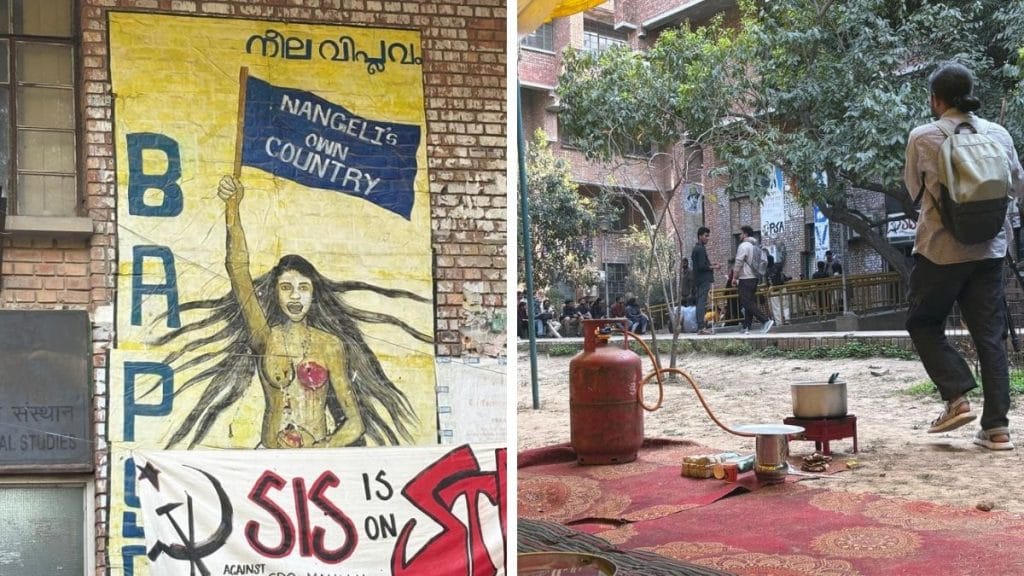

New Delhi: Outside the Jawaharlal Nehru University School of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies, students have gathered—some sitting on the stairs, some standing, others cross-legged on the ground—to protest against the surveillance on students.

A microphone on a stand is set up, cameras ready, as the open-air lecture by Jayati Ghosh, an economist and former JNU faculty, is about to begin.

The gathering is part of an ongoing strike against the university administration, triggered by the installation of a facial recognition system at the university’s Dr BR Ambedkar Central Library and the subsequent rustication of five student leaders.

Ten years after the protests led by Kanhaiya Kumar saw open-air classes and debates, another movement is unfolding at JNU. At the heart of it all is what appears to be an irreversible transformation of the liberal arts university in just one decade. If the ‘Azadi’ anthem took root in a JNU protest in 2016, this movement is about a different kind of freedom—freedom from surveillance.

The latest friction point emerged when JNU Vice-Chancellor Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit used the term “victim card” when talking about Dalit individuals, triggering calls for her resignation.

The students are demanding that the rustication orders be revoked, UGC guidelines be enacted, and acting librarian Manorama Tripathi be removed from her post.

“Revoking our rustication is the lowest demand. The real fight is to reclaim what has been taken from us in the last ten years—access, rights, and campus autonomy. Whether it’s ending criminalisation of protests through the CPO manual, restoring the dismantled GSCASH, building the library annexe, or asking for the resignation of the VC—these are all part of the struggle,” said Nitish Kumar, former president of Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union (JNUSU).

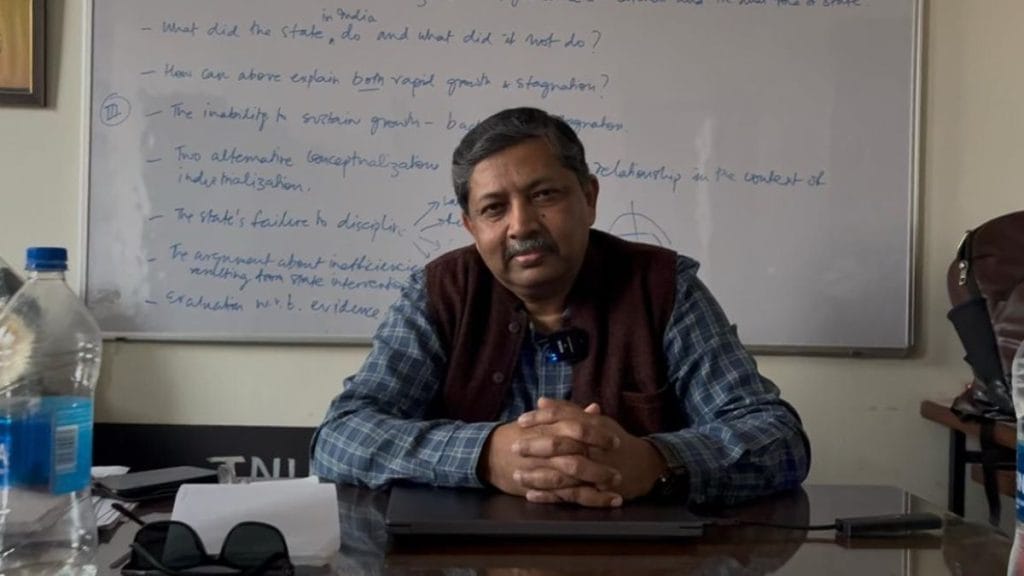

For Surajit Mazumdar, president of JNU Teachers’ Association (JNUTA), the administration’s action signals something far more sweeping than a disciplinary measure.

“When you are rusticating the office-bearers of all four unions, you are saying: we will not allow the union to function. You are punishing the entire student body because you want to finish the body,” he alleged.

A new wave

Ever since five JNUSU students were rusticated for two semesters and fined Rs 20,000 each for vandalising the new facial recognition system at the central library, several students of the university have been on strike, camping outside the JNU School of Language, Literature and Cultural Studies (JNU SLLCS).

The newly elected student’s union—Aditi Mishra (president), Gopika (vice-president), Sunil (general secretary), Danish (joint secretary), and Kumar—has openly rejected the facial recognition system at the central library and vandalised the structure after repeated pleas against the installation.

In August last year, Kumar heard that a biometric system, reportedly worth Rs 20–30 lakh rupees, was being installed and went to the central library to verify it. Once confirmed, students immediately began protesting.

After two-and-a-half hours, the installation was stopped. The Union demanded clarity from the administration and asked to form a committee to consult all stakeholders.

“Despite this, the authorities resumed the installation the very next day. On 21 August, we held an open house with students, discussed the issue, and decided we did not want this biometric system,” he said.

That night, the JNUSU President, Vice President, and General Secretary sat in an indefinite sit-in. Even though the then joint secretary from ABVP refused to support them.

The following day, the administration resumed the installation in the presence of Tripathi. When students attempted to intervene, the Delhi Police was immediately called to prevent them. The main library doors were locked, and with no other options, the students tried to break in, leading to a few broken glasses.

Tripathi refused to comment on the matter, citing “orders from above”.

Kumar alleged that installation resumed during the election period, when the union was functioning in a caretaker capacity.

“On 21 November, we asked the security guards to call the acting librarian, as well as the registrar, but they did not come. Students were being forced to register their faces to enter the library,” Kumar said. “In response, we calmly removed parts of the machine, demanding answers about the system’s software, data handling, fire safety clearance, and the committee.”

An inquiry was conducted against Kumar and several others. Usually, notices are issued before semester registration so that fines can be imposed. But in this case, the notice was issued on 2 February, at the same time as nationwide student protests and a stay on the UGC equity guidelines. The union had also called for a march on 3 February to protest the stay on the guidelines.

Kumar alleged that the entire episode was as part of a broader pattern of administrative targeting and institutional restructuring.

“Recent VCs are not here for JNU’s improvement. Mamidala Jagadesh Kumar tried hollowing out JNU from 2016-2021. He ended the entrance model, dismantled the Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment (GS Cash), and later received Padma Shri and a UGC chairperson post. The current VC seems to compete with him and aims to damage JNU further,” Kumar alleged.

Referring to the 2023 CPO manual, he added, “I had a fine of Rs 29,000 myself. Ranvijay, AISA president, faces fines totalling at least Rs 60,000 each semester. These measures are there to punish the activists.”

The strike had been going on for about two weeks, triggered by repeated demands to halt the installation of the biometric system. At that time, Kumar was the president of JNUSU.

ThePrint has reached out to the administration, but it is yet to receive a response.

Also read: Kolkata biryani wars get 2 new challengers in Dada Boudi, Hanglaatherium

A divided faculty

Across campus corners, on lawns and in canteens, conversations carry a mix of frustration and nostalgia. Students and professors alike speak about what JNU is becoming. Some faculty members who once studied here say they feel the change most acutely.

“We are breathing fearful air now,” said a PHD scholar at JNU.

For many, the concern is that administrative power often outweighs academic priorities, and that investments in high-visibility technology masks deeper institutional decay.

“The expenses on field trips, on seminars, on books and journals in the library—all these are being cut,” said Mazumdar. “Over the years, essential academic spending has nearly halved, while salaries and pensions continue to consume a growing portion of the budget. If you look at total expenditure, it’s not always clear that cuts are actually happening—the money for salaries is still coming in. But for everything else, the resources are shrinking.”

The library, once open and accessible to all, faces surveillance, even as roofs leak, walls crumble, and classrooms struggle with minimal maintenance.

“When these serious issues exist, there is no money to fix them. And yet, money is spent on unnecessary technology. Guards already check IDs; there was no need for FRT,” he said.

He alleged that the issue extends beyond finances to the concentration of authority in the Vice-Chancellor’s office. Decisions that were once collective, involving academic councils and elected representatives, have become top-down and autocratic, he claimed.

“Meetings of the Academic Council or the Executive Council have been reduced to formalities. You read the agenda online, you say ‘pass,’ and that’s it,” he said.

This centralisation, Mazumdar said, has direct consequences for students. Rustications and other disciplinary actions often go beyond legal limits and target those who oppose the administration.

He also highlighted the erosion of institutional mechanisms designed to safeguard fairness. GSCash had long provided checks and balances, involving elected student and teacher representatives to ensure impartiality. Yet in the name of UGC regulations, GSCash was quashed and replaced by Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs).

Despite these challenges, Mazumdar emphasised the university’s enduring commitment to learning and intellectual freedom. He supports students who protest, hold open-air classes, or experiment with alternative teaching methods.

“We respect the students’ decision. Some education can happen in open-air classes, and if students request it, we honour it,” he said.

The debate has exposed differences within the faculty over the legitimacy of the protest and the methods adopted. Not all professors have agreed that the action of vandalism align with the university’s ethical and academic values.

Professor M Christhu Doss has strongly condemned the recent vandalism at the central library. Invoking Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of universities as bastions of humanism, reason, tolerance, and the pursuit of truth, the professor argued that such acts of destruction directly undermine the fundamental purpose of a university.

“Does an emotional surge justify the vandalism of university property? Is it not a grave breach of ethics to damage an institution meant for posterity? Can such acts be defended even if some students condone them? And can calculated destruction of this sort ever be considered a democratic gesture?” he said in a statement.

Also read: Pahadis are moving from restaurant kitchens to bartending. ‘Community has tasted success’

‘Don’t want to learn from YouTube videos’

Sitting on the stairs at the entrance of SLLCS, Mishra described the culture of the Central Library, where students often study deep into the night—sometimes until two, three, even four in the morning. It has long been a campus tradition: reading for hours, debating ideas, stepping out for tea, and then returning to their books.

“But this ideology wants to stop all learning, impose curfews in the library, curfews in women’s hostels, and put surveillance everywhere,” said Mishra.

For her, the issue is only ideological and material. Inside the same library that symbolises intellectual freedom, broken windows let in harsh winter air. Rare and expensive old books lie exposed to sun, dust, and rain. The crisis is not about a lack of resources, but about priorities. It is about who gets access to quality public education and under what conditions.

In late September 2025, JNU signed a memorandum of understanding with the Siddhanta Knowledge Foundation. The foundation’s Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) online courses had already been introduced at the undergraduate level in 2024 under NEP 2020.

On 2 February, the SLLCS Council called for a strike, demanding that the foundation be “booted out” and the MoU rolled back. Protesters accused the move of pushing privatisation and embedding “Manuvad” through IKS courses.

“We don’t want to learn from videos on YouTube. We want to learn from live, engaged professors,” she said. “Our children deserve the best. Our windows shouldn’t be broken in winter. Our library shouldn’t rot,” said Mishra.

Her argument extends beyond infrastructure. She insisted that the fight is about preserving a space where students are encouraged to question authority, sharpen critical thinking, and access knowledge freely.

“If they succeed in privatising JNU, it will no longer be a space for real education. It will become a playground for corruption and profit,” she said.

She said that the government and elite forces resent JNU precisely because it opens the doors of quality education to middle and lower-class students, Dalits, Adivasis, and other marginalised groups.

“They would rather see their own children in expensive private universities like Galgotia, where education costs lakhs, and access can be controlled. This is not about reform — it is about deciding who deserves education and who does not.”

For some on campus, the sight of students studying on lawns and staircases is not unfamiliar—it carries the memory of earlier confrontations between authority and dissent.

N Sai Balaji, a former JNUSU president, situated the strike within what he described as a longer history of institutional neglect. During his tenure, he recalled, the university announced an 80 per cent fund cut.

“From then, till now, there was no serious promise to strengthen the library’s funds, expand reading rooms, or improve infrastructure. Yet, the administration appeared ready to invest substantial sums in systems that restricted access rather than broadened it,” he said.

He drew a direct parallel to 2016, when the sedition case against Kumar, Umar Khalid, Anirban Bhattacharya, and others triggered a massive campus movement. He said that it is because JNU is a campus of ideas and any ideological attack is against the very nature of this campus.

Back then, the university went into lockdown. But students refused to let academics collapse. The union created rosters assigning lawns and open spaces for classes; professors walked to these makeshift venues and took attendance themselves. Even amid protest, dissertations were written, lectures delivered, debates sharpened.

“The union filed a report alleging that non-teaching appointments involved payments running into lakhs, with candidates hired outside the merit list and preference allegedly given to individuals from particular villages,” Balaji said, adding that this was not an isolated instance.

“Earlier, foreign quota seats were allegedly allotted to Indian nationals in violation of norms. The corruption continues. Yet we are the ones lectured about discipline and academic integrity,” he claimed.

Also read: ‘Was hoping to celebrate his UK admission, now just want justice,’ Dwarka crash victim’s mother

‘Middle path could have been worked out’

Mishra stood firm at the centre of a tense standoff. Female guards arrived behind a security inspector, trying to disperse the strike, but she did not flinch.

“Bring a female inspector first, then we’ll talk. Go tell the Vice-Chancellor,” Mishra demanded, her voice echoing across the crowd. “At night, male guards speak roughly—why isn’t a female inspector here?”

When security personnel began filming, students shot back: “You’ve got enough content. Now leave.”

Even as the strike continues, the unrest on campus is not confined to one student organisation. The ABVP has also raised objections to aspects of the administration’s policies, particularly the CPO manual.

The CPO manual has resulted in fines of over Rs 5–6 lakh being imposed on many of us,” said Vikas Patel, State Joint Secretary of ABVP. “There are several cases where proper inquiries were not conducted. Many students couldn’t register for their by-semester and were forced to leave their degrees midway. We have protested against the CPO manual multiple times.”

He added that when the manual was introduced three years ago, the JNUSU had opposed it, but said their current protest intensified only when their own positions were under threat. “However, ABVP had protested even then,” he said.

On the face recognition system, Patel said the administration should have consulted students before making a decision. At the same time, he criticised the vandalism of the machines, saying it was not justified. “A middle path could have been worked out,” he added.

For those gathered outside SLLCS, the fight is no longer only about a facial recognition system or a set of fines. It is about the character of a public university — who it serves, how it is governed, and whether dissent and debate will remain central to its identity in the years to come.

Mishra claimed that institutions like JNU are being pushed aside to make way for expensive private campuses such as Galgotias University, where access depends on money, not merit. “That is why they want to shut spaces like this. “Because when education is affordable, students learn to question power,” she said.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)