Agra/Jhansi: The city of the Taj Mahal is now one of India’s top three Smart Cities. And the biggest change is that a team of two dozen officials now monitors potholes, stray cattle, and traffic on a real-time dashboard from the Agra Smart City office in the Nagar Nigam.

“Look at this,” said one official, as he pointed out a feed of a man jumping a traffic light on one of the two computers on his desk. Another employee patiently explained the time needed to fill potholes to a concerned citizen over the phone.

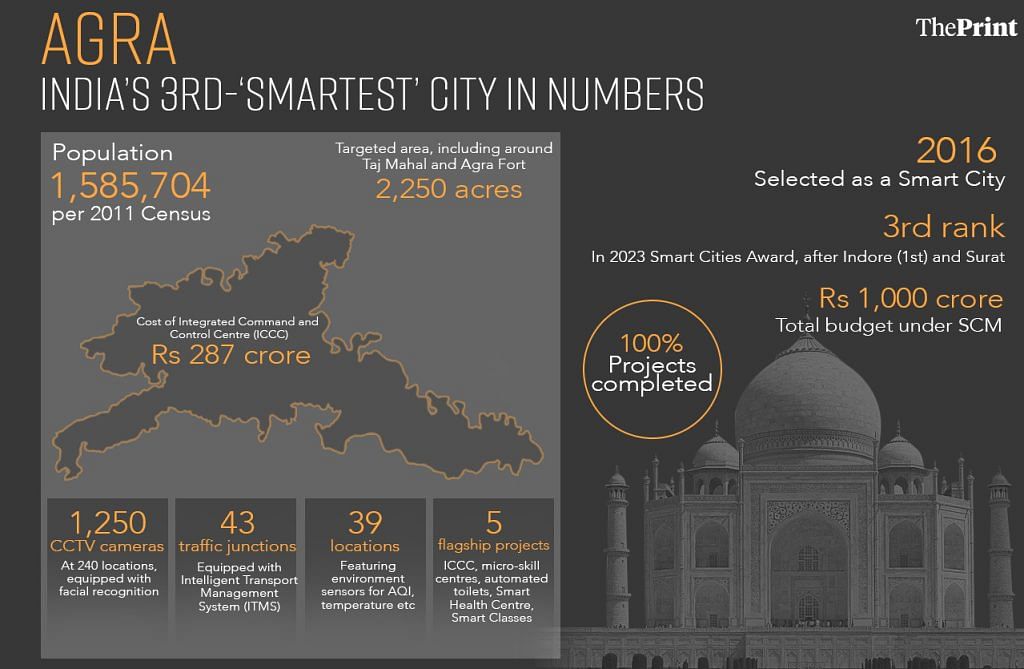

Dominated by a large LED screen, this is part of Agra Smart City’s 24/7 Integrated Command and Control Centre (ICCC). It started full operations in 2021 at a cost of Rs 287 crore, consuming over a quarter of the total Rs 1,000 crore Smart City budget. Here, young employees field calls from citizens about issues such as water supply and bumpy roads, logging them for local authorities to address. Occasionally, they catch traffic violators on camera feeds and initiate e-challans.

Nearly 10 years after the launch of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ambitious flagship Smart Cities programme, it has largely devolved into an urban municipal governance project tackling 20th-century issues like garbage collection, sewage disposal, and drinking water. Essentially, it is doing what the UPA-era Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) left unfinished.

In Agra, the rest of the Smart Cities money has been spent on beautification efforts—Radha-Krishna murals, park regreening, red sandstone signages—as well as sensor-activated “self-cleaning” toilets, skill development centres, and “smart” health centres that provide services like lab tests and dental care at subsidised costs. While Urban Development Minister Hardeep Singh Puri has described the Smart Cities Mission as “a revolution in urban governance”, none of these initiatives are particularly high-tech or groundbreaking.

And yet, in the annual national Smart City rankings by the Ministry of Urban and Housing Affairs last year, Agra ranked third, following Surat and Indore.

“We focused more on basic facilities like roads, sewage, and infrastructure projects because it is more important to develop the basic things before building a technology-based city,” said Arun Kumar, general manager (projects), Agra Smart City Limited (ASCL). “Right now, our target is to make the completed projects sustainable and revenue generative.”

The effectiveness of the Smart Cities Mission has been subject to debate, with some critics arguing it deepens existing inequalities within and between cities.

Also Read: Hyderabad is having a raging demolish-restore debate over Osmania. Everyone has an opinion

Big vision, modest reality

Fatehabad Road, a hub of hotels in Agra, is a prime example of polishing and buffing under the Smart Cities Mission (SCM). Fancy lights, hanging flower pots, metro pillar paintings, vending zones, spiffy bus shelters, and functional “smart toilets”— all courtesy of the SCM—create a modern and inviting atmosphere.

Similarly, seven facades of heritage houses in the Daresi area have been spruced up at a cost of over half a crore, while municipal schools in Tajganj have been upgraded with libraries, basketball and volleyball courts, RO water dispensers, and open gyms.

But just half a kilometre from the Taj Mahal, Kolhai Colony stands out for its broken roads and overflowing garbage heaps.

This patchy development reflects a common reality in many Smart City initiatives across India. Instead of a city-wide rollout, projects have been implemented in geographically concentrated areas. Large chunks of SCM budgets have also been allocated toward initiatives typically managed by municipal bodies.

Agra, for one, has adopted an area-based development approach, with the Smart Cities Mission covering 2,250 acres across only nine of its 90 wards.

“A huge amount is required to develop any city, and the Smart City Fund could only be used to develop a specific area where we tried to fill the basic service gap,” said Saurabh Agrawal, chief data officer for Agra Smart City.

But back in its 2014 manifesto, the BJP envisioned smart cities as grand urban digital utopias. It promised to build 100 new cities “enabled with the latest in technology and infrastructure” to improve quality of life and transform urban India into a beacon of efficiency, speed, and scale.

“A Smart City means a city which is two steps ahead of the basic necessities of a resident,” Modi proclaimed when launching the Smart Cities Mission in June 2015. “The city’s residents and leadership should decide how a city should grow. It should be bottom-up.”

At another event, then urban development minister Venkaiah Naidu said that if cities were built on riverbanks in the past and along highways in the present, they would soon be built “based on availability of optical fibre networks and next-generation infrastructure.”

However, the SCM guidelines did not provide a clear definition of a Smart City. “It means different things to different people,” the document said.

Putting LED lights and making drains on the street is not a technological intervention. Our cities’ infrastructure is still at the 1960s level. In the name of a smart city, a few e-governance websites and apps have been put in place

– Madhav Raman, urban planner & architect

The rhetoric about a bottom-up strategy also didn’t translate. To implement the mission, the Modi government created Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) registered under the Companies Act, as governing bodies for each city.

This approach excluded local elected representatives like MLAs, MPs, or councillors, handing the reins instead to officials like the Divisional Commissioner and the head of the municipal body. These SPVs report to the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

The tag of being ‘smart’ cannot be earned easily. The work in these 100 cities has evolved over time. Criticisms have mellowed and appreciations have flowed.

-Kunal Kumar, joint secretary & Smart Cities Mission director

While some cities and states, such as Mumbai and West Bengal, opted out due to concerns over central interference, many others competed to be selected as Smart Cities.

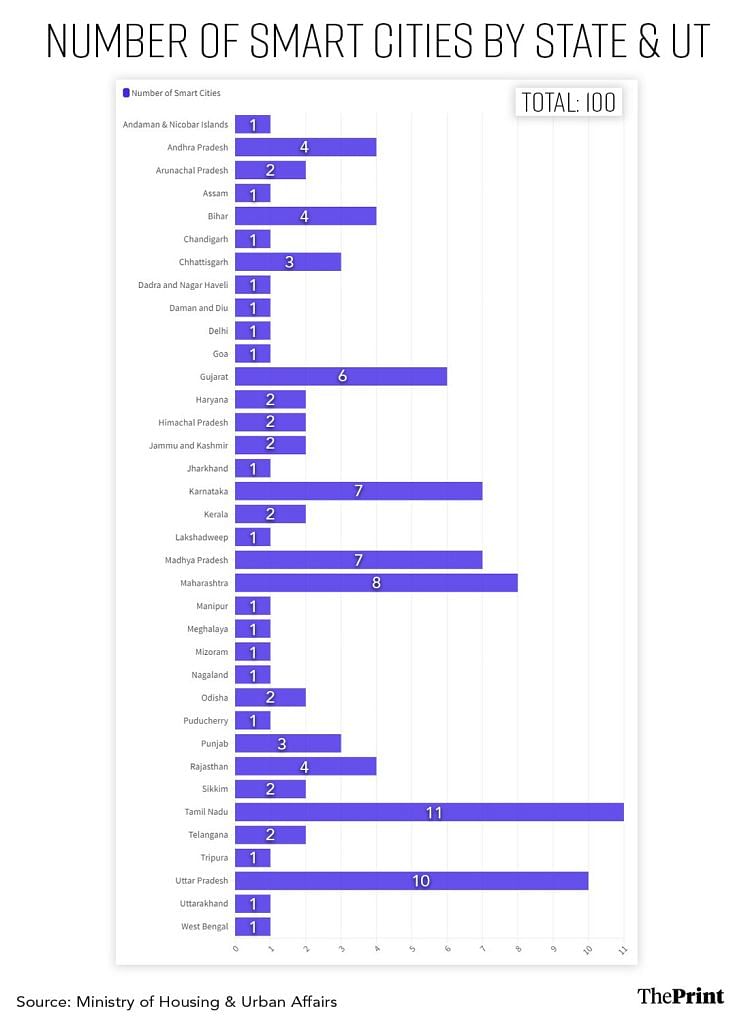

Finally, 100 cities were picked through four rounds of competition between 2016 and 2018, covering about 21 percent of the country’s population. All selected cities now have Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCC), dubbed their “brain and nerve centre” by the government.

For funding, the central government proposed to provide Rs 48,000 crore over five years. Each city was to get Rs 500 crore from the Centre, with states and urban local bodies to match this funding, adding up to Rs 1,000 crore. Cities were also expected to use other forms of financing such as PPPs and loans. Last year, the mission deadline was extended from June 2023 to June 2024.

In the SCM rankings released last year, Uttar Pradesh came third after Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu in the government’s national Smart City rankings. UP is home to 10 Smart Cities, of which Agra and Varanasi are both in the country’s top 5 for their performance on parameters like project completion and use of funds.

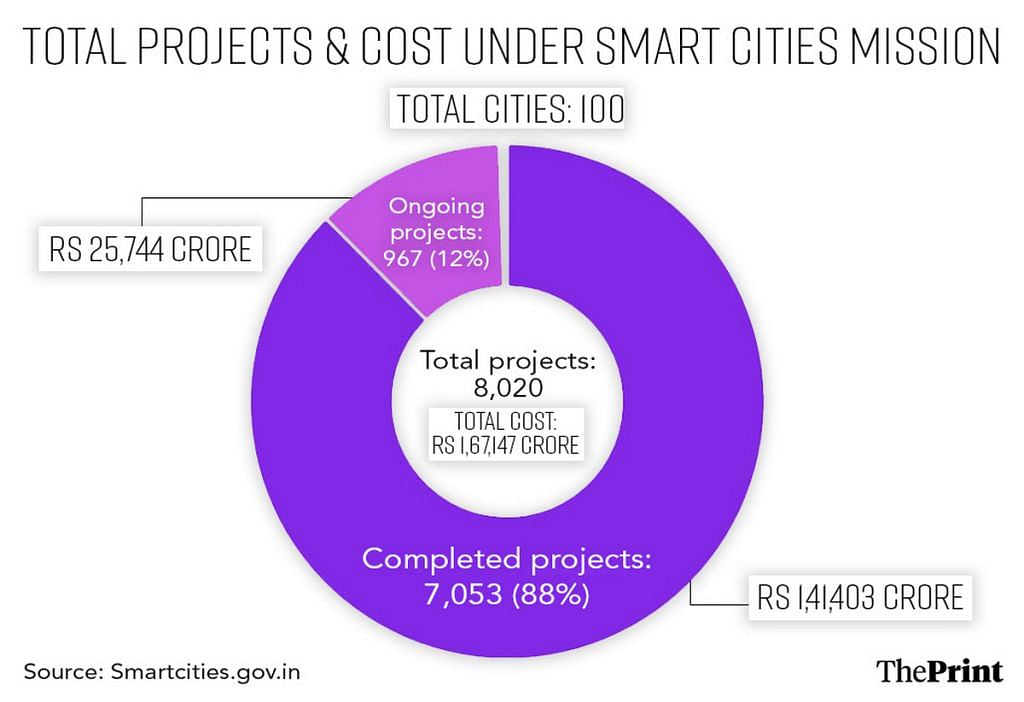

Nine years since its launch, the SCM website boasts that more than 80 percent of all projects have been completed. However, not everyone is impressed.

“The SCM was supposed to be a ‘lighthouse’ for other aspiring cities, but it has not even lit a lamp,” said urban planning expert Tikender Singh Panwar, a member of the Kerala Urban Commission and a former deputy mayor of Shimla. “The design of the scheme was too top-to-bottom and people had little participation.”

Officials, however, brush off such criticism.

“The tag of being ‘smart’ cannot be earned easily,” said Kunal Kumar, joint secretary and Smart Cities Mission director. “The work in these 100 cities has evolved over time. Criticisms have mellowed and appreciations have flowed.”

Another senior urban planning expert who was part of the PM’s task force on infrastructure argued that SPVs fast-track Smart City projects and allow for more flexibility, not less.

“Different cities decide according to their needs. Few things are mandatory,” he said, adding that the SCM works on a “convergence model” involving coordination with other government schemes such as Swachh Bharat and the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT).’

Modi, meanwhile, is no longer talking about the SCM. While he often mentioned Smart Cities before and during the 2014 elections, the subject was absent from his rhetoric when he was seeking his third term as PM in the 2024 polls.

The SCM is an example of a “toll-booth model of urbanisation”, according to Hussain Indorewala, who teaches at Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture, Mumbai.

Agra to Jhansi—art, tech, & paradoxes

Some Smart City budgets are being spent on programmes that have very little to do with technology. The centuries-old craft of zardozi making in Agra is one example.

In the rundown neighbourhood of Kolhai, women learn the intricacies of this gold thread work at a micro-skill development centre, established along with three others at a cumulative cost of Rs 2 crore under the Smart Cities Mission. The four centres teach seven skills, including marble inlay work, carpet weaving, and brush work, and have trained over 1,070 artisans over the last six years. Our art was on the verge of extinction but this mission revived it by connecting it to the market,” said Siraj Mohammad, a local marble inlay artisan. “The centre under the Smart City has changed our lives.”

While the skill centre received Smart City funding, the streets leading to the zardozi hub are beset with perennial problems of potholes and trash. Efforts to spruce up the city are more apparent closer to attractions like the Taj Mahal and Agra Fort, where murals of Radha-Krishna, animals, and birds were paid for by SCM funds.

“One should have a good feeling on entering any city, so the walls are painted,” said a senior official of ASCL, who didn’t want to be named. “This has been done in many cities and Agra also adopted it.”

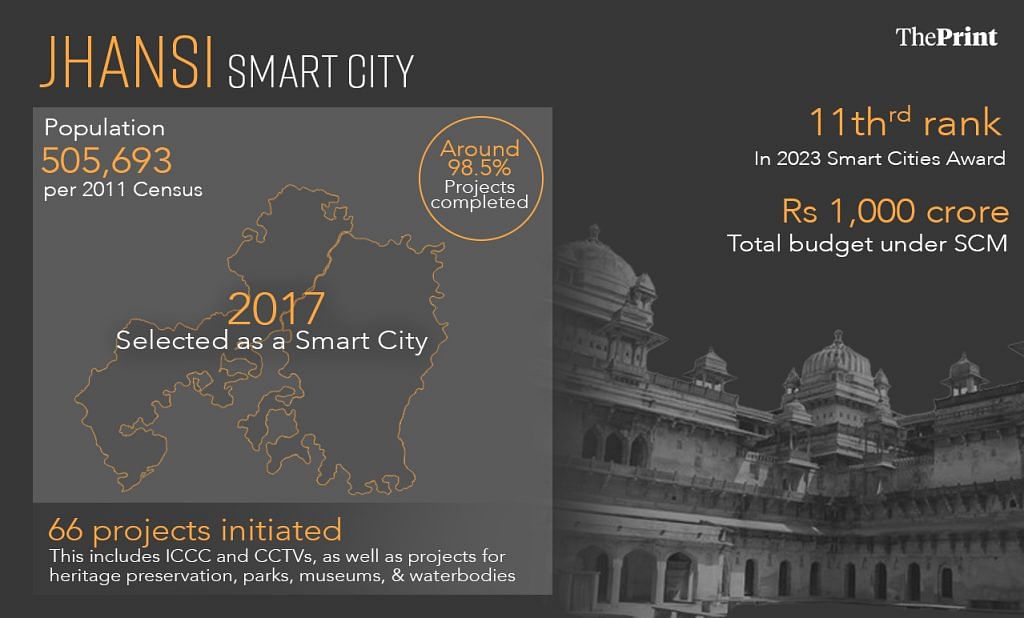

While Agra honed in on roads, MSME centres, and smart toilets in select areas, Jhansi, located some 225 km south, has had a somewhat different focus.

Figures shared by Jhansi SCM officials show that Rs 583 crore—over half of the funds—were allocated to developing museums, parks, water kiosks, multilevel parking, and reviving the city’s old water bodies such as Laxmi Tal and Atiya Tal, besides the standard ICCC and CCTV cameras. Most major projects are concentrated around the Jhansi Fort.

Jhansi was selected in the third stage of the SCM in 2017 and has undertaken 66 projects, completing 65. Its all-India rank is 11.

“Jhansi is a heritage city. So, we took up projects here keeping in mind the history and culture. The people have felt the change in the last few years. We worked to provide green spaces to the people by beautifying the old parks,” said Praveen Gupta, general manager (projects), Jhansi Smart City Limited (JSCL).

This strategy is not uncommon for many ‘heritage’ cities, from Ajmer to Lucknow, where history and culture are monetisable assets. JSCL generates around Rs 11 lakh of income monthly through tickets sold to the Dhyanchand Museum, Space Museum, 30 advertisement screens, and the Light and Sound show at Jhansi Fort.

Jhansi’s Smart City budget was also used for a 30-foot-high national flag installed in Maithili Sharan Gupt Park, one of the largest green spaces in the old city, just a few metres from the Jhansi Fort. A placard states that the aim of the tricolour is to spread awareness about the “ideals, hopes, aspirations, and pride” symbolised by the national flag.

Last month, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi took a jibe at Jhansi’s Smart City project in his election rally, referring to the many colourful umbrellas hanging on the road near the fort.

“If smart cities are made by hanging umbrellas, the INDIA alliance will hang umbrellas everywhere. The Prime Minister promised to make 100 smart cities in the country but did nothing in this direction,” Gandhi said.

Nevertheless, in keeping with the original vision for Smart Cities, some attempts are being made to integrate technology into governance to increase citizen participation.

For instance, last year Agra launched its Mera Agra app. Its goal is to cultivate better civic practices using modern technology innovatively and to build systems and solutions around it. To date, more than 5,000 people have downloaded the app.

Hardly any work was done in the marginalised areas of any city. Smart City has not addressed the larger population of any city

-Arvind Unni, visiting senior fellow at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI).

However, some urban experts argue that making the city smart is not the job of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA).

“It’s the work of the Information and Technology Ministry. MoHUA’s role is city planning, not technological overlaying. This is the fundamental flaw in the mission,” said noted architect and urban planner Madhav Raman, co-founder of Delhi-based Anagram Architects.

He pointed out that the SCM, at its core, is a redevelopment and retrofitting project, but there are limits to what this can accomplish.

“Putting LED lights and making drains on the street is not a technological intervention. Our cities’ infrastructure is still at the 1960s level. In the name of a smart city, a few e-governance websites and apps have been put in place,” he added.

The SCM is an example of a “toll-booth model of urbanisation”, prioritising beautification projects in select areas that generate revenue through tourism and so on, while neglecting uniform development, according to Hussain Indorewala, who teaches at Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture, Mumbai.

“What good is a digital app that indicates bus arrival times when the number of buses is insufficient and declining? What is the advantage of digitising solid waste management when its coverage is partial and disposal practices are unsustainable?” he said.

Entrenched inequalities

The concept of a ‘Smart City’ was born in Scandinavian and European cities, where it basically meant enhancing urban areas through cutting-edge technology. In India, the Smart City initiative focuses largely on civic infrastructure projects. But its effectiveness has been subject to debate, with some critics arguing it deepens existing inequalities within and between cities.

Over the decades, India’s cities have expanded in an erratic and unplanned manner. The urban population increased nearly fourfold between 1970 and 2018, reaching 460 million. Another 416 million people are expected to move to urban areas by 2050, per NITI Aayog estimates, bringing the urban share of the population to 50 percent.

In 2014, when Modi pushed for the Smart City initiative, there was considerable public excitement that it would transform urban life in India. Even those unfamiliar with the specifics were enthused by images of gleaming cityscapes and the buzz surrounding the concept. But when the guidelines were released, it became clear that new cities were not being built, but some chosen old ones would get a new lease of life.

Rounds of competition started and the names of selected cities started emerging.

“There was a lot of discussion about this in the first term of the Modi government, but in the second term, the discussion faded. Officials were busy completing the old targets. This is the situation in most cities,” said Arvind Unni, an urban practitioner and visiting senior fellow at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI).

Unni pointed out that another key issue was the mission’s tendency to focus on areas that were already relatively well-developed—such as Delhi’s NDMC or Patna’s Maurya Lok.

“Hardly any work was done in the marginalised areas of any city. Smart City has not addressed the larger population of any city,” he said.

In February 2024, a Parliamentary Standing Committee report on Housing and Urban Affairs also noted that a large number of cities selected for SCM are from bigger states such as Tamil Nadu, UP, Maharashtra, MP, Karnataka and Gujarat. The report further said that bigger and richer cities were more likely to reap the benefits.

“The Committee notice(d) that larger cities having efficient organizational and financial structure like Surat, Agra, Ahmedabad, Bhopal, Varanasi, Madurai, Pune, Indore, Jaipur, etc. have performed well,” the report read. “However, progress of the Mission is slow in many small cities including those in North-Eastern States where city administration lacks robust organisational and financial structure for sustenance.”

The report added that the central and state grants of Rs 1,000 crore earmarked for each Smart City only comprised about 45 percent of the funding. The rest was proposed to come from “convergence” with other programmes (21 percent), public-private partnerships (21 percent), and loans (5 percent), among others.

Larger and more developed cities were better at attracting and using these additional funding sources than their smaller counterparts, especially those from the northeast and Union territories, the committee observed.

The report further said that more smaller projects had been completed than larger ones. The ministry’s response acknowledged this, stating that “73 percent of completed projects are relatively smaller in terms of cost” due to the complexity and inter-departmental coordination required for larger initiatives.

“Not all cities had the capacity to plan large-scale projects. In northeastern states and some Union territories, we faced several challenges. We are continuously monitoring the work in these cities,” SCM Director Kunal Kumar told ThePrint in February.

Also Read: Greater Noida wants to be Detroit of North India. Noida has taught it what not to do

Solace in hashtags

A group of men sought respite from heat outside at a shop in Tajganj’s Malin basti, a stone’s throw from the Taj Mahal, but with overflowing drains at their feet. The Smart City stamp doesn’t mean much to them.

“The drains are still clogged. Water does not come on time. The lights on the electricity poles do not work. Then, what kind of a Smart City is this? You can see the reality of a Smart City here. Big claims were made, but they were all hollow,” said Rakesh Kumar, a resident of Tajganj.

While a few roads, smart metres, and water connections were installed in this area under the SCM, these improvements were not the hi-tech marvels they were expecting.

This disconnect extends to the digital space. Social media profiles of Smart City initiatives are filled with photos of their accomplishments.

In April, the ASCL posted a news clip about the “Mera Agra” app, touting its role in enhancing citizen security, but several residents responded with grievances.

“I have complained on the Smart City App a month ago, but the problem has not been resolved yet,” wrote Manish Son, a resident of Agra, on X.

Yet, most people still love to own the Smart City tag. Especially on social media. It’s a new identity and they are flaunting it. Many Reels and posts use the hashtag with pride even if there is a laundry list of complaints on the ground.

Some even make Reels showing off how their city has changed, geotagging their location as “Smart City”.

“We want to live it and show our city to the world,” said Rishabh Kumar, a resident of Jhansi in his twenties. “We have social media and through it we are becoming brand ambassadors of our city.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)