Chandigarh: The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute Of Microbial Technology’s Protein Laboratory in Chandigarh has all the typical assets of any science laboratory—shelves of conical flasks, petri dishes, and test tubes. Amid the silent hustle of the laboratory, however, a new language is taking shape.

Twenty-six-year-old Hoshiyar Singh is trying to understand the difference between the words ‘precision’ and ‘accuracy’ in science. The answer can make a world of difference to India’s hearing-impaired students. How the two words are conveyed in sign language will contribute to making STEM truly accessible.

Out of a storeroom-turned-studio—equipped with a green screen, a laptop, some lights, and a camera—a students’ group is creating engaging science videos but in silence. About a hundred signs that express and explain basic science terms like algae, protein, or atom have been created by the group, many of which are already uploaded on their website.

With every new hand sign, they are getting closer to the world of science.

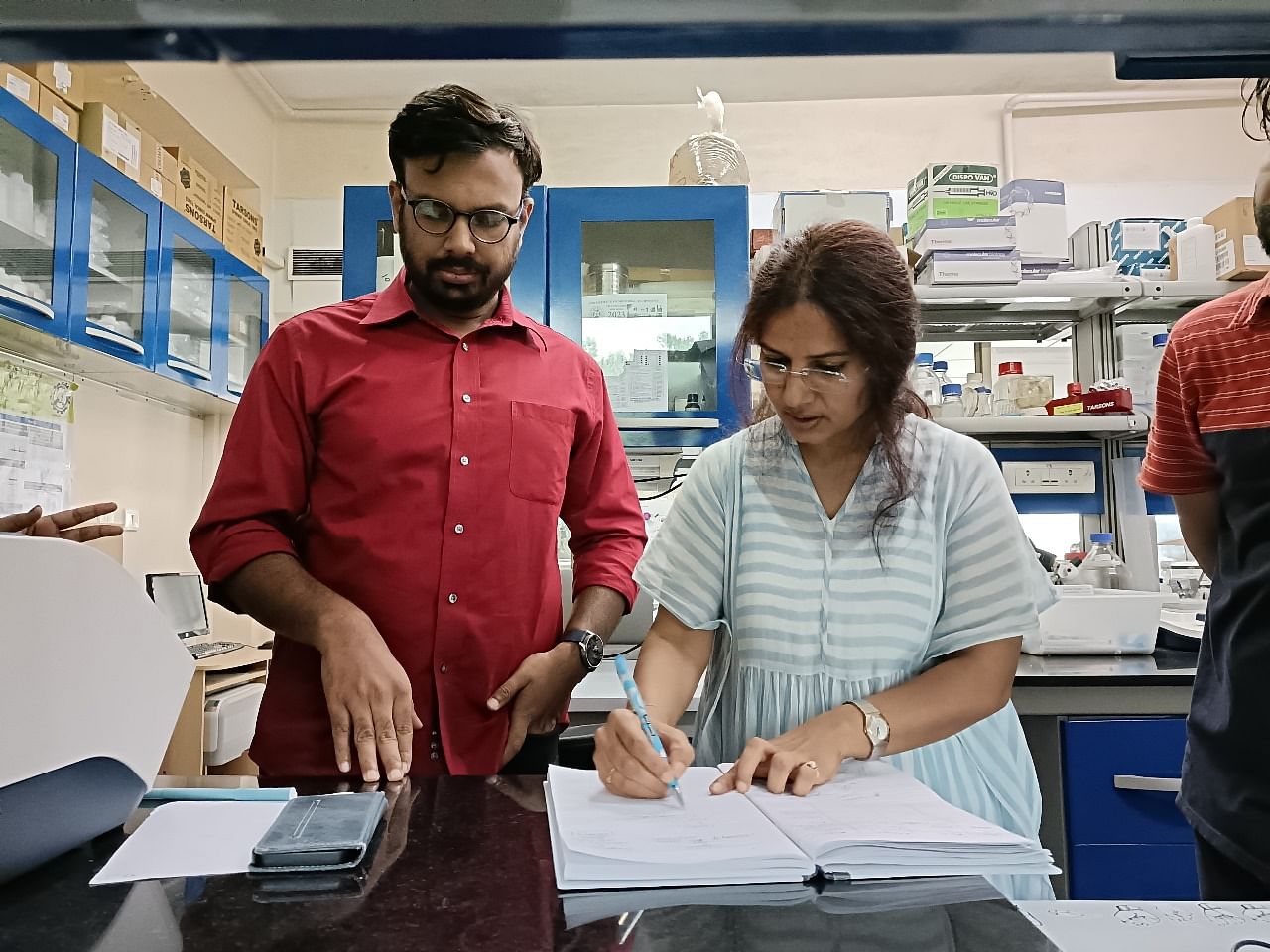

These students are hearing impaired but have a keen interest in science. Under the guidance of the lab head Alka Rao, they are working on developing popular science videos in the Indian Science Language (ISL).

Funded by the CSIR’s Jigyasa Programme, the Indian Sign Language Enabled Virtual Laboratory (ISLEVL) has so far translated over 100 science videos produced by CSIR labs into ISL. In the process, Rao’s team is also developing an ISL vocabulary for STEM subjects.

“Loss of hearing for these students is seen as a limitation, but in fact, it can be a strength. The deaf student community represents an untapped human resource with immense potential—if we can empower them to communicate science,” Rao told ThePrint.

Rao was volunteering at the Haryana Welfare Society for Persons with Speech and Hearing Impairments (HWSPHSI) when she realised that even though students have a keen interest in science and want to know what happens in science labs, translators do not have the words to express what she was trying to tell them.

Also read: Delhi HC to use services of sign language interpreters on provisional basis

Building a vocabulary

According to Pallavi Kulshreshtha, advisor at HWSPHSI, most people with hearing impairments are unable to read and write at age-appropriate levels.

“Simple concepts of science like how rains and earthquakes take place are not clear to them. The sources from which they can get information are also limited,” Kulshreshtha said.

Most NGOs also only provide basic knowledge of the English language. Science stream is not offered in deaf schools, Alka Rao

As an example, she said that the fake news story about the Indian Rs 2,000 note having a GPS chip was true for the deaf community for a long time—the fact check for it never made it to them.

“People cannot access information, so there is a huge gap in basic knowledge,” she said. Even when they complete their education from school, they realise how big this gap is during their job interviews. “Most NGOs also only provide basic knowledge of the English language. Science stream is not offered in deaf schools.”

Having worked with hearing-impaired students for many years, Rao said that the lack of vocabulary was the primary reason that the deaf community was being left out of science education.

“Deaf students were scared of science. There are so many words that simply can not be expressed in sign language. Usually, when the translators encountered such words they would just sign using alphabets,” she said.

Rao decided that there was a pressing need to create such content that was accessible to hearing-impaired students. With funds from the Jigyasa programme, Rao has employed three hearing-impaired youngsters — all under the age of 30 — to work with her in the lab.

The team decided to start small. They began by picking videos published by the CSIR labs in the country and translating them. Simple as it may sound, by no means was this an easy task.

Rao knows only the basics of ISL. Interpreters did not fully understand the science they had to translate—or even the concept behind the words that Rao thought would need to be included in the vocabulary.

But her faith was unwavering.

“We know that the loss of one sense heightens others. In my experience, deaf students are patient and very focussed when they work,” she said.

Also read: Awareness should be created in society about hearing loss among children: Bhagwat

Going beyond the basics

With the help of interns from the Indian Sign Language Research And Training Center (ISLRTC), who work as translators, she would explain scientific concepts to the hearing-impaired students—who in turn began to invent their own signage for the words.

Digvijay Singh has a bachelor’s degree in Arts. The 30-year-old lost his hearing during a childhood illness. Rao teared up while introducing him to ThePrint. “He is the one holding the weight of the project on his shoulders. You should see how hard he works—sometimes he spends weeks to understand a concept,” Rao said, lovingly throwing her arm around Singh.

Singh stands in front of the camera with an infectious, confident smile. His eyes light up as he communicates using sign language, his expressions conveying a lot more than simple English words ever could.

With the help of Theresa Arulavti, an ISLRTC intern at the lab, Singh said that he did not want to take the simple route in this project.

“I first read about the subject and understand the word properly before thinking of a sign. I take feedback from scientists to ensure that the word expresses the true meaning,” he signed.

While recording, Vivekanand Jaiswal, another hearing-impaired student in the project, watches Singh to ensure he properly understands the language.

Singh said that there is no STEM education in India for hearing-impaired people. Having been part of several workshops, he is very happy to see the positive feedback.

Ashish Ganguly, Chief Scientist at the CSIR-IMTech, said he has seen a drastic change in the students over the course of the year.

“Earlier when they joined they were very shy and kept to themselves. But look how confident they are now. They feel a sense of belonging at the institute, it’s really a pleasure to see that change,” he said.

Indeed, Rao has given the students the autonomy to shape the project themselves.

“Some of the STEM words already exist in American Sign Language. Initially, I would get very confused as to why they did not want to simply adopt some of these words and move on with the work,” she said.

In the context of STEM education, it is crucial to address the representation of women in these fields. Studies show that only 13.5% of STEM faculty in India are women, highlighting the need for initiatives that promote inclusivity and diversity in science and technology.

However, Singh explained that some of the words do not come naturally to the way Indians sign. For example, the sign for ‘protein’ in American Sign Language comes with a shoulder jerk that is not natural to ISL users. Instead, he has modified the sign slightly to suit ISL, which is a much smoother movement.

These are things that only ISL users fully understand, so they should be the ones at the helm of developing the language, lab head Alka Rao

Just like spoken languages have dialects and cultural aspects, there are similar cultural differences between the American and Indian sign languages, Rao explained.

“Facial expressions are a huge part of ISL. These are things that only ISL users fully understand, so they should be the ones at the helm of developing the language,” she added.

For example, ‘algae’ in ASL is expressed by signing the spelling of the word. Singh, with the help of Rao, understood what algae means. The sign he has developed shows an ‘A’ followed by a movement of a finger that gives a sense of something being alive.

Another example is that of ‘atom’. In ASL, the sign expresses electrons hovering over a nucleus. “But that does not quite capture what an atom is,” Rao said.

Singh instead thinks it is more appropriate to show the electrons revolving around the atom.

Hoshiyar Singh, a 26-year-old from Gurugram, has worked with post-doctoral students who prepared video materials on basic science experiments. Observing every step, he later shoots a video translating the experiment in sign language for an outreach video.

Even though accuracy and precision may have similar meanings in the English language, in the context of science experiments they have an important distinction. Accuracy refers to how close a measurement is to the true or accepted value. Precision refers to how close measurements of the same item are to each other.

Rao said that such concepts take a lot of patience and time. At the same time, she makes sure that Vivekanand, Hoshiyar, and Digvijay are treated just like any other student. She scolded them when they forgot to put on a lab coat.

The focus of the Jigyasa programme is on connecting school students and scientists so as to extend students’ classroom learning with hands-on research.

Rao has also seen a lot of scepticism from some in the scientific community. “They think it’s a waste of time and money, and that scientists should only be doing science,” Rao said. However, she believes it is part of her responsibility to give back to society using the resources she has in hand.

Her ISLEVL project does not mean that the scientific experiments and research in her laboratory have stopped. Along with research on proteins in her lab, Rao is also a Member of the National Biodiversity Authority of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. She is also part of the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC).

Also read: Chromosome sketches, rare photos, handwritten notes — glimpses from the life of MS Swaminathan

New beginnings

According to the last Census conducted in 2011, the total population of the hearing-impaired in India was 50 lakh.

Kulshreshtha said that less than five per cent of the hearing-impaired children in India go to school. While less than 0.1 per cent choose higher education.

It will be very interesting to demonstrate this science in silence, Principal Scientist

It is important to bring the students to the laboratory, Rao said, adding that it is much easier for them to pick up concepts when they see the experiments in real time.

Rao added that the involvement of CSIR in the project will ensure that the work is institutionally backed, and does not just die out. The team is now planning to sign an MoU with ISLRTC to formally include the words developed by Rao’s team in the ISL dictionary for wider usage and standardisation.

Rao’s colleagues share her enthusiasm. A team of the institute’s top scientists are now gearing up to host an event, sponsored by the Royal Chemical Society, where they will host over 60 hearing-impaired students from three schools in Haryana.

Leading scientists from the university will conduct a three-day hands-on science workshop aimed at sparking the interest of students in STEM fields.

Ganguly considers this a unique challenge. “I think I am going to try to invoke some awe among the students with colours and crystalisations.”

Raman Parkesh, Principal Scientist, told ThePrint, “For thirty years, we have only worked with people who know our language. It will be very interesting to demonstrate this science in silence,” he said.

The work is very close to Senior Principal Scientist S Kumaran’s heart.

“My sister had a hearing disability. Believe me, she is the most intelligent person in our family. But she ended up dropping out of school after class 9,” he said. It was due to a lack of options for her to get a proper education that catered to her language needs.

Kumaran is happy to be a part of a project that could make a definite change in the lives of hearing-impaired students.

We should have been doing this several years ago, Sanjeev Khosla, CSIR-IMTech director

CSIR-IMTech Director, Sanjeev Khosla, said that for many years there has been a realisation that while disseminating science, disabled children were not being brought into the fold.

“Many times specially-abled students have the ability to understand science in a very different way and that they can actually develop important concepts about scientific findings,” Khosla said. The hearing-impaired students ask questions the institute’s scientists have never even thought about.

“This is very important for the scientific community. We should have been doing this several years ago,” he added, applauding Rao’s efforts.

Rao said she is aware that her work is far from over, but she takes pride in the fact that she is able to generate employment in the laboratory for at least a few of the students.

“With just three students and a small budget, we have managed to make 100 videos and improve the vocabulary by 100 words. Imagine the impact this would have if the project can be scaled up,” she said.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)