Bhiwadi: Outdoor assemblies are a thing of history, and games are out of the question with the AQI soaring. So the children huddle inside their private school and settle for chess or karate. “Pollution has stolen children’s daily rituals,” says their math teacher Uma Khandelwal. This isn’t Delhi with its infamous winter smog. This is Rajasthan’s Bhiwadi, an industrial township that’s burgeoned into a real-estate hotspot and upmarket retirement hub over the last few years.

Sitting precariously between the Aravallis and Delhi-NCR, it was sold as the best of both worlds. But daily life here means inhaling sheets of dust, acrid smoke rising from factory stacks, and AQI that routinely matches Delhi’s 300-400 range. And yet, nobody wants to talk about Bhiwadi or other towns like it.

The “most polluted city” tag came in 2022, when IQAir’s global data put Bhiwadi among the world’s worst for PM2.5, though the Central Pollution Control Board had said the same back in 2017. It’s a pattern that keeps repeating across India’s industrial towns, whether it’s Byrnihat on the Assam-Meghalaya border or Dharuhera in Haryana — expansion without the necessary infrastructure, civic capacity, buffer zones, or effective pollution-control machinery. It’s a graph where one line keeps rising for growth and the other keeps falling for livability.

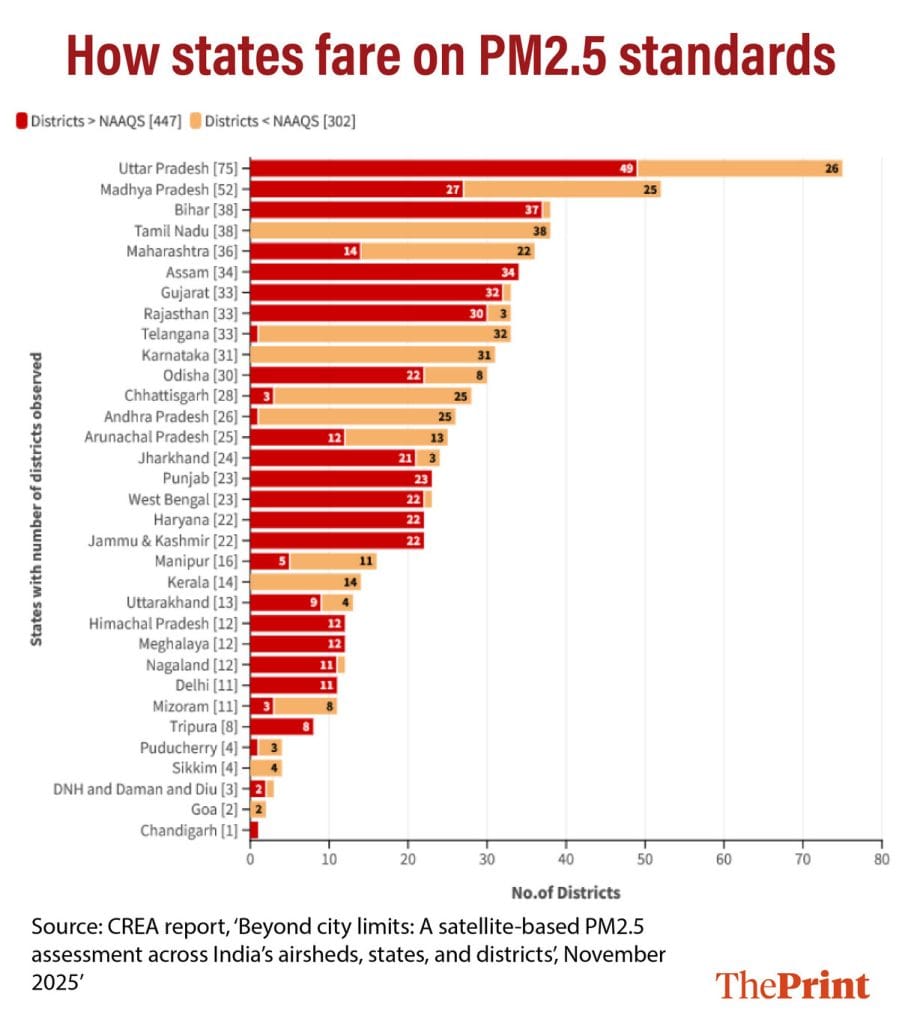

This November, a study by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) found that nearly every region in the country now battles polluted air year-round. It also noted that current data underestimates the crisis in industrial hubs.

“Monitoring stations are often located in cleaner areas, away from industrial zones or busy corridors, which leads to underestimation of actual pollution levels… an industrial hub situated on the outskirts of a compliant district may appear clean because its nearest monitor is placed in a less polluted suburban zone,” the study said. What India needs, it argued, is data that covers not just metros, but small cities and the peri-urban sprawl.

The data exists, the government just doesn’t want to publish it. If a factory near my house is emitting beyond limits, I should be able to see that data live. The technology to monitor industries in real time already exists, but enforcement remains reactive, not preventive

-Debadityo Sinha, lead of climate and ecosystems team, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

Bhiwadi’s rise as an industrial hub began in the 1980s, fuelled by incentives for small-scale units, cheap land, and proximity to Delhi-NCR. Plastic recyclers, metal furnaces, chemical manufacturers, and even global companies such as Honda, Jaquar, and Tata Bluescope Steel all set up shop here. Today the township has around 2,500 factories, most of them MSMEs. The state celebrates this as industrial growth and job creation. But residents tell a story of neglect.

The Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board (RSPCB) conducts inspections, but the ground reality is a stark indictment of enforcement failure. With air quality turning ‘severe’ in November, GRAP-3 kicked in to stop construction, demolition, and polluting vehicles. But Bhiwadi simply kept going. Roadwork carries on in the industrial area; construction continues for a new police control room. Agencies either point fingers at each other or at ‘system’ failures.

“Despite contributing one of the highest GST shares in Rajasthan, Bhiwadi doesn’t have the funds for even routine civic maintenance,” said Satinder Singh Chauhan, chairman of the Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP) in Bhiwadi.

For residents like Deepak Dua, who has lived here for three decades, this gap between authority and action is infuriating. If the pollution board truly has the mandate to act, he asks, why do environmental reports read like obituaries? His two sons, both under four, have chronic breathing issues. He runs Adusuns Medicare, an ayurvedic healthcare MSME that the state points to as a model of industrial growth. Yet, he says he feels suffocated by the contradiction of selling wellness from inside a gas chamber.

From the balcony of his apartment, Dua watches chimneys and warehouses swallow the skyline. He grew up playing cricket on open grounds, but his sons have never known that freedom.

“There isn’t a single park near my house,” he said. “Instead, there’s a massive plant right behind us, and smoke keeps rising from it. I get nervous when my younger one stands on the balcony for too long. I shouldn’t have to worry about my child just breathing the air.”

The city grew on the back of migrant workers and middle-class professionals, but its infrastructure buckled under the pressure long ago. It has drawn people from every corner of the country, yet failed to build the civic basics. Dua says he often looks around and wonders why there are no e-rickshaws, barely any walkable footpaths, why there’s no safe way for a child to cycle.

“These things are not luxuries,” he said. “They are basic urban design. They reduce traffic. They reduce pollution. They give children agency.”

Also Read: A 40-year legal battle for clean air: Why Delhi breathes poison despite steadfast judicial crusade

Paperwork vs pollution control

On most mornings, the regional office of the Rajasthan State Pollution Control Board in Bhiwadi feels less like an environmental watchdog and more like an exhausted outpost. The people holding this system together are inundated.

“We need 50 per cent more staff. With what we have, it’s hard to keep up,” said Amit Juyal, a senior environmental engineer & regional officer, who has been posted in Bhiwadi since January.

His team of 15 people includes six technical officers, six lab staff, one accounts personnel, and two support staff. It’s the only line of defence against thousands of polluting units, not to speak of sifting through overlapping environmental mandates. Handling all the necessary inspections, complaints, and enforcement is nearly impossible.

Before we even step out for an inspection, we’ve already spent half the day on consents and other desk job like answering RTIs, the complaints, compiling different data as per the requirement of HQ, CPCB, CAQM & Ministry

-said environmental engineer Ankur Pathak

“There is no thumb rule for how big a regional office should be,” shrugged Juyal, who has many plants in his office and kept asking his staff to water them appropriately.

For years, the RSPCB struggled on two fronts: it couldn’t meet its own sanctioned strength, and that strength was far too low for Rajasthan’s expanding industrial load. While the state increased sanctioned posts from 600 to 808 in October 2023, officers in Bhiwadi say the allocation on the ground remains woefully inadequate for the scale of the crisis.

A typical day here is consumed not by chasing smoke, but by chasing paper. It begins with consent applications — the legal permits industries need to operate. The Bhiwadi office receives three to four every day, among the highest in Rajasthan. Each file comes with technical drawings, treatment plant designs, emission projections, and compliance histories that have to be scrutinised. Officers have 120 days to clear each application, but with only six technical staff, that deadline has become a formality. Across Rajasthan, there are currently 793 consent applications pending. For Bhiwadi, it’s 90, according to officials.

“Before we even step out for an inspection, we’ve already spent half the day on consents and other desk job like answering RTIs, the complaints, compiling different data as per the requirement of HQ, CPCB, CAQM & Ministry,” said environmental engineer Ankur Pathak, who has also been posted here since January. On top of that, he is also part of the RSPCB’s team that tackles pollution incidents, compliance monitoring, and environmental campaigns such as single-use plastic reduction.

Once the paperwork is reviewed, officers must schedule field verifications and answer industry queries. They face an endless mountain of paperwork: drafting replies to the National Green Tribunal, preparing show-cause notices, issuing directions. Then there are mandatory duties that have nothing to do with regulation, including environmental education sessions, planning events for occasions such as World Environment Day, and responding to frequent administrative reviews from Jaipur.

Over the years, the number of environmental laws they must enforce has grown from a handful to 11 major Acts, but their staffing hasn’t changed.

It’s left little time for field visits. The Bhiwadi office is expected to conduct about 460 inspections every quarter but manages to conduct only 40-50 per cent of them. Logistics are another blocker. There are not enough vehicles, drivers, or technicians to accompany officers for sampling. Officials say there’s only one driver and sampling van at their disposal.

Training programmes usually circle back to the “basics” of the law and procedures, according to Pathak.

“What we lack are region-specific trainings that help us diagnose local problems and build context-specific solutions, rather than generic, one-size-fits-all approaches,” he said.

Inside the bottlenecks

From labs to monitoring infrastructure, the entire system is groaning under pressure, say pollution board officials.

The lab’s four staff cannot test for heavy metals or hazardous pollutants because the facility doesn’t have the required equipment, critical for an industrial area like Bhiwadi.

“For metals testing, everything goes to Alwar,” said senior scientific officer and lab- incharge Rohit Meena. “Our lab should be upgraded. A microbiology lab is proposed too, but it will take a while.”

Then there is continuous monitoring, a system meant to make pollution control automatic, real-time, and transparent. In reality, it is neither. More than 360 factory units are required to install Continuous Emission Monitoring Systems (CEMS), but officers estimate less than 40 have complied. The last date for compliance is 31st December.

“We can’t monitor 24×7, it’s just not possible,” added Meena.

Meanwhile, illegal units continue to function and toxic sludge covers large stretches of the roads.

In a report submitted to the National Green Tribunal on 1 May 2025, the RSPCB acknowledged that multiple illegal kilns were operating near the Rajasthan-Haryana border, several within Bhiwadi’s jurisdiction. These units run without mandatory consent of the state pollution board, in clear violation of the Water Act, the Air Act, and the Environment Protection Act. The filing confirms what residents have said for years: entire clusters of polluting units operate in plain view but untouched by regulators.

This area was never planned as an industrial township. It’s basically a catchment area where industries started coming up and people began settling. The concentration is too high, and the geography works against us

-Amit Juyal, senior environmental engineer & regional pollution officer

Another unsightly failure is visible on Bhiwadi’s waterlogged roads, where oily industrial muck collects in thick patches — a result of drainage systems that haven’t kept up with the industrial sprawl. The “effluent stream” stalls two-wheelers, worsens traffic jams, and forces pedestrians to pick their way through chemical-tinged puddles. The industrial wastewater from Bhiwadi also flows into neighbouring towns like Dharuhera in Haryana, with the NGT even fining the Rajasthan government Rs 45 crore for it a couple of years ago.

In August 2025, the NGT again pulled up the RSPCB again after activist Haider Ali filed a case about untreated industrial effluent flowing from units in Bhiwadi’s Chowpanki and Khairani, among other places. Around the same time, a Central Pollution Control Board inspection identified 40 industrial units in Rajasthan as non-compliant with effluent discharge standards.

Officers point to deep structural deficits. There’s no dedicated research and development wing to analyse trends, innovate solutions, or conduct region-specific studies. Formalised training systems are missing. And then there’s the elephant in the room—an industrial landscape without the bedrock of planning.

“This area was never planned as an industrial township,” said Juyal. “It’s basically a catchment area where industries started coming up and people began settling. The concentration is too high, and the geography works against us.”

The machinery of pollution

At several spots near the industrial estate, stagnant, inky-blue wastewater pools spill onto the road. The smell arrives before the sight. A temple is close by, and a primary school is about 500 metres away.

“It has been like this for years,” said a factory owner, who runs a mid-sized fabrication unit. “There is chemical drainage everywhere. Why doesn’t the Board come and fix this?”

But RSPCB officials claim this is beyond their ambit—they can issue directions but execution is not in their hands. Drainage and stormwater channels fall to the Nagar Parishad and the Rajasthan State Industrial Development & Investment Corporation (RIICO), they say.

It’s much the same story with air pollution. Pollution board officials allege that their directives tend to vanish into the ether. The machinery of pollution control in Bhiwadi is a chain of deferred responsibility.

“Road dust is the main source [of air pollution],” Juyal said, echoing the findings of a 2020 IIT Kanpur study that was submitted to the RSPCB. “We issue directions, but many times the action has to be taken by RIICO or the Nagar Parishad.” His colleague Ankur Pathak put it more bluntly: “Everyone expects enforcement, but it doesn’t happen.”

RIICO officials, meanwhile, claim that funds are a constraint. A recent RSPCB directive to mend a broken road to reduce dust emissions could be fulfilled only partially.

“We had funds to repair only one stretch,” a RIICO official said.

But perhaps nothing captures the institutional sluggishness as much as the long, uneven life of the Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP), meant to treat industrial wastewater before it goes back to units.

A 2017 CAG report noted that treated effluents were being pumped via a pipeline to the Sabi River or flowing onto open lands in industrial areas. In some cases, treated water mixed with untreated hazardous discharge from factories, defeating the CETP’s purpose entirely.

Set up by RIICO and the Bhiwadi Integrated Development Authority (BIDA) in 2004, the plant was later handed over to a local “Samiti” of industrial units and eventually formalised as the government-funded Bhiwadi Jal Pradushan Niwaran Trust.

The plant, which handles a heavy mix of industrial wastewater and spent acid, is located right next to a busy residential neighbourhood. Star Hospital and the Lemon Tree hotel are less than a kilometre away and an industrial sewage plant operates only 200 metres from its gate.

We pay for CETP upkeep, but it never runs efficiently. Half the time the tanks overflow. If the system doesn’t work, how do you expect industries to trust it?

-Bhiwadi factory owner

Satinder Singh Chauhan, chairman of the Bhiwadi Jal Pradushan Niwaran Trust, made no bones about his frustration.

“If there were a way out, I’d leave tomorrow,” he said with a tired half-smile. “No one volunteers for this post. Everyone knows it’s a headache.”

On one hand he is fielding notices from the Pollution Control Board, on the other he is grappling with industries that don’t comply. And then there is the constant fear that untreated effluent will find their way into neighbourhood drains.

Membership fees and treatment charges — about two rupees per litre — add up quickly, and for smaller units, compliance becomes something to dodge, according to him. Complaints of factories draining untreated water at night tend to spike in the monsoon.

“Finding who does it is nearly impossible,” he added.

Across the road, a factory owner pointed to the other side of the same problem.

“We pay for CETP upkeep, but it never runs efficiently. Half the time the tanks overflow. If the system doesn’t work, how do you expect industries to trust it?”

Environmental clearances, he laughed, are a “paperwork circus”, adding that clearer guidance, simpler norms, and more coordination among agencies would be “helpful”.

The consent process is cumbersome not just for industries but for us as regulators. Most applications come in with half-filled forms or missing technical details. Companies usually hire consultants, but even then the gaps persist. We can’t ‘fix’ their forms, all we can do is send them back and point out what’s missing. That makes industries feel like nothing moves at the Board, and they end up spending more money on consultants, while we can’t approve anything without complete technical undertakings.”

When few others following the norms, the costs of compliance can seem both high and futile.

The owner of the mid-sized fabrication unit said he recently upgraded his diesel generator set to comply with new emission norms but doesn’t particularly see the benefits.

“Our genset wasn’t even that old,” he said, running a hand along the new machine. “Still, we spent over a lakh on upgrades. And honestly, I don’t know how much it helped. The industries around us keep violating norms. If everyone doesn’t follow the law equally, what difference does one compliant generator make?”

In industrial clusters where dozens of units compete on razor-thin margins, the ones who follow rules often lose out to the ones who quietly don’t. The factory-owner cited stone crushers as an example. Under GRAP, they’re supposed to halt work on high-pollution days, but most don’t.

“They work at night instead. If the law isn’t enforced uniformly, no industry will follow it because it will impact pricing.”

Small towns in the red zone

Bhiwadi is the local expression of a national crisis. Small industrial towns have become big-hitters in pollution. CPCB inspections, CAG audits, and parliamentary committee reports repeatedly flag shortages of environmental engineers, lab technicians, and monitoring infrastructure across India.

A 2021 Centre for Science and Environment report found that many of the 88 industrial clusters flagged as polluted in 2009 by the central and state pollution boards had even worse air, water, and soil contamination in 2018. Air quality deteriorated in 33 clusters, including places like Mathura, Bulandshahr-Khurja, Moradabad, and Tarapur. Last year, Byrnihat, an industrial town in Meghalaya was ranked the most polluted city in the world by the IQAir report. Dharuhera in Haryana is another contender.

‘Success stories’ do occasionally surface, though they come with caveats. Vapi in Gujarat is one example. The chemical and industrial hub made international headlines as global “toxic hotspot” since the early 2000s but reportedly effected a “turnaround” starting 2010. The Gujarat Pollution Control Board started tightening enforcement and served closure notices to multiple non-compliant factories in that period, and the Common Effluent Treatment Plant also went through a Rs 464 crore upgrade. Subsequently in 2016, the central government lifted the moratorium on setting up and expanding industries.

To break this cycle, three shifts are essential—compel RIICO and local bodies to act within fixed timelines, trigger joint enforcement, have funding for those special projects monitored and released by the state pollution board

-N Manoj Kumar, a senior analyst at CREA

However, it’s no pollution-free haven. In 2023, Down to Earth reported that the pollution boards found that treated effluents from Vapi CETP didn’t meet safety standards. Additionally, it said that the industrial area’s comprehensive pollution index score wasn’t calculated in five years. This year, Vapi recorded among the worst levels of air pollution in Gujarat.

Varanasi, another up-and-coming industrial hub, also suffers from questions around data. ThePrint reported last year that even though its air quality had showed a remarkable improvement, there were long gaps in monitoring data, missing readings from several stations, and uneven baselines.

As for Bhiwadi, it has only two Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations, which is woefully inadequate for a city of its size, industrial load, and pollution levels. Experts recommend there should be at least six.

Vehicular pollution adds another layer. With almost no public transport, most residents rely on cars and two-wheelers for daily travel, pushing more exhaust into already foul air.

According to the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), air pollution reduces life expectancy by an average of 2.6 years and contributes to 30 per cent of all premature deaths. Research published in The Lancet found that in 2017 alone, air pollution caused 1.24 million premature deaths in India, the equivalent of a child dying from pollution-related causes every three minutes.

What’s the solution?

As with many things in India, things go wrong because of scattered and lethargic governance.

Coordination among agencies is weak, with the PWD, RIICO, the Nagar Parishad, and the Bhiwadi Integrated Development Authority (BIDA) operating with overlapping mandates that slow projects and create chronic miscommunication, according to Chauhan.

“RIICO’s limitations and the council’s strained finances compound the problem,” he added.

Regional pollution offices also work with limited delegated powers. They issue directions, but enforcement sits with different bodies — RIICO for infrastructure, the Nagar Parishad for drainage and waste. Pollution becomes a parcel passed from hand to hand, until it disappears into the cracks.

“To break this cycle, three shifts are essential—compel RIICO and local bodies to act within fixed timelines, trigger joint enforcement, have funding for those special projects monitored and released by the state pollution board,” said N Manoj Kumar, a senior analyst at CREA and one of the authors of the 2025 study.

He added that a shared dashboard between RIICO, the Nagar Parishad, BIDA, RSPCB, and the district administration, updated monthly, is crucial. “Without ownership, no one is accountable.”

Given the overlap of industrial and residential zones, he said Bhiwadi requires a mandatory health-impact assessment every three years.

“They need annual audits of air, water, soil, and health. Within the team, there also must be data analysts and strategists who can effectively work on problem solving,” he added.

Cough, coryza, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pharyngitis, lower respiratory infections. And skin issues: eczema, acne, scabies. These spikes are real

-a Bhiwadi doctor

On the issue of lagging permits sucking up the pollution board’s time, Pathak pointed to Punjab as a model of efficiency.

“The Punjab Pollution Control Board appoints chartered engineers and certified professionals to help industries prepare technically complete applications,” he said. “This saves the board’s time on back-and-forth corrections and speeds up approvals.”

However, some critics do not agree with the argument that Bhiwadi’s pollution governance inefficacies are about manpower or technical capacity. The real problem is one of intent and political will, according to Debadityo Sinha, senior resident fellow at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and lead of its climate and ecosystems team.

“If the state wanted stronger enforcement, they would increase staff and empower officers. They simply don’t. For example, the GST system works because there is political will and administrative pressure. Environmental regulation gets neither,” said Sinha, who has over 12 years of experience on issues related to environmental and wildlife protection. “If the state started valuing clean air the way it values tax revenue, compliance would improve overnight.”

Another aspect of the problem is lack of transparency around pollution metrics. Despite having single-window clearance and everything online, emission and discharge data remains inaccessible.

“The data exists, the government just doesn’t want to publish it. If a factory near my house is emitting beyond limits, I should be able to see that data live. The technology to monitor industries in real time already exists, but enforcement remains reactive, not preventive,” Sinha said.

One of the CREA report’s major recommendations was that satellite observations should be integrated with a denser and better-sited monitoring network in industrial areas. And that this information should be made public.

“Establishing protocols for validation, periodic updates, and public dissemination of satellite-based estimates will strengthen transparency and enable real-time decision-making in areas lacking ground monitors,” it said.

Also Read: How Chenab went from the river of love to the restless ticking time bomb

A daily pall

At a small clinic near Bhiwadi’s old industrial area, a physician ticked off the cases he sees like items on an inventory sheet.

“Cough, coryza, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, pharyngitis, lower respiratory infections. And skin issues: eczema, acne, scabies. These spikes are real,” he said, asking to remain anonymous.

The months he worries most about are April, May, September, and October, when heat, humidity, and trapped emissions combine into a suffocating brew. Industrial workers, he noted, face the worst of it.

“Chemical, pesticide, rubber, paint units… those exposures stay in the lungs. They accumulate,” he said, adding that some patients know the cause, while others only sense that the air around them is making them sick.

It’s not just health, it affects learning too. If a child has been unwell and absent for three or four days, they miss the basic concepts

-Uma Khandelwal, teacher in Bhiwadi

He said no government agency had ever approached him for data, surveys, or any study linking air quality to disease patterns, and that he did not know of any epidemiological project, past or ongoing, in Bhiwadi. The pollution board office also confirmed there was no such study.

“Health impact studies are treated as non-urgent because evidence of harm would work against the government, and without evidence the system keeps pretending there is no real harm,” Sinha said. Even among residents, though many complain about pollution, there is no cohesive mobilisation or protest.

Fifteen years ago, 35-year-old Uma Khandelwal moved from Delhi to Bihiwadi hoping for cleaner air and a gentler pace of life. What she found instead was a town suspended between aspiration and abandonment. Her own commute is its own reminder of how broken things are. Her school sits along the Alwar bypass road, a stretch with almost no public transport. She has no option but to drive herself every day. But it’s when she’s standing in class that she’s really hit by the contradictions she lives every day.

“I’m doing everything in my power to teach them well but what does it matter if they can’t breathe clean air?”

What worries her most is how quickly infections among children spread when immunity is already strained by the air they breathe. The illnesses go beyond the usual colds. She said there are more cases of hand-foot-mouth disease and even mumps. The pollution casts a pall on education as well.

“It’s not just health, it affects learning too,” Khandelwal said. “If a child has been unwell and absent for three or four days, they miss the basic concepts. Then nothing in the chapter makes sense to them.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)