New Delhi: A Lahore-based engineer-turned-sociology professor has done something Pakistan hasn’t seen since Partition: he’s brought Sanskrit back as a field of study. He says he wants to understand the “soul of South Asia.”

“Classical languages carry our collective wisdom. Learning them is a moral project, a project of humanity,” Shahid Rasheed, associate professor of sociology at Forman Christian College, told ThePrint.

What started as a passion project has grown into what has been described as a “renaissance of Sanskrit in Lahore”, starting with workshops and growing into a full course at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS).

For 52-year-old Rasheed, language is ‘a bridge’. It is a shared history and it begins at home. His first student was his daughter, who is now fluent in Devanagari script.

He traces his ancestry back to a village in Karnal, and one of his grandmothers came from Sheikhpura in Uttar Pradesh. These links, for him, are reminders of a shared civilisational landscape fractured by borders, politics, and history.

But building that bridge through Sanskrit wasn’t easy in a country with no teachers and almost no trace of the language.

Also Read: Dhurandhar opens Pakistan vs Pakistan debate. Baloch are split, Karachi journalists divided

‘Devanagari is profound, artistic’

Rasheed has always had a keen interest in languages, but he encountered Sanskrit by chance. Fifteen years ago, he stumbled upon a book titled Self-Teach Sanskrit. For years it sat on his shelf, unopened. Until one day he began reading it.

“Devanagari attracted me. It is so artistic, I found it profound,” he recalled.

Once he mastered the script, Sanskrit no longer felt unreachable — only daunting. But there were no books or resources on Sanskrit in Pakistan. No books in libraries. Teachers warned him it was too difficult.

And so, Rasheed improvised. He found guides where he could: a Sanskrit professor in Australia, online platforms in the United States, YouTube channels run by Indian NGOs.

“I asked anyone traveling abroad to bring me Sanskrit books,” he said. “Now I have a full shelf.”

From passion to pedagogy

Once he had acquired some mastery over Sanskrit, Rasheed acted on his instinct that other Pakistanis wanted to learn the classical language too.

That theory proved right when his workshops in Lahore drew in students from computer science, business, and the humanities.

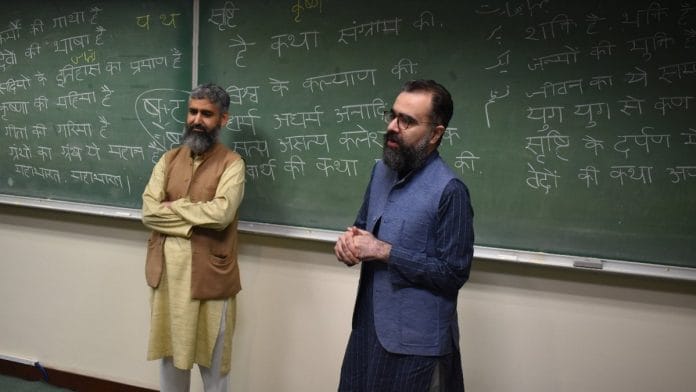

Soon, a longtime acquaintance took notice: historian Ali Usman Qasmi of LUMS, one of Pakistan’s most prominent universities. Qasmi had been searching for someone to expand language offerings under the “Heritage at LUMS” initiative. When he discovered that Rasheed had been teaching himself Sanskrit — and excelling — he reached out.

“We were incredibly lucky,” Qasmi said. LUMS already offered Punjabi, Balochi, Pashto, Sindhi, and Arabic and Persian. But Qasmi asked, “what about others like local Indian languages or classical Indian languages?”

At the Gurmani Centre for Languages and Literature at LUMS, Rasheed first ran a Hindi workshop, then a four-month Sanskrit programme, and this year a full university-level introductory course, one of the first of its kind in Pakistan.

Also Read: Pakistani activist couple indicted for criticising the military. Citizens hit the streets

‘A 100% satisfaction’

For Qasmi, the case for offering Sanskrit in Pakistan is both academic and philosophical. The humanities departments at leading American universities regularly train students in classical languages.

“So much of Pakistan’s philosophical traditions go back to the Vedic age,” he said. “Sanskrit is key to understanding our own cultural and religious landscape.”

Rasheed’s first full semester-long course, Introduction to Sanskrit, concluded only weeks ago. Enrollment was small, around seven or eight students, but the commitment was deep.

“All of them want to continue to level two,” Rasheed said. “A hundred percent satisfaction.”

Still, cost remains a barrier. Fees at LUMS are high, and while the university opened the course to non-enrolled students, many could not afford it. Interest, Qasmi insists, is not the problem; access is.

Over time, he hopes the university will build a stable enough student base to support year-long courses and even advanced instruction that would allow graduate students to engage directly with classical texts such as the Mahabharata, Upanishads, and Vedas.

“That is the ambition,” he said.

The implications, he asserts, are larger than scholarship.

“In ten or fifteen years, we may have a new generation of Pakistani scholars working on these texts,” Qasmi said.

Such intellectual cross-pollination, he argued, could shift regional perceptions. “It will dispel a lot of misconceptions in India about Pakistan. People will realise that this is shared heritage, shared knowledge.”

Rasheed agrees. He speaks of Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian not as relics but as tools. Learning another language, he said, is a way to “step into someone else’s shoes.”

Classical languages, especially, reveal continuities obscured by modern politics, including shared stories, shared metaphors, shared wisdom passing across centuries.

Rasheed gave the example of the dual noun. His Arabic teachers once told him that Arabic’s capacity to express singular, dual, and plural forms was unique. Later, a Sanskrit instructor said the same of Sanskrit.

“Every language thinks it is exceptional,” he laughed. “But when you learn multiple languages, you see the world through many lenses. You break that ethnocentrism.”

His long-term goal now is to write the first comprehensive Sanskrit grammar in Urdu—three volumes, he predicts, the first of which he has already begun drafting. “It will take me a few years,” he said. “But this is my life’s project.”

Rasheed weighed in on the improbability of it all.

“I never imagined people in India would take interest in this,” he said. “But language does create bridges.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

What days. Educated Pakistanis can consider Sanskrit and Sanatana the ‘soul of South Asia’, find Devanagari ‘so artistic [and] profound’, but Bharatiya mullah maulana class will forever deem it haram and even try hard to speak an Urdu without any Bharatiya traces (though it’s impossible).

Anyway happy to see the part of the world I am from embracing its heritage. Let’s hope for a Sanskritic revival and (inshallah) in the future, a Dharmic renaissance.