Delhi: Against the setting sun glistening in the luminous lake, teenage boys pose for Instagram photos and reels. This is Delhi, a city not really known for its rich scenic Reels potential. But there has been a quiet, under-the-radar move to liven up neglected, far-flung Delhi neighbourhoods with lakes.

Till about a year ago, this land in Sanoth village in north-west Delhi’s outskirts, surrounded by Bawana industrial area and resettlement colonies, was nothing more than a dirty puddle. It was only used during Chatth puja. Then the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) brought its earth diggers to the site. The puddle was dug deeper and wider, walls were erected around the property, the land was levelled, and a lake emerged. Today, the wasteland is an ecological hub.

Under the Delhi Government’s ambitious City of Lakes project, Sanoth got its first-ever artificial lake. It is filled with recycled water from the nearby Bawana Common Effluent Treatment Plant (CETP). The land around it has swings, an open gym, and an amphitheatre, which is open to the public for free.

Delhi Jal Board aims to transform the Indian capital, globally infamous for toxic air, into a city of lakes. It has given Delhi 14 new lakes and 35 water bodies over a span of five-six years in neighbourhoods such as Sanoth, Pappankala, Rajokri, Burari and Bhalaswa, among others. Next, they are moving to Naraina and Rohini and a few other nearby areas. Ankit Srivastava, the engineer who is working on this drive says 265 lakes and water bodies are being rejuvenated. Putrefying dump yards are now scenic landscapes. Apart from improving the aesthetics of the city and reviving public spaces, the project is increasing water tables and bringing birds back too.

And for the people living in congested clusters nearby, the lakes and the parks around them are recreational spots.

“We come here to take respite from home. The lake is beautiful and the garden gives us a very good view. We take photos here,” says Krishna Raikwar, a school student living near the Sanoth lake complex.

Also read: ‘Beautification’ to bulldozers, how Delhi is going all out to become showcase city for G20 summit

Beyond beautification

There is a bigger goal behind Delhi’s City of Lakes project. And it goes beyond beautifying the city. The Delhi government engineers and fellows working on these projects told ThePrint that within a few years, the city will be self-sufficient in its drinking water needs.

“The rate at which the water is reviving, Delhi will soon stop depending on other states for its drinking water needs. In the next step, tube wells will be installed and the percolated groundwater can be processed and used for the supply of drinking water,” says Ankit Srivastava, consultant, hydraulics and waterbody, DJB.

In 2016, the crucial Munak canal in Haryana supplying 60 to 70 per cent of Delhi’s drinking water was broken down by agitators from the Jat community, who were demanding caste-based reservation. Water supply to more than seven lakh households was affected.

The crisis exposed how vulnerable Delhi’s drinking water supply channels are to external forces. It added momentum to the lakes project. In the corridors of the state secretariat land was being identified and maps were being drawn to make the city self-sustainable in its water needs.

“We identified around 1,000 water bodies in the city. But most of these natural water reservoirs had either become dumping grounds of solid waste or were encroached and neglected,” says Srivastava.

The concretisation of the city had eroded the catchment area of the lakes and the aquifers had depleted up to 30 meters in three decades. With a budget of Rs 376 crore, the Delhi Jal Board started the task of bringing alive 159 water bodies initially to replenish groundwater. The project has since expanded to take bigger lakes under its ambit.

Two such lakes are changing the shape of Dwarka.

Also read: Nagaland loves grand white weddings. It isn’t looking to rest of India for inspiration

New home to birds

Dwarka’s sewage treatment plant (STP) in sector 16, surrounded by three universities and high-rise residential complexes, is an eyesore in the region. The huge machines clean the solid waste from the area of all physical, chemical and biological impurities but that treated water is pushed back into the clogged Najafgarh drain flowing nearby and ultimately joins Yamuna River.

But last year, the students in the campuses around STP started noticing birds who had made the undisturbed floating wetlands in the lakes their nesting beds. These birds were not native to Dwarka.

“My students informed me that a lake has come up in the STP complex. Since 2010, I have identified around 120 species of birds in this region, none of them are waterbirds. In the last two years, we are also seeing a constant rise in the number of waterbirds like spot-billed ducks, red-naped ibis, white-breasted waterhens, cormorants, Indian cormorants, medium egrets, cattle egrets, little egrets, black-crowned night herons, ponderons.We have noticed their breeding population here,” says Sumit Dookia, assistant professor at the school of environment management, Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University.

Inside the lakes, automatically-operated aerators maintain dissolved oxygen in the water, which helps in the natural cleaning. Floating wetlands and the plants on them absorb pollutants, including phosphate, which is mostly found in detergents. Islands created around the existing trees in the lake add to the scenic beauty and protect the wetland birds from predators.

For nature lovers, this ecological marvel has had a ripple effect.

“A wetland creates a niche of wetland-loving birds in an urban area. Now that they have an undisturbed habitat, their numbers will surely increase,” adds Dookia.

Recharging groundwater

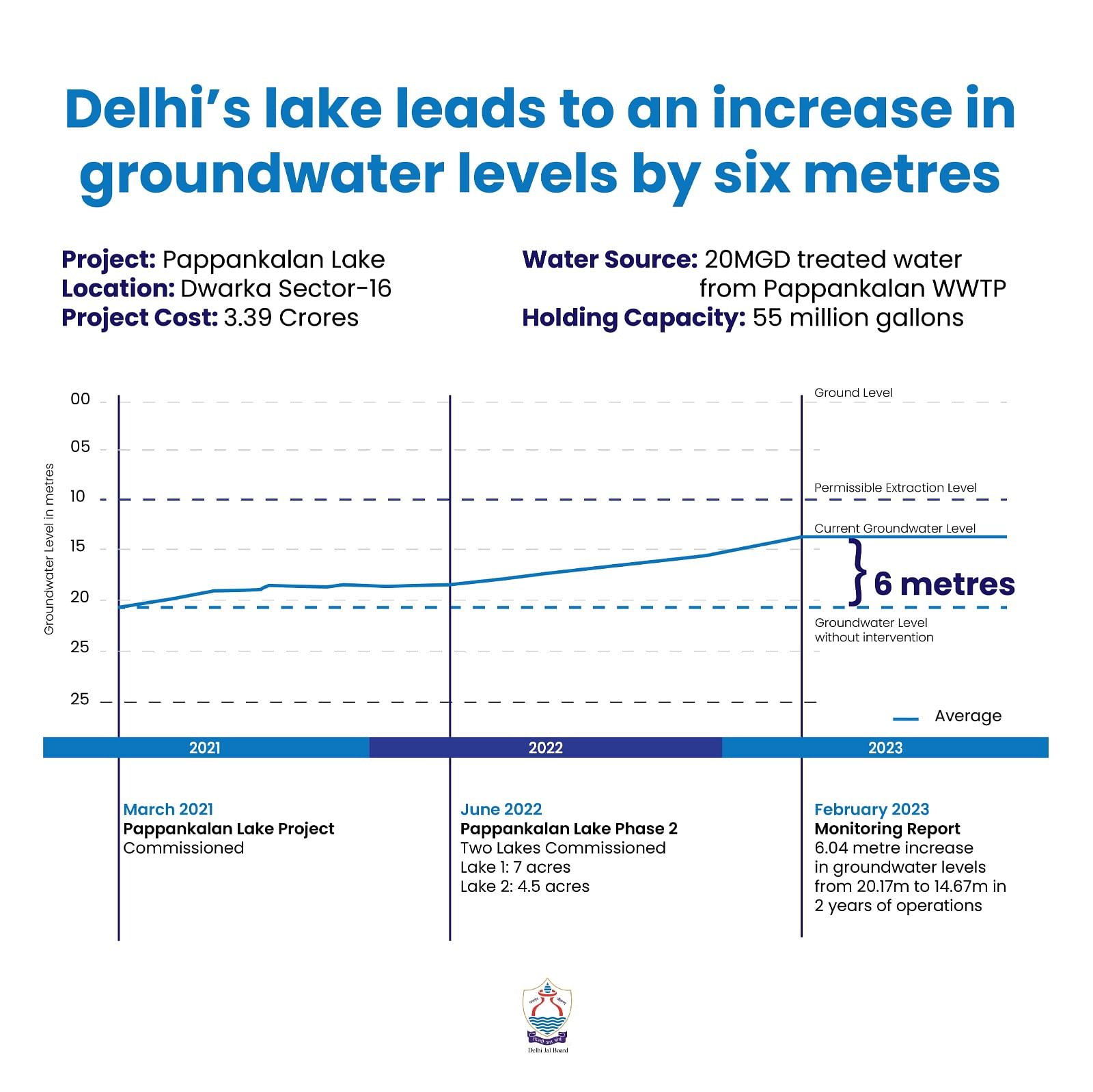

The silent transformation of the unused 11.5-acre land inside the STP showed results. Locked from the public, about a year ago, the land was cleaned, dug and stone pitched to create two big lakes, called Pappankala lakes 1 and 2, which can hold 55 million gallons of water. Instead of throwing the recycled water back into the Najafgarh drain, it was diverted to fill these lakes. Within a year, the water table in the region rose exceptionally high.

“Despite massive use of the groundwater in the area, the groundwater level rose to 5.5 metres in eight to nine months in this region. This is happening because we are continuously putting clean water into the lake. And the soil base is porous, so 10 to 15 per cent of the water percolates into the ground,” says Ashish Yadav, fellow at the DJB for the City of Lakes project.

According to the Central Ground Water Board, if extraction of water stops and rainwater is the only method of recharge, then the water table in the region will rises to one metre in a decade.

The lake is now visible from Delhi to Mumbai flights, according to Dookia and Srivastava. The area’s transformation from barren land to a big water body can also be tracked on Google images.

Moving a step further, now the land around the lakes will be levelled and beautified. After cordoning off the area from the STP, the lake will open to the public. Two more lakes— in Najafgarh and Dwarka— are nearing completion and will soon guzzle up the remaining treated water from the STP, the DJB engineers say.

“More and more treated water is now used to recharge groundwater. This means that less treated water now flows into the Najafgarh drain,” says Srivastava.

Also read: Hard-won gutka ban is now under threat. This time from courts

Public demand

The revival of lakes and water bodies such as Sanoth, Pappankala, Rajokri, and Burari, among others has flooded the DJB with requests from people to rejuvenate lakes in their areas. Based on such requests, the DJB is now planning to start work on Naraina’a natural lake.

The lake’s new map has a toy train, amphitheatre, swings, open gym, jogging tracks and kiosks around the 11-acre land. Treated water from the Naraina CETP on the next plot will be transported to the lake which falls between highways, shopping malls and Nariana industrial area. Local people say that the lake will soon become a cultural hub.

“In the 1960s-70s, from rural area Naraina became an urban area. Major residential and industrial areas came up and nobody paid attention to the village waterbodies. The administration did not work on the upkeep of the lake, garbage was dumped here and by the early 2000s, the lake disappeared,” says Aditya Tanwar, president, Rajput Yuva Sangh and a resident of Naraina.

Dirty water from nearby villages and resettlement colonies flows into the low-lying area, where the lake used to be. The river bed is covered with bushes and solid waste, blocking percolation. As a result, the water stagnates and it becomes the perfect breeding ground for insects and mosquitoes in summer.

The residents of the area say that the new lake will also increase the water table in Naraina.

“This area has a shortage of drinking water. If we install water purification facility and supply it, it will help Delhi’s water shortage problem in summers. Reviving the lake will improve the ecosystem of this region. Oxygen level will increase. People will have a place to relax in the mornings and evenings. This place will have boating. Naraina will become alive again,” says Manoj Rajput, a resident of Naraina.

The rejuvenation is at the stage of setting budget estimates and releasing tenders. Every Friday, Naraina residents meet their elected representative, Durgesh Pathak, to give their feedback on the progress made.

“The work on it is happening fast. We have hired consultants and we are making the lake in a way that it remains financially viable. We have a full plan for its maintenance also. We will ensure that it is maintained for 10-20 years. In the coming weeks, we will have the tendering process. And after that, the work will start. This has become a people’s movement that this lake has to be made beautiful,” says Pathak.

Other proposals like Najafgarh, Rohini and Dwarka lakes are also in the DJB pipeline. They all are under construction.

Cooling effect, harvesting, cost cutting

The lakes completed by the DJB show how the local people around it are starting to own them. Lakes and water bodies have also become a part of religious activity for the community. They ensure that the lake is clean and it provides a safe space for families and children.

“The first model we created in Rajokri, people are ensuring that no anti-social activity happens in that area. At some places we found that women harvest the natural grass that grows around the lake for their cattle. That is something we didn’t envisage when we were creating the lake,” says Srivastava.

The DJB also studied the areas around the revived lakes using infrared cameras and found that the lakes are reducing heat in the vicinity. In the peak summer months of May-June, they recorded the ambient temperature around the lake as 5 to 7 degrees lower than the rest of the city’s average temperature.

Using natural means in the lakes’ revival saves money for the state government. Transportation costs of treated water are drastically reduced as most of the lakes are created around the sewage and wastewater treatment plants.

In the next phase of the project, the DJB plans to connect the lakes to the storm water drains, which will prevent urban flooding. Smaller sewage treatment plans are also in the pipeline — all of which will be connected to nearby water bodies where the treated water can be collected.

Also read: Smack & ‘solution’ are consuming Delhi’s homeless kids. For them it’s a refuge

Challenges of rejuvenation

But creating a new water body and reviving an existing one is a task easier said than done. Each piece of land poses a different problem and the rejuvenation plans cannot be replicated.

“Rohini has different soil strata than, say, Bhalaswa. Groundwater is also different in different regions. At Rohini, we have groundwater level of 8 metres but in Dwarka, it is at 20 metres. In some places, the land is clean and we can add water directly. Whereas, in case of Bhalaswa, we had to first divert cow dung coming from the dairy and start the rejuvenation,” explains Srivastava.

In Sanoth and other revived lakes, the properties are guarded against theft of steel and stones from the premises. A security guard keeps the gates locked at Sanoth lake and opens them in the morning and evening only when people start coming in.

Recently, the revenue villages in Delhi were urbanised and have now fallen into the jurisdiction of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). To continue working on the City of Lakes project, the DJB will have to take permission from the DDA. And this may take months to kickstart the projects.

Despite these challenges, the lakes and the parks have something to offer to people from all age groups. And they are aspiring for more.

Young men with selfie sticks and smartphones circle the gate of Sanoth lake in the evening and ask when it will open. This is the only spot in the vicinity with fountains and flowers giving them a beautiful background for YouTube and Instagram videos.

The older men occupy the machines at the open gym.

“This lake gives us space to exercise and get some fresh air. But if they start boating here, it will become even better. The park should have more facilities for old people,” says Jagminder, retired sub-inspector, Delhi police and a resident of Sanoth village.

“And the garden should have flowers like Mughal Gardens,” adds Rajpal Saini, another resident.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)