Tawang: At 95, Bumpa Tshering from Lumpo village in Arunachal Pradesh’s Zemithang Circle is ready to help the government of India once more. He did it as a young man in 1962 when he walked from his hamlet towards the Dhola Post near the border — moving “ration and goli (ammunition)” for the Indian Army during the India-China war.

But just last week, China released a new “standard map”, which included Arunachal Pradesh and the Aksai Chin region as part of its territory. The move has not gone down well with Tshering and other members of the Monpa community in the Tawang district. They reaffirm their commitment to India.

“Our spirit to serve the nation remains the same. If the government wishes to develop this area, our Monpa community will help in whatever way we can,” said Tshering, gazing at the Buddhist prayer flags fluttering in the wind.

Life has remained the same since the war, except now there are more monkeys and wild boars that have been destroying the crops, he says. But the vibrant winds of change are blowing into his hamlet in the mountains—and Bumpa Tshering is waiting. He wants hospitals, schools and solar-powered fences.

The younger members of the community are restless. They want to be part of an India that sends rockets to the moon and have uninterrupted access to 4G.

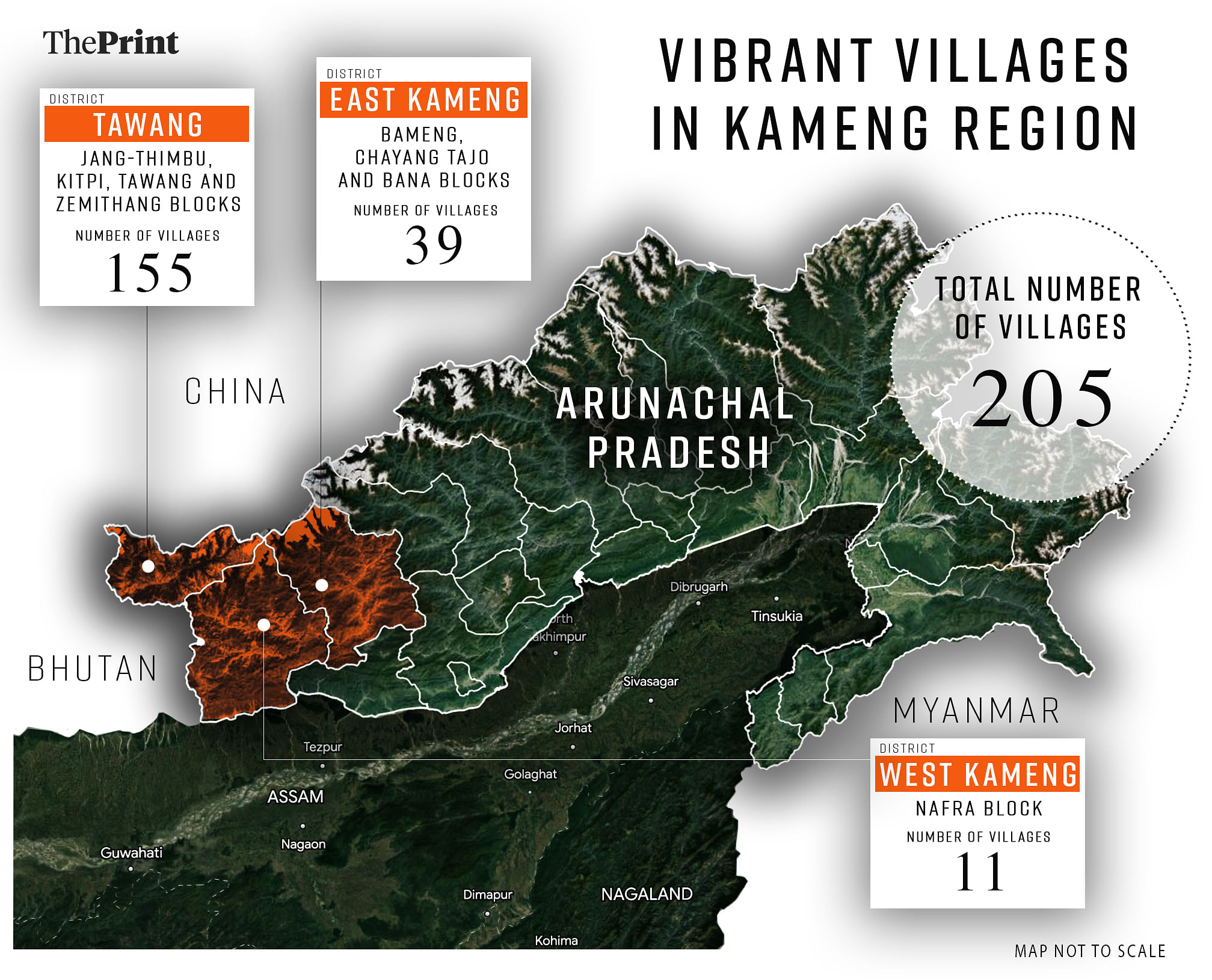

The drum rolls for development have been sounded in Arunachal Pradesh with the Narendra Modi government’s Vibrant Villages Programme in February 2023 — as a way to counter China’s flexing of muscles. Lumpo is among the 205 habitats in the border districts of East Kameng, West Kameng and Tawang districts that have been selected. And residents in these border villages and towns have a laundry list of needs.

From the Mahayana Buddhist Monpa tribe or the Nyingmapa Buddhists in Zemithang to Chayang Tajo village’s Nyishi community in the East Kameng district that worships Donyi-Polo (the Sun and Moon), there is a clamour for better roads, weatherproofing systems, army jobs and higher education institutes. In the more remote villages, people want roads and connectivity to bridge the chasm to the rest of the country.

In the border village of Laching Bagang in the Chayang Tajo sub-division — a three-day ride from Lumpo village—residents want electricity and a cell tower to power up their mobile phones. And in nearby Jayang Bagang village, people are lobbying for a veterinary clinic. The seemingly prosperous swathes of paddy fields and steps of maize farms and fish ponds hide a darker story of cattle dying of diseases. A few kilometres away in a Puroik hamlet, villagers are asking for a bridge and better roads.

They have been left behind for decades, and now they are betting on the Vibrant Village Programme to open new doors. The initiative was announced this year with a Rs 4,800 crore allocation for the financial years 2022-2023 to 2025-2026, of which Rs 2,500 crore will be used for roads.

In April this year, after China attempted to rename Zemithang among 11 regions in Arunachal Pradesh, Minister of Home Affairs Amit Shah spent a night at the remote Kibithoo village, India’s eastern-most post, where he urged everyone to drop by for a visit.

“Our policy is clear, we want peace with everyone. But not an inch of our territory can be transgressed, and there can be no compromise on the integrity of our soldiers and our borders,” Shah had declared.

The development initiatives will serve the dual purpose of enhancing border security and improving infrastructure. But for villagers, it also holds the promise of stemming the tide of migration from the villages to urban areas.

Biaro Sorum, assistant deputy commissioner of Chayang Tajo sub-division, is on board with the government’s plans to develop some of the villages into tourist hotspots while ensuring that infrastructure from road to education and health services are provided for residents.

“We have opportunities for adventure sports, trekking, developing sites around waterfalls, paragliding — all under the Vibrant Villages Programme. The border people should be self-sufficient so that migration into town areas comes to a stop,” he says.

Also read: Arunachal’s Kaho is set to become India’s first vibrant village. But China is miles ahead

Army-civilian bonhomie

In Zemithang, Dechin Pema and three of her friends are working toward opening their bakery-cum-cafe. For two weeks in July, the four women learned how to bake bread, pizza, pattice and sweets as part of a soft-skills training initiative by the Indian Army. They received their certificates and have been assured by the Army of all possible help. This will be the first bakery run by a group of Monpa women in Zemithang.

“We are hoping to start it soon. But we wish there was a bank here because the nearest one at Lumla town is about one-and-a-half hours away,” says Tenzin Tseyang, a graduate from Bomdila Government College in West Kameng district.

Even before the Vibrant Villages Programme was announced, the Indian Army had been imparting soft skills training to residents across villages and towns in Zemithang Circle, and supporting them with entrepreneurial ventures.

The bonhomie between the Indian Army and civilians is apparent in the border areas of Arunachal Pradesh. Children roaming around the villages are happy to see Army vehicles, and raise “Jai Hind” slogans as they pass by. Villagers gladly open up their houses to soldiers travelling along the route, and even offer them food and tea.

The bakery isn’t the only talking point. Forty-three-year-old Thinley Sombu and four other men from different villages in Zemithang Circle have completed an automobile repair training workshop sponsored by the Indian Army.

“Some of us own a vehicle, but we didn’t have basic knowledge about automobiles until now. I request the Army to conduct an advanced training module extending for three to six months in addition to this basic course,” says Sombu. His friend, 39-year-old Tenzin Phuntso, who also participated in the workshop is ready to open ‘Yong Ten Auto Garage’, a tyre repair garage-cum-car wash centre at Zemithang Bazar, with the help of the Army.

The state government and the Army have also been organising medical camps for the yak rearers in remote locations. The local Brokpa community in Tawang recently attended a veterinary camp organised by the army during the Chachin Grazing Festival on 14-15 July. This relationship works both ways: some of the traditional grazing grounds are close to the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that demarcates the territories under control of India and China.

The Army has stationed a doctor at the Primary Health Centre (PHC) in Zemithang town headquarters where patients from nine villages can avail medical care. It is also planning to launch a joint initiative with NGOs to offer free surgeries at select hospitals.

As part of the Modi government’s plan to develop the region into a tourist hotspot, the Army with the help of the civil administration also conducted a workshop for the homestay owners of Zemithang earlier in June. There are 14 homestays in Zemithang, but this may rise if tourists heed the government’s clarion call. With this in mind, participants were taught the basics of interacting with guests, and housekeeping skills.

A robust tourism infrastructure will not only benefit casual visitors and adventure seekers, but also the thousands of Buddhist devotees, many from Bhutan. The devotees descend to the 12th century Gorsam Chorten stupa in Zemithang every year during the annual festival in March.

The Army’s ties with the people living in the Zemithang Circle or Valley—as it’s called—run deep. Geography and proximity to the LAC has had a part to play in this. The scenic valley is located on the western-most frontier of the Kameng region along the banks of the Nyamjang Chu river, which flows into India from Tibet at Khinzemane. From there, it flows further south through Lumla town, the sub-district headquarters, where it joins the Tawang Chu river before entering Bhutan.

For villagers, Khinzemane is a special place. It’s where the 14th Dalai Lama crossed over to India on 31 March 1959.

In promoting tourism along the northern borders, the government of India has won hearts of the Monpas in Tawang and West Kameng districts by developing the area around the lesser-known Chumi Gyatse Falls. Colloquially called the ‘Holy Waterfalls’, it is a collection of 108 waterfalls, just about 250-350 metres from the LAC near the Yangtze sector, one of the disputed regions along the McMahon Line demarcating the Tibet Autonomous Region of China and Arunachal Pradesh.

It’s a blessing to have the waterfalls in Indian territory. Only 25 per cent of the falls are visible from China.-Lama Sange

It’s a three-hour drive from Tawang, and a 25-minute walk along the banks of the fast-flowing Tso Chu river through a flowering wooded patch. The Holy Waterfall is revered by the Monpas on both sides of the border.

“It’s a blessing to have the waterfalls in Indian territory. Only 25 per cent of the falls are visible from China. Earlier, when we used to travel to Chumi Gyatse, the Monpas of Cuona County [in Tibet] could be seen near the border,” says Lama Sange from Lhou circle, Tawang district. They would urge the Indians to sprinkle holy water at them because they could not access the waterfalls.

“Now, we don’t see them anymore,” Sange adds.

Also read: Tawang face-off: Locals of Arunachal’s Zemithang exude confidence in Indian Army and Centre

Embracing development

The July sun streams in through the windows of the sturdy Bra-rong, the traditional house made of red soil and stones where Tshering lives.

The statue of Guru Padmasambhava, one of the founding saints of Tibetan Buddhism, towers over the Lumpo hamlet with its 350 villagers. This village has remained tobacco-free for 35 years, and they wear it like a badge of honour.

Warming up by the furnace with a cup of Cha-Za, a salt tea made from Yak milk, Tshering points to the power lines running through Lumpo.

Electricity came to Lumpo and other villages in Zemithang in the 1960s along with roads, and water supply as part of the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana. Today, much of the road work is undertaken by Border Roads Organisation. But the power lines have been dead for days after a spate of torrential rains in the region.

The solar lamps have proved useful, says Tshering, as he shares tea and a plate of Ra Nelap, a traditional snack made with flour. “The government can work on technology for a weatherproof system so that lights don’t go off in rain or storm,” he adds.

Nawang Chhota, the village chief, says that the only loss they faced was in 1971 when farming lands were washed away due to floods in the Nyamjang Chu river. “There has been no heavy flood since,” he says.

With regular military movement, the road conditions have improved over the past one year. The roads to Lumpo and Khinzemane were black-topped last year.

This Trans-Himalayan area just 10-12 km from the Tibetan border is piercingly beautiful. Nomadic yak rearers from the Monpa community raise their livestock here, while women in their traditional woollen red caps called seir-sha leave early in the morning to work in the fields or on road connectivity projects. They are armed with sickles and pick-axes, some with babies slung across their shoulders.

Besides farming and rearing yaks, the Monpa men and women in Zemithang who are employed in government projects earn Rs 550 a day. It’s considered more profitable than other jobs.

But it is not enough to make the youth stay in the region. With the dearth of colleges, and professional institutes, many leave for the nearest town or other Indian cities to continue their education.

We need more secondary schools and better health facilities. For any medical emergency, we have to go till Tawang–village chief

Even children in remote villages do not stay home for studies beyond primary school. With only seven government schools in Zemithang, (primary, upper primary, residential, and a recently upgraded secondary school) they often have to leave their homes and live in hostels to continue their studies.

“We need more secondary schools and better health facilities. For any medical emergency, we have to go till Tawang,” says Chhota.

The Government Primary School near Gorzam, which was established in 1964, and upgraded to secondary level in April this year, is abuzz with activity. New classrooms are being constructed for Classes 9 and 10.

“Some students who cannot afford to pay rent or hostel fees while pursuing higher studies away from home are forced to drop out. Some lose interest in studies as they move to other places, as far as 50 km from home,” says Dorjee Lopsang, the school headmaster.

At the Government Residential School in Shocktsen, also in Zemithang, students line up to sing the national anthem. After the assembly, the headmaster, Tenzing sets out to collect firewood from the jungle with the help of villagers. He has to feed 58 boarders from Classes 1-8.

“We are in need of firewood for cooking meals. It becomes difficult sometimes. We wish the road to the school is improved along with network connectivity. Often, because of the slow internet, we fail to send reports to higher authorities who rely on paperless communication,” says Tenzing.

During monsoon, the area is prone to landslides at multiple points, blocking connectivity for a day or two.

Also read: Why Yangtse in Tawang sector is the sore point China keeps returning to

Long way to go

Zemithang is still more connected and developed when compared to the charming hilltop village of Chayang Tajo in East Kameng district. It is only 81 km from the district headquarters, Seppa. But the broken roads, made worse by continuous rainfall, make what would have been hardly a two-hour journey an arduous 6-7 hour ride.

East Kameng district with its mountain ridges, deep gorges and waterfalls, surrounded by deciduous forests and bamboo groves is far removed from most of India. The Kameng river, a tributary of the mighty Brahmaputra, swiftly flows through, connecting lives and habitats.

The region is home to the Nyishi community, the largest ethnic group in Arunachal Pradesh spread across eight districts, besides other tribes like Miji and Sulung (Puroik). Chayang Tajo is dominated by the Nyishi clan and a small percentage of Puroik.

Few vehicles could be seen plying on the roads through remote villages leading to Chayang Tajo. A bevy of farm animals, chicken and Muscovy ducks waddle outside homesteads.

“We want roads. The rich sit in Itanagar and have less to worry about. The government pumps in money that is never rightfully utilised. It is because of corruption that we have such poor roads,” says 60-year-old Tame Yangfo, businessman and a former Zila Panchayat leader.

Yangfo says the road to his village was built during the Emergency in 1975.

“This road has existed since Indira Gandhi’s time. She made it during the Emergency, involving all villagers. Monsoon is the hardest time of the year. It is impossible for light vehicles to shuttle along these roads,” he adds.

Atung Yangfo, who runs a fair-price shop in the area is unaware of the Vibrant Villages Programme, but hopes that the road from Seppa to Chayang Tajo would be developed under this project.

“We don’t know if it would be a vibrant village. But we want the road to be fixed,” says the 19-year-old.

Villagers now have 4G network connection,but want more internet service providers. And their list of demands has reached the administration.

“We are submitting the plans for each village after due consultation with the stakeholders. In the coming days, these villages will be welcoming tourists from other parts of the country, and become truly Atmanirbhar,” says Deputy Commissioner of East Kameng district Sachin Rana.

Also read: How Arunachal is front & centre in Modi govt’s massive border infra push to counter China

Electricity, connectivity and roads

Around 28km from Chayang Tajo, local people at Laching Bagang are hoping that their village will be developed into a ‘Smart Village’ with basic facilities including electricity and network connectivity. Currently, the village has 21 households, with dwellings built under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana.

“Some of us have mobile phones, but there is no cell tower in or around our location. The phones are useless,” says Mara Bagang, a resident of the village.

The men in the village are impeccably dressed in ethnic attire, complete with the traditional Byopa, a cane headgear, adorned with a wooden Hornbill beak. The women come together to prepare two varieties of Rangbang, a traditional sticky dish made with Sago palm flour or rice flour, served with meat and local wine called Oppoh.

“Our ancestors did not know how to read or write. They used to do farming and jungle rats would destroy the crops. Now, we get free ration from the Modi government,” says resident Taye Bagang. For them the Indian Army is a symbol of safety and protection, and a possible source of employment.

Many of us could not even clear the tenth standard, but we wish for our children to join the military–Taye Bagang

“The China border is far from our village, and even if we were to live close to the border, when the Indian Army is here, we have no fear.” Chayang Tajo is located at an aerial distance of around 50-60km from the India-China border. “Our only fear is wild animals preying on the Mithuns. Many of us could not even clear the tenth standard, but we wish for our children to join the military,” he adds.

However, there is bitterness among villagers towards the district officials. “The local legislator and district officials do not visit us. We need medical services, electricity and connectivity,” says Taye Bagang, the Gaonburah or village head of Laching Bagang.

There are 16 PHCs in Chayang Tajo sub-division, but local people generally prefer to visit Seppa, Itanagar or even Tezpur for better medical facilities. And it’s expensive. Because of the lack of proper roads, villagers land up paying anywhere between Rs 500-900 for a seat in a Tata Sumo to go to town.

About 17 km away, Jayang Bagang has also been nominated to become a Vibrant Village. It looks prosperous with its paddy fields and maize farms, fish ponds and cattle. However, the Gaonburah, Kanya Bagang, feels otherwise. He says the pigs, goats and chicken in the village have perished due to unknown diseases. He wants the government to set up a veterinary unit before everything else.

For 60-year-old Tena Bagang, Jayang Bagang is a “neglected basti” with no network connectivity, irregular power supply and narrow roads. Since November 2021, Jayang Bagang and the adjoining villages have been drawing power from the mini-hydel unit with a generating capacity of 100W, which is not enough.

“The road should be widened and public transport should be introduced. Network towers should be built,” says Tena, dressed in traditional Nyishi attire, and carrying a satchel made of bear skin and an old Dao (sword).

Tena’s wife, 40-year-old Yayam Bagang has been learning to weave plastic bags and baskets since last year. While the bags are priced at Rs 600-800, the baskets cost Rs 2,000 or more. She sells the finished products at Seppa, Chayang Tajo town and Itanagar markets. Their second son aspires to join the Army.

In the past, villagers would mostly cook bamboo shoot and Rangbang.

“We used to kill rats for food, or any wild animal. Families used to be bigger then, and there were more mouths to feed. At least five families would live in one household. Things gradually changed since the eighties. Many have since migrated to towns and cities, many others died,” says Kanya who used to be a Zila Panchayat Member around that time. Now, he earns Rs 1,500 per month as the Gaonburah.

Everyone in the region is curious about the tourists who may visit them soon. But many are aware that development and tourism can extract a heavy price in the form of environmental degradation. The people of Zemithang and Chayang Tajo have urged the government to ensure that their ecosystem is not destroyed.

“Zemithang is a small place and we have to keep it clean. Tourists should be sensitised not to throw garbage, to respect wildlife, our mountains and trees,” says Pemba Tsering Romo, local volunteer for World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

With modernisation, villagers have become more aware of the need for conservation of biodiversity and maintaining ecological balance.

“There may be tourism avenues here, but we have never seen tourists before,” says Tena.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)