Jammu: For the past week, Sarla Bhat’s younger sister has been gripped by sudden waves of grief. Sometimes, by memories of their playful gardening days in Anantnag. At other times, by the gruesome image of Bhat’s dead body, deserted in the middle of the road after being tortured. Her hands and neck covered with cigarette burns.

She never got to say goodbye. Not being there to perform her sister’s last rites still haunts her.

“I was in Jammu when I heard about my sister’s killing,” she said. “The next thing I remember, I was in a hospital bed for a fortnight,” her voice trembles as she sits on the bed in the living room of her two-storey house in Jammu.

And now, the grief has returned.

Thirty-five years after Sarla Bhat was abducted, tortured and shot dead, the State Investigative Agency (SIA) of Jammu and Kashmir police has reopened her case. It’s caught the family off guard. They had given up hope for justice that was denied to them.

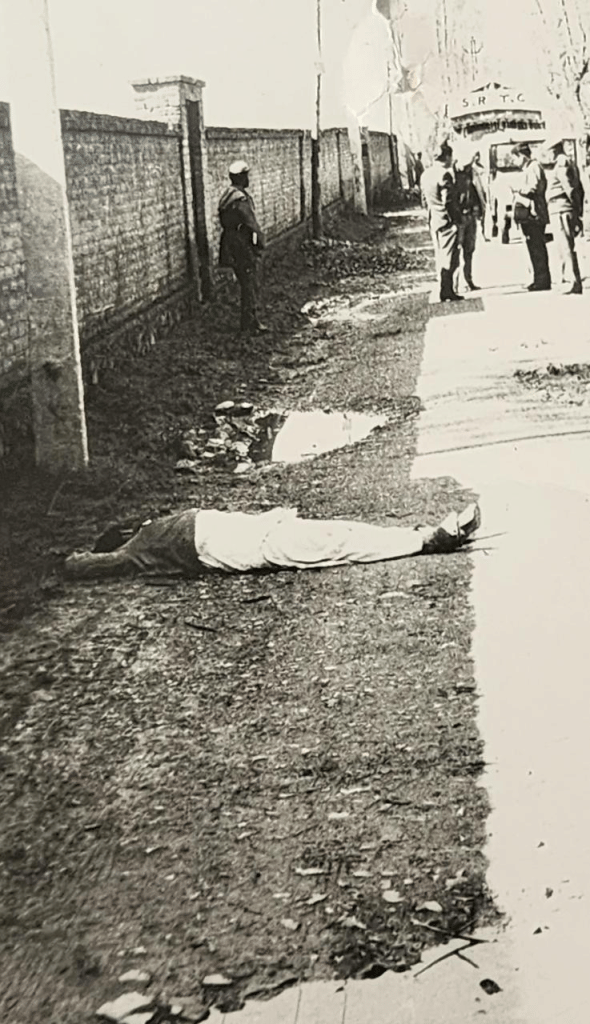

Bhat’s killing marked a turning point in the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. The sight of her bullet-ridden body dumped in downtown Srinagar with a note—branding her a mukhbir (informer)—shattered whatever little hope the community had of staying in the Valley. Soon after, the remaining Pandit families, who hadn’t yet fled, began leaving under the cover of the night.

And now, the news of Bhat’s case has revived memories of the 1990s in the Kashmiri Pandit households—most of whom now live in Jammu, with a few still in select pockets of the Valley.

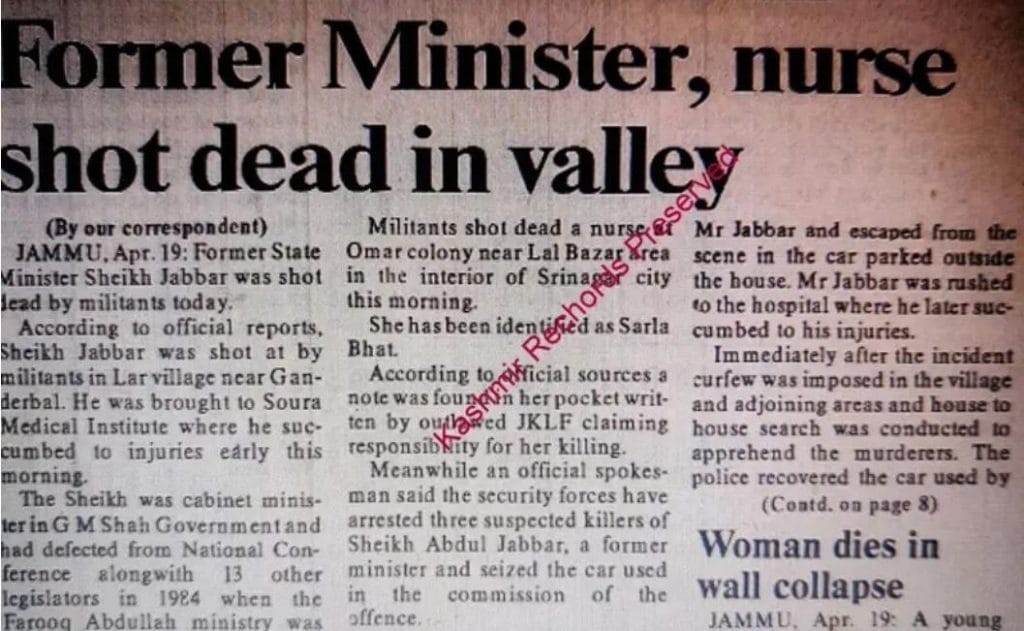

However, when she was killed, her death hardly made the news. A local paper on 19 April 1990, summed it up in a single line: “Former Minister, nurse shot dead in Valley.”

These old wounds have returned to dinner table conversations—about the targeted killings of neighbours, friends, and families. About the massacres. About Wandhama in 1998, when 23 Pandits were lined up and shot in the dark.

The times are different now. India has changed. In Modi-ruled India, there is a greater empathy and willingness to make room for Kashmiri Hindus’ struggles. Movies such as The Kashmir Files are a hit. The Pandits are a rising voice in public conversation. There is an overall acknowledgement of a wilfully ignored tragedy. But that doesn’t make the investigators’ job any easier.

For the SIA, which has raided eight locations in Srinagar, including JKLF leader Yasin Malik’s home, in connection with the case, it is one of the most challenging cases in its files. Several suspects are dead. Evidence is scarce. And key witnesses have dried up.

But for Pandits, it is a rare shot at justice.

Right after her murder, an FIR was registered in the case under Sections 302 (punishment for murder) and 120B (criminal conspiracy) of the IPC, and Section 3(2) (punishment for terrorist acts) of the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA). But the it didn’t move forward.

“During the 90s, terrorism was at its peak. The atmosphere in Kashmir was so charged that the police and investigating officers were hesitant to take up these cases,” a senior SIA official told ThePrint in Srinagar. “In a few cases, we even lost officers to terrorists. After the Pandits left, the situation in Kashmir changed so rapidly that cases went into cold storage.”

In 2017, the Supreme Court refused to reopen the cases of Kashmiri Pandit killings, questioning where the “evidence will come from.” For Pandits, it was another door slammed shut.

That was when community groups approached Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha. In 2023, Sinha ordered J&K Police to prepare a list of killings from the 1990s—a move that eventually led to the reopening of Bhat’s case, an SIA official said.

After the Pandits left, the situation in Kashmir changed so rapidly that cases went into cold storage.

a senior SIA official

Also read: Kashmiri Pandits are reviving old hometown temples. ‘It’s how we will return’

Tracing the steps

A note recovered from Bhat’s dead body has become the key piece of evidence in the investigation. The note read: “This girl has been killed by JKLF for being a mukhbir to the CID.”

It ended with two signatures of Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) terrorists claiming responsibility. The SIA has denied any evidence of Bhat’s involvement in passing information to the CID. At the time of her death, she was a nurse at the Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences in Srinagar. The SIA said the killing followed a general “protocol” used in the targeted killings of Kashmiri Pandits during the 1990s.

Now, the SIA have returned to old-school investigative methods, launching elaborate raids across Srinagar—with the same note in hand. Now, they are matching the handwriting.

“In the 90s, there were no smartphones, laptops, or other digital modes of communication that could be seized. Now, we are analysing the seized documents through experts,” an investigating official said.

The SIA is also examining the possible role of Bhat’s colleagues, including the then Head of Department Ahad Guroo, in potentially facilitating JKLF terrorists’ entry into the institute, which eventually led to Bhat’s abduction.

After more than three decades, the SIA is now shouldering the burden of procedural lapses, botched investigations and missing files. In April 1990, shortly after Bhat’s murder, two JKLF terrorists were killed in an encounter. Their weapons were seized, but never subjected to ballistic analysis to check if they matched the weapon used in the murder.

Even the handwriting on the note was never compared with documents recovered from the JKLF operatives over the years, said a senior police official. Eight JKLF operatives were involved in the killing—one is in Pakistan, three are dead, one is in jail, and two are out on bail.

Another JKLF terrorist, Noor Ul Haq, was interrogated in connection with the case, but the report has gone missing. Now, the SIA is left with the original FIR filed—its writing faded with time—and the note, the photo which the officials carry in their smartphones.

And so, the SIA is starting from scratch—revisiting old colleagues, digging through the newspapers, and even analysing social media posts—piecing together whatever fragments they can to reconstruct the story of Bhat’s killing.

A living tribute

In a small, cramped apartment in a Kashmiri Pandit camp in Jammu, unlikely visitors are knocking on the run-down wooden door of Moti Lal Bhat’s house. He is Sarla Bhat’s uncle.

From Kashmiri Pandit activist groups to political leaders and the media, everyone wants to speak to him, show their support. But he keeps brushing them off, asking angrily, “How come you all have woken up now? Where were you for the last 35 years?”

As he shuts the door in their face, regret weighs heavily on his shoulders, slumping his short and wry body further in the grief.

Moti Lal still regrets not taking his brother, Shambu Nath and his daughter, Sarla, along with him to Jammu. He recalled trying to convince his elder brother to leave Kashmir during the peak of militancy.

But his elder brother wanted Sarla to wrap up her work and complete the formalities at SKIMS in Srinagar before returning.

On 11 April 1990, Moti Lal left for Jammu, abandoning the family’s newly built three-storey house in Anantnag’s Qazi Bagh. They had moved in barely two months earlier.

Three days later, he received a call about his niece’s death. And for the next six months, the two brothers ran pillar to post seeking justice for Sarla.

“We went to the secretariat, to the police, the higher authorities. All we were told was that they would take up the case. They never did,” thundered Moti Lal, a cigarette stubbornly held between his fingers.

Taking a long drag, while looking at the ceiling, he recalled his niece’s body, lying in the street—just metres away from the militants killed in an encounter.

“The locals took the bodies of the militants to the hospital while they left my daughter to die,” he said, as a tear rolled down his cheek. The cigarette had long burned to ash, but he still held it between his fingers, unaware.

A weak smile flashed across his face, “Sarla was very Chulbuli, bold and way ahead of her time.”

A graduate in English Literature from a government college in Anantnag, Sarla wanted to serve the people. That is what led her to pursue a BSc in Nursing. Soon, she was working as a nurse at SKIMS.

“She had a round face, a blunt haircut, and a love for gardening. She would chase after me with a stick if I accidentally killed one of her plants,” said her younger sister. Now, she tends to a small garden at her home in Jammu, caring for each and every plant—a living tribute to Sarla’s memory.

How come you all have woken up now? Where were you for the last 35 years?

Moti Lal Bhat, Sarla’s uncle

Also read: Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir are branded as kafirs, boycotted, spat at. They hide, pass as Sunnis

An undignified funeral

When Sarla’s body was brought home, a hand grenade was hurled at the main door—a welcome the family never forgot. They never learned who carried out the attack.

“Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims, both, were coming to our house to offer condolences. It was impossible to know who could have done something so insensitive,” said Sarla’s younger sister.

From that moment, until her cremation, they kept the windows shut and the door bolts fastened, fearing another strike.

But what happened the day after the cremation still sends shivers down her sister’s spine. She recalled that when her father and other men of the house had gone to bring her ashes, they were stopped by a group of men, trying to snatch the bag from their hands.

“They threatened and said that your daughter was an informer and responsible for the killing of 10 militants,” she said, remembering what her father told her about the incident.

That very night, the family left Kashmir and their house in Qazi Bagh. And now, every year from 12 to 14 April—as the exact date of Sarla’s death remains unknown—her sister, brother, and parents mourn her loss and make donations to the poor in her memory.

The post-mortem of Sarla’s body had ruled out rape, the family said. But she was brutally tortured, they said: cigarette burns on her wrists and neck.

The locals took the bodies of the militants to the hospital, while they left my daughter to die.

Moti Lal Bhat, Sarla’s uncle

Sarla’s killing devastated her family but also instilled a deep sense of fear among the community members.

Rubin Saproo had never met Sarla, but he lived just 4 km away from her in Kashmir. He was only 14 when the news of her death had spread like wildfire, forcing Kashmiri Pandits in the neighbourhood to lock themselves inside their houses.

He recalls how at 7:30 pm, the local news broadcast on radio, the only source of communication, announced her death.

“All Pandits had shut the lights of the houses, closed the curtains and turned on the radio to listen to the news. Such were the days,” said Saproo, now living in Jammu.

Also read: A Kashmiri Pandit woman’s marriage to a Muslim is threatening peace in Pulwama

Not a high-profile killing

The news of Bhat’s killing received little attention in the newspapers. But Kashmiri journalist Ahmed Ali Fayyaz continued speaking about her over the years—through talk shows, in his articles, and now, after the case has been reopened, on social media.

In his latest tweet on X, Fayyaz wrote how Bhat’s killing “had little prominence as compared to Tika Lal Taploo (killed in September 1989), Neelkant Ganju (Nov 1989), Lassa Kaul (Feb 1990) and Sarwanand Kaul Premi (May 1990).”

“Back then, Sarla Bhat’s killing was not seen as a high-profile murder,” Fayyaz told ThePrint.

In the 1990s, SKIMS was the main hideout of several militant organisations.

“Professors and HODs were openly identifying themselves with the militant organisations. One would find posters of guerrilla groups on the walls and corridors,” said Fayyaz.

Sarla Bhat’s killing coincided with the hospitalisation of—now jailed—JKLF leader Yasin Malik at SKIMS. Fayyaz recalled that Malik had injured himself while jumping from a third-floor window during a search operation and was admitted to the hospital, posing as a civilian.

“Militants would call SKIMS ‘IMS’ — removing Sher-e-Kashmir from its name. Such was the hatred against the National Conference and Sheikh Abdullah,” Fayyaz added.

According to a senior police official, during the operation around Yasin Malik’s stay at SKIMS, the hospital’s then Head of Department, Ahad Guroo—now deceased—was arrested and later released after interrogation.

Given Guroo’s proximity to JKLF, the militant group scanned through the profiles of employees working at the hospital during the leader’s stay, said the officer. JKLF suspected a mole had leaked the information that led to Guroo’s arrest.

“It is said that someone close to Sarla gave her name, saying she was a Kashmiri Pandit and therefore an obvious suspect,” the official noted.

On the night of 12 April, as Sarla was returning from the hospital to her hostel within the SKIMS premises, militants in a white Maruti abducted her. Two or three days later, her tortured body was brought in an ambulance and dumped on a street with a note in the pocket of her shirt.

The police are also investigating the role of Yasin Malik and another former militant, who is currently out on bail, in the case. The police said one of the accused is currently in Pakistan.

In 2009, during his talk show Face to Face with Ahmed Ali Fayyaz on Take-1 Channel, Fayyaz interviewed former JKLF deputy commander Showkat Bakshi, who made an indirect admission about Sarla Bhat’s killing.

“I asked Bakshi about Sarla’s killing,” he recalled. “He said there were some black sheep among us who came before us after training from Pakistan. But I told him, these incidents were claimed by JKLF, so it is your responsibility.”

At the time, Fayyaz said, it was common for ex-militants and separatist leaders to appear on such interviews, unlike today.

Living in unease

With the reopening of Bhat’s case, a wave of misinformation has also surfaced on social media—including confusion between the killing of Sarla Bhat and that of Girja Tickoo, another Kashmiri Pandit woman who was gangraped, murdered, and mutilated.

Sarla’s family told ThePrint that incorrect photos of her have been widely circulated online. “It caused us a lot of trouble to see incorrect photos and wrong story details attributed to her,” her younger sister said.

During her time at SKIMS, Sarla would visit her home in Anantnag every weekend. But the weekend she was killed, she didn’t come home. With no means of communication and Kashmir under curfew, the family knew something was amiss.

Her younger sister was 20 then. The eldest of three siblings, Sarla was the one everyone looked up to. Even at the height of insurgency, she would urge her family to stay back in Kashmir.

“She was very brave. She would tell us, ‘Don’t leave Kashmir. It’s our land. Nothing will happen to us’,” recalled a cousin who was in Class 9 when she was killed.

The daughter of a government school headmaster, Sarla was remembered by her cousin as a free thinker—passionate, fearless, and determined to live on her own terms. And her death has left her family on tenterhooks even decades later; they now keep tabs on each other, share their locations before stepping out, and live with constant unease.

For her younger sister, one thought remains unbearable: “What was my sister feeling in those three days? She went through all this alone? She must have been tired, planning to rest at her hostel. Did she have a premonition that something was wrong?”

For their father, who has undergone heart surgery recently, the reopening of the case reopened a wound he has long tried to suppress.

“My brother and I don’t talk about Sarla and the case much in front of our parents,” said her younger sister.

Their mother, who never recovered from the shock, still struggles with words in Hindi.

“Sarla’s mummy can only speak in Kashmiri,” said Sarla’s cousin

On the day the case was reopened, their father, Shambu Nath, went through every file, every yellowed newspaper clipping, every document he had gathered over the years. That night, he could not sleep.

“Uncle has been sick for days,” his neighbour in Jammu said. “He hasn’t come out even for his daily walk.”

Back in Anantnag’s Qazi Bagh, a Kashmiri Muslim family now lives in the Bhat family house—the newly built house they sold in distress after they fled to Jammu. The lanes are unchanged, the neighbours the same, but no one remembers Sarla anymore. Or maybe, they don’t want to.

Once a bustling Kashmiri Pandit locality, Qazi Bagh today doesn’t have a single Pandit household left.

For the last 35 years, neither Shambu Nath nor his brother Moti Lal has set foot in Kashmir. “We haven’t visited Kashmir, nor do we want to. Kashmir ceased to exist for us the day Sarla was killed,” said Moti Lal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)