Mumbai: There have only been two Bollywood blockbusters in 2025. And it is already March. There were just six in all of 2024. People flocked to Dil Toh Pagal Hai on Valentine’s Day and cheered for Sanam Teri Kasam and Yeh Jawani Hai Deewani, dancing inside cinema halls and posting Reels. This is the stuff of a thriving movie culture.

Except it’s not.

India’s love for cinema is being sustained by the lure of old hits. It’s been three years since the pandemic ended. But Bollywood is still suffering from long Covid. Everybody is still blaming the mess on Covid.

A Bollywood obit may be premature. But the writing on the billboards is crystal clear. Denial is no longer an option.

“The industry is coming out of a delusion,” said Siddharth Jain, a producer and founder of The Story Ink, a book-to-screen adaptation company that holds the screen rights to more than 500 books. “The business cycle is resetting. Everyone is taking fewer risks. I feel that it is better to be slow, recalibrate, and come out stronger.”

Now producers and distributors are holding their breath for a morning-after reinvention. Industry insiders say 2025 is the year to watch for this new, new Bollywood. Sanjeev Kumar Bijli, executive director of PVR Inox, says that 2025 and 2026 will be the years when the industry finally comes back to “normal”.

What industry leaders are still scrambling to figure out is what this ‘normal’ is going to look like. The old script—stars, spectacle, and a festival release—is no longer guaranteed to work. The new normal of Bollywood will perhaps be one without a larger-than-life star culture and bloated budgets—among the main culprits in the industry’s slide.

The audience has gotten very selective about what they want to spend their time and money on going to the theatre. South Indian films are finding an audience in Hindi markets. But, the vice versa is not true

-Karan Taurani, VP & media analyst, Elara Capital

Even before Covid emptied theatres, the warning signs were flashing on phone screens.

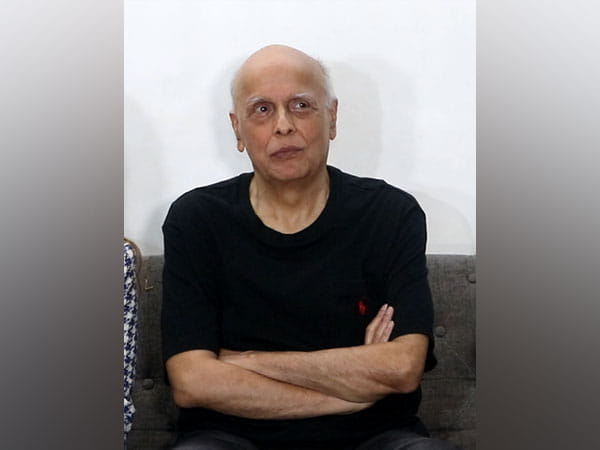

Mahesh Bhatt, director of the evergreen films Aashiqui and Dil Hai Ke Manta Nahin, recalled a meeting with Apple CEO Tim Cook back in 2016, when the latter was visiting Mehboob Studios in Mumbai.

“He asked me how cinema had changed over the years, the way it’s consumed and distributed,” Bhatt said. “I told him it had changed completely. Then he picked up the smartphone from my hand and held it up, saying, ‘All you need is this to consume and distribute.’”

And then when people were stuck inside during lockdowns and theatres shut, streaming exploded and production houses pulled the brakes on big-ticket releases. The star system, already on the track to burnout, became harder to sustain.

“We’ve seen a shift in consumer behaviour,” said Bijli. “Admissions are lower, fewer people are coming to cinemas, and other forms of entertainment seem to be growing: pickleball, paddle, live concerts, performances. But we believe very strongly that this is a temporary change in habit.”

Bijli is still betting on the stars to deliver. He listed big releases slated for 2025, all headlined by top names—Sikandar with Salman Khan, Jaat starring Sunny Deol, Housefull 5 with Akshay Kumar and Sanjay Dutt, War 2 with Hrithik Roshan and Kiara Advani, Aamir Khan’s Sitare Zameen Par, and Alpha featuring Alia Bhatt.

While this full slate may be able to carry the industry on its shoulders in 2025, it’s only temporarily masking what has essentially changed about Bollywood—to its detriment.

Once upon a time, big-ticket films fought for the same Friday release—Om Shanti Om and Saawariya in 2007, Dilwale and Bajirao Mastani in 2015. Now, there are stretches when nothing releases at all.

Also Read: Telugu films were most successful in 2024. No wonder Anurag Kashyap wants to ditch Bollywood

Gaping cracks behind the gloss

On paper, the Hindi film industry doesn’t look too bad.

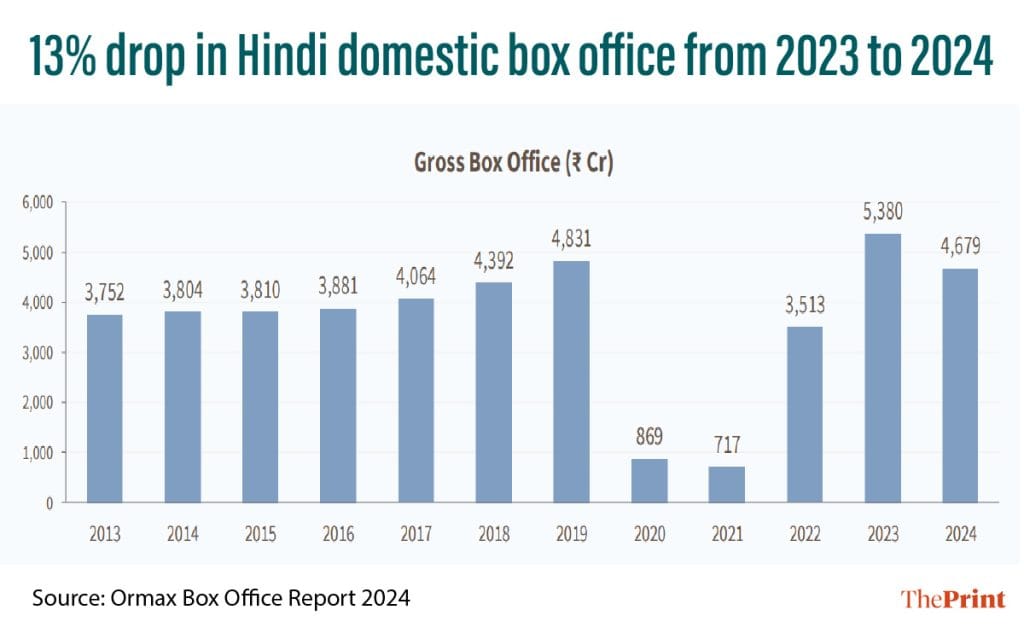

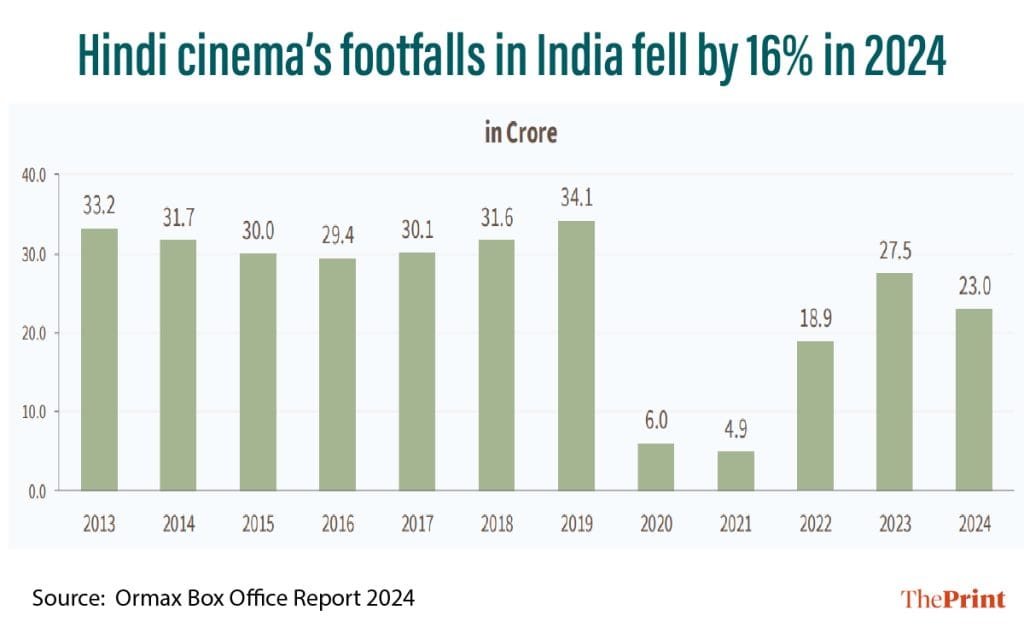

The Ormax Box Office report for 2024 pegs the Hindi film industry’s earnings at Rs 4,679 crore. In 2023—a year with blockbusters like Jawan, Pathaan and Dunki—it was Rs 5,380 crore. Even the pre-pandemic benchmark of 2019 was Rs 4,831 crore.

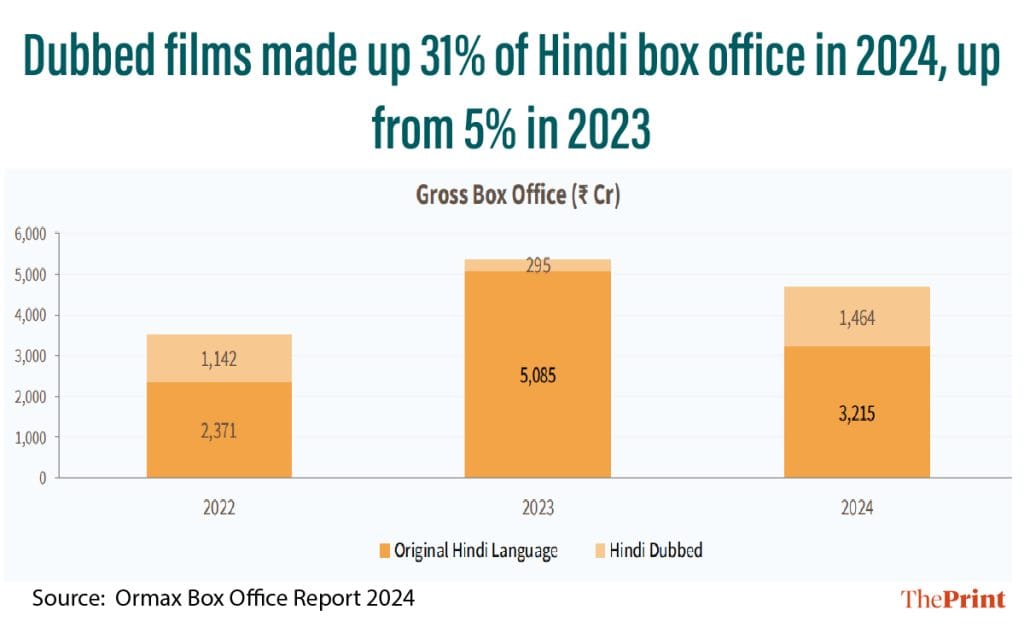

But strip away the gloss, and what’s left is an industry running on fumes. Over a third of the revenue in 2024 came from dubbed titles, mostly Pushpa 2 and Kalki 2898 AD. This means that the earnings from original Hindi films was a modest Rs 3,215 crore, of which about 30 per cent came from just two titles—Stree 2 and Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3.

The industry is relying disproportionately on a few movies to do all the heavy lifting. Big films are getting bigger and the smaller ones are mostly bombing. Cinema theatres are now competing not just with OTT but with an ever-growing platter of leisure experiences, from concerts and outdoor dining to sports events.

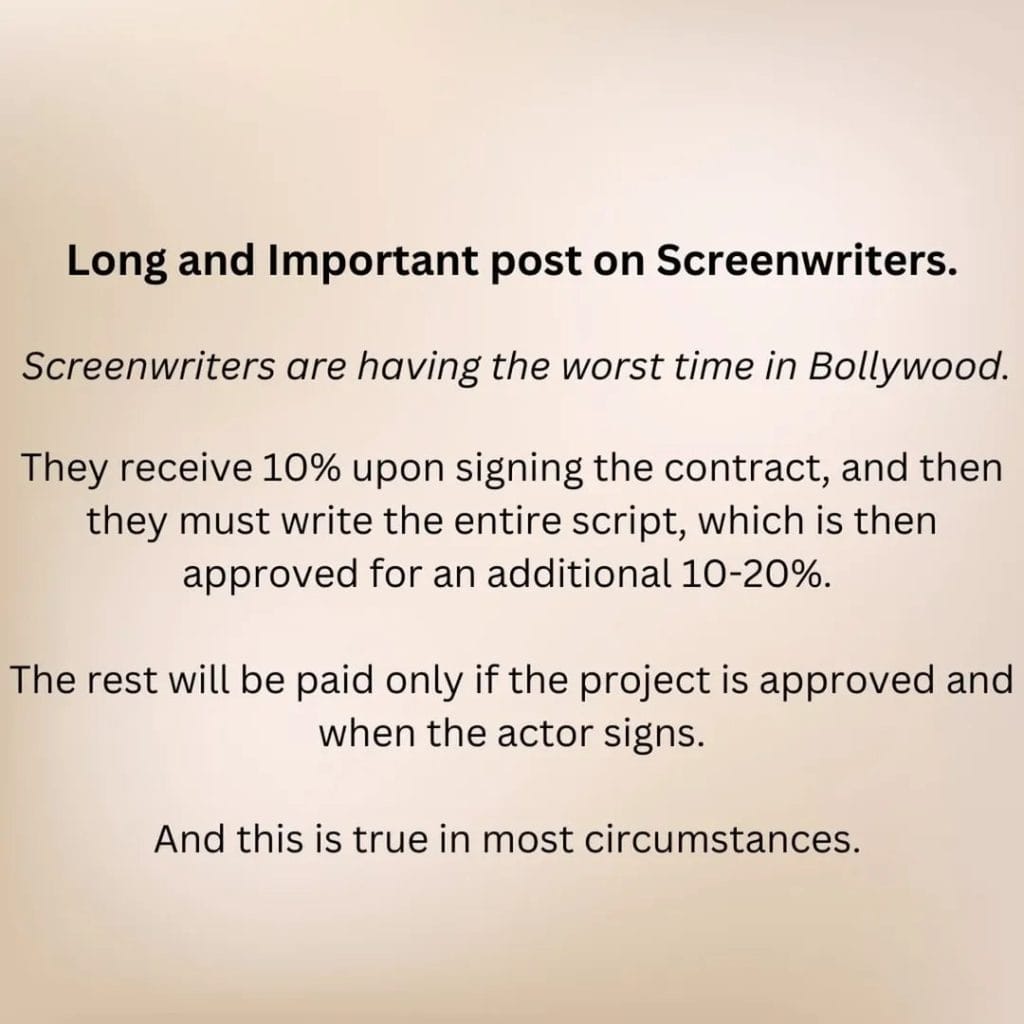

Screenwriters, meanwhile, are bearing the brunt of the slowdown. Last month, Darab Farooqui, the screenwriter behind films such as Dedh Ishqiya, Notebook, Tigers and Ae Watan Mere Watan, put up a long note on Instagram about how difficult it’s become to work with Bollywood producers.

Writers, he said, get just 10 per cent of the total contract amount on signing. Then they write the entire script. If it’s approved, they get another 10–20 per cent. The rest is only paid if—and when—the project is greenlit and an actor comes on board.

This “exploitation,” his post added, has become almost a norm post the pandemic.

Producers are no longer sure what works on the big screen. Actors won’t budge on fees. Streaming platforms aren’t buying the way they used to, with their focus having shifted to profitability over fresh content. As a result, very few films are being greenlit, exacerbating the hardships of writers like Farooqui.

“Producers gain huge leverage here. For the cost of one script they may invest in three or four projects, reducing their risks significantly and shifting the risk entirely to writers. Although the writers incur all of the risks, the profits go entirely to the producers and actors…But, there is no correction here and nobody is listening,” Farooqui’s post said. “This is why we make lousy movies; because writers suffer.”

Audiences, too, are tuning out. Many say they no longer want to pay for theatre tickets because the scripts are poor.

It wasn’t always this way.

Veteran filmmaker Subhash Ghai, known for films such as Ram Lakhan, Khalnayak and Taal, said there was a time when the writer was among the most important people on a film. He would consult writers even on casting choices.

“I have always told my writers to take a rupee more than what you would have charged in the market, but we want to work towards a good film. We would not even start the discussion with money or payment patterns,” Ghai added.

“Of course, if someone was in urgent need of money, I wouldn’t blink to pay them all at one go. Such was our relationship. There was mutual trust. That’s not there anymore.”

100-crore club & vanishing mid-budget films

Back in the 1980s, Disco Dancer, starring Mithun Chakraborty, became the first Indian film to cross Rs 100 crore, a lion’s share of which came from overseas earnings. But the term “Rs 100-crore club” didn’t even exist then.

In a 2013 interview with Bollywood Hungama marking 41 years of Disco Dancer, Chakraborty recalled how stunned he’d been. “Itna paisa, baap re baap” (So much money, my god), he had said.

By then, the 100-crore club had become the gold standard for films.

According to IMDb, between 2008, when Ghajini joined Disco Dancer in crossing the Rs 100-crore mark, and 2020, before theatres shut during the pandemic, 91 films entered the club. Of these, all but two—the Baahubali films—were in Hindi. Eight Hindi-language films even crossed the Rs 300 crore mark in that period.

Since then, the 100-crore club has only grown more top-heavy.

Post-pandemic, from November 2021 to 2025 February, 34 films became a part of the Rs 100-crore club, with six being non-Hindi. The stark difference between this pre- and post-pandemic period is that just in 26 months, between 2023 and 2025 January, six Hindi-language films grossed over Rs 300 crore.

“Earlier, before the pandemic, the top 10 Hindi films would be contributing about 50 per cent of the industry’s revenue. Now they are contributing 70 per cent in the Hindi segment,” said Shailesh Kapoor, founder and CEO of Ormax Media.

One reason for this is that mid-budget films are slowly becoming an endangered species.

“The long tail of the smaller midrange films, like the Ayushmann Khurana-type movies earlier, used to do quite well at about Rs 70 crore to Rs 100 crore. They used to provide that additional cushion, week on week. Now those films are not working for theatrical releases,” Kapoor added.

For instance, Loveyapa, featuring Junaid Khan and Khushi Kapoor, earned just Rs 9.56 crore worldwide since it’s 7 February release this year. It was reportedly made on a budget of Rs 60 crore.

“Mid-range genres, where film-making was thriving and experimentation was possible, are being pushed aside,” said Pranjal Khandhdiya, producer of Piku, Super 30 and 83.

Before the pandemic, the top 10 Hindi films would be contributing about 50 per cent of the industry’s revenue. Now they are contributing 70 per cent in the Hindi segment

-Shailesh Kapoor, founder and CEO, Ormax Media

The same story is playing out in the South. Superhits like Pushpa, KGF, and Kalki 2898 AD have not just left Bollywood in the dust but also the smaller budget sections of regional industries.

“Even in regional cinema, it is the big films that are getting bigger while mid-range films are not doing well,” said Karan Taurani, senior vice president and media analyst at brokerage firm Elara Capital. “The audience has gotten very selective about what they want to spend their time and money on going to the theatre. South Indian films are finding an audience in Hindi markets. But, the vice versa is not true.”

Taurani estimates that over the next few years, 10 to 15 large-budget films will drive 80–90 per cent of Hindi box office revenue.

Once upon a time, big-ticket films fought for the same Friday release—Om Shanti Om and Saawariya in 2007, Dilwale and Bajirao Mastani in 2015. Now, there are stretches when nothing releases at all.

Kapoor said there used to be 60–70 well-marketed Hindi films hitting theatres each year before the pandemic. That number has now dropped to 30–35, with large gaps between releases and dismal theatre occupancy.

A scramble to fill empty theatres

With theatres half-empty for long stretches, exhibitors are trying anything and everything to keep the seats warm, from screening cricket matches to concerts.

“We have got 1,750 screens across the country. Currently we are operating at an occupancy of 30 per cent or lower,” said Bijli of PVR Inox. “So we are programming alternative content, which can be cricket matches, football matches, re-releases of Hindi movies, the Oscar film festival. We did the BTS concert, Taylor Swift concert. The infrastructure is there, so why not use it to bring in more people?”

Last month, PVR Inox even tied up with Isha Foundation to livestream Mahashivratri celebrations on select screens across the country for Shiva devotees.

The company kicked off its re-release experiment with Rockstar last year, and kept going with Tumbbad, Yeh Jawani Hai Deewani, Sanam Teri Kasam, Silsila, Jab We Met, Interstellar, and others. Some of these films have done far better on their return run than new releases. Yeh Jawani Hai Deewani made over Rs 10 crore in re-release; Sanam Teri Kasam touched Rs 50 crore.

In its latest earnings call last month, the management of PVR Inox said that re-releases and other events accounted for 4.3 percent of admissions since April. It’s a small number but better than 0.

PVR Inox also has ‘Cinema Lovers Day’, where tickets for new releases are sold at a highly discounted Rs 99. Smaller films like Crazxy, produced by Tumbbad’s Sohum Shah, have also tried Buy 1 Get 1 Free offers to tempt audiences.

“Some things are working, some things are not,” Bijli said. “But we have to keep trying.”

What gets made—or shelved—now hinges on what Ormax’s Kapoor calls “theatrical worthiness.” Flashy blockbusters are seen as the only viable way to recover costs.

Chase for ‘theatrical worthiness’

Most millennials remember going to worn-out single-screen cinemas with rickety seats and cheap salted popcorn in polythene packets. That era is nearly extinct.

Multiplexes began pushing single screens out in the early 2000s. The 28 percent GST on movie tickets further hit the single screen business hard, and the pandemic was practically a death knell. Along with them went a large chunk of the audience—especially with multiplex tickets rarely costing under Rs 500, and a popcorn-coke combo priced about the same.

Ghai said that about 70 per cent of Bollywood’s audience vanished along with the single screens.

The digital era rewards what is most engaging and not what is most meaningful. In a landscape where, virality has replaced artistic merit, spectacle outweighs substance

-Mahesh Bhatt, filmmaker

“It killed the mass audience. What we need is basic comfortable seats and a limited ticket price of Rs 99,” said the filmmaker, whose chain Mukta A2 Cinemas has tried to do just that with 24 properties and 63 screens.

It’s perhaps fitting that even at contemporary prices, nostalgia still sells, sometimes more than new releases.

When PVR Inox re-released Yeh Jawani Hai Deewani, the response was overwhelming. Theatres were full of Gen Zs who hadn’t seen the film during its original 2013 run or were too young to remember it. Bijli recalled how some rushed to the front of the screen and danced to every groovy song, from Balam Pichkari to Badtameez Dil.

“These were college-going students so they probably hadn’t seen the film on the screen, and they just knew the music,” he said. But every nostalgic classic doesn’t click.

“Kal Ho Na Ho didn’t do well, and neither did Karan Arjun. I don’t know why because they had fab music. We have to keep trying,” Bijli added.

That uncertainty extends to new releases too. And when in doubt, the most bankable bet is often a big-budget extravaganza.

“The digital era rewards what is most engaging and not what is most meaningful. In a landscape where, virality has replaced artistic merit, spectacle outweighs substance,” filmmaker Bhatt said.

What gets made—or shelved—now hinges on what Ormax’s Shailesh Kapoor calls “theatrical worthiness.” Flashy blockbusters are seen as the only viable way to recover costs.

“Everybody has reached an understanding that the cinema that’s going to work is more spectacle driven,” Kapoor said.

In pursuit of this theatrical worthiness, producers are turning to sequels of hit films, like Bhool Bhulaiyaa or Gadar. Many are also tapping into the predominant political undercurrent of nationalistic pride and muscular religiosity.

Bollywood has churned out a slew of Ramayana-inspired big-hitters in the last couple of years, along with historical stories like Chhaava, based on Maratha warrior king Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj. But even this is no guarantee of theatrical success. Adipurush (2023), with a star cast of Prabhas and Saif Ali Khan, sank without a trace.

Another formula that’s gained traction is ideologically charged films with a clear political bent. It doesn’t always work—as seen in Kangana Ranaut’s latest flop Emergency—but some films have raced ahead at the box office.

The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story, both aggressively pushed by BJP leaders who booked entire theatres and arranged special screenings, did staggering numbers. The Kashmir Files, made at a budget of about Rs 20 crore, collected Rs 341 crore worldwide, while The Kerala Story, created for Rs 15 crore, earned Rs 302 crore.

“Popular culture is not the culture of people, but the culture of power,” Bhatt said. “So, the irreverence that was there, the rebellious spirit, has been replaced by glossy high budget films, serving ideological interests rather than artistic interests. The industry’s major players are also aligning with this political power.”

It’s not much different in Hollywood.

“A filmmaker in the US told me there is a conscious effort to not make anything that displeases the establishment,” Bhatt added.

Where Indian cinema and Hollywood are also converging is tech gimmickry. Producers are now attempting to build VFX-heavy cinematic universes—channelling Marvel, but with a desi spin.

The irreverence that was there, the rebellious spirit, has been replaced by glossy high budget films, serving ideological interests rather than artistic interests. The industry’s major players are also aligning with this political power

Mahesh Bhatt, filmmaker

In 2023, YRF officially unveiled its Spy Universe logo, over a decade after the first instalment, Ek Tha Tiger, released in 2012. The upcoming Alpha, starring Alia Bhatt and Sharvari Wagh, will be the seventh installment of the franchise and the first to be led by women.

Then there’s Maddock Films and its horror-comedy universe, comprising films like Stree, Bhediya, and Munjya. It announced eight more titles this January, including Shakti Shalini and Chamunda. The saga will conclude with Pehla Mahayudh and Dusra Mahayudh, which will hit the theatres in 2028.

But these are expensive genres. Only production houses with a solid bank of film and music rights, diversified revenue streams, and strong relationships with major streaming platforms are able to thrive.

Streaming platforms, which had bought a flood of content during the pandemic, are no longer buying as many films. Their subscriber base has plateaued. Profit is the new priority.

The survival game for studios

Not everyone in Bollywood is struggling. Some of the big players are doing just fine since they’ve figured out how to stay cushioned.

In fiscal 2023, Yash Raj Films doubled its revenue from the previous year, raking in Rs 1,466 crore, largely due to the juggernaut that was Pathaan. A report by Acuite Ratings & Research noted that the next two years may not look as good but would still be “stable. That’s because it has fallbacks such as licensing, music rights, and a full-fledged talent management arm that handles everything from endorsements to appearances for a range of artists, from Sonam Kapoor to Ahaan Pandey.

Dharma Productions, too, has the necessary padding to weather precarious times. The firm’s revenue from its core business—the distribution and exhibition of films—plummeted by 83 per cent from Rs 656.09 crore in 2022-23 to Rs 111.38 crore in 2023-24, per the company’s filings with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs.

But the overalltopline shrank by only 50 per cent. Revenue from other streams—music rights (Rs 82.26 crore), digital rights (Rs 163.29 crore), and ad films (Rs 70.58 crore)—helped absorb the hit.

An industry source well acquainted with the business model of Dharma Productions—founded in 1976 by Yash Johar—explained the math: the studio typically has 65–70 per cent of a film’s cost covered before a single frame is shot.

“They first ensure they have access to the best scripts, and decide if the script is going to fly with various platforms. Then there is the music platform, which they could either own the IP for or sell it to a music label. So, what they are exposed to is only about 30 per cent of the cost of the movie,” the source said.

Smaller production houses, however, don’t have that luxury. Many won’t shoot until their profit-and-loss statement for the film shows at least a modest return. But very few scripts are passing that test now. Streaming platforms, which had bought a flood of content during the pandemic, are no longer buying as many films. Their subscriber base has plateaued. Profit is the new priority.

“They are not getting incremental subscribers, the returns, the commensurate watch time,” said Elara Capital’s Taurani.

OTTs are now more cautious with their spending since content alone isn’t driving growth like it used to. Smaller studios and indie filmmakers are getting squeezed out as OTTs are increasingly backing big production houses who can deliver scale, stars, or brand value

“The large production companies are fine because they are making the big films and have relationships with the large OTT platforms to secure deals before their film takes off. It is the smaller production companies that are struggling,” Taurani added.

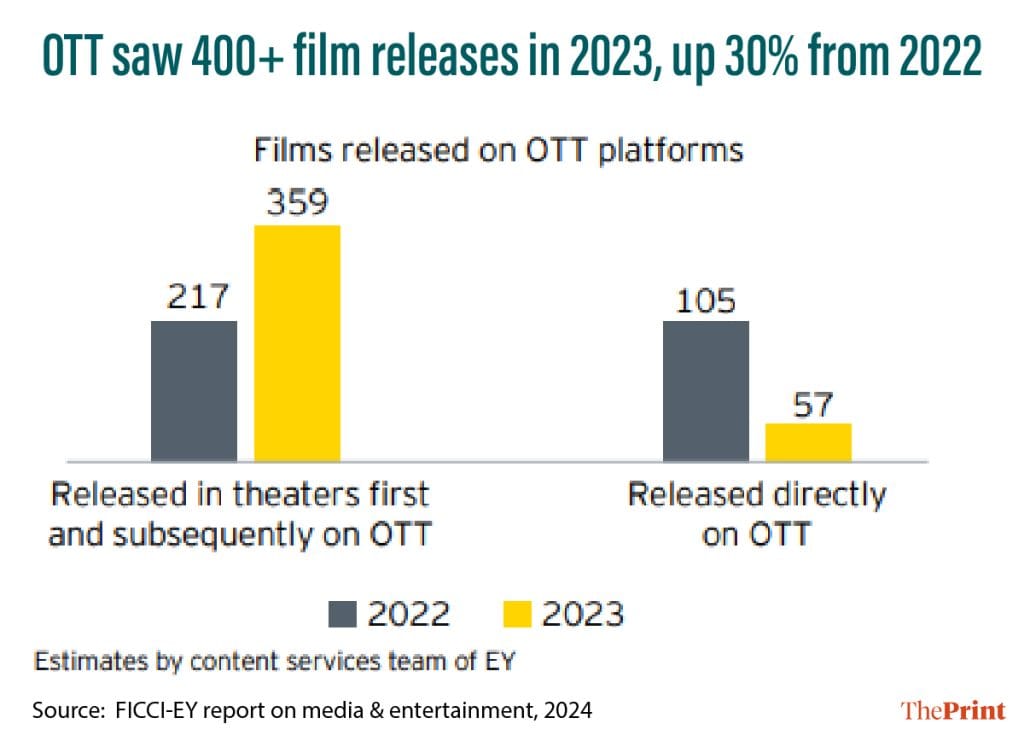

A FICCI-EY report shows that number of films released in theatres first and then streamed rose to 359 in 2023 from 217 in 2022. However, direct-to-digital releases dropped to 57, half of the previous year’s count.

“OTT content volume growth slowed in 2023 due to profitability pressures, and could fall in 2024,” the report said.

A screenwriter who did not wish to be named said there had been almost no work for about six months.

“There were two films I wrote that never got made. Amazon Prime finished its inventory and then did not commission anything new. In between there were mergers—Jio-Hotstar, Voot-Jio— and only now have they released their slate of content, a year after the mergers,” said the writer, who has now taken up a full-time job as a development executive with a music production company to make ends meet.

Meanwhile, bigger production houses have carved out separate OTT wings. Dharma’s Dharmatic Entertainment has Nadaaniyan and Aap Jaisa Koi lined up for Netflix this year. YRF’s streaming arm, YRF Entertainment, has announced Akka and Mandala Murders. Excel Entertainment recently released Dabba Cartel, created by Tiger Baby Films.

Even OTT platforms are feeling the pressure from competition. Some have slashed prices or launched separate free content verticals. In February, Amazon MX Player announced a new slate of releases, distinct from Amazon Prime Video, which itself has exclusive tie-ups with Excel and Dharma. The race for streaming rights now begins before a film is even released.

Star power

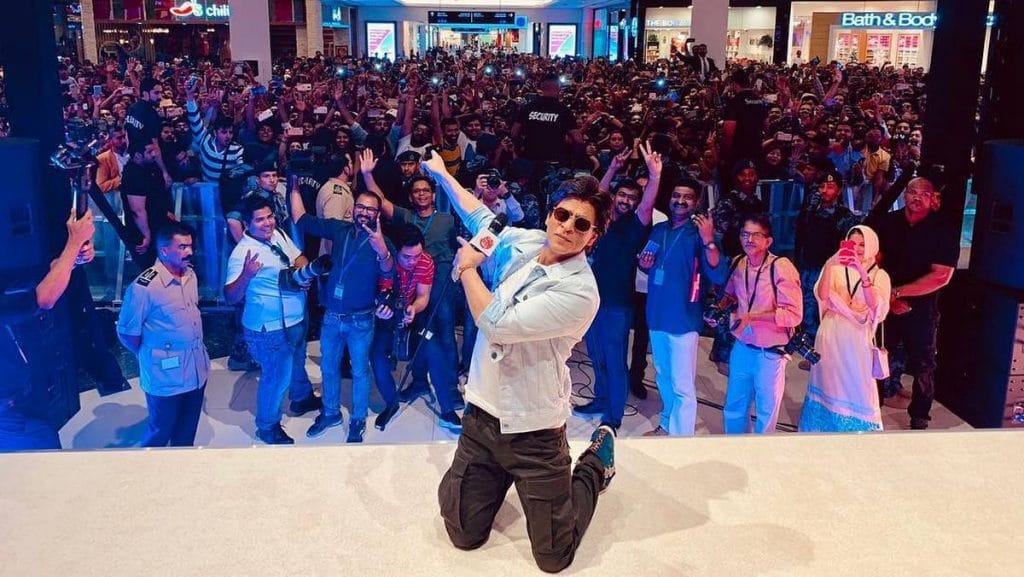

Stars are no longer just stars. A handful of them are the centre of gravity the Hindi film industry still orbits around.

There are about 10 viable actors in Hindi cinema and they all are all asking for sun, moon, and earth,” Dharma’s Karan Johan said in an interview last year. He pointed out the absurdity: actors demanding Rs 35 crore for films that open at Rs 3.5 crore.

Yet, in filmmaker Bhatt’s words, producers still look at stars as “pre-sold tickets”. And exhibitors only want the cinema halls full.

“As long as they have their capacity, or the film maker generates that excitement, whether it is through the support of corporate or political backing, which ensures opening, all is good,” said Bhatt.

Only now, with box office performance no longer assured, people within the industry have started to ask if these are really pre-sold tickets or a burden on budgets.

Filmmakers across the spectrum—from Johar to Ghai to Zoya Akhtar—have lamented about how stars bloat budgets with their hefty fees and huge entourages.

Ghai, who claims none of his 43 films ever crossed their estimated budgets, said filmmakers used to limit actor fees to about 10-15 per cent of total costs. Now, much of a film’s budget is reserved for stars.

There are project makers and there are filmmakers. The project makers say, we will take these stars, present this grand picture for our distributors—it is all chamak-dhamak. But a filmmaker who has conviction in the script doesn’t care about all that

-Subhash Ghai, filmmaker

Where actors are not able to drive budgets beyond a point without cutting their fees, they become co-producers, dipping into a share of the profits.

“For a star, they are looking at each project as a single project. The general problem with the film industry in India is that everybody, whether it is the producer or star, is focusing on the next release rather than looking at the overall health of the industry,” Kapoor from Ormax said.

Stars’ exorbitant fees and delays due to their scheduling issues often significantly expand film budgets. The returns have not necessarily been commensurate.

“There are project makers and there are filmmakers,” Ghai said. “The project makers say, we will take these stars, present this grand picture for our distributors—it is all chamak-dhamak. But a filmmaker who has conviction in the script doesn’t care about all that. Laapataa Ladies is a one example. Can you think of any present-day big star who could have played those roles and still made it a hit?”

One producer, who asked not to be named, also said Bollywood has long prioritised stars over scripts.

“The business of art has become the business of stars. They do deserve fandom, but is that fandom delivering at the box office? Mid-range actors have delivered more commercial success,” he said.

That’s not to say the A-listers never deliver. Shah Rukh Khan’s Pathaan, Jawan, and Dunki and Ranbir Kapoor’s Animal were huge hits. But as Kapoor pointed out, only “three or four” stars can now carry films on their own—Shah Rukh, Ranbir, and, to some extent, Salman and Aamir—“but their peak was a few years ago”.

“Actors like Akshay Kumar, Ajay Devgan, Shahid Kapoor are well known, but don’t have the pull to get audiences to the theatres on their own names. They have to rely on a good trailer, marketing campaign, director, story, music,” he added.

Shahid’s latest film Deva, made for Rs 80 crore, earned just Rs 60 crore worldwide. Ajay Devgn’s Maidaan, budgeted at Rs 200 crore, pulled in barely Rs 51 crore. Akshay Kumar—who Forbes India named in January as one of the country’s ten highest paid actors with a fee of up to Rs 145 crore—also has a patchy track record of late. Among his latest releases, Rohit Shetty’s Singham Again just about broke even.

Some filmmakers are beginning to say it out loud: the future belongs to talent, not stars.

Entourage first

No story captures the fallout of star excess like producer Vashu Bhagnani’s Pooja Entertainment.

Of the four films it released between 2022 and 2024, three flopped. Ganpath earned Rs 18 crore on a reported Rs 150 crore budget. Mission Raniganj made Rs 46 crore against Rs 55 crore. Bade Miyan Chote Miyan, the biggest disaster, earned Rs 72 crore on a Rs 300 crore budget, according to Sacnilk, an industry research and analytics platform. Two of these three—Mission Raniganj and Bade Miyan Chote Miyan—featured Akshay Kumar.

The stars got paid but others didn’t, leading to an outcry from crew members.

Directors Tinu Desai (Mission Raniganj), Ali Abbas Zafar (Bade Miyan Chote Miyan), and Vikas Bahl (Ganpath) all filed complaints with the Federation of Western India Cine Employees (FWICE) over unpaid fees.

“The stars and their entourages were paid first. Otherwise the movies wouldn’t have even been completed,” said Ashoke Pandit, president of the Indian Film & TV Association and chief advisor to FWICE. “But literally everyone else is struggling to get their payments, from technicians to vendors to even the cook on set.”

If the situation isn’t resolved, FWICE may issue a non-cooperation notice. “Which means nobody from the industry will ever work again with the production company,” Pandit said.

He noted that while such large-scale defaults are uncommon, actors and their entourages have always gotten priority.

A production designer who once worked with Pooja Entertainment said she could see the writing on the wall two years ago and got out. She even tried to join a star’s entourage but couldn’t.

“Now I pick up work in other industries— television or even Telugu films,” she said. “These production houses pay the star entourage first, and we come at the very end.”

Also Read: Karan Johar wouldn’t mind ditching the ‘star’ factor

Toward a starless future?

With Gen Z replacing millennials as the dominant moviegoing audience, Bollywood may be heading for a future without a larger-than-life star culture. They simply aren’t so bedazzled by the new crop of actors.

None of the industry’s ‘star kid’ debuts and other ‘fresh faces’ have set the box office on fire.

Azaad (2025), which launched Raveena Tandon’s daughter Rasha Thadani and Ajay Devgn’s nephew Aaman Devgan, sank without a trace. Sky Force, starring Veer Pahariya alongside Akshay Kumar and Sara Ali Khan, earned Rs 134.93 crore over 40 days of its theatrical run, well short of its Rs 160 crore budget. Loveyapa, featuring Junaid Khan and Khushi Kapoor, made more noise for its PR machinery than its script or performances. Even on OTT, star kids have struggled to make a mark. Call Me Bae, led by Ananya Panday, is a rare exception.

“None of the Gen Z stars are that interesting. I liked Vedang Raina in The Archies. Ananya Panday is cool sometimes. But I am not really interested in watching their films for 400 bucks on weekends,” said Sahil Gupta, a law student at Delhi University. “I have Netflix, and my friends share a few other OTT apps, and there’s enough stuff there.”

Some filmmakers are beginning to say it out loud: the future belongs to talent, not stars. On 10 March, director Hansal Mehta posted a list of young male actors on X, calling on the industry to put its “faith” in them, and promising a similar list for directors, writers, and women actors.

“The formula is simple: invest in actors, not ‘stars.’ Write without fear. Direct with conviction,” Mehta wrote.

The rise of universes and franchises may also be nudging Bollywood away from a star-first culture. The appeal of Stree 2, for example, lies as much in the world it builds as its cast, led by Rajkummar Rao and Shraddha Kapoor. Last month, Karan Johar told trade analyst Komal Nahta that he was “inspired” by the success of the film.

“Not like the biggest star of the country is in it. But it is all about the conviction of the producer and the director,” Johar said in the interview.

It was a surprising comment coming from one of the biggest patrons of stardom. Dharma Productions has built its brand on marquee names, from Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol to Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt. But it’s now rethinking the old model, an insider said.

“The ongoing thinking is how do you create the next set of good actors and directors,” the source added. “Karan uses his platform to expose the person to the public, create a certain brand, a certain following and then launch the artist. Once they chance upon an actor and find him or her good, then they would typically sign 3-4 films, so the rates are fixed.”

The times have changed. The audience has changed. The world has changed. But, for the most part, Bollywood hasn’t quite caught up yet.

“The old is not fully dead, and the new is not fully born,” Bhatt said. “We are stuck in that twilight zone.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)