Gaya: At the holy site synonymous with Buddhist enlightenment, a heated argument is underway these days. Not about peace or worldly suffering. But about Jawaharlal Nehru and Bakhtiyar Khilji.

“It is Poorva Buddha and Bodhisattva idols,” say the Buddhists. “It is the Pancha Pandavas with Maa Kunti,” counter the Hindus. “It is because Nehru and Gandhi promised we would get the temple in its entirety,” claim the Buddhists. “It is because the great leaders of this country decreed that four Buddhists should be part of the committee,” insist the Hindus. “After Bakhtiyar Khilji’s invasion, it was the Hindus who protected it, who kept it standing,” argue the Hindus. “But there were not enough Buddhists left to care for it,” concede the Buddhists.

All the arguments boil down to one question: Who owns the Mahabodhi Temple in Gaya?

That’s how history is being reinterpreted in Bodh Gaya, the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment. The city now stands at the heart of relentless battle over its most sacred site—the Mahabodhi Temple. Tensions are rising between Hindus and Buddhists, each staking their claim to the temple’s history and identity. At the core of it all lies the Bodh Gaya Temple Act of 1949—a law that determines who controls the holiest shrine in Buddhism.

Both India and China have carefully and proactively used the “Buddhist card” to strengthen ties with Buddhist-majority countries.

Professor Hemant Adlakha, Associate Professor at JNU and an expert in Chinese and South East Asian Studies

The tensions between Buddhists and Hindus in Gaya are both unfortunate and ill-timed. India is the land of the Buddha’s birth and enlightenment—but allegations of Hindufying Buddhist Gaya can hurt India in the race with China over Buddhist diplomacy in the region. Over the past two decades, Beijing has surged ahead in using Buddhism to expand its influence across the subcontinent. It has funded the restoration of Buddhist sites and pilgrimage trails in Lumbini, Nepal, and supported clergy in Sri Lanka.

Hemant Adlakha, an Associate Professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and expert in Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, emphasised the growing geopolitical significance of Buddhism in India–China relations.

“At the outset, neither India nor China are officially Buddhist states, but Buddhism plays a subtle yet crucial role in their diplomatic strategies. Both nations have carefully and proactively used the “Buddhist card” to strengthen ties with Buddhist-majority countries in South and Southeast Asia—such as Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Thailand—where recent developments have made this engagement even more relevant,” he said.

Over the years, Buddhism has re-emerged as a key element in cultural diplomacy across Asia. From a domestic standpoint, India must remain mindful of the diplomatic implications of this resurgence.

Since becoming Prime Minister in 2014, Narendra Modi has placed special focus on Buddhism, participating in Buddha Purnima celebrations and making efforts to foster harmony around India’s Buddhist heritage. Notably, during Xi Jinping’s 2014 visit to India, Modi mentioned the first Chinese monk who had traveled to Gujarat in the 7th century—a historical connection that paved the way for his visit to China the following year, where he received a grand welcome in Xi’an, an ancient capital located 1,200 km from Beijing.

Considering the global ramifications, the fight for the temple’s ownership between Hindus and Buddhists holds much significance and urgency.

For years, court battles have swung between opposing sides. “The Calcutta High Court ruled—it belongs to the Hindu Math,” say the Hindus. “No, the temple belongs to the Buddhists,” say the Buddhists, interpreting the verdict in their favour. Politicians, such as former AAP MLA Rajender Pal Gautam, Supreme Court lawyers, ex-members of the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee, representatives from monasteries in Gaya, and groups such as the Bheem Army are digging deep into archives, searching through books, and revisiting history to find out who owns the temple’s legacy.

Buddhists are angry

Under the banners of the AIBF and All Buddhist Organizations, Lama is leading a fresh wave of protests, reviving a demand first raised more than three decades ago.

Since 12 February, thousands of Buddhists have been marching to Bodh Gaya, joining an indefinite hunger strike in their fight for exclusive control over the Mahabodhi Temple.

“We demand full control over the administration of the temple and the abolition of the Bodh Gaya Temple Act of 1949,” announced Akash Lama, the general secretary of the All India Buddhist Forum (AIBF), into the microphone, addressing hundreds of protestors who have joined the Mahabodhi Mandir Mukti Andolan.

Under the banners of the AIBF and All Buddhist Organizations, Lama is leading a fresh wave of protests, reviving a demand first raised more than three decades ago.

The last major protest for this cause was staged in 1992.

“After two and a half years of intense protests, the movement lost momentum and eventually faded by the 2000s,” he said. But this time, the Buddhist community has come prepared, determined not to repeat the mistakes of the past.

“Our past failure lay in the absence of Himalayan Buddhists’ participation,” Lama said. He explained that the earlier movement had become dominated by Maharashtra and was later consumed by the political infighting of various factions. “But this time, things are different,” he claimed. “The Himalayan Buddhists are stepping forward.”

Lama, who calls himself a son of the Himalayas, is from Darjeeling.

For the past decade, he has been meticulously laying out the foundation for this movement.

He recalled how, in March 2016, he led a peaceful demonstration—the Buddha Peace Rally—in Siliguri, West Bengal. That rally had led to a significant breakthrough—the state officially declared a holiday on Buddha Purnima.

“Buddha Purnima is a gazetted holiday in India, yet many states—including Punjab, Telangana, and Mizoram—do not declare it a state holiday. Previously, even West Bengal had overlooked it. But now, our efforts have borne fruit,” he said.

The otherwise reclusive and inward-looking community of Buddhists is now on a mission. There isn’t a door they haven’t knocked on in the last eight years. They have followed the quintessential playbook of mobilisation and activism.

“I have lost 20 kilograms, and our people from places such as Ladakh can’t endure this scorching heat any longer—yet there has been no dialogue from the government,” Lama said.

Since 2017, Lama has been on a journey across India, visiting communities, listening to their voices, and trying to understand whether the Buddhist population stood united on this cause.

“We gained the support of Samta Sainik Dal (SSD), Rashtriya Bodh Mahasabha, Jai Bheem Mission, and many others,” he added.

The first formal meeting for the hunger strike had been planned in 2021, though the pandemic had delayed it by two years. That same year, a delegation met with the Minority Commission of India, presenting their demands.

Then, in June, over 50,000 Buddhists took to the streets across 22 states, submitting memorandums to District Magistrates.

“We’ve submitted petitions to DMs, the Chief Minister, and even the Prime Minister,” Lama stated.

In 2024, the Minority Commission invited them for dialogue.

“We were promised that the commission would get the Chief Minister of Bihar on board with our demands,” he said. What followed was a chain of meetings in Aurangabad, Mumbai, Patna and Kolkata. And finally, in November 2024, 40,000 Buddhists gathered in Patna’s historic Gandhi Maidan, declaring their intention to begin a hunger strike.

By 26 April, the hunger strike had entered its 74th day.

“I have lost 20 kilograms, and our people from places such as Ladakh can’t endure this scorching heat any longer—yet there has been no dialogue from the government,” Lama said.

He said that their last meeting with the additional secretary in the Home Department, IAS Animesh Pandey, took place on 27 February at Patna’s Patel Bhawan. That same night, Lama claimed, the Gaya police forcibly removed the protestors who were demonstrating outside the temple.

The issue also reached the Indian Parliament, when MPs such as Chandrashekhar Azad and Prof. Varsha Eknath Gaikwad called for the repeal of the Bodh Gaya Temple Act. They argued that the current composition of the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee is fundamentally unjust, denying Buddhists the constitutional right to manage their own religious affairs.

Minister of State for Social Justice and Empowerment Ramdas Athawale also visited the protestors in Gaya a month ago. He later met Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, urging him to support the repeal of the 1949 Act. Athawale has promised his full support for the movement and announced plans for a large-scale demonstration in Delhi.

Though this has given national attention to the movement, so far, there has been no significant response from the state on the matter, except for comments from the District Magistrate IAS Dr. Thiyagarajan S.M. He confirmed that two rounds of discussions have taken place—one at the district level and another at the Home Department level.

“Their demands have been officially recorded. Since the issue concerns the Act, it will be handled at the Home Department level,” he told ThePrint.

Also read: Buddhist viharas were sites of business. They weren’t just ‘monasteries’

Hindu Math vs Buddhist Monks

It is out of our large-heartedness that the Buddhists have been able to use Jagannath Temple’s land to create an entrance for the Mahabodhi Temple,” acting Mahant of Bodh Gaya Hindu Math said.

On the surface, it appears to be all about “bhaichara“—brotherhood—between the two communities until cracks begin to show.

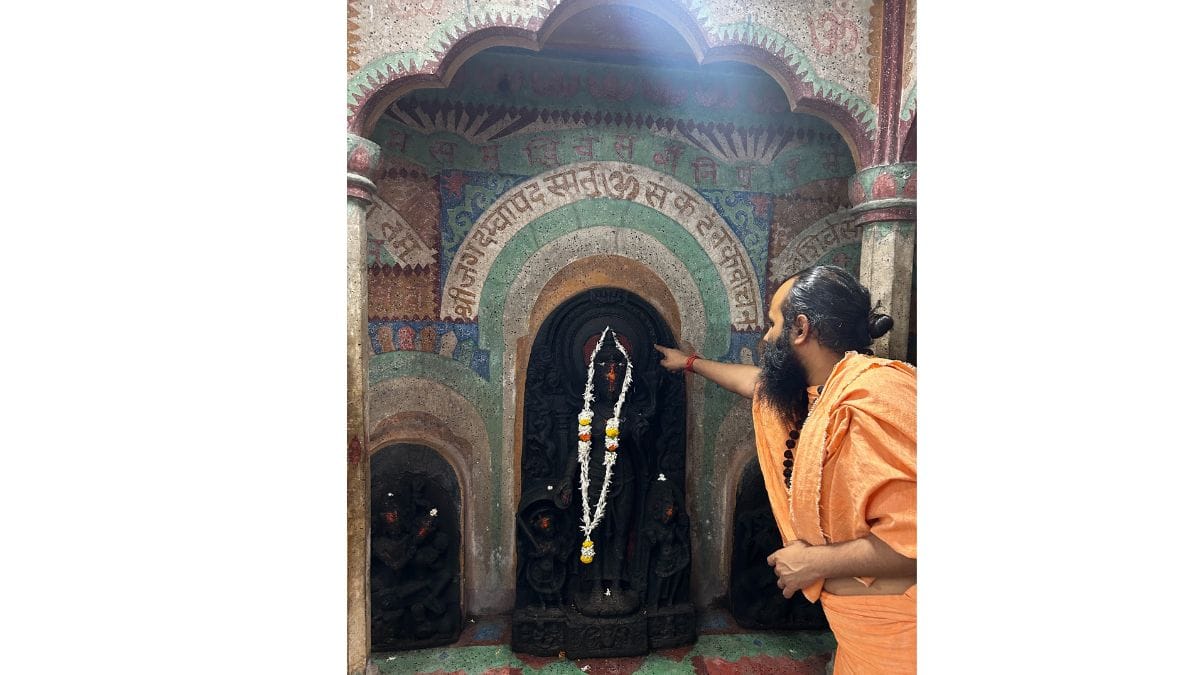

There have been some incidents in recent months where many Buddhist monks have confronted the Hindu priest, a Hindu Math appointee, who looks after the pink coloured three temples, adjacent to the Graph Griha in the Mahabodhi Temple. Videos have surfaced on the internet where the Hindu priest is being asked why Buddha’s idols were adorned in yellow, marked with tilaks on their foreheads, and identified as the Pandavas.

“For the past seven to eight years, the Math has quietly drawn people to the Mahabodhi Temple under the guise of pilgrimage to the Pandavas. Is this not an insult to our faith?” Lama questioned. While he acknowledged that this issue is not the primary concern, he expressed a growing sentiment among Buddhists—that until they gain complete administrative control, the Math’s efforts to ‘Hinduise’ the Buddhist faith will persist.

Swami Vivekanand, 38, the acting Mahant of Bodh Gaya Hindu Math, and a successor in the lineage of the 19th founder of the Math, Mahant Ghamandi Giri, alleged that the ongoing protests are being fuelled by external forces trying to disrupt communal harmony—particularly in the wake of the successful Maha Kumbh, where Hindus demonstrated their unwavering faith.

“It is out of our large-heartedness that the Buddhists have been able to use Jagannath Temple’s land to create an entrance for the Mahabodhi Temple. We have also ensured representation—four of their members in the eight-member committee,” he stated that the Hindu side is confident that the law is on their side.

“There is no constitutional remedy for their grievances, as we hold legal title over the temple.”

“Even the temple’s main idol was consecrated by us. It rightfully belongs to us, as we see Lord Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu,” he added, “So what’s the issue if Hindus perceive Lord Buddha’s five idols as the Pandavas, or Maa Tara Devi, or Maa Annapurna?”

At the Domuhan protest site, more than two kilometres away from the temple, Buddhists now await the crucial Supreme Court hearing set for 16 May, on which the weight of the movement heavily rests. As of the 2011 census, India has an estimated 8.4 million Buddhist population.

“It’s not a large enough vote bank for political parties to rally behind us,” Lama remarked, referencing the recently passed Waqf Bill and the Supreme Court’s decision to stay it, fully aware of the sensitivities surrounding the issue.

Then, with a tone of frustration and after a deep breath, he posed a question— “In what part of the world is a community denied full control over its holiest shrines? Except us?”

Also read: Rise and fall of Indian Buddhism was a stranger, more exciting process than we know

The ongoing Buddhist protest

Each day, nearly 400 people from across India make their way to Bodh Gaya from Patna—some packed into buses, others crammed into auto-rickshaws or rented tempos. They come with a singular purpose to protest. While some stay for a week, others who can afford it remain longer.

At the protest site, banners of BR Ambedkar and Jyotirao Phule flutter in the wind, welcoming monks in saffron robes. Under tents, women of all ages gather together.

One by one, the protestors rise from their seats to give speeches, demanding full control of the Mahabodhi Temple for the Buddhist community and the repeal of the Bodh Gaya Temple Act.

Decades ago, at just 14, Nirmal Kumar Baudh stood among the demonstrators during the 1992 protests, his young voice demanding justice. Today, as a 47-year-old, he returns to Gaya—not as a pilgrim, but as a protester—reviving the same demand he made all those years ago.

“This is our constitutional right to raise this demand. Last time, some protestors were included in the committee, which led to a settlement. Had that not happened, we might have succeeded in getting the Act abolished,” he commented.

However, the Bodh Gaya Hindu Math dismissed the protest as not genuine, stating that they share a cordial relationship with both the committee and the monasteries.

“We still host Buddhist monks in our math,” said Swami Vivekanand. “They will soon be removed from the protests—you’ll see.”

The Math is prepared to fight a legal battle, relying on the same journals, archives, and statements to assert its claim to the title. They believe the Places of Worship Act of 1991 will support their cause.

The Bodh Gaya Temple Act

The battle isn’t about religion or land. It’s not even about history. It is over which lens to view the past from.

According to historical records, in 260 BCE, Emperor Ashoka, after newly embracing Buddhism, visited Bodh Gaya and commissioned the construction of a temple at the site where the Buddha had attained enlightenment nearly three centuries earlier. For centuries, the temple remained under Buddhist management. History took a different turn in the 13th century. Bakhtiyar Khilji’s invasion disrupted Buddhist control, and over time, the temple remained largely abandoned.

Mahabodhi Temple’s official website says that in 1590, Hindu monk Ghamandi Giri arrived at the temple, settled there, and established the Bodh Gaya Math. His descendants took over the temple’s affairs, keeping it under the Hindu Mahant’s control for nearly 300 years.

“He took care of the temple during a crucial period—so how can they claim that Hindus have no stake in it?” Swami Vivekanand questioned. Lama countered, alleging that the Math had begun worshipping Buddha through Vedic rituals, straying from traditional Buddhist practices.

Prof. KTS Sarao, Department of Buddhist Studies, University of Delhi, said that Indic Dharma religions have long shared sacred sites, deities, and ideas.

“The Mahabodhi Temple and its revered peepal tree reflect this tradition, with the tree being worshipped even before the Buddha. According to Xuanzang, Brahmins built the temple, the Buddha image, and the nearby tank,” he added.

However, UNESCO recognises that between the 13th and 18th centuries, the temple lay in disrepair until the British initiated restoration efforts.

Buddhist monks visiting from Sri Lanka and Japan in the late 19th century tried to reclaim their heritage. Forming the Mahabodhi Society, they began a movement to restore Buddhist authority over the temple.

Following India’s Independence, the Bihar government attempted to resolve the dispute by enacting the Bodh Gaya Temple Act in 1949, formally transferring the temple’s management from the Bodh Gaya Math’s Hindu leadership to an eight-member committee composed of four Hindus and four Buddhists. The District Magistrate (DM) of Gaya became the ex-officio chairperson of the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee (BTMC). For decades, this arrangement continued—until Buddhist voices once again rose in demand for autonomy.

In 2012, two monks, Bhante Arya Nagarjuna Shurai Sasai and Gajendra Mahanand, filed petitions in the Supreme Court, challenging the Bihar government’s temple act. Their petition remains unheard to date.

Meanwhile, the All India Buddhist Forum (AIBF) has now stepped in, filing an intervention petition to push for an urgent hearing.

“This time we are hoping for something from the court,” Lama said the petition is filed in his name.

Amid protests and petitions, a new vision for the Mahabodhi Temple is also underway. In the Union Budget 2024-25, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced plans to transform the temple corridor into a world-class pilgrimage site, modeled after the celebrated Kashi Vishwanath temple corridor in Varanasi.

As the temple’s transformation unfolds, questions from various groups intensify about governance—who will oversee these changes, and how will the existing power structure adapt?

As of now, the BTMC remains incomplete, with only six members instead of eight, leaving two posts vacant. Buddhists have held resentment over what they believe is the Brahmins’ monopoly on the temple’s affairs. This feeling has led to tensions over who gets to make decisions. In response, the Hindu side points to the current composition of the committee, arguing that they are actually in the minority within the present structure.

“There are only two Hindu members in the committee; it’s we who are in the minority,” Swami Vivekanand responded, dismissing allegations of Brahmin dominance. “In fact, the current Mahant Triveni Giri (since 2022) isn’t a Brahmin, and neither am I.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Nice. After reading this, I am in Support of Hindus. Buddha is also a Hindu god.

Dividers in chief: Khilji, Nehru

The divided: Hindus and Buddhists, both Dharmics who have historically stood together.

ab bolo batenge to … ?