New Delhi: When Sonali Sharma was preparing for the judicial services exam in 2016 after completing her law degree from Aligarh Muslim University, there were only 400 students in her batch. Today, that number has more than doubled.

During this period, her life has changed as well.

Sharma, now 31 years old, is still surrounded by law books and notes. But her role has shifted from an aspirant to an instructor, teaching the 800-odd students who want to become India’s next generation of judicial officers.

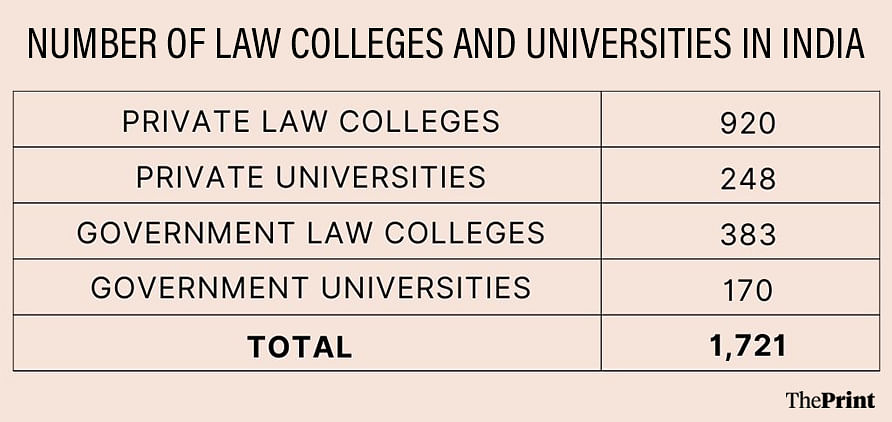

The competition to become a judge in India’s lower courts and tribunals has been heating up over the past few years, reflecting the larger shift in the career choices of graduates. And coaching institutes like Physics Wallah, Study IQ, Drishti IAS, and Unacademy are cashing in. The desire for a government job isn’t limited to UPSC, Railways, SSC, or teaching. With law schools admitting more students than ever—from 1.88 lakh in 2012-13 to 4.32 lakh in 2019-20—many are turning to judicial exams. They are drawn by the job’s social prestige, attractive government perks, and the stability it offers compared to the long hours and high competition in corporate law. The ed-tech company Physics Wallah has now launched a new vertical—Judiciary Wallah—to tap into this growing market.

The judiciary has now become the next gold rush for India’s ubiquitous coaching industry.

“Judiciary is the untouched market, which is being explored by coaching institutes now,” said a former instructor at StudyIQ.

Law was once a profession largely reserved for those with family connections in litigation or corporate law – much like the entitled political dynasty and nepo kids of Bollywood. Judges are still largely viewed as family-run operations, upper caste cabals—the argument often made against the collegium system.

Now, law graduates have struck a proverbial gavel on this mindset. Online court proceedings moved the needle.

“Social media has also played an important role in making the online courtroom available. People started realising that not only IAS and IPS but judges also have powers and they also have social value,” said a civil judge (junior division) in Haryana who cleared the judicial service exam in 2022.

New business for coaching institutes

India’s bustling coaching industry, which once thrived primarily around UPSC and other government exams, has found an untapped gold mine in judicial services. The increase in the number of law graduates has led to a corresponding surge in demand for coaching services.

“In UPSC, the growth has become stagnant, but the judiciary’s growth has been very fast,” said a teacher from an online coaching institute.

For aspirants, the judicial services exams have become an attractive alternative to the long hours and high pressure of corporate law.

Take Physics Wallah, for example. The online ed-tech giant, known for its success in coaching for competitive exams like JEE and NEET, launched its Judiciary Wallah vertical in 2023. Within just two months of offering a free batch, over 8,000 students enrolled, and its first paid foundation course attracted 350 students. By October 2023, the company launched a crash course, drawing 1,800 students in a matter of weeks.

“We currently have 5,000 paid students and an additional 36,000 students accessing our free content on YouTube,” said Atul Kumar, CEO of Physics Wallah’s online vertical.

StudyIQ and Unacademy have followed suit, expanding their course offerings to include judicial services exams. The financial rewards have been immense.

“When we were selling our recorded courses, the revenue was around Rs 5 lakh per month. With 5,000 paid students, it increased to Rs 1 crore a month,” said a former teacher from StudyIQ.

When we were selling our recorded courses, the revenue was around Rs 5 lakh per month. With 5,000 paid students, it increased to Rs 1 crore a month—a former teacher from StudyIQ

Just like other courses, online coaching for judicial services offers the same benefits to aspirants from smaller towns and cities—it’s both flexible and affordable.

The fees for online courses range between Rs 17,000 and Rs 50,000, a fraction of what offline coaching institutes like Rahul IAS charge—Rs 3.2 lakh for one course.

“These online coaching centres are going for every possible space, be it CUET, state PCS, or the judiciary. People in small towns who cannot afford to come to places like Delhi can take classes from home at cheaper prices,” said Amit Kilhor, director of StudyIQ.

More law graduates and more aspirants

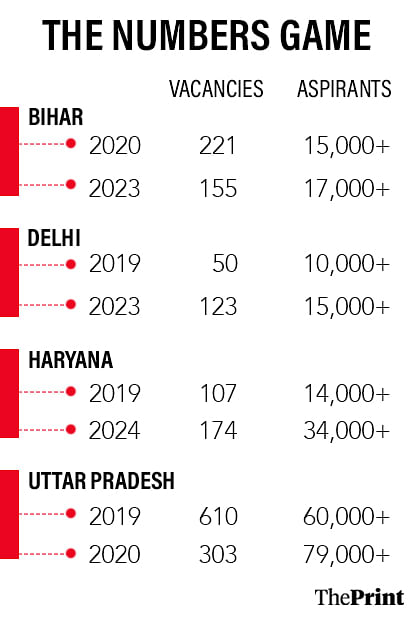

There is, of course, the great paradox about vacancies—while the number of aspirants has gone up, the number of vaccines for judicial officers in many states has gone down.

In Uttar Pradesh, around 60,000 aspirants competed for 610 seats in 2019. Last year, more than 79,000 applicants took the judicial services exam—for 303 vacancies.

In Bihar, between 2020 and 2023, the number of applicants increased from 15,000 to 17,000. But the number of vacancies went the opposite way—from 221 to 155.

This trend is not isolated—Delhi, traditionally one of the most sought-after destinations for judicial service aspirants, saw the number of applicants grow from 10,000 for 50 vacancies in 2019 to 15,000 for 123 posts in 2023.

Law becoming one of the go-to career options for Indian youth is reflected in numbers as well. Many private colleges and universities have come up in the country in the past few years, contributing to more law graduates entering the workforce. According to the education ministry’s AISHE report, between 2012-13 and 2019-20, the number of students enrolled in law courses grew by approximately 130 percent—from 1.88 lakh to 4.32 lakh.

For many of these aspirants, the judicial services exams have become an attractive alternative to the long hours and high pressure of corporate law.

Sahil Kumar, a 28-year-old who graduated from Delhi Law University in 2019, chose judicial services over litigation or becoming a corporate lawyer as these options “require years to establish” oneself. “I am the first in my family to complete law. Judiciary was my best option,” said Kumar, who cleared the Haryana Judicial Services in 2022 after failing to clear the interview round of the Delhi Judicial Services. Kumar did not take any coaching classes, although his friends have all opted for one.

For Preeti Jangra, another aspirant for the last two years, judicial services became the ultimate choice.

“It is the safest option for me. After becoming a judge, there will be no fear of losing my job or even concerns about money. I am a first-generation lawyer, so it has been really hard for me to find a good job with a decent salary, that too without having served time in law firms. There was no one who could endorse me. A government job offers job security, money, and social reputation, and being a woman, there will be perks like maternity and child care leaves,” said Jangra, who will appear for the Haryana Judicial Services examination next year.

But even as the number of vacancies remains limited, the competition for aspirants like Jangra grows fiercer every year. In Haryana, 34,000 aspirants applied for 174 vacancies in 2024—up from 14,000 applicants for 107 posts just five years earlier.

This once-elite profession historically reserved for people with family connections slowly opened up to India’s middle-class with increasing numbers of law graduates and growing vacancies. Even the Supreme Court has shown interest, advocating for the appointment of more judges to handle the country’s growing caseload.

“There was not that much supervision over such exams earlier. Now, even the Supreme Court has said to appoint more and more judges,” said Bharat Chough, a former judge and lawyer.

Law profession largely used to be a family-run operation—much like entitled political dynasty and Bollywood nepo kids. Judges are still primarily viewed as upper caste cabals—the argument often made against the collegium system. Now, law graduates have struck a proverbial gavel on this mindset.

The rising number of law colleges have played a key role. At the same time, more law graduates entering the scene means the competition for judicial positions has become even more intense. Five years in law college may not be enough to acquire the special skill set.

“To clear the exam, one needs a special skill set. The aspirants have to think like a judge; in law school, they are taught like debaters, they are cross-examined. But coaching institutes provide them with the skill set necessary to clear the exam,” said Chough.

In the early 2000s, the appointment of judges was largely a secret affair; even the vacancies were fewer. After 2007-2008, the picture changed and notifications regarding vacant posts started appearing before the public.

“If one does not have family connections in the law field, then it becomes hard to make a name in litigation and corporate law firms. The pay is good but working hours are much longer. And then there is the judiciary, one of the most reputed and secured jobs. That’s why students prefer to go for it,” said a teacher at Delhi Law University.

(Edited by Prashant)

Recruitment to district judiciary has been done through competitive examination since 1970s or even earlier. It was never through discretionary appointment unlike appointments to high court and Supreme Court.

The statement in the article about nepotism while speaking of judicial recruitment for district judiciary is uncalled for and misleading and factually incorrect

Hi Nootan I read all your articles about coaching Industries and I totally agree with you. But Rise of coaching only happened only due to collapse of public education system . Can you please publish some articles how the underfunding of public universities -schools by the govt. is resulting in the rise of this coaching mafia.