India’s rights watchdog NHRC — labelled ‘toothless tiger’ — is swamped with cases but has little resources to address them. This, despite an ‘A’ rating from UN body.

New Delhi: On paper, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), which turned 25 last week, is a success story.

In February, the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), a UN body based in Geneva, re-accredited India’s apex rights watchdog with the ‘A’ status, a perfect score.

Cases are resolved within months and compensation is granted in 90 per cent of them, so say NHRC statistics.

Yet, on closer inspection, the ‘impeccable’ record starts to unravel.

Much of the complaints that come to the commission are dismissed even before a preliminary hearing, and critics argue that the NHRC shies away from contentious cases with political implications.

Short-staffed and inadequately funded, the watchdog also lacks the required infrastructure to handle India’s civil rights violations.

Such is the situation, that its own chairperson, former chief justice of India H.L. Dattu, himself has called the NHRC a “toothless tiger”.

It’s an assessment that the Supreme Court agrees with: Last year, while hearing cases relating to alleged encounter killings in Manipur, the court observed that there is “no doubt that it (NHRC) has been most unfortunately reduced to a toothless tiger”.

But on its 25th year anniversary, NHRC highlighted its long list of achievements — disposal of more than 17 lakh cases, payment of more than Rs 1 billion to victims of human rights violations, carrying out over 750 spot enquiries of human rights violations, apart from conducting over 200 conferences to spread awareness of human rights across the country.

As part of the anniversary celebrations, the Modi government has released a commemorative stamp and the NHRC has released a documentary highlighting its achievements.

The documentary refers to its interventions in the 2007 Nandigram violence in West Bengal and Salwa Judum-related incidents in Chhattisgarh as important milestones in developing India’s human rights.

The NHRC also states that its role has been significant in combating encounter killings and custodial deaths. The commissions’s guidelines in 1997 mandates every custodial death and encounter killing be reported to it within 24 hours.

On its 25th anniversary, ThePrint analyses the key structural issues plaguing the NHRC.

Also read: Sigh of relief as Bachelet replaces Kashmir-baiter Zeid Hussein as UNHRC chief

Impact in numbers

Set up in 1993, in the backdrop of criticism against gross human rights violations in Kashmir, the NHRC plays four key roles — protector, advisor, monitor and educator of human rights.

The commission is particularly tasked with independently investigating rights violations committed by the government’s arms.

The NHRC, however, woefully lacks the infrastructure to fulfil its mandate.

In a submission made to the Supreme Court in 2017, the NHRC admitted that despite a 1,455 per cent increase in complaints between 1995 and 2015, its staff strength had decreased by 16.94 per cent in the same period.

In 2015, NHRC’s strength was 49, down from 59 in 1995 while the number of complaints in the same period saw a massive increase to 1,14,167 from 7,843.

Of these cases, custodial deaths, one of NHRC’s focus areas, shot up from 444 to 5,496.

Commission officials have candidly admitted in Supreme Court that with its current staff capacity, it cannot investigate more than 100 cases a year.

Apart from the limited sanctioned strength, almost 50 per cent of the NHRC’s staff is on deputation from other services. These officers keep changing, leaving the commission constantly short-staffed.

The officers conducting investigations are usually on deputation from the same forces that have been accused of violations and will have to inevitably go back to them, creating a conflict of interest.

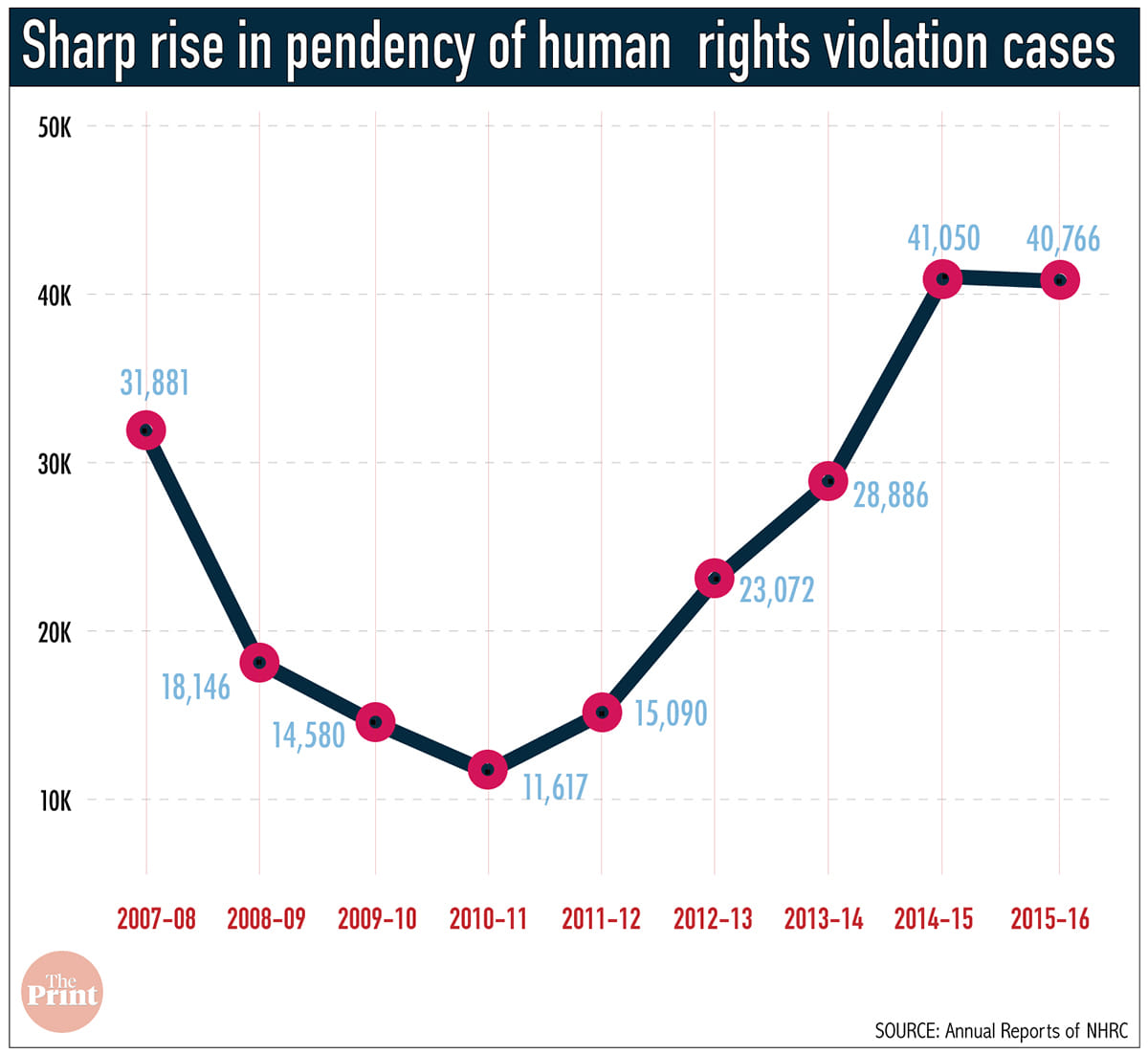

The perennial staff shortage has meant that the NHRC, despite its quasi-judicial nature, has the same problem that our courts do — pendency.

It has also altered the watchdog’s working. Data for the last 10 years (2007-2017) shows that the NHRC has a high rate of disposing complaints.

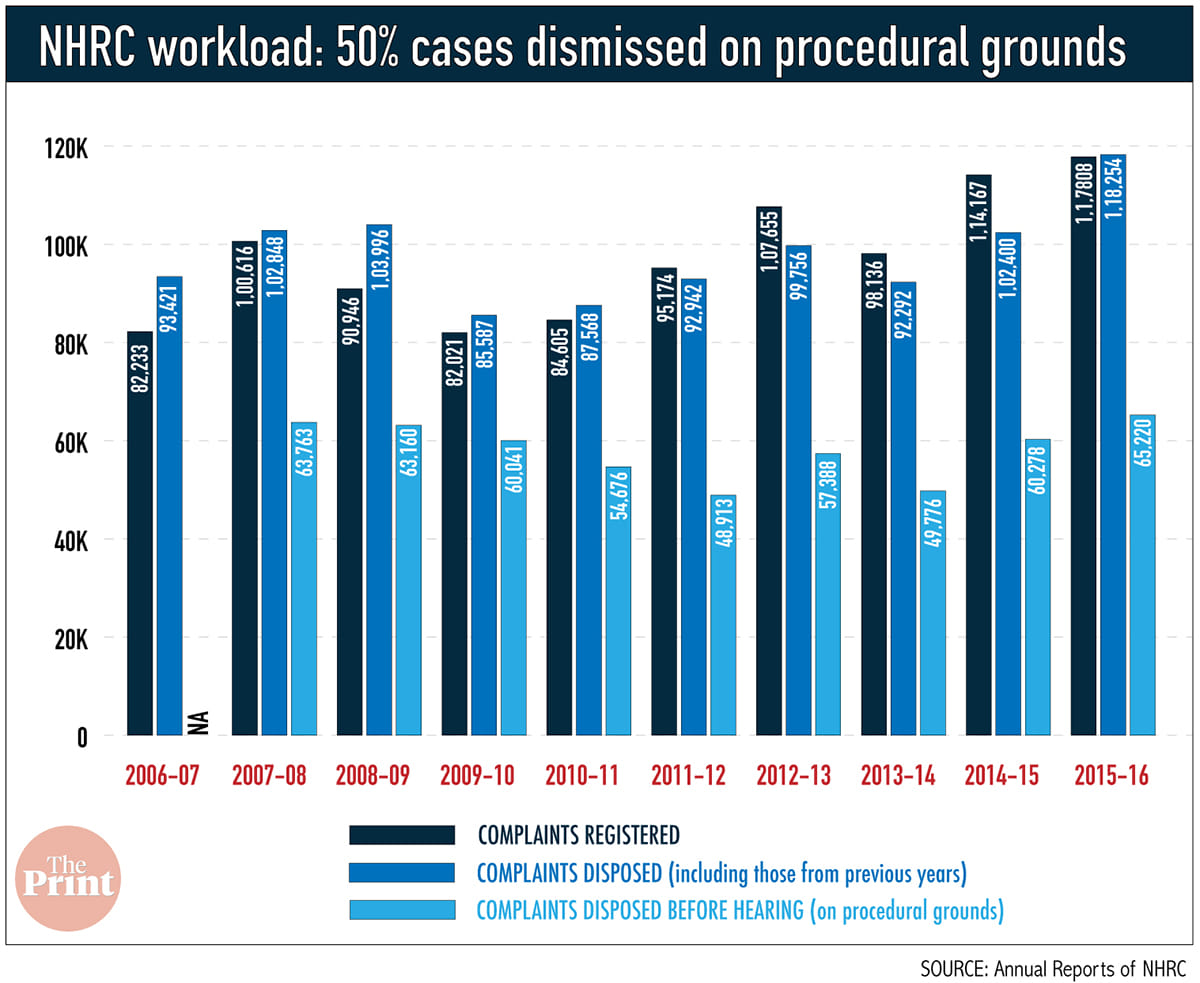

While it ‘disposes’ an equal number of cases or in some cases even more than it receives every year, almost 50 per cent of such cases are simply “dismissed in limine”.

Dismissing a case in limine is putting it away on procedural grounds even before a preliminary hearing without considering it on merits.

“NHRC has a flawed process of verifying complaints. NHRC actually sends it to the police station which would have refused to take action in the first place. Obviously, many of the complaints are simply dismissed,” said Colin Gonsalves, senior advocate and founder of Human Rights Law Network.

Questions of independence and govt interference

The NHRC’s independence has always been in question given that the very state, which causes the human rights violations, has to fund and provide resources to the rights watchdog.

Gonsalves says NHRC’s lack of independence makes it a “lap dog, instead of a watch dog”.

Human Rights Law Network has filed a writ petition in Supreme Court outlining the civil society concerns about NHRC, including its lack of independence. The case is pending for over two years.

“Most instances of human rights violations that the NHRC investigates are against the police and, ironically, the commission comes under the Home Ministry,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

“Unless the NHRC is made truly autonomous and there is political will to strengthen human rights, its powers will remain on paper.”

Civil society groups argue that NHRC has refrained from asserting its independence by not taking up cases with high political stakes.

For example, in 2003-2004, in the aftermath of the communal riots in Gujarat, just 1.7 per cent of the rights cases were from that state. Of the 72,990 cases that year, only 1,268, not all of them riot-related, were from Gujarat.

“NHRC takes cognisance of cases based solely on media reports and not through its on-field work at the grassroots level,” said Vivek Sheoran, a Hisar-based civil rights lawyer. “Obviously, not all human rights violations are reported or get the same media attention and the NHRC intervention also dies when the newscycle ends.”

The NHRC also has no powers to investigate human rights violations involving the armed forces. Since the commission can only send queries to the Defence Ministry, Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur — two states where the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act has been in effect — have seen an abysmally low number of cases of human rights violations.

In terms of action against excess police action, the NHRC has limited itself to custodial death, rape and torture by police and has refrained from venturing into torture cases related to terrorism and insurgency.

The NHRC has told the courts several times that its hands are tied since state governments do not cooperate with it.

In 2017, it told the Supreme Court in an affidavit that “compliance with its directives by the states has only been half-hearted, with several deficiencies such as unexplained delays, sub-quality reports, and illegible documents”.

Appointments

The NHRC is a five-member body that, according to the National Human Rights Commission Act, can only be headed by a former chief justice of India who is below the age of 70. Each head serves for a tenure of five years.

The other members usually include a retired Supreme Court judge and those with expertise or experience in human rights.

The chairperson and members are selected by a high-level committee headed by the Prime Minister, and comprising of the Lok Sabha Speaker, the Union home minister, the leader of opposition in the Lok Sabha, leader of opposition in the Rajya Sabha and the deputy chairman of the Rajya Sabha.

Also read: The report on Kashmir by UNHRC had no relation with the UN: V.K. Singh

However, since the age of retirement for an SC judge is 65, only a small pool of two-three retired CJIs are available to head the NHRC at any given time. Even then, many of the appointments made by the government have received flak.

Current NHRC chairperson Dattu does not have a great track record with regard to human rights in his tenure as the CJI and an SC judge.

Apart from confirming a record number of death penalties (second highest for any SC judge), Dattu had also refused to review the apex court’s controversial 2012 verdict that upheld the colonial provisions criminalising homosexuality.

Its previous chairperson, K.G. Balakrishnan, was accused of corruption and a case seeking his removal was pending in SC while he was heading NHRC.

The appointment of former SC judge Cyriac Joseph as an NHRC member in 2013 was openly criticised by then attorney general Mukul Rohatgi in court. Rohatgi said Joseph, whose term has since ended, had made it to the NHRC despite his track record in SC where he “wrote just seven judgments in three years”.

Union ministers Arun Jaitley and Sushma Swaraj, who were then in opposition, had also questioned Joseph’s appointment.

But the Narendra Modi government too has been slammed for its choices. In 2016, it informally approved the appointment of BJP vice president Avinash Rai Khanna as an NHRC member.

It was seen as the first time that a political appointee had been recommended for the post. When the proposal was challenged before Supreme Court, however, Khanna declined to accept the position.

The commission has also received flak over the lack of diversity in its members.

In February 2017, in a major embarrassment to India, the UN body GANHRI deferred NHRC’s re-accreditation until November 2017. In its report, recommending deferment, GANHRI noted the Commission’s failure in ensuring gender balance and pluralism in its staff and lack of transparency in selecting its members among other reasons.

In February 2018, though, NHRC retained its ‘A’ grade from GANHRI.

In its favour, the rights body has been pushing for an amendment to the act to change the criteria from CJI to former SC judge for its chairperson and to mandatorily include women members in the five-member commission.

State commissions

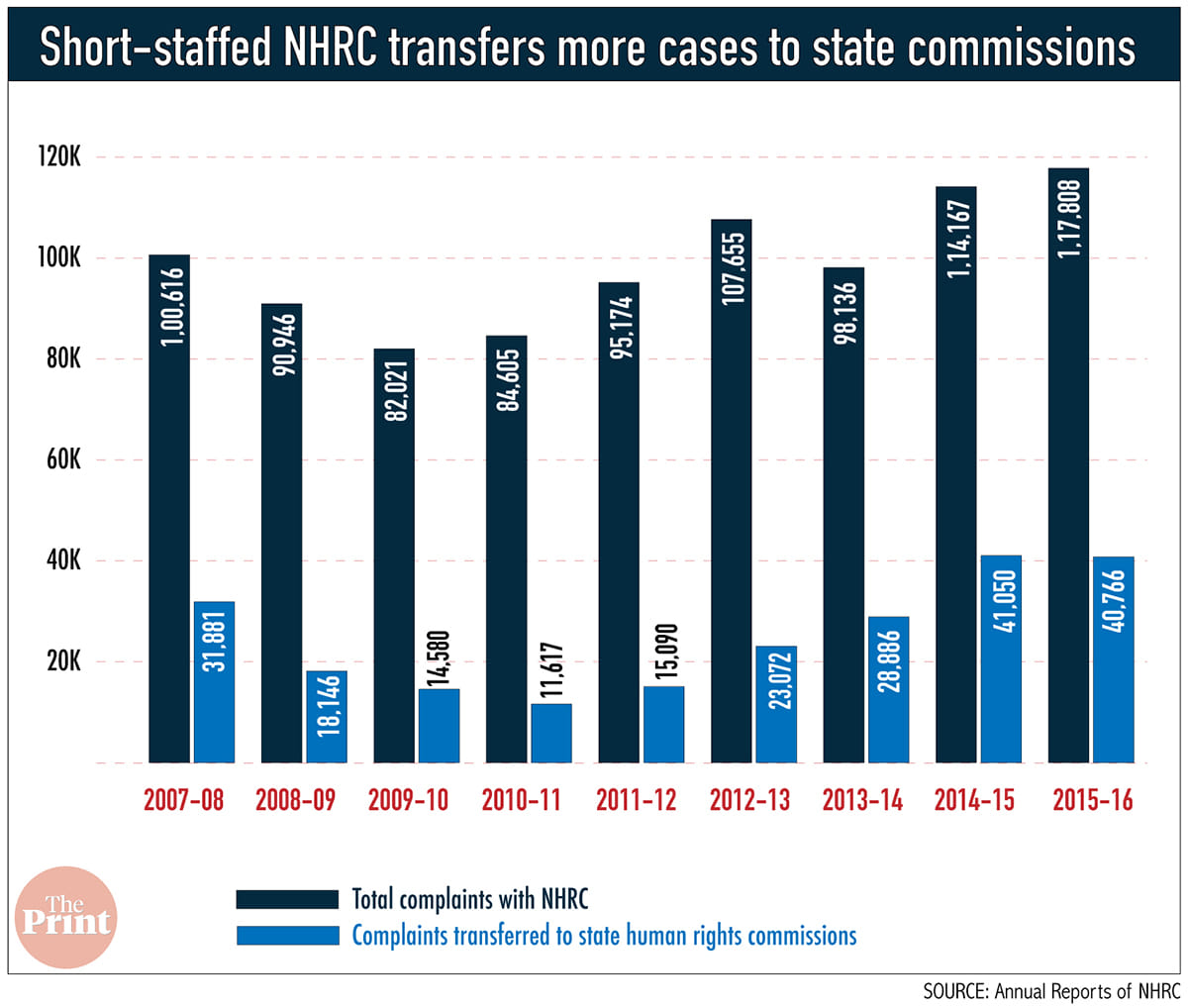

The NHRC is also the nodal body for the state human rights commissions and has the powers to refer some of its cases to the state bodies.

From 2015 to 2016, the number of cases the NHRC referred to state commissions across the country saw a 340 per cent jump, from 7,193 to 24,622.

The lower numbers in previous years is because many states had not set up commissions till as late as 2013. In 2011, according to a Home Ministry response to Parliament, eight states had not set up commissions by then.

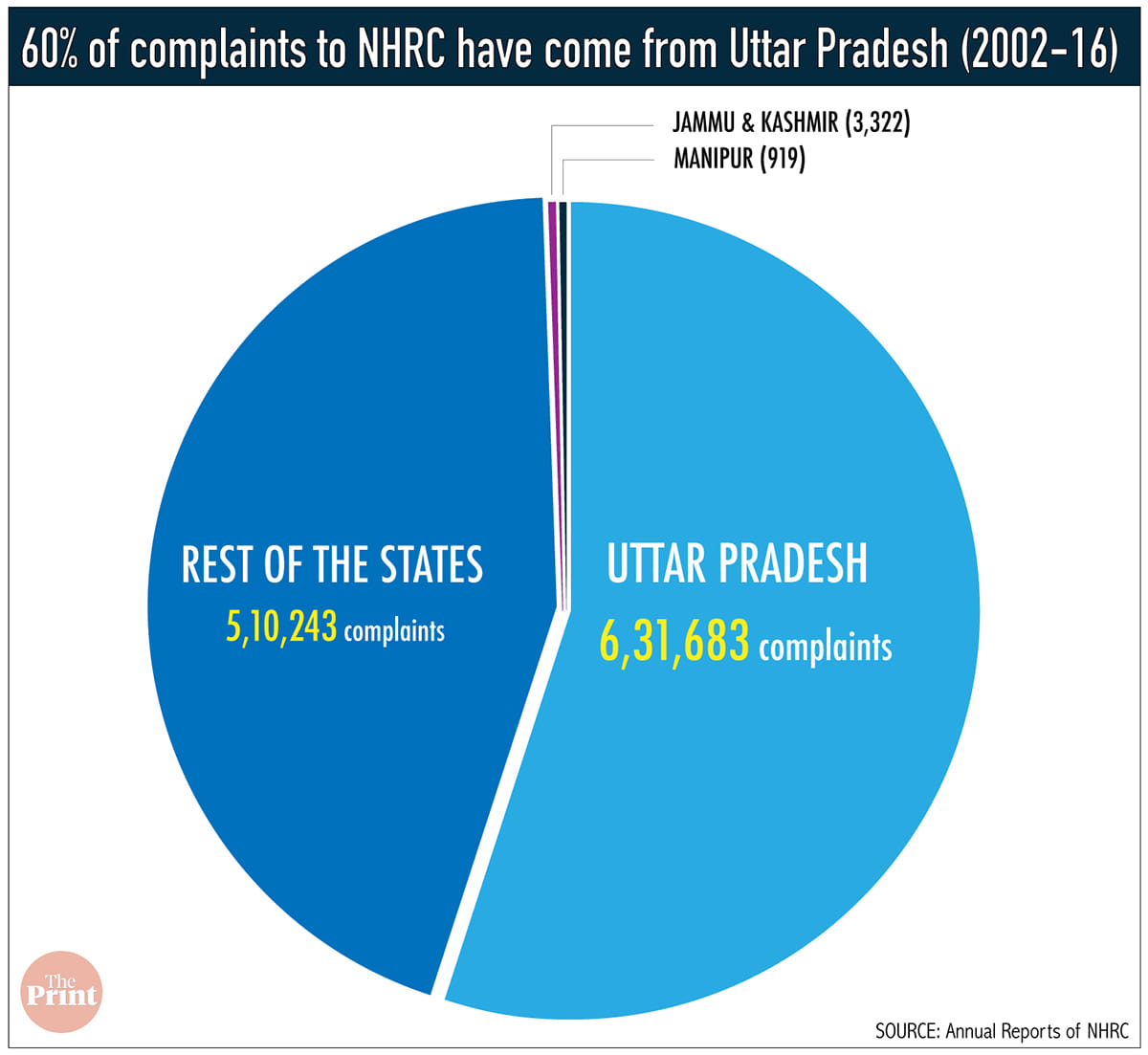

A striking aspect, however, is the inordinate attention that the Commission pays to Uttar Pradesh. Nearly half of the country’s rights violations come from that state.

But despite allocating half of its resources exclusively to Uttar Pradesh, the Commission has not made much headway with the present Yogi Adityanath government.

In focus, Uttar Pradesh

Since the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power in 2017, Uttar Pradesh has witnessed more than 1,900 police ‘encounters’, resulting in over 50 deaths. The Adityanath government has received over 25 notices from the NHRC since March 2017 but only three pertain to the encounter killings.

In October 2017, the NHRC took suo motu cognisance of media reports about the killing of an alleged gangster, Sumit Gurjar, in an encounter by police in Greater Noida, just two days after the incident occurred.

A month later, the Commission once again took suo motu cognisance of Chief Minister Adityanath’s endorsement of the encounter killings.

In February, the commission took suo motu cognisance of another case in which a Noida policeman allegedly shot a 25-year-old gym trainer to earn an out of turn promotion by claiming an ‘encounter’.

Sources told ThePrint that the UP government has filed a joint reply for all three encounter-related notices, which the Commission is currently examining.

Other complaints range from the state not providing ambulances, custodial rape to police allegedly seeking sexual favours from a rape survivor before taking action against her.

, 2015 have stated, “to check the brutal use of power against innocent people brought to a police station, IT IS MANDATORY FOR POLICE STATIONS TO INSTALL CCTV CAMERAS”.

☆That the custodial torture of Zamir Ahmed Khan UP (case No. 14071/24/2001-2002) SHO-abused his power. “Because there is/was no serious injury caused to victim is disturbing. Custodial torture even without inflicting any visible injury would justify award of compensation and disciplinary action against delinquent police personnel.” NHRC.

☆Supreme Court of India has termed custodial torture as a “naked violation of human dignity that destroys victim’s self esteem and termed this inhuman treatment as a calculated assault on human dignity. An accused or suspect cannot be tortured or subject to third degree torture or be eliminated.” Justice Kuldeep Singh, Justice A.S. Anand, Justice VR Krishna Iyer of Supreme Court of India.

☆In Kishore Singh Vs State of Rajasthan, the Supreme Court of India observed, “to resort to third degree methods by police violates Article 21 of the Constitution. The police rely on fists than on wits, on torture more than on culture and the police by doing such acts cannot control crimes. Nothing is more cowardly- unconscionable than a person in police custody beaten up” (1981-SCR(1)1995).

☆Supreme Court of India Judgment in Joginder Kumar Vs State of UP on 25 April 1994, Equivalent Citations: 1994 AIR 1349, 1994 SCC (4) 260, Author: M Venkatachalliah, Justice S. Mohan.

☆ Sheela Barse case imposed upon the Duty Magistrate, to enquire from the person brought to them whether he has any complaint of torture or maltreatment?

☆ NILABATI BEHRA VS STATE OF ORISSA gives RIGHTS OF COMPENSATION.

☆ In D.K. BASU VERSUS STATE OF WEST BENGAL, SUPREME COURT OF INDIA HAS DIRECTED THAT, it was to be entered in daily diary as to who of the detainees family /friend is informed ? Supreme Court had stated that merely on the suspicion of the complicity in an offence, a person cannot be arrested.”No arrest can be made because it is lawful for the police officer to do so. Except in heinous offences, and arrest must be avoided.The rights of a citizen of Article 21 and 22(1) has to be scrupulously protected.”

☆ Further the Indian Police Act in Section 7 & SECTION 29 clearly states, “Torture in custody is a punishable act.”

☆ In Khatri Vs. State of Bihar the Supreme Court of India gave rights to legal and medical assistance

☆Article 20(3), 21, 22, 32 and 226 of the Constitution give protection to the human rights. The NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION prohibits custodial torture of any kind: mental or physical and has directed the SHO’S of all police stations to keep the suspects, “safe from any physical assault while in police custody”.

☆Article 9(5) gives ENFORCEABLE RIGHT TO COMPENSATION.

☆Rule 16. 17 ” (Ditto of PPR) DEALS WITH POWER TO SUSPEND.

RULE 16.18 DEALS WITH SUSPENSION DURING A DEPARTMENTAL ENQUIRY

Given its constraints in terms of staff and resources, perhaps the NHRC ought to focus more on quality than sheer numbers. The almost daily reports of encounters in the badlands of Uttar Pradesh call for a robust intervention. It should make its presence felt by fewer, sharp interventions.