Insaan kab tak akela jee sakta hai?” (How long can a person live in isolation?), says Salim Mirza, the protagonist of M.S. Sathyu’s Partition classic, Garm Hava.

They are some of the last words in the movie, spoken as Salim finally relents and allows his son to join a protest march, himself joining in a few minutes later.

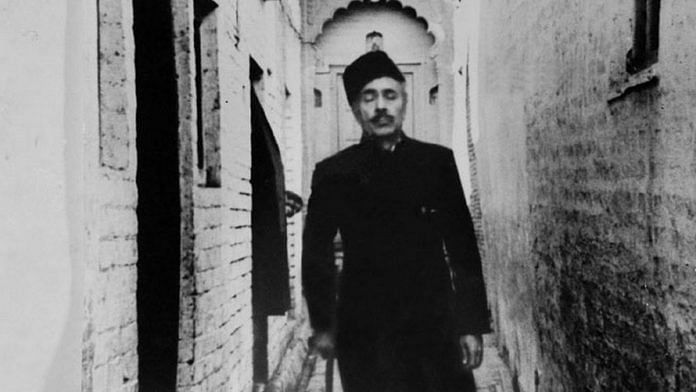

These words were also, in a sense, among the last spoken by Balraj Sahni, the actor who played Salim in the 1973 movie. Sahni died just a day after he finished dubbing for this film. But looking at the events of the past week, one realises that these words are as relevant today.

Set in the time just after Partition, Garm Hava tells the story of a Muslim joint family living in Agra. Salim Mirza runs a shoe making business, while his brother Halim is a political leader who is keen to take his family and move to Pakistan as he believes Muslims will always be discriminated against in India and will have no future. In the process, the family is torn apart, as the ancestral house was in his name, and since he hasn’t transferred it to his brother, the property is taken by the government, leaving the remainder of the family in a mess.

Meanwhile, Salim’s business is failing as Muslims are viewed increasingly with suspicion, and his son Sikandar finds himself facing rejection after rejection at job interviews, with prospective employers telling him blatantly to try his luck in Pakistan instead.

Halim’s decision to leave also affects the family in another way — his son Kazim is engaged to Salim’s daughter Amina, but is forced to leave with his father. Kazim returns several months later, determined to marry the love of his life despite his father’s objections, but is arrested because he doesn’t have the right paperwork and has not reported himself at the local police station. A second engagement also breaks off when the boy’s family flees to Pakistan, leaving Amina so distraught that she commits suicide, leaving the family in a state of shock.

Also read: Dhool Ka Phool: Nehruvian secularism of Yash Chopra’s first movie is worth remembering today

The trauma of a family split down the middle is heartbreaking in its realism — haven’t so many of us grown up hearing stories in our own families of great-grandparents who just couldn’t get over the shock of being forced to leave their home, or who simply refused to do it? Why, asks Salim’s aged mother, should I leave the house I came to as a bride, the house I turned into a home, the home where my children have grown up? How will she face her maker, she demands to know.

There is no answer. And in that silence, Salim Mirza, who has stayed in India despite every temptation to move to Pakistan, because he believes that India is his home, makes a decision. But finally, exhausted from the effort, and broken from the loss of his daughter, he, too, decides to leave. It is only on their way to the station that the sight of a protest rally sparks something in Salim, rejuvenates him — and reminds him that if people fight the good fight together, that is worth staying for.

The production of the movie itself was an example of what solidarity can achieve. Written by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi (who was also Sathyu’s wife), the screenplay was adapted from an unpublished Ismat Chughtai story. Because of local protests, a false unit was sent to different locations, to throw locals off track. The film’s initial producers soon backed out, worried about the backlash given the controversial subject. So Sathyu, armed with very little, made this film with money given by the Film Finance Corporation (now the NFDC) and donations from friends. His friend loaned him an Arriflex camera, with which cinematographer Ishan Arya made his debut. The house that is portrayed as the Mirzas’ ancestral home in Agra was owned by a man who himself helped Sathyu find someone to play Salim’s mother — Badar Begum, whom they found in a local brothel.

The movie was held up by the CBFC for eight months, and it was only after repeated requests from Sathyu, who showed it to the government and media, that it was given a limited release.

In Bombay (now Mumbai), Bal Thackeray threatened to burn down Regal Cinema for premiering what he called a “pro-Muslim, anti-India” film. But he, too, was won over by Sathyu’s persistence and persuasiveness, and by the film itself. Garm Hava went on to win a slew of awards, including the National Award for the Best Film on National Integration.

Today, when the country is burning over the issue of who gets to be a citizen of India and who doesn’t, when people of all faiths are rising in protest to show solidarity with Muslims, one is reminded of this movie that was of its time and ahead of its time.

As a movie, no doubt, this was quite a stellar display of craft. However, to completely make this a problem of India was disingenuous. Just a bunch of communist trying to convince us that we were losers. Somehow, to place the blame completely at India’s door sounds like fraudulent narrative peddling.

One of the best International movies of all times. The acting was top class. So was the music. Maula Saleem Chisthi:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=RpW9a4ALBpI

Sad to see even after 50 years since this film came out, we’re nowhere near resolving the problem of partition.

What a movie! A moving tale. Brilliant acting by Balraj Sahani. It had moved me to tears, I remember, in 1974.