New Delhi: Lalit Kumar struggled for two years for permission to add a storey to his Green Park home. Not from the municipal corporation, but from the Archaeological Survey of India. Even minor repairs to his house need ASI clearance, because it’s located within 200 metres of a protected monument.

In Delhi’s heritage-rich landscape, this is a problem that thousands of people have faced due to the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act. Last amended in 2010 under the UPA dispensation, it prohibits construction within 100 to 200 metres of any protected monument. Now, the Narendra Modi government is promising a more ‘people-friendly’ amendment that could reduce the tug-of-war between heritage conservation and urban development.

Sources in the Ministry of Culture told ThePrint that the government is planning to table the amendment in the monsoon session of Parliament.

Over the past decade, the ASI has issued 5,360 show-cause notices in Delhi for construction, repairs, or other work near protected sites. Frustration has built up in neighbourhoods like Green Park, Vikram Nagar, and Nizamuddin, where homes stand cheek-by-jowl with medieval tombs and stepwells.

Even when the Supreme Court raised the height limit under Delhi’s fire rules from 15 to 17.5 metres in 2022, it meant nothing for Kumar. ASI restrictions still barred him from adding a floor to his home.

“Green Park is full of monuments and due to this Act people living in the periphery of 200 metres from any monuments are struggling for any construction or repair work,” said Kumar, president of the Green Park Residents’ Welfare Association.

India has more than 3,000 centrally protected monuments but every monument can’t be placed in the same category. The Taj Mahal and Kos Minars can’t be compared and seen with the same lens

-Sujeet Nayan, superintending archaeologist at ASI’s Patna circle

In recent years, multiple rounds of meetings have been held between ASI and the culture ministry over the issue. Last November, Union Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat said the government is considering changes to ensure preservation efforts cause “minimum interference” in people’s lives.

The proposed amendment aims to allow more flexibility for development in heritage zones. If passed, it could reshape the dynamics of urban planning in Delhi’s historically dense neighbourhoods.

“The AMASR Act needs several changes. We have given our recommendations and now this will be discussed in Parliament,” said Nandini Bhattacharya Sahu, spokesperson and joint director general (Monument), ASI. “The Act will be people-centric and made in such a way that the heritage is preserved and people do not face any problems.”

Also Read: Indian archaeology is getting a cool, new makeover. Out of the trenches, letting people in

Restrictions and resentment

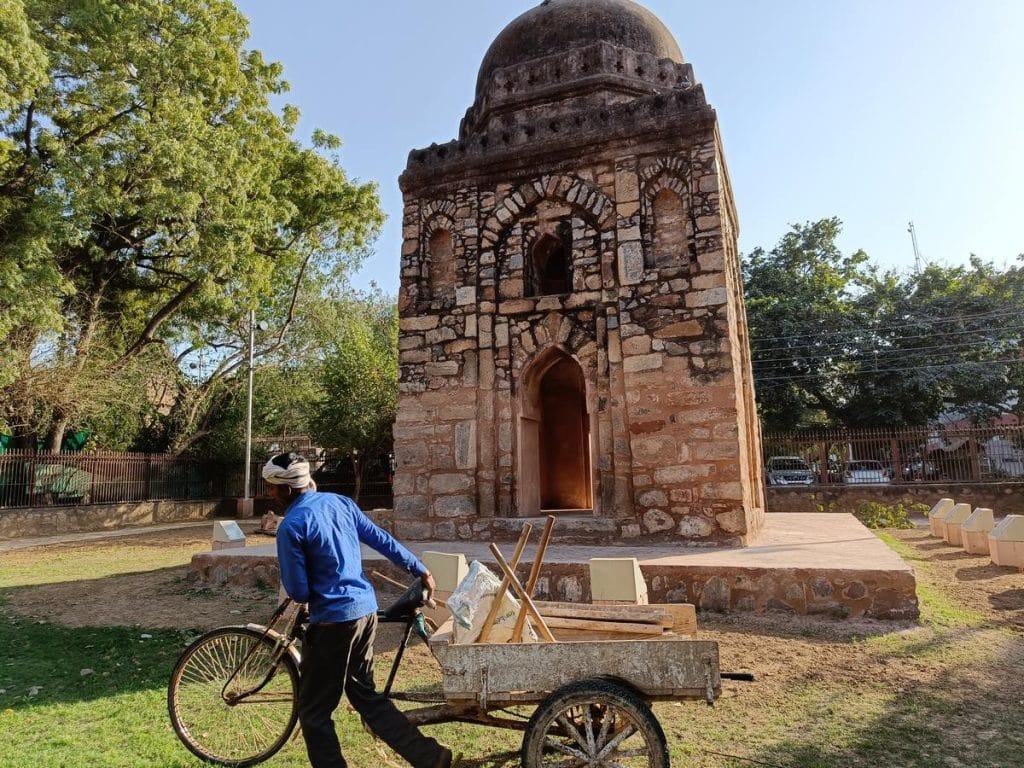

Kumar’s house in Green Park is surrounded by a number of ASI-protected monuments, from Chhoti Gumti and Badi Gumti to Dadi Poti’s Tomb. For residents, these aren’t heritage assets to be admired but barriers to the most basic urban upgrades. Every structural change to their homes needs permission from the ASI.

“Getting approval from the department is not an easy task,” said Kumar, who has met ASI officials with residents’ complaints several times over the last five years to little avail. After doing the rounds of the ASI’s Hauz Khas office since 2023, he finally got clearance for his new floor this year.

“I went through due process, that’s why there was so much delay,” he added.

One of the plots just adjacent to Chhoti Gumti is vacant for the same reason— it falls within the AMASR Act’s 100-metre prohibited zone, where no construction is allowed at all.

The owner cannot build on it due to construction restrictions under the AMASR Act | Photo: Krishan Murari | ThePrint

Similar problems have arisen in Vikram Nagar, where a dense colony is situated near the centrally protected Firoz Shah Kotla monument.

“When anyone starts building, officials come and ask for money. In the name of a protected monument, they are extorting money,” alleged Rajan Chaudhary, president of the Vikram Nagar RWA.

The issue is not limited to Delhi. Across the country, many monuments are surrounded by densely populated neighbourhoods, with the ASI routinely issuing notices for unauthorised activity. On 4 June, the Karnataka High Court even directed the state government to instruct all local bodies not to permit construction around protected monuments without ASI’s approval.

Discussion on the Act is necessary and is ongoing. But if a big building is constructed next to a heritage monument, it will reduce the importance of the monument. The environment around the monument should be kept as it is

-Manoj Kurmi, superintending archaeologist at ASI’s Bhopal circle

These longstanding tensions have featured in Union government discussions for years, but previous attempts to amend the AMASR ACT haven’t gone through.

The AMASR Amendment Bill was first introduced in the Lok Sabha in July 2017 and passed the following year, but was then referred to a Select Committee chaired by Rajya Sabha MP Vinay Sahasrabuddhe.

It submitted its report in 2019, recommending that construction limits be decided case by case rather than applying a one-size-fits-all 100-metre ban.

The report noted that “the pressure for such an amendment in AMASR Act” came up when the ASI declined permission for a six-lane highway near Akbar’s Tomb at Sikandra, Uttar Pradesh. It also cited other stalled infrastructure projects, such as the proposed railway station near Rani-Ki-Vav in Gujarat, work on the Kolkata and Ahmedabad metros, and a bridge over the Panchganga river in Kolhapur—as further reasons for change.

The committee tabled its report in February 2019, two months before the parliamentary elections. But with the term of the Lok Sabha nearing its end, the report was never discussed, and the Bill lapsed.

After this, the call for reform resurfaced in 2023, when the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM-EAC) released a report titled ‘Monuments of National Importance – Urgent Need for Rationalisation’.

It pointed out that India currently has 3,695 Monuments of National Importance (MNI), all under the care of the ASI, but the list has not been comprehensively reviewed since Independence. As a result, it argued, the designation has become “unwieldy” and “needs to be immediately scrutinised and rationalised”. It flagged the AMASR Act as a part of this issue.

“One of the major sources of the problem plaguing the identification and preservation of monuments of national importance lies in the AMASR Act, 1958 itself,” the report noted. “Neither the Act nor the National Policy for Conservation (2014) have defined what the term ‘national importance’ means.”

The absence of clear criteria has made it harder to prioritise and enforce protections. The 2010 amendment mandated NMA to prepare bye-laws for all the monuments of national importance but it has done so for only 126, most of which are awaiting the nod of ASI. Meanwhile, without site-specific rules, ASI resorts to blanket restrictions, fuelling the clash between conservation and development.

In the last few years, several MPs have asked the government to amend the AMASR Act.

“The government has taken a decision to examine the legal issues affecting construction-related activities around protected monuments and sites in order to allow for infrastructure while at the same time, preserving the rich heritage of the country,” said G Kishan Reddy, former culture minister, in a written reply in the Lok Sabha in 2023.

With the bill now expected to come up in the ongoing monsoon session, ASI sources said the proposed amendments would allow some construction work in currently prohibited areas and create separate categories of monuments, each governed by different rules.

“The current restriction is affecting the public works and development projects,” said an ASI source, declining to be named.

But how far the law should bend has become a matter of debate.

Also Read: Does Kashmir’s history begin and end with Islam? First excavation to explore the unknown

‘Every monument is different’

While some within the ASI argue that monuments vary too widely to be governed by uniform rules, others worry that relaxing restrictions will open the floodgates to commercial encroachment.

“India has more than 3,000 centrally protected monuments but every monument can’t be placed in the same category. The Taj Mahal and Kos Minars can’t be compared and seen with the same lens,” said Sujeet Nayan, superintending archaeologist at ASI’s Patna circle.

He added that several rounds of internal discussions have already taken place across ASI circles, but that “recommendations are waiting for a final nod from the government.”

Even as ASI prepares for more flexible regulation, some experts are sounding warning bells about what that might open the door to.

After the PM-EAC report was released, retired IAS officer EAS Sarma, a former secretary in the ministries of power and finance, wrote an open letter to the Ministry of Culture.

“For a long time, real estate developers have been eying the lands surrounding archaeological sites and monuments for commercial development especially in view of urbanisation around those sites and land values skyrocketing,” he argued.

Some archaeologists echo that note of caution about watering down the Act, although there is general consensus that the law needs re-evaluation.

“Discussion on the Act is necessary and is ongoing. But if a big building is constructed next to a heritage monument, it will reduce the importance of the monument. The environment around the monument should be kept as it is,” said Manoj Kurmi, superintending archaeologist at ASI’s Bhopal circle.

The ASI already has a “proper system” in place for issuing No Objection Certificates (NOCs) to citizens, he added.

The irony, though, is that enforcement itself isn’t working as intended. Whether notices are sent or not, encroachments continue around protected sites.

Senior archaeologist and former ASI eastern zone regional director Phanikant Mishra said the AMASR Act is not being strictly enforced, and very few FIRs are registered against encroachers under the relevant sections.

“Court proceedings are also very slow, and cases are not filed judiciously,” he added. “With measures like awareness, community involvement, and buffer zone creation, ancient monuments can be effectively preserved from encroachment within the framework of law.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)