New Delhi: Mumbai-based lawyer and gynaecologist Dr Nikhil Datar kept seeing women walking in for late-term abortions. This was in 2008, when the upper limit for abortion was 20 weeks of gestation. Determined to help his patients who had discovered their pregnant status late and were beyond the legal framework to seek a safe abortion, Datar approached the Bombay High Court to seek permission to terminate one of his patient’s pregnancies. The abortion was denied. But in 2016, he went to court again. This time, a favourable judgement carved a new path for women to approach the courts for abortions beyond 20 weeks.

Earlier this month, like many of his patients, a 26-week pregnant woman approached the Supreme Court. And her case has brought a new perspective to the abortion debate. What was long restricted to legal and medical procedures in India has, perhaps for the first time, taken a US-style detour to delve into the questions of heartbeat, life and choice.

Unlike the US, Indian women did not have to go through bruising debates, gruelling public protests, or fight battles over religion and morality to get access to safe abortion. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act was carved out as an exception to the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises abortion.

“India is in a better condition as far as access to abortion is concerned. We have access to abortion as a law and not a judgment which can be overturned at any time. We don’t have the religious and conscientious objection problems, which the West is facing. Our problem is about the health system itself. Whether it exists or not, or if it exists, it is not up to mark,” said Anubha Rastogi, a Mumbai-based lawyer who works on reproductive justice.

Also Read: India & US have similar levels of support for legal abortion, finds Pew survey

Morality debate

Yet, in the Supreme Court, a plethora of moral and ethical questions came up.

The case has stirred the community of lawyers, activists and doctors into reinventing and recycling the American debate about how much control pregnant women in India have over their bodies and whether pro-life, pro-choice arguments hold water in the Indian courts.

“We have not been talking about foetal viability at all in India. It’s a very US concept. They humanise the foetus. Whereas we say the foetus becomes a child only after birth. How can we be pro-life if we disregard the wishes of a woman who is saying that she needs an abortion?” asks Debanjana Choudhuri, director, programs and partnerships, Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India, a non-profit.

The case of the 26-week pregnant woman was not extraordinary. She said in the court that her contraception failed and since she was nursing her second child, a one-year-old infant, she mistook her lack of menstruation as lactational amenorrhea, a condition where nursing mothers do not menstruate and hence, cannot conceive. She realised that she was 24 weeks pregnant when she approached a doctor for dizziness, abdominal pain and nausea.

She immediately pleaded in the SC that she is suffering from postpartum depression and her mental and financial condition does not permit her to bring another child into the world.

But after the first hearing on 9 October where she was permitted to abort, the focus shifted from her vulnerable condition to the healthy foetus growing inside her.

The court observed that the foetus has a strong possibility of survival, medically called ‘foetal viability’. If aborted, the doctors will have to first “stop the heartbeat” of the foetus in the womb. If this procedure is skipped, the baby will be born preterm, will have to spend a long time in intensive care, and may develop physical and mental disabilities, the SC noted based on the advice of a medical board at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

We have access to abortion as a law and not a judgment which can be overturned at any time… Our problem is about the health system itself.

– Anubha Rastogi, lawyer

One of the two judges overturned her decision after the update from AIIMS, saying her “judicial conscience” prevents her from allowing the woman to abort. A week later, on 16 October, a three-judge bench upheld the overturned decision and did not allow the woman to abort.

The verdict changed the woman’s fate.

Also Read: Raped by ‘uncle’, a 13-yr-old mother battles stigma — ‘if we keep that child, who’ll marry her?’

Stopping the heart

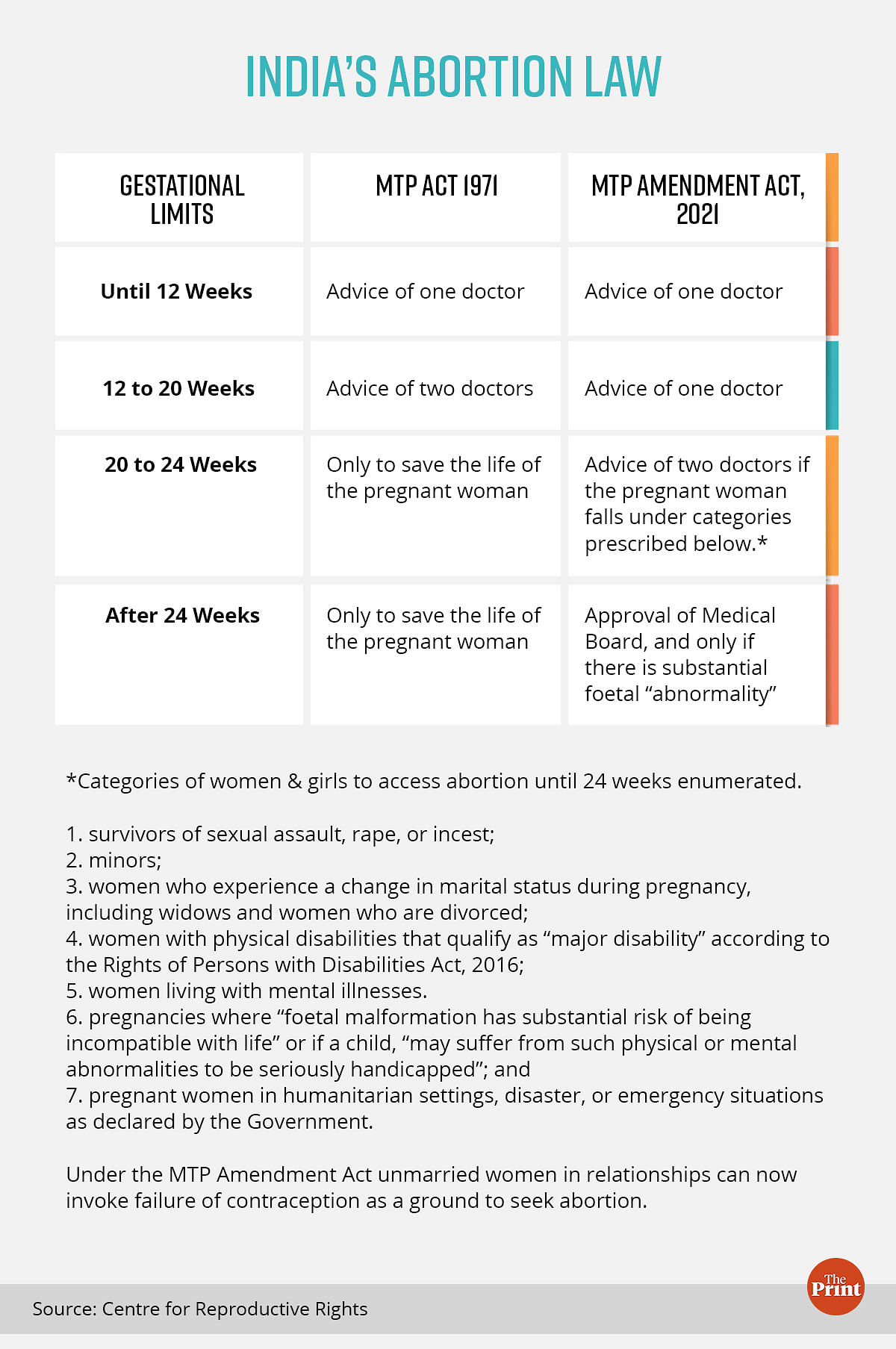

Last year, around this time, the advocates of safe abortion in India were jumping with joy. The SC had permitted abortion at over 23 weeks for an unmarried woman. The upper limit for aborting as per the Indian abortion law, after the 2021 amendments, is up to 24 weeks. But beyond 20 weeks, abortion is allowed only for certain cases, for instance, rape victims or women in disasters.

Though the law allows widowed or divorced women to abort after 20 weeks if there is a change in their marital status during their pregnancies, it is silent about unmarried women. In the case of the unmarried woman, the court allowed it after her partner refused to marry her.

But the same court denied abortion to the 26-week pregnant woman despite her desperate pleadings. While there was debate around whether her mental health can be a ground for granting her permission to abort, the focus shifted to the unborn baby’s beating heart in the courtroom.

How can we be pro-life if we disregard the wishes of a woman who is saying that she needs an abortion?

– Debanjana Choudhuri, Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India

When the woman reached AIIMS for abortion on 10 October, one of the doctors wrote to the SC seeking clarity on whether the heart of a healthy foetus growing inside the woman be stopped or not.

“If feticide is not performed, this is not a termination, but a preterm delivery where the baby born will be provided treatment and care,” wrote the doctor in an email to the government’s counsel. It added that the heart of the foetus is stopped in cases where the foetus has “abnormal development”, but is often not done in a “normal” foetus.

While the email shook the judges and made them rethink their decision, the doctors ThePrint spoke to explain that this procedure is common practice.

“After 24 to 26 weeks of gestation, most foetuses that have a heartbeat will not survive the process of abortion. But an occasional foetus will be born with a heartbeat. To avoid this difficult situation for the doctors as well as the parents, a potassium chloride (KCL) injection is recommended into the foetal heart to stop it before doing the abortion,” said Dr Jaydeep Tank, president-elect, Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Society of India (FOGSI).

It is a recommended practice by The Royal College, UK and the World Health Organisation (WHO). It is also prescribed in the Indian government’s guidelines to the medical board.

We have not been talking about foetal viability at all in India. It’s a very US concept. They humanise the foetus. Whereas we say the foetus becomes a child only after birth.

— Debanjana Choudhuri, Foundation for Reproductive Health Services India

The procedure of stopping the heart is performed in cases of other pregnancies, such as in sexual assault cases, which go beyond 24 weeks.

“The situation that the SC faced is not something new. The injection is given in cases where the foetus has abnormalities and the abortion happens after 24 weeks. It’s also done when the pregnancy is a result of rape or where the victim is a minor. If the foetus comes out alive, it is the state’s responsibility,” said Rastogi.

In the case of the 26-week pregnant woman, the AIIMS doctors should have informed the SC about the use of the foetal injection in their first report itself which was filed on 6 October, added Rastogi.

Dr Datar, meanwhile, said that raising an issue of the foetus’ heartbeat was uncalled for as the heartbeat of the foetus can be heard at seven weeks as well.

“When the heartbeat is heard and that is interpreted as a life whose sanctity has to be preserved, then you cannot terminate a pregnancy at even seven weeks,” he said. He added that aborting at an earlier stage of pregnancy also means stopping the heart and extinguishing a life.

In cases where the court directs the doctors to abort a pregnancy post 24 weeks, the doctors have to inform the court that they are using the injection to stop the foetal heart, said Dr Tank.

“The medical board is fully qualified to prescribe whether a KCL injection should be given or not. The court only has to give permission. It doesn’t have to tell the doctor how to do the abortion,” he added.

Also Read: India and US went pro-choice around the same time. Only one strengthened its abortion laws

Rights of women vs the rights of the foetus

Instead of accepting these medical intricacies the case in the top court swung between the rights of the woman and the rights of her “unborn child”.

“Throughout my career, I have not come across a single woman who comes for termination of pregnancy, that too at a higher gestation, just for fun or for the sake of establishing her right or proving a point,” said Dr Datar.

While the clock was ticking for the 26-week pregnant woman, CJI DY Chandrachud emphasised that India’s abortion law is “far ahead of other countries” and is “liberal and pro-choice”. “We will not have a Roe vs Wade situation here,” he said, as reported by The Indian Express.

But the reproductive rights activists ThePrint spoke to, disagree. Slipping in “foetal viability” in hearing abortion cases is a new turn in India.

The rights of the foetus often come up in cases of sex determination, but it is uncommon in cases of abortion, said reproductive rights activists and lawyers.

Yet, the healthy status of the unwanted foetus became one of the grounds for the SC rethinking its decision to allow the woman to abort.

Throughout my career, I have not come across a single woman who comes for termination of pregnancy, that too at a higher gestation, just for fun or for the sake of establishing her right or proving a point

-Dr Nikhil Datar, lawyer and gynaecologist

Additional Solicitor General (ASG) Aishwarya Bhati, who appeared for the central government, said in the courtroom that the 2021 amendment to the abortion law balances pro-life and pro-choice. The debate in the case is not pro-life or pro-choice, it is whether pro-choice can go to the extent of extinguishing life, she said, as reported in The Indian Express.

Every tactic in the book was used to persuade the 26-week pregnant woman to continue her pregnancy. The ASG tried to convince the woman to wait a few more weeks and let the foetus develop fully, but the woman was undeterred.

“I have made a willful and conscious decision to medically terminate my pregnancy. I do not want to keep the baby even if it survives,” the woman wrote in an affidavit.

But the ASG continued to argue that some countries have given the status of “protected citizens” to unborn children. The abortion law, she added, gives “untrammelled discretion to the woman within the period of time that is provided”, reported The Indian Express.

The opinion was divided on where to draw the line when it comes to abortion. Should the heart of a healthy foetus be stopped? And does the woman’s mental health and financial status count as sound ground for letting her abort beyond what is permitted in the law?

“It depends how you define life. When does life come into being?… Life which is viable outside the womb, or does life mean something even within the womb too…,” Chandrachud said.

The experts also say that the arguments in this case reflect how abortion is being looked at from a moralistic lens.

“Had this been a pregnancy of a 13-year-old child, and not of a married woman, then would the court be bothered about the life of the teenager or the right of her foetus,” asked Dr Datar.

Also Read: 78% of Indian abortions are outside clinics, even with a good law

The case and the law

The results of the 2021 amendment to India’s abortion law were almost instant.

The number of cases handled by Dr Datar shows that between 2016 and 2021, he filed 324 cases for abortion of pregnancies between 20 and 24 weeks. This number dropped to just 10-12 cases in the last two years.

Besides, a report analysing the cases in the courts by Pratigya Campaign, a group of organisations and individuals advocating reproductive rights, shows that out of 243 cases filed across 14 high courts between May 2019 to August 2020, 74 per cent were filed post the 20-week gestation period allowed in the law then.

The 2021 amendments gave a much-needed breather to the abortion law. But women don’t always realise they’re pregnant with an unwanted foetus within the legally mandated timeframe for abortion. The 26-week pregnant woman’s is one such case.

“Lactational amenorrhea is not something which is uncommon. It is not implausible that someone would have postpartum depression and lactation amenorrhea resulting in missing that she’s pregnant and thereby coming late for an abortion,” said Dr Tank.

But can this case push the limits of the law to include mental illnesses as a ground to end the life of a healthy foetus?

While the first judgement on 9 October was sensitive to the woman’s delicate mental and financial condition, the subsequent hearings put her on the line. On 13 October, the SC asked AIIMS to conduct further checks on her mental and physical condition and if the medicines she is taking for her mental condition would affect her foetus.

Had this been a pregnancy of a 13-year-old child, and not of a married woman, then would the court be bothered about the life of the teenager or the right of her foetus

–Dr Nikhil Datar, lawyer and gynaecologist

It concluded that the woman’s medical condition can be managed by drugs and in case her condition worsens, “she may be admitted and treated”. The woman’s lawyer appealed that she is suicidal and has a tendency to harm her children, reported The Indian Express . But these found no consideration in the final verdict.

Her situation was viewed from a narrow prism of the MTP Act and how much leeway it gives to women.

“This case opens a huge conversation about mental health. It shows how inept we are and how there is a lack of standardisation in how the courts interpret the law. The law states that if the status of the woman changes, she can abort. Here her situation changed. She was suffering from postpartum depression. Why did the case even go to the Supreme Court?” said Choudhuri.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)