Mumbai, Delhi: IIT Bombay students lurk around the campus looking for empty labs, shady trees and deserted streets. They meet not for romantic rendezvous; they are the members of Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle. It’s at these meetings that they discuss incidents of caste harassment on campus and brainstorm ways to combat it.

But they say they are finding it increasingly difficult to meet in groups and don’t want to be subjected to the savarna gaze.

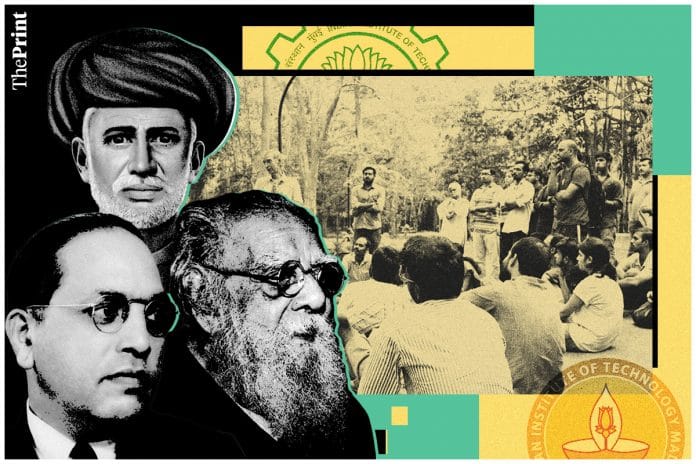

The Ambedkar-Periyar-Phule collectives on IIT campuses is a recent phenomenon in India’s prestigious, globally known engineering colleges. For long, the Indian Institutes of Technology have been the preserve of historically dominant caste groups. And Dalits, OBCs and Tribal students have suffered daily casual casteism, discrimination, offensive language and stigma.

Students from marginalised groups who used to dream being part of these big campuses now weep secretly in the bathrooms of these buildings. Scared, angry and sad, their biggest battle is to just belong in these haloed institutions.

This is where student organisations like APPSC and Ambedkarite Students Collective (ASC) step in. They help marginalised students cope with the systemic discrimination they face both inside and outside the classroom.

On February 12, this discrimination once again made national headlines when an 18-year-old IIT-Bombay student named Darshan Solanki from Gujarat’s Ahmedabad allegedly jumped off from the seventh floor of the campus building. About three weeks later, family of Solanki and other Dalit students who are similarly “victims of institutional murders” gathered at Mumbai’s Azad Maidan for a protest, which was covered in a film titled There is no caste discrimination in IITs? by Maharashtra-based documentary filmmaker Somnath Waghmare. Giving a speech at the gathering, Darshan’s father Ramesh Solanki broke down recounting his son’s enthusiasm for joining the IIT-Bombay and his interaction with the institute after the death.

“They told us that Darshan had fallen from the seventh floor of a building. The ground under our foot was shaken. What do we do? I had entrusted my son to the IIT people. My dreams were entrusted to the IIT. I sent my boy, my flower, thinking they will turn him into a plant. Instead, they crushed my flower and threw him away,” Ramesh said.

A month and a half after Solanki’s death, which has shone the light on IITs’ increasing caste divide, the Mumbai police registered an FIR under SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and charged “unknown people” with abetment to suicide under IPC Section 306. Since 2018, thirty-three students have died by suicide at different IITs, according to the Ministry of Education data presented in the Rajya Sabha recently. Almost half of them are from the SC, ST, and OBC communities. Moreover, according to Union Minister of State for Education Subhas Sarkar, between 2018 and 2023, more than 19,000 SC/ST/OBC students dropped out of IITs, IIMs, and central universities. All this has led to more organising by the groups to counter casteism – the latest one at IIT-Goa. Of the 23 IITs, five now have functional Dalit students collectives.

“We give them the space, support, and sometimes solutions. We are fighting for the bare minimum on this campus. To just be, like others,” says a member of ASC who did not want to be identified. The member is a PhD student at IIT-Delhi, where an SC/ST Students Cell was formed just six months ago. Its members still speak in hushed whispers and are self-conscious about drawing too much attention.

Also read: Erasure of caste in universities existed during colonialism, but its roots much deeper

Every small step is a giant struggle

It’s still early days. The IIT Ambedkar study circles are nowhere near the strident student activism of JNU, Jamia Millia, and Delhi University. Most students said they don’t find any accessible, approachable platforms to air their complaints. So, the first thing that the Ambedkar study circles do is to begin organising fortnightly meetings, lectures and workshops on caste harassment.

The older collectives, like APPSC of IIT-Bombay, are more active. From holding events and festivals to putting up poster campaigns, they have been upping their sustained visibility. But the administration, many members say, are more a barrier than an empathetic facilitator.

More often than not, every tiny step forward and every little action comes after an exhaustive fight against the dominant tide of rejection.

“We put up posters and other students tear them down. They do it again and again,” said Mohit*, who is associated with APPSC at IIT-Bombay.

APPSC at IIT-Bombay was formed in May 2015—after IIT-Madras banned APSC—to not just help Dalit students with their grievances and give them a sense of belonging, but also, as Mohit puts it, “to question the campus, so voices can be heard.”

The collective often holds workshops on “caste sanitisation”, and invites lecturers as well. It hosts events in public spaces, near hostels where freshers reside.

“Sometimes, we get opposite opinions. Bullying used to happen, but still we manage to hold these discussions,” Mohit adds.

Today, IIT-Bombay APPSC has around 500 members. But it is not a recognised body. This is used as an excuse to stop members from organising events, says Mohit.

“It’s why we face a lot of issues even when putting up a poster. Our existence is the problem for them. Even teachers who try to help us get threatened by other teachers and the administration.”

ThePrint reached out to IIT-Bombay by email. The story will be updated with their response.

“We exist without permission,” says Mohit.

Also read: Education is the only way ahead but SC/ST/OBC students trapped in status quo of merit

Watching out for each other

At a recent APSC meeting in IIT-Delhi, a first year BTech student got up and conflated his inability to fit in with his intelligence.

“Perhaps our intelligence level is low,” he said.

From the highs of getting into one of the most elite institutes, this was a low he never thought he would experience.

Senior students listened and tried to assure him, but to no avail.

“This thing has been filled in his mind in such a way that even after explaining many times, I have not been able to make him understand that he is wrong,” says a final-year PhD student of IIT-Delhi in frustration.

Senior APPSC members across campuses take it upon themselves to shepherd new Dalit students, most of whom are not prepared for the reality of life on campus – from caste slurs to name calling to being made to feel less.

Organisations hold regular meetings where older students listen and try to counsel their juniors. But most of the time, students are hesitant to speak up in a public forum. They fear backlash.

“It takes time—4 to 5 meetings—before trust is built. But some just cannot gather the courage to come out,” says another member of APPSC, IIT-Delhi.

Last September, the ASC member cited above screened Nagraj Manjule’s Marathi film Fandry on campus. It’s the story of a Dalit boy from a butcher’s family who falls in love with a classmate from a dominant caste. More than a hundred students gathered to watch the film. Powerful scenes—like the one where the boy and his family carry a trussed-up dead pig and walk past the photo of BR Ambedkar in his trademark blue suit staring at them—galvanised the audience.

After the screening, many people went on stage and shared their experiences and spoke about systemic discrimination.

“We try to ensure that new kids have a platform to talk about the way they are treated,” the ASC member said.

For first-year MTech student Akash from IIT-Delhi, the ASC is family. “Those with whom we have lived can understand our pain,” he says.

Going to IIT was his father’s dream, one that Akash is proud to have fulfilled. Back home in Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, he is a hero. But his reality in Delhi is fraught with slights and stress. He’s been taking medicine for migraine attacks over the last month. His one solace is the ASC meetings.

The discrimination he faces is not specific, but is visible in small interactions that the privileged take for granted. He finds himself excluded from groups. He’s taunted, but in a way that is made to seem like a harmless joke, one that he can’t fight against. Most of his classmates are from dominant caste groups.

“I tried to fit in, but I failed.”

Since he joined the ASC in September, Akash found some relief in the shared experience of others.

“Our caste is our identity, we cannot run away from it no matter how much we want. When I saw Babasaheb Ambedkar’s poster displayed on ASC’s stall on the IIT campus, I felt that someone like me was visible in the crowd. So I went and joined them,” he says.

Dalit student organisations regularly raise issues of fee hikes, caste discrimination, and recruitment of SC/ST students in PhD programmes.

An RTI application filed in March 2021 found that IIT-Bombay had only 305 students from SC category and 60 from ST category out of total 3,534 PhD students — a mere 8.63 per cent and 1.7 per cent composition. Unlike for BTech programmes, admission to PhD programmes are heavily decided by faculty interventions.

Also Read: More Dalit students going to Oxfords, Harvards. West now gets the caste divide

Not on the same level as LGBTQ

There is also some envy when the Ambedkar-Periyar-Phule collectives compare their activism with LGBTQIA groups in colleges. Some students say that there have been cases when campus queer collectives get recognition faster than Dalit student groups.

In IIT-Bombay, the queer collective ‘Saathi’ applied for recognition in 2016, at the same time the APPSC also submitted its application.

Saathi was formalised in 2018, while APPSC is still waiting to hear from the administration.

“We neither got a reply nor any feedback. They haven’t rejected our application, but they haven’t answered it either,” said Mohit.

At IIT-Delhi, the queer collective Indradhanush has been formalised. The APSC was recognised by the administration in March 2023 but it is yet to be formalised.

“Baby steps,” says the ASC member.

“We work together with the queer collective, their struggle is no less than ours.” But the student has observed how in IITs, at least in Delhi, more “LGBTQ people are coming out in the open”, and embracing their identity publicly. “The administration, too, has been accepting of them. But most SC/ST students in IIT-Delhi don’t want to reveal their identity openly.”

Recognition by the administration is key because it opens up funds, facilitates organising events and helps students prepare their portfolio for job applications.

“Our biggest fight is for our belonging and being,” says the ASC member. “If we walk on the campus wearing Ambedkar’s badge, people comment with remarks ‘their politics has started’. For us, it is our being, for them it is politics.”

The SC/ST cells set up in the institutions, which include Dalit, Tribal and OBC faculty, are only in name and rarely receive complaints.

Also Read: 98% of faculty at top 5 IITs are upper-caste, reservation not implemented, says Nature article

Before Solanki, there was Ambhore

The IIT-Bombay committee formed to probe Darshan Solanki’s suicide concluded that only his sister’s statement corroborates caste-based discrimination, and that there is no other specific evidence.

But more than a month after Solanki allegedly ended his life on 12 February, the SIT investigating the case recovered a ‘suicide note’ on Monday (March 27). It was found in Solanki’s hostel room, and according to the police named a batchmate.

Students of IIT-Bombay allege that whenever a suicide is reported on campus, the administration does not openly share the information with the students. Even in Solanki’s case, the matter of caste discrimination came to light only after his full name was revealed, says a student.

“There are so many incidents of suicide that are not probed from the SC/ST angle,” Mohit says. He cited the death of Aniket Ambhore in September 2014 as a case in point.

Ambhore, a fourth-year electrical engineering student, fell from the sixth floor of his hostel building. The death was first framed as an accident, then ruled an outcome of the student “battling internal contradictions” by a three-member committee — all professors of IIT-Bombay — formed by the institute to probe the alleged suicide. The probe itself was ordered only after Ambhore’s parents wrote to the IIT director. The committee did make a general observation about prevailing caste discrimination on the campus, while noting “one case” of a visiting faculty passing a casteist remark in a communication skills class.

After Solanki’s death, Ambhore’s parents spoke out against caste discrimination in IIT-Bombay.

“We are still asking the administration to exemplify the suggestions that the AK Suresh committee had recommended. But there is no response from them,” says Mohit. Among other things, the committee had suggested forming a “diversity cell”, sensitisation programmes for faculties and looking out for promising SC/ST students for career encouragement.

“There is not much mental health support for us. Whatever it is, is also casteist, shallow, and many times counterproductive to students who need help,” says Mohit.

An APPSC member recounted the traumatic experience of a student who had visited the campus counsellor. “The counsellor made him feel that he was not intelligent enough and said, ‘I don’t think you can handle this’.”

Most of the students ThePrint spoke to say that the faculty and administration should step in to provide a support system for students who are struggling to cope.

“If you think there is a lack of intelligence, you can create some mechanism for this on campus. A few extra classes, and an English teacher who could help them,” says Ali, a member of APSC, IIT-Delhi. This was one of the recommendations that the Suresh committee had made in its report on Ambhore’s death.

Also read: EWS quota will finally destigmatise caste reservation in India

Casteist slurs and ‘jokes’

Suicides are alarming and grab headlines across the national media, but what goes unnoticed and unreported are daily micro-aggressions.

The first question on campus usually is: ‘What is your rank?’ It may appear to be a routine question, but it is a socially coded question and often has caste fallout. People make friends and judge each other. A student studying BTech at IIT-Delhi said that even professors ask this question openly in the classroom.

“If my [JEE] rank is 445 and I got textile, then people understand that I got in on the general category. But if my rank is 1,000 and then my branch is textile, then their facial expressions change,” says a BTech student from IIT-Delhi.

This is not limited to classrooms, but pervades student hostels and cafeterias. It defines interactions between students and how social groups are formed. Some students who feel forced to hide their caste have to face another set of problems. They have to listen to their dominant caste friends complain about students who got a seat in the SC/ST category.

“I hid my caste for a long time, so many of my friends used to share their thoughts with me. They say things like, ‘That rascal got admission through reservation and got a better branch than me, while my rank is higher than him’,” says Rohit, a first-year student from IIT-Delhi.

Some students use offensive words like ‘chamar’ but immediately pretend as if they don’t know what it means when they are called out.

But there are no complaints of such incidents. Students are afraid that if they complain, they would be branded and more harassment would follow.

“Everything cannot be proved with evidence. In cases where there is evidence, action is not taken,” says Himanshu, a PhD student from IIT-Delhi.

A newly formed group of 30 called ‘Student Federation of Dravidians’ was launched on March 18, and hopes to help Dalit student collectives across Indian campuses.

“We will work to help Dalit students by giving them political backup, legal help, and constitutional support. Students across the country are joining us and gradually our organisation will grow bigger,” a member Alyakumar says.

Students that ThePrint spoke to talked about how students from the dominant caste groups openly discussed their second names or made caste-related ‘jokes’.

One Dalit student said that the cafeteria of IIT-Bombay hostel has a separate section just for students from the Jain community.

“Their utensils are also kept separately,” says the student. “Once a new student sat there with an egg, and there was a lot of uproar.” The administration has denied this.

A student from the Jain community that ThePrint spoke to claimed there was no such demarcation. “No place is fixed but we like it here so we sit here,” he said.

Back in the campus, Mohit and other members of the APPSC in IIT-Bombay are planning their next event. Posters and pamphlets are likely to be pulled out or torn up.

When all else fails, he and others will stand together holding the posters in their hands.

“They can tear down the posters, not us.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the students.

(Edited by Prashant)