New Delhi: On a lazy afternoon at Mumbai’s Juhu beach, two tattooed teenage boys suddenly broke into somersaults. A crowd gathered, cheering and clapping. The boys kept flipping till they reached the edge of the sea.

The boys were breakdancing, or breaking, but their impressive display was not just an artistic performance. Breaking is now an Olympic sport, set to debut in Paris 2024, on the same footing as wrestling, shooting, or weightlifting.

For India’s young breakdancers — or B-boys and B-girls — what started as a rebellion against parental and societal pressures, is evolving into a promising career choice in sports. The acrobatic techniques many of them honed on beaches, sidewalks, and parks could help them win medals for India.

Indian breakers are already carving out an international reputation. Some come from the slums of Mumbai, others from small towns in the hinterlands. As is the norm in breaking culture, they all take on alternate dance personas on stage, complete with funky nicknames.

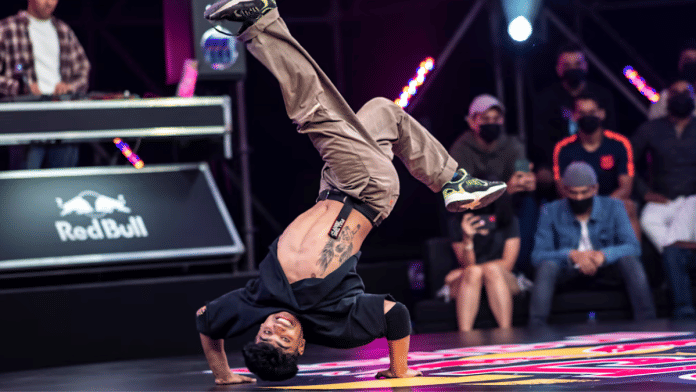

At this year’s Red Bull BC One Cypher India— a qualifier for the top global competition for breakdancing — 16 B-boys and 8 B-girls broke out their best moves in one-on-one face-offs. The winners were Goutam Kaulsee aka Ginni, from Kurukshetra, and Simran Ranga, aka Glib, from Jaipur. They have qualified for the Red Bull BC One world finals at Paris’s Roland-Garros Stadium in October.

Last year, B-boy Eshwar Tiwari aka Wild Child represented India at the world finals in New York. Then there is Arif Chaudhary aka Flying Machine, a three-time BC One Cypher India champion, and Ramesh Yadav aka Tornado, the 2019 winner, who fought his family to pursue his passion. All three are from Mumbai.

The top B-girls include Siddhi Tambe, aka BarB, from Mumbai, who reached the finals in New York last year, and Johanna Rodrigues, aka B-Girl Jo, from Bengaluru, a two-time Cypher champion who transitioned from Bharatnatyam to breaking.

But while Red Bull sponsors those who qualify for the BC One world finals, participating in events to rank for the Olympics is more challenging. The Breakdance Federation of India, only two years old, is still awaiting recognition from the government.

On 23 February, six B-boys and B-girls represented India in Japan’s Breaking for Gold (BFG) competition to earn ranking points for the Olympics qualifier rounds.

B-Girl Jo ranked 50th here — the best among all Indian participants. Arif aka Flying Machine got the 59th rank. But in the BFG in Brazil this April, only two Indian breakers competed.

A lack of finances and institutional support are major hurdles, breakers say.

“We grew up in slums. People living in high rises would look down on us. But times have changed. We are the ones who can bring an Olympic medal for the country,” says top breaker Eshwar Tiwari.

He hasn’t participated in any of the BFG events because of a shortage of funds. He says many others are in the same boat.

“We are looking for a sponsor to support us. We have to do all the work ourselves, from fulfilling our dreams to going abroad,” he says. “But when we come back victorious, that victory will be for the country.”

Also read: WPL historic but not without these commentators, umpires—’Sachin on microphone’, fun umpiring

Art, sport, passion

Is breaking a sport or an art? It’s perhaps a bit of both, with roots in the US hip-hop culture of the 1970s. Back then it was a form of escape and artistic transcendence for impoverished youth living in the gritty suburbs of New York. With no formalities, minimal rules, and no equipment, it was a platform for creative expression. Even gravity couldn’t get in the way.

Today, breaking is mainstream and there’s an industry around it. There are sponsored contests, training programmes, even specialised shoes. At the competitive level, it’s more about gymnastic prowess than counter-culture style. The intricate footwork, freezes, and dynamic spins were an art, now they are a bit of a science.

But for many Indian stars, breaking started as an escape from the margins, much like the original breakers of the 1970s. Many of them are self-taught.

Their first coach was the computer screen at the local cyber cafe. They figured out most of their own moves, drawing inspiration from dancers seen on TV or from their friends. When they got good enough to compete and travel for competitions abroad, they learned more from their fellow competitors from around the world — and then added their own spin.

Eshwar Tiwari’s stage name is Wild Child. In 2019, one of his moves, dubbed the “wild spin”, went viral after he performed it during a competition at the Breezer Vivid Shuffle, India’s homegrown hip-hop festival.

B-boy David ‘Kid David’ Shreibman, known for his appearance in the 2011 musical Footloose, was judging the event.

“When I performed the move, Kid David got up from his seat and cheered. The crowd went crazy,” Eshwar recalls.

Eshwar says he created the ‘wild spin’, his signature move, by accident.

“One day, while training with my friends and crew, I started doing a shoulder spin. Accidentally, my hand got stuck in a position I had never tried before. After that, I took it as my own style and practised it for over two months,” he says. “I tried this move at the BC One Cypher India 2021.” He won the contest that year.

Arif ‘Flying Machine’ Chaudhary, who speaks with equal ease in Mumbai slang and an American twang, was also self-taught.

He says he absorbed his skills from online tutorials on YouTube and Hollywood dance movies like Turn It Loose, Break Out, and You Got Served.

Now 25, he says he started dancing on the streets at the age of 10.

“My breaking has been trained in the streets and parks of Mumbai. I have never taken formal training,” he adds.

Today, he trains others and is even in the process of starting a dance institute. He has won numerous competitions in India and has represented the country abroad too.

He participated in the Breaking Boundaries competition in Austria in 2018, winning his first international jam. He also B-boyed at championships in Netherlands, Slovakia, and Japan, among others.

But behind the triumphant moments and passion are also some stories of hardship and struggle against family disapproval.

Also read: WPL changing cricket crowd culture. Kids in stands scream Jemimah, men now say ‘batswoman’

Poverty, rebellion, heartbreak

Arif’s family is proud of his achievements today, but that wasn’t always the case. When he was growing up in Mumbai’s Jogeshwari, his parents worried about his love of dancing. In his Muslim community, dancing is considered haraam. His father, a contractor, also wanted him to focus on his studies.

“I was scolded a lot in my childhood for dancing. Everyone was worried about my career but I was only worried about my dancing,” he says.

Arif would often hide his dancing pursuits from his father, who’d even beat him if he discovered his son busting moves instead of poring over textbooks. He was good at studies, but once he started excelling in dance, he just couldn’t finish his graduation.

“My mother always supported me. When I came back victorious for the first time, my father also supported me a lot,” he says

Ramesh ‘Tornado’ Yadav has been breakdancing since the age of 10.

“Breaking is being launched in the Olympics in 2024, but we have been breaking our bones for 15 years for it,” he laughs.

His passion for breakdancing has not been easy either. When there was no support from the family, he left the house and went on to live alone.

Ramesh’s passion for dance was awakened by seeing Sagar, a dancer in the same slum neighborhood, Mankhur Gawandi in Mumbai. Sagar used to teach dance to the local children and hold informal one-on-one contests.

When Ramesh first started breaking, he didn’t even know it. He thought he was performing action stunts.

“A brother from the slum told me that I dance well. I did not know that there is competition in this dance and battles are fought,” he says.

In 2019, Ramesh won the Red Bull BC One Cypher India. He has also travelled abroad for dance-offs with the help of sponsorships. He dreams of making it to Paris 2024, but is worried about being able to raise enough money.

Eshwar Tiwari’s story is not very different from that of Ramesh and Arif. He started dancing in 2012 when he was 14 years old. He dropped out of school soon afterward.

“At that time, I didn’t know what I was doing. “I just knew that when I dance, it changes my world,” he says.

Eshwar’s family also did not support him— except for his mother. “My mother loves me a lot, she believes in me. Today you are talking to me just because of her sacrifices and belief,” he says.

Eshwar’s father passed away in 2020, but he says other family members who disapproved of his dancing have now come around. His grandmother loves it when he speaks in English, which he picked up on trips abroad.

“Earlier, I used to practise secretly, he says. “Now my family members are proud of me.”

The B-girls

Mumbai’s Siddhi ‘BarB Girl’ Tambe, one of India’s best-known breakers, won the BC One India title in 2021 and went on to compete in the world finals.

Her journey began with learning Bollywood dance, and her instructor convinced her to go for breaking, she says.

She is hoping to qualify for the 2024 Olympics, but finances are an issue for her too. Her mother is an anganwadi teacher and her father is a hospital ward assistant. Money is tight.

Siddhi, who is pursuing her second year of graduation, says her family is divided about her dancing. Her mother wants her to continue, but her father has reservations.

As a result, she has taken a middle path — for her mother, she is pursuing dancing, but for her father, she is not letting go of academics either.

“I am good at studies. I want to become a scientist, but I don’t want to leave my dance, so I am pursuing botany and chemistry. I also want to do an MSc,” Siddhi says.

Another Olympics aspirant, Bengaluru’s Johanna ‘B-Girl Jo’ Rodrigues has had a smoother transition into becoming a full-time dancer than many others.

Her mother is a classical singer and did not object when her daughter chose to pursue her unconventional calling. Johanna discontinued her education after Class 12 and her life revolves around breaking and other types of dance, she says.

She pours most of her earnings into working with trainers, ensuring optimal nutrition, and upping her game. “I wish the government would support us too,” she says.

A struggle to qualify

The Paris 2024 will take place in July-August next year, but time is running out to rack up enough points to even reach the final Olympics Qualifier Series.

The rankings of breakers depend on how they place at various international competitions, such as the Breaking for Gold (BFG) series. So far, only a handful have been able to give it a shot.

At the BFG in Japan’s Kitakyushu, a team of six competed. Among the three B-Boys, Arif secured the 59th position, followed by Ramesh, and Suraj Raut (‘B-boy Suraj’) at the 62nd and 91st spots, respectively.

Among the B-girls, Johanna achieved the highest Indian ranking at 50th position, Sushma Satish Aithal (‘B-girl Sushma’) landed at 64th place, and Siddhi Tambe finished 76th.

At the BFG in Brazil’s Rio de Janeiro April, the number of participants dwindled to just two. Only Suryadharshan ‘Crazy Bright’ Bagiyaraj and Sushma represented India, clinching the 68th and 51st positions in their respective categories.

Biswajit Mohanty, the secretary of the fledgling Breakdance Federation of India (BDFI), tells ThePrint that he and other representatives had met Union sports minister Anurag Thakur in March, ahead of the Brazil contest.

They had presented a plea for funding to support athlete training and preparation ahead of the Olympics, but Mohanty says they are yet to receive a definitive response. The BDFI is not yet recognised by the government.

Even managing to send six breakers to Japan was a struggle. “We just don’t have enough money. A trip costs about Rs 12 lakh per person. We were not able to even send a coach along with our athletes,” he says.

“We have also approached the Indian Olympic Association for funds. We tried to meet its president PT Usha, but were not able to. We have left a letter for her,” he adds.

In this backdrop, most Indian breakers are keeping their fingers crossed for individual sponsorships to participate in competitions that will help them qualify for the Olympics.

A total of 32 breakers— 16 B-boys and 16 b-girls, will compete for the first-ever Olympic medals in breaking.

The qualification system is somewhat intricate. But in essence, qualifying depends on how an athlete places on the World DanceSport Federation (WDSF) Breaking World Ranking. Points can be earned by participating in WDSF Breaking events and other selected competitions. The top-ranked athletes will qualify for the Olympics. There will also be a final qualification series where athletes can earn a spot at the Olympics.

Preparing for the cold, ‘training 7-8 hours daily’

Indian breakdancers face challenges beyond their families and sponsorship, such as adapting to foreign weather conditions and food.

“Europe, Netherlands, Japan are all very cold countries… we have to face a lot of difficulty in warming up our body,” says Ramesh ‘Tornado’ Yadav.

All the breakers who the Print spoke to say that training hard is essential for breakdancing. All said they practise for at least four to five hours every day, apart from working out at the gym for another few hours.

Ramesh currently teaches children for four hours and dedicates 7-8 hours to practice. Johanna says yoga also helps her maintain her edge.

In the run-up to the Olympics, they are all practicing in the lowest AC temperatures possible so they can acclimatise easily if they have to compete in cold conditions.

Sharing his memories of competing in the Netherlands some six-seven years ago, Ramesh says he felt shaken by the language barrier and unfamiliar food.

“I went to a gurudwara there and ate dal-chawal,” he says. “I could not speak English properly. Since then, especially after he was crowned as the BC One Cypher India champion in 2019, his confidence has grown.

He says he was starstruck at his first international competition, but now he feels like a part of the top-level global circuit.

“I used to get nervous when I saw people whose videos I learned breakdancing from,” he says. “Now the world’s best breakdancers are my friends.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)