Watching Raj Kapoor’s 1951 classic Awara, I realised that how you think of that word depends entirely on your privilege. When I was in school in the ’80s and ’90s, ‘awara’ was used to describe kids who hung out with members of the opposite sex. It was what teachers called kids who bunked class to go to the canteen or, if they felt more daring, exit school to go watch a movie at the theatre. Awaragardi was something to aspire to because all the cool kids were doing it.

It was never, to our naive, privileged minds, about money or social status.

But Raj Kapoor’s movie was made in the 1950s, when India was struggling to emerge from the shadows of British rule, when the wounds of Partition were still wide open, when independent India was starting to develop its complicated relationship with money, wealth and education. In this context, the word ‘awara’ was not something indulgent parents and exasperated teachers said to errant students. It meant a vagabond, someone with no sense of home or, therefore, values, a tramp. It was used to tell you your place in the socioeconomic hierarchy — and it was never an aspiration.

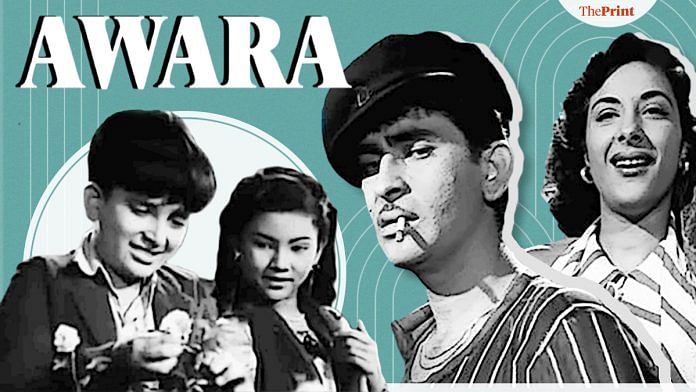

Watching this movie in the wake of the massive humanitarian crisis that has gripped India since the lockdown was imposed, one realises that Raj Kapoor was the original showman not only for the style and flair with which he made movies, but because that under that showmanship, he showed us what India really was.

Earlier, the words “Gharbaar nahin, sansaar nahin, mujhse kisi ko pyaar nahin” in the title song brought to mind the ironically cheerful Charlie Chaplin-esque persona that Raj Kapoor introduced in this movie, but watching it today, it feels almost as if he was foretelling what thousands of workers struggling to get home, many not making it, would feel, almost 70 years later.

In the week of Raj Kapoor’s death anniversary, it feels only right to revisit what is arguably his greatest movie, which feels all the more relevant today.

Also read: With Bobby, Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia set the bar for young love in Bollywood

Nature vs nurture with a Bollywood twist

Awara opens with Raj (played by Raj Kapoor) on trial for attempting to murder Judge Raghunath (Kapoor’s real-life father, Prithviraj Kapoor). The judge (played by Prithviraj’s real-life father, Dewan Basheshwarnath Kapoor), realising that Raj has not hired a lawyer, is about to get one appointed when a lawyer named Rita (Nargis Dutt) enters the courtroom, stating that she will defend Raj. She is not only Raj’s childhood friend and now lover, but has been in the care of Judge Raghunath ever since her father, the judge’s friend, died.

During the interrogation, Judge Raghunath repeatedly invokes one idea – that those who are born to criminals will become criminals, while those who are born to shareef log will end up on the right side of the law and the tracks. This concept of nature versus nurture is a running theme of the film, because, as Rita digs deeper into the interrogation, we find out that years ago, the judge, then up for magistrate-ship, had convicted a criminal’s son, Jagga (K.N. Singh), for rape without any evidence, using this very logic.

Jagga escaped and kidnapped Raghunath’s wife, Leela (Leela Chitnis), but upon finding out she was pregnant, let her go, because he realised that casting suspicions about the father of the child was his way of getting revenge. Raghunath, who had once bucked tradition to marry Leela, a widow, against his family’s wishes, then found himself unable to shake the thought that the child wasn’t his, threw Leela out of the house. That child was Raj.

On her own and living a hand-to-mouth existence, Leela manages to just about send Raj (played by a young Shashi Kapoor, the director’s younger brother) to a good school even as he polishes shoes on the roadside to help make ends meet, but he gets thrown out. He falls into the company of none other than Jagga, who grooms him and mentors him into a life of crime. Years later, Raj, now an adept criminal, tries to steal a woman’s bag. That woman, it turns out, is the one friend he had in school, Rita, whom he has never forgotten.

Rita and Raj fall in love, but her guardian, the judge, who has no idea that Raj is his own son, disapproves of him for being a worthless awara. Raj, meanwhile, keeps trying to quit his life of crime, but finds that it is difficult, for when employers find out about his past, they don’t give him a chance. This vicious circle of poverty and crime throws Raj into a spiral of despair and further crime, made worse by his insecurities about not being good enough for Rita.

Also read: Amar Prem tells the story of relationships that have no name but the power to break hearts

All for the love of a woman

In fact, even though the film is about Raj, it is Rita who is, in many ways, its soul. Her girlhood photograph, which Raj has kept all these years, is his reminder and his advisor to be good, it is what, at a crucial moment, stops him from committing a gruesome crime. She was his one ray of hope in his childhood, and she becomes that again when he needs it. But she is far from a manic pixie dream girl, whose sole purpose in the film is to support the leading man. She is a talented lawyer and a strong woman who stands up even to her imposing guardian, Judge Raghunath, who has taken care of her all these years.

Even her romance with Raj isn’t something flighty, although it has its moments of fun. It’s deep and passionate from the word go, and it’s not feel-good. Raj takes his insecurities out on her and it’s what makes their romance uncomfortable to watch but also beautifully portrayed in all its bruised, traumatic, brooding glory. This is what real human relationships are — messy, unpleasant, vital, painful. This, then, is the real message of the film – that everyone, whether a wealthy judge in his mansion or a tramp on the street, just needs a bit of love.

Also read: BR Chopra’s Naya Daur is still relevant for an India fighting age-old labour problems

i wish here was your email id too THE AUTHOR SAMIRA SOOD, it’s a beautiful, maudlin article.