chief Secretary (Industries & Commerce)

Meanwhile, Hyderabad got its own tech and industry flagbearer in Chandrababu Naidu, who became CM of undivided Andhra Pradesh in 1995. With his drive to wrest Bengaluru’s crown, he was called the CEO CM. He aggressively courted global tech firms and CEOs as part of his ‘Bye Bye Bangalore, Hello Hyderabad’ pitch, and inaugurated Cyberabad in 1998, with generous land allotments and infrastructure support. Naidu’s much-publicised lobbying with Bill Gates in the late 1990s, which led to a Microsoft development centre in Hyderabad, was another milestone that boosted the city’s profile.

But as the two cities chased the IT gold rush, Bengaluru took a clear lead. By 2010, it had about 35 per cent of the Indian IT industry’s market share, while Hyderabad accounted for about 15 per cent. Corporate Bengaluru grew from 500 companies in 1995 to more than 5,500 today.

Beneath the shine of startups and billion-dollar valuations, though, there were cracks. Part of this was due to lack of political advocacy and lacunae in the way the city is governed.

No political boss for Bengaluru

For nearly a decade, the previous Telangana Rashtra Samithi (now Bharat Rashtra Samithi) government made Hyderabad a top priority. KT Rama Rao, son of former Chief Minister K Chandrashekar Rao, oversaw both the IT portfolio and urban development from 2014 to 2023. He regularly pitched the city to global investors and would one-up Bengaluru at every chance he got.

When Housing.com CEO Rahul Yadav tweeted in 2022 that “rural India had better infrastructure than India’s Silicon Valley”, KTR quickly replied: “Pack your bags & move to Hyderabad! We have better physical infrastructure & equally good social infrastructure.”

That kind of assertive political backing is something Bengaluru hasn’t had for a while, according to Srikanth Viswanathan, CEO of Janaagraha, a nonprofit that focuses on improving quality of life in cities.

After SM Krishna, he said, there hasn’t been a focused champion for the city, except the current Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar, who also holds the portfolio of Bengaluru City Development, including the municipal corporation and other related bodies. He is often referred to as a “de facto mayor” but the long-term absence of a political cheerleader has contributed to the city becoming a mismanaged quagmire.

“The phenomenon that Bengaluru has seen over the last 30 years is one of governance trailing growth on a scale far greater than its peer cities such as Ahmedabad, Pune, Hyderabad—even as it has seen faster and greater growth than its peers,” Viswanathan said.

One aspect of that is inadequate representation in the state legislature. Bengaluru contributes 36 per cent to Karnataka’s economy, but has a meagre presence in the assembly, with just 29 out of 224 seats—about 13 per cent. Hyderabad, by comparison, has 24 out of 119 seats in Telangana (around 20 per cent), with delimitation expected to raise that to 35 after the 2025 census.

The problem with Bengaluru is that we don’t have satellite towns. We did try to create the satellite towns of Kengeri and Yelahanka, but what happened was that the growth was so fast that satellite towns became part of Bengaluru

-A Ravindra, former chief secretary of Karnataka

Local governance hasn’t fared much better. The municipal body, Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), hasn’t held elections since 2015 and is currently run by a state-appointed administrator. The city’s mayor serves just a one-year term, in contrast to Hyderabad’s five-year tenure.

“Bengaluru’s urban planning and design is completely broken, if not non-existent, because of severely fragmented governance systems and no fixed accountability for outcomes. What Bengaluru needs is an empowered mayor with a five-year term,” Viswanathan said.

The BBMP, he argued, became an unwieldy giant with one chairperson presiding over the whole city. Several government agencies with overlapping or conflicting responsibilities made governance chaotic. Funding and staff shortages only add to these woes.

“Bengaluru’s municipal area is more than 700 square kilometres, its roads are 12,000 kilometres, which makes it among the largest municipalities in the country. For this, we have always had a budget of around Rs 14,000 crore and only 30,000 employees,” he said.

The overall BBMP budget for 2025-26 was over Rs 19,000 crore, with an allocation of Rs 14,249.98 crore for public works. But it’s still modest compared to that of some other major cities. Mumbai’s BMC, for instance, has a budget of Rs 30,000 crore and nearly 1,50,000 employees for an area of 437 square kilometres. In May, the Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA) officially replaced the BBMP. The city will be divided into five corporations, with elections expected at the end of the year.

Namma Bengaluru is now Greater Bengaluru!

As the city grows, so does our vision for its future.

Introducing the new face of Bengaluru:

5 Corporations. 1 City. 1 Bold Vision.

For the first time, Bengaluru will have a decentralized and citizen-first governance model that is built… pic.twitter.com/8Hum6Xgb0K

— DK Shivakumar (@DKShivakumar) July 23, 2025

As for Hyderabad, it has had political favour right from Chandrababu Naidu to KTR. The current Special Chief Secretary, Jayesh Ranjan, also held the charge for developing the state’s IT sector for about a decade and is now also in charge of Telangana’s Investment Cell. The city has also had Vijayalakshmi Gadwal as mayor since 2021. The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC), unlike BBMP, has maintained more continuity in its civic leadership.

The GHMC has also done better on sanitation. Hyderabad received a 7-star rating and was declared the sixth cleanest city in the 2024 Swachh Survekshan Mission survey for cities over 10 lakh population—its best-ever performance. Bengaluru ranked 36th in the same survey.

Not just traffic, but flooding and waste management are chronic issues in Bengaluru. This buckling infrastructure has been increasingly souring the mood of business leaders.

Back when KTR invited CEOs to move to Hyderabad, Nikhil Kumar, co-founder of Setu API, rued the “mess” that Bengaluru had become.

“Please take note sir @CMofKarnataka—if you don’t fix this, there will be a mass exodus!” he posted.

That is yet to happen, but what was once a competition for MNCs to set up base is now a full-on war over whose infrastructure is better.

Blocked arteries, ‘Stonehenge’ infra

On a Saturday night this July, EaseMyTrip co-founder Prashant Pitti was stuck for over 100 minutes on Bengaluru’s infamous Outer Ring Road. Frustrated, he fired off a post on X, pledging Rs 1 crore to anyone who could use AI to map all of the city’s choke points and share the data with traffic police. He’s since made it his mission to ease everyday commuting in Bengaluru.

“Meetings get missed, people come late to office. A lot of plans just remain plans because there’s always this fear of going 20 kilometres away in Bengaluru,” Pitti told ThePrint. “The only day with any respite is Sunday.”

The usual suspects are unchecked urbanisation and a car-first road design. But the city has suffered so far not from growth but a crisis of imagination and an inability to change.

No major Indian city is immune to traffic problems. Eight of the world’s fifty slowest cities are in India. But ambitious Bengaluru, in particular, is bursting at the seams due to poor planning that never kept pace with its own expansion.

The city has seen breakneck growth since the 1970s, with the population rising by 59 per cent between 1971 and 1981, and by 38 per cent between 2001 and 2011.

Successive governments failed to plan how a growing population would move across the city. Unlike other metros, Bengaluru never developed self-contained satellite towns.

“The problem with Bengaluru is that we don’t have satellite towns. We did try to create the satellite towns of Kengeri and Yelahanka, but what happened was that the growth was so fast that satellite towns were no longer satellite towns. They became part of Bengaluru,” said A Ravindra, who retired as chief secretary of Karnataka in 2022 and is also an urban policy expert.

Compared to other cities, Bengaluru’s road network also trailed way behind.

Data from the Asian Development Bank’s Urban Transport Profile shows that Delhi had a built-up road network of 31,000 km in 2010, serving a population density of 14,160 people per sq km (2019). Bengaluru had just 14,000 km of roads as of 2018, despite a higher population density of 15,595. Hyderabad had a total road network of 9,000 kilometres as of 2019.

The layout of the roads left much to be desired as well.

“Bengaluru, historically a market town, grew radially on all sides, and you start to have these rings around the city. It has arterial roads that take traffic out of the city. But there are not a lot of roads for people to move from one neighbourhood to another within the city,” said Amritha Ganapathy, senior urban planner at MOD Foundation.

Urban mobility is a complex system, a classic domain of complexity science. Two decades of road interventions have not borne any fruit

-Ashish Verma, professor of Transportation Systems Engineering at IISc

She added that infrastructure around IT parks came too late, and job growth projections were never factored into planning. As a result, the new areas of Bengaluru became a “clinical experience”—devoid of local markets, parks, and other public spaces.

An analysis by urban data platform OpenCity shows that central Bengaluru, the old part of town, has dense road coverage, but it thins near BBMP boundaries, including around commercial centres. Mahadevapura, home to an IT hub, has one of the worst road densities in the city.

Bengaluru’s arterial roads have also become commercial hubs, worsening congestion.

“Major arterial roads such as Tumkur Road, Hosur Road, Old Madras Road, ITPL Road (Mahadevpura), Mysore Road routinely witness traffic chaos,” noted a 2020 KnightFrank report. “The purpose of big radial roads should be to serve long-range connectivity and that alone. However, in the given scenario, they also serve as commercial/business roads, parking lots, and residential access roads which lead to traffic bottlenecks in the peripheral areas.”

The report highlighted that per the city’s Revised Master Plan 2015, just 7 per cent of land was allocated for transport and communication—far short of the recommended 20 per cent.

Unfinished infrastructure projects add to the mess. In its exhibition ‘Under Construction: Bengaluru’ last month, MOD Foundation documented several such decaying structures, including the Ejipura flyover, dubbed the ‘Stonehenge flyover’ for its monolith-like pillars that lead nowhere.

Yet even with unfinished business blocking Bengaluru’s arteries, the state government has kept grasping for the same old ‘fix’.

Pushback on ‘Brand Bengaluru’ plans

The latest Karnataka budget aims to revive ‘Brand Bengaluru’ with a slate of big-ticket infrastructure projects, many of which are now facing heat from opposition leaders and citizen groups.

These include Rs 8,916 crore for a double-decker flyover alongside Namma Metro Phase 3, a tunnel road from Hebbal to Silk Board, and 300 kilometres of new roads to be built using buffer zones along canals. There’s also Rs 27,000 crore allocated to the long-delayed Peripheral Ring Road. The budget also mentions building tier-2 and tier-3 cities “to reduce pressure” on Bengaluru, but offers no specifics.

The tunnel road, in particular, has drawn plenty of flak. Bengaluru South MP Tejasvi Surya warned it would only worsen gridlock.

“The CM and Deputy CM have come up with an Rs 18,000 crore tunnel road project from Hebbal to Silk Board. But this is only going to aggravate the problem. Many studies, including by IISc, said the tunnel road will only increase private vehicles, and in a short time, this road too will be chock-a-block,” he said in a YouTube video.

Digging tunnels in Bengaluru is difficult and expensive since the city sits on granite, difficult to pierce through.

Meanwhile, public transport is languishing even as new cars keep hitting the road. The city now has 1.2 crore registered vehicles—around 37 per cent of all registered vehicles in Karnataka. The bus fleet, meanwhile, has fallen from 6,502 buses in 2021 to 6,102 in 2023-24. Routes have been reduced as well, from 2,263 in 2018-19 to 1,756 in 2023-24.

The current crop of solutions has not impressed Ashish Verma, professor of Transportation Systems Engineering at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). What is lacking, he noted, is systems-level thinking that links urban mobility to broader goals like livability.

“Urban mobility is a complex system, a classic domain of complexity science. Two decades of road interventions have not borne any fruit,” he said.

As Bengaluru wrestles with its legacy problems, Hyderabad is presenting itself as the future.

Hyderabad’s winning pitch

Vishwanadh Raju, who built a 22-year career in talent acquisition with global multinationals, now heads his own business in Hyderabad and is building traction by roping tech companies into the city.

“Hyderabad has a substantial edge when it comes to infrastructure, policies and growth,” said Raju, not the founder and CEO of PlugScale, which helps launch and scale GCVs. “Many global companies are waiting to enter the city — it will attract more companies than any other city.”

Raju is hoping to steer more and more companies to Hyderabad, a city whose potential, according to him, has only just begun to unfold.

GCC leaders also point to its rich talent pool.

“We are leveraging Hyderabad’s strengths, particularly its rich STEM talent pool, to accelerate science and solve complex challenges using digital technologies like AI and ML,” said Naveen Gullapalli, managing director, Amgen India. “Hyderabad’s energy and commitment to progress resonate with today’s workforce, particularly those in life sciences and technology.”

It’s a sentiment Telangana officials echo with pride. Ranjan leans back in his seat and smiles widely when talking about Hyderabad’s growth spurt. He is bullish about the city’s prospects.

Hyderabad’s urban infrastructure has grown significantly, especially in key business districts. The expanding metro network, improved road connectivity, and new commercial developments have made scaling operations easier

-Matthias Schacke, country head, India Service Company, UBS

“We have invested quite a lot in improving our talent quotient. One of the reasons the gap between Bengaluru and Hyderabad was widened was the perception that more technically qualified people are there in Bengaluru. We have bridged this,” Ranjan said.

The state has overhauled college curricula to match industry needs, introducing subjects like AI, machine learning, and cyber-security into BTech courses this year. The idea is not just to grow talent, but to retain it.

“People willingly move to Hyderabad for work because of its cosmopolitan vibe, HITEC City, and growing opportunities,” said Mohith Mohan, CEO of Moar Advisory Services, which helps businesses scale and optimise operations.

Real estate developers in Hyderabad say demand is now outpacing supply for office space.

Multinational companies, too, are warming to the city’s promise. For some, Hyderabad’s focus on infrastructure and traffic control has been a deciding factor. Swiss banking major UBS, for instance, is expanding its GCC in Hyderabad and plans to hire an additional 1,800 employees in the next couple of years.

“Hyderabad’s urban infrastructure has grown significantly, especially in key business districts,” said Matthias Schacke, country head, India Service Company, UBS, in an email response to ThePrint. “The expanding metro network, improved road connectivity, and new commercial developments have made scaling operations easier… Continued focus on transport integration and easing congestion will help the city keep pace with rising demand.”

But things are not all hunky dory in the city of Nizams.

Also Read: Bengaluru billionaires are changing Indian philanthropy. Old-style CSR is out

Is Hyderabad really the ‘better Bengaluru’?

On a July Friday evening, heavy rain flooded Hyderabad’s Nayani Narasimha Steel Bridge, leaving commuters stranded and cabs impossible to find. Water reached knee height in some parts.

“Ye roz ka hai (This is a regular thing),” said an IT worker waiting under an umbrella for her auto. “Everyone thinks Hyderabad is the better Bengaluru. But in reality, both cities are equally bad.”

For years, Hyderabad has branded itself as a sunnier, smoother Bengaluru. But without proper planning, many fear it may be headed down the same potholed path.

If Bengaluru is the third slowest city in the world, Hyderabad isn’t that far behind—it ranked 18th on the TomTom Index. The average travel time to cover a distance of 10 kilometres in Bengaluru was 34 minutes, according to the index, while for Hyderabad it was 32 minutes. But Bengaluru’s roads also became slower by almost 50 seconds in the span of a year.

Public transport in Hyderabad has its own gaps— while HITEC City boasts low-floor electric buses that are free for women, the city’s total fleet is only 3,100.

Telangana officials, however, say infrastructure upgrades are well underway. Ranjan insisted that the basic difference between Bengaluru and Hyderabad is the latter’s ‘proactive’ approach to infrastructural development.

“Even when we built the ORR, we were told we didn’t need an 8-lane expressway. But now it is the pride of Hyderabad,” he said. “We are building new flyovers, widening roads, and diffusing our IT parks to other ends of the city.”

Road expansion and flyover projects are planned for areas like KBR Park, Jubilee Hills, and Khajaguda. But the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC), which spans roughly the same area as Bengaluru’s BBMP, runs on a much smaller budget of Rs 8,440 crore. With just 4,500 permanent staff and 25,000 contract workers, its capacity is limited.

Still, the prevailing sentiment is that the city has time to course-correct.

“Hyderabad is where Bengaluru was in the early 2000s. Till then, mobility in Bengaluru was far simpler,” said Keerthan John Noble, CMO of Bengaluru-based Roloway Advertising. He added, however, that Hyderabad might still avoid the same fate if it takes the right precautions in the next 10-15 years.

“Bengaluru is losing talent to Hyderabad, even Chennai and Pune, because of the convenience of working over there. We are a city which has bitten off more than it can chew,” he said. “Managing time is really difficult. We can’t conduct in-person meetings. Companies are hesitant to expand here.”

Yet many Bangaloreans aren’t ready to concede defeat. Any comparison with Hyderabad elicits fierce local pride—about the culture, the climate, the restaurants.

“The support Bengaluru has for science and technology is very difficult to replicate in any other city,” said oral historian Roopa Pai. “We’ve always been a forward-looking, science-oriented city.”

Noble agrees that Bengaluru remains a great place to start up. But it’s no longer the best city to scale up. The creaking infrastructure gets in the way.

“It is a nice place to incubate new businesses, but to develop them, it is not an ideal space any longer,” he said. “New business means a lot of moving around and Bengaluru doesn’t provide that opportunity.”

This is the second article in Urban Pressure, a series on how bad planning is choking Indian cities.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)