Trichy: The deadline to repay the loans he had taken out for his daughter’s wedding 10 years ago was weighing heavily on farmer Rajagopal. So, he decided to sell the 1.2 acres of land that he owned in Thiruchendurai village and close the loan.

But when the 70-year-old arrived at the sub-registrar’s office in Trichy, he got a shock. He was told that the land he had owned for 20 years wasn’t his after all. That records said his plot—along with much of the village—belonged to the Tamil Nadu Waqf Board. If he wanted to proceed, he’d need a No Objection Certificate from them.

That was 2022.

Soon after Rajagopal’s predicament came to light, the Tiruchirappalli district collector stepped in and ruled that Rajagopal and others could register their land without needing an NOC from the Waqf Board. The matter was solved. Last year, Rajagopal died. But the case lives on, with the BJP making it an example to push the Waqf (Amendment) Bill in Parliament. It’s become the stuff of folklore of Hindutva politics.

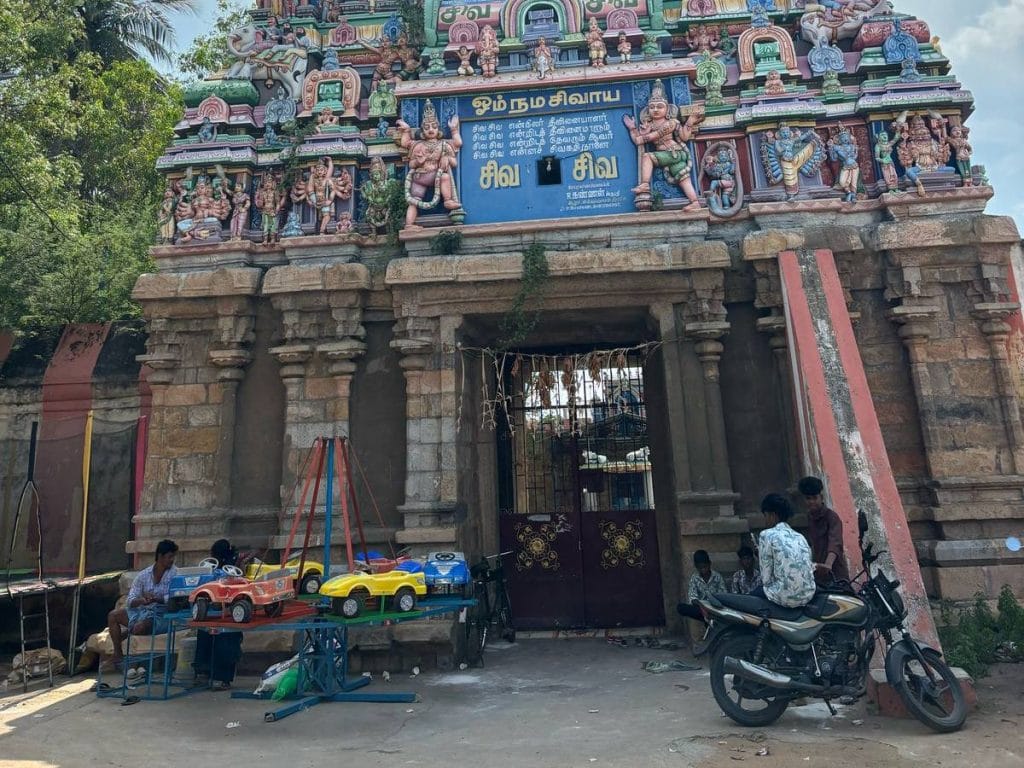

Last week, Home Minister Amit Shah told the Lok Sabha that “400 acres of land belonging to the 1,500-year-old Thiruchendurai temple were declared as Waqf property”. Minority Affairs Minister Kiren Rijiju also claimed the Waqf Board had staked claim to 389 acres in the village, including a 1,500-year-old Shiva temple—Manendiyavalli Sametha Chandrasekhara Swamy Temple, also known as Sundareswarar Temple.

In my entire life, I have never seen Muslims in our Agraharam or even heard that they lived here. Then how can a village and temple older than the Muslim invasion become Waqf property?

-Bala Subramanian, resident of Agraharam in Thiruchendurai

With the political rhetoric, old fears have been revived in Thiruchendurai. Especially in the Agraharam, or Brahmin quarter, where around 45 families are spooked that the land beneath their homes could suddenly turn out to be Waqf property. No one’s really sure what’s what.

“It was only Rajagopal who confirmed it officially and upon checking, we learnt that several acres of land in this village is under Waqf Board. But we did not check individually,” said 85-year-old Bala Subramanian. Things may have worked out in Rajagopal’s case, but there’s always been a sliver of uncertainty ever since.

While the residents are reassured by the new Waqf Act coming into effect, they aren’t entirely sure what protections it can give them.

“I’m sure that the BJP’s Waqf Act will save our property—but I don’t know the exact details,” said resident V Kannan, a retired government employee.

Waqf officials, however, dismiss the fears around the land and say that the ongoing controversy has been manufactured for political gains.

“The issue was sorted long before,” said Tamil Nadu Waqf board president K Navaskani. “The BJP is trying to gain political mileage out of it.”

Even after Rajagopal’s case was solved, the Brahmin residents didn’t want to take any chances. They reached out to BJP national secretary H Raja.

Also Read: Amit Shah’s support to Kerala village Waqf protest is shaking up state politics

Temples on Waqf land

In Suriyur village, about 38 km from Thiruchendurai, a 1,000-year-old Perumal temple draws around 1,000 visitors every day. What many don’t know is that it stands on land that belongs to the Waqf Board.

And it’s not the only one. Several temples sit on Waqf land in this area.

Revenue officials told ThePrint that these properties were donated to Muslim beneficiaries in the 18th century by Rani Mangammal, a queen of the Madurai Nayak dynasty. According to records, she handed over this land on the condition that existing temples must remain untouched. In 1964, these properties were transferred to the Waqf Board.

“It is confirmed through the revenue records. All these places are referred to as ‘Inam Gramam’, given for free,” said a revenue official, requesting anonymity.

Former Waqf Board president Abdul Rahman said the controversy was based on a misreading of such records. Only parts of Thiruchendurai, he said, fall under the board’s purview, contrary to what Union ministers claimed in Parliament.

“It was a donated land and there is nothing wrong in having a temple in the Waqf property,” he said. “Because the donors wanted the temple to remain as it is. It is not just in Thiruchendurai village—there are several villages where temples are in Waqf property.”

In a state ruled by the DMK—a party long identified with non-Brahmin assertion—Brahmins in Thiruchendurai aren’t sure their concerns will find much resonance. The DMK, notably, has opposed the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025.

Waqf zone, no Muslims

On a Monday afternoon post Panguni Astami, TR Bala Subramanian rinsed his hands on the street after eating prasadham from the Perumal temple nearby. Then settling down in the shaded veranda of his house, he spoke with conviction about the “historic” Waqf law that had saved the properties of Hindus from the Muslims.

In his 80s, Subramanian has lived in Thiruchendurai his entire life and was shocked when he heard that his property might be in danger of a Waqf takeover.

“In my entire life, I have never seen Muslims in our Agraharam or even heard that they lived here,” Subramanian said. “Then how can a village and temple older than the Muslim invasion become Waqf property?”

Subramanian retired as a chemistry teacher in 2000 and his wife was the headmistress of the primary school. His family has lived here for at least six generations.

“All our relatives are in the same village and now since it is the Panguni Astami time, everybody is here and nobody is aware of the presence of Muslims in the region,” he said. As he spoke, he pointed toward a woman walking by, saying she could confirm it too.

It’s not just the Waqf Board that has the property details. Even the government has the records to confirm that all these properties were donated to the board

-Tamil Nadu Waqf Board functionary

Another retiree, V. Kannan, is equally sceptical.

A former LIC employee, he moved to Thiruchendurai in 2000 since he had relatives here and wanted a quiet place to retire. He did not face any problems while purchasing or registering the property. But after the 2022 controversy came to light, he started having doubts.

“I don’t know from where this Waqf board came in between,” Kannan said. “But it has come as a great relief to us that nobody can claim our land just like that, as they did around two years ago.”

Although Bala and Kannan are not aware of the details of the recently passed Waqf (Amendment) Bill, both are confident that it will protect the interests of Hindus.

“I really don’t know what is in the bill,” Kannan said. “But I am sure that it would keep a check on the Muslim and the Waqf board so they cannot make any sweeping claims of our hard-earned properties.”

It’s not just Bala and Kannan. Most of the 45 families in the Agraharam hold the same opinion.

Caste angle

Many Brahmin families in Thiruchendurai thank their lucky stars that the first known victim of the Waqf confusion—Rajagopal—didn’t belong to their community.

“The problem was solved immediately only because the first victim Rajagopal was a non-Brahmin. Had it been us, no one would have cared,” said Kannan. “Now you know the importance of the vote bank.”

Had Rajagopal not been from the OBC community, the district collector may not have been so quick to act in his favour, Brahmin residents allege.

“It was a blessing in disguise that a non-Brahmin farmer flagged the issue for us,” added Kannan. “If not for that one non-Brahmin farmer, all the Brahmins here might have lost our land.”

In a state ruled by the DMK—a party long identified with non-Brahmin assertion—Brahmins in Thiruchendurai aren’t sure their concerns will find much resonance. The DMK, notably, has opposed the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025.

Venkateshwar, a third-generation resident, said the OBCs’ numerical and financial strength far surpassed that of the Brahmins.

“We are all poor. Even across the state we are just 3 per cent, and nobody would have heard our cry. Only because it was an OBC problem, it was sorted and heard,” he claimed.

Also Read: As SC agrees to hear pleas challenging Waqf Act’s validity, clamour grows for a repeal

BJP to Brahmins’ rescue

Even after Rajagopal’s case was solved, the Brahmin residents didn’t want to take any chances. They reached out to BJP national secretary H Raja, who visited the village in 2022, and then again in April 2025, just after the Waqf Amendment Bill was passed in Parliament.

“Had it not been for H Raja ji, it wouldn’t have reached Amit Shah ji’s ears. Our properties might not have been saved,” said Bala Subramanian. “Only the BJP heard the voice of Brahmins.”

No other political party, he added, seemed particularly moved. “It was through a BJP functionary in the village, our problem got national attention.”

We are not even aware of (Waqf issue). There’s no need for us to sell our property, and we’re not prosperous enough to buy land here either

-S Perumal, a non-Brahmin resident

Outside the Agraharam, however, the non-Brahmin Hindus and Muslims were largely unaware about the property controversy and the new Waqf law.

By residents’ count, the village has 45 Brahmin families in the Agraharam, and roughly 45 non-Brahmin families, 20 Dalit families, and 20 Muslim families elsewhere.

S Perumal, a non-Brahmin resident, shrugged off the entire controversy.

“We are not even aware of it. There’s no need for us to sell our property, and we’re not prosperous enough to buy land here either,” he said. “Even the old man Rajagopal wouldn’t have had to sell his land if he’d married off his daughters at a young age.”

There’s no history of communal tension here. Muslim and OBC families live side by side near the small village mosque.

“You can see it for yourself, the mosque is just 100 metres away from here. They do their prayers and we do our prayers during our festive times. This is how we have been,” said resident C Chandrakumar.

Similarly, 55-year-old Meeran, who lives near the mosque and runs a meat shop in the locality, said he had never had any dispute with the people around.

“As far as I know, I am the second generation and my two sons are third generation living in this village. We never faced any discrimination or dispute with the Hindus here,” he said.

He said he was unaware of the developments in the dispute, but claimed that the property he lives on—and the land on which the mosque stands—belongs to him.

“It’s me who gave the land to build a mosque. As long as it is maintained by the Waqf Board, it is fine. But if they are making somebody else maintain it, I would ask them to return it to me,” Meeran said.

A functionary of the mosque, who did not want to be named, said a vast majority of the property in the village was donated land.

“It’s not just the Waqf Board that has the property details. Even the government has the records to confirm that all these properties were donated to the board,” the functionary said. “The only dispute is whether it was donated by Rani Mangammal or the former prince of Arcot.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

BAN WAQF.

is this fact check,,clearly it wasnt under wafq and it was just issue caused by digitizing hard copies…. full journalism without scoping out the basic details….smh

All land belongs to Hindus.The land given by Arcot or Ranimangal were correct during that time.They did for their own safety or survival.Think of present state of affairs and the problem has to solved. We are living in Arab world or Afghanistan or Pakistan. With thinking of minority votes Politicians should think as Indian and solve this problem.

All waqf is a scam. Wonder who have the authority for this land to be gifted.