In September 2021, a Pakistani bride, Ayesha Saif Khan, wore a pastel-hued, floral Sabyasachi lehenga choli for her nikah in London, bucking the traditional kurta with a gharara/sharara. It broke the internet.

Ayesha had married Junaid Safdar, the grandson of former Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. The fact that she wore an Indian designer to her wedding led to obvious criticism online — both from the general public and politicians.

There’s a certain insouciance to the Sharif women on fashion, though. Maryam Nawaz, Ayesha’s mother-in-law and a well-documented fashionista, wore a bespoke Abhinav Mishra creation at another of the wedding functions.

Pakistani brides are increasingly choosing Indian designers for their big day — even as the political relationship between India and Pakistan is strained and uncertain. There has been an almost complete ban on travel, trade, and any kind of cultural exchange between the two countries, especially since the 2019 Pulwama attack. But the cultural connection in terms of fashion in India and Pakistan goes long back. The difference in taste developed only after Partition.

It is evident that Pakistanis love Sabyasachi. But a cursory trawling through the social media pages of Pakistan’s most popular wedding photography and influencers’ accounts reveals a bigger phenomenon. Brides and fashionistas across the border are now opting for Indian designers and bridal couture like never before — Tarun Tahiliani, Anamika Khanna, Rimple and Harpreet, Abhinav Mishra, and Gaurav Gupta are all becoming hugely popular.

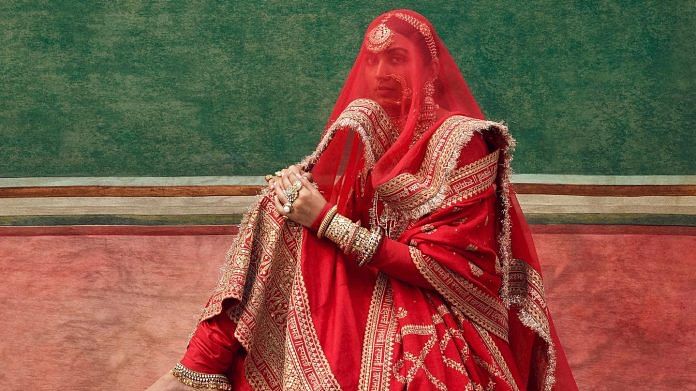

“When I saw a Sabyasachi lehenga, I saw the beauty of the cut that a lehenga should actually have. The work isn’t in your face; not loud or trying too hard. Sabyasachi just knows how to catch your eye,” says Lahore-based Dr Khadija Shafiq, 23, who got married last December in a pink lehenga by the designer.

Also read: ‘Guilt-free’ silk—this Meghalaya Eri silk village is tourist hotspot where weaving is sacred

What makes India’s designers tick

Indian designers are at a unique advantage due to the sheer variety of textiles and embroidery types available in the country. Pakistani couturier Kamiar Rokni explains that traditional high-quality embroidery work — zardozi, naqshi, dabka, gota, resham, sequins and so on — are native to and concentrated across North India and Pakistan. He points out how “the greater concentration of craftspersons” involved in such techniques is the reason Pakistani outfits are more detailed than Indian ones. “[And] since South India has a wider variety of weaves, Indian designers can focus on both fabric and embroidery work for their creations,” Rokni says.

The intermingling of fashion and cultural influences is fertile ground for creativity. A designer might source fabric from one place, get it dyed and embroidered from another, and might give the piece its finishing touches in an entirely different place. “The lehenga goes on an entire journey before it is ready for a customer,” says Varun Rana, designer-turned-fashion writer and freelance consultant.

Rana also notes that the wide appeal of Indian designers is because their designs appeal to a larger customer base — “the entire country”. He notes how some outfits have more embellishments and some less. Some will focus more on the fabric and some others on silhouette. “They don’t necessarily need to adapt themselves to a new market; something is bound to appeal to new customers,” he says.

Pakistani design consultant and veteran fashion journalist Mohsin Sayeed says that there is nothing new to this phenomenon, and the appeal is both-sided. “Back in the 1990s, well-heeled Indians would come to Karachi and [place] orders [for] Bunto Kazmi, Faiza Saqlain, and other such big names,” he says. He also mentioned that until a few years ago, big Indian designers were available in multi-designer stores in Pakistan, and Ogaan (also a multi-designer store) in India stocked top Pakistani designers.

Also read: A big fat Delhi farmhouse wedding went on a green diet. Lab-grown diamonds and…

Pakistan’s ‘national’ identity

There is an interesting historical context to Pakistani brides adopting the lehenga choli. In the ’70s and ’80s, no matter which socio-economic strata the bride came from, the wedding outfit across Pakistan was the same – a shirt (any form of fitted or loose kurta) with a gharara or sharara (any form of flared pant) and an embroidered dupatta. “[But] since the 2010s, lehenga cholis have begun emerging. This change in preferences among Pakistani brides is a more recent one and has also forced Pakistani designers to create lehenga cholis, which they never did before,” says Rokni.

Religion also plays a role when it comes to preferences, according to Rana and Rokni. “Brides here will rarely want to wear an outfit that flaunts their midriff in front of the qazi sahab on their nikah,” Rokni says.

It’s fair to wonder why Pakistani brides wearing different silhouettes should inspire this much discussion until one recalls how the salwar kameez was designated as Pakistan’s national dress to contrast with the ‘Indian’ sari. Even Pakistani men began to wear salwar kameez. Tanveer Jamshed, often hailed as Pakistan’s “pret wear revolutionary” and owner of the fashion brand TeeJays, sheds some light on this. “After the British left, the men wore suits, trousers, and shirts. The salwar kameez was the outfit of the mazdoors (the labourers). Then Zulfikar Ali Bhutto began wearing the salwar kameez to his rallies, to connect people through their clothes. That’s when Pakistani men began to wear it. He gave the outfit respect,” he says.

Mehr Husain, the co-author of Pakistan: A Fashionable History, says that apart from being a tool for self-expression, Pakistani fashion and its evolution are strong social and cultural indications of the country’s history. Saris, lehenga cholis were commonly worn in the country till salwar kameez became the norm.

“One of the things that distinguishes Pakistani fashion from Indian fashion is how we’ve merged craft and our basic silhouette, which combines both the East and West. The essential fashion culture in Pakistan has been “khulle kapde” (loose-fitting clothes) and darzi culture (getting it stitched from your local tailor),” Husain said in an interview with MIXTAPE Podcast.

The projection of a national identity through attire took a turn for the worse when Pakistan was under General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime. Pakistani nationalism became more vigorously Islamic. The sari was now seen as alien to Pakistan and Islam. Moreover, it took on a gendered aspect when women were asked to cover up and not “flaunt their bodies”.

“During General Zia’s time, women were asked to cover their heads, use bigger dupattas, wear burqas. In response, TeeJays introduced androgynous fashion but with signature design on the fabric, allowing women to retain some agency over their clothes,” Husain said in the interview. In 1986, singer Iqbal Bano performed Faiz’s revolutionary nazm Hum Dekhenge before a crowd of 50,000 people, making an emphatic statement clad in a black sari.

Sharia-compliant couture

How have things changed? Izzah Shaheen Malik, one of Lahore’s top bridal photographers and a recent bride herself, adds that today’s brides are more assertive about their attire — they are no more beholden to wear what their mothers or grandmothers wore before them. Now they have more options and don’t hesitate to choose from them. “I’m on the shorter side, so when I got married instead of wearing a farshi gharara that wouldn’t suit me as much, I chose a lehenga,” Malik says.

Despite the change in choice and outlook, enforced modesty is evident in the designs – longer blouses that don’t bare much midriff, sleeveless blouses are rarely seen. It’s what a Pakistani writer and cultural commentator, speaking on condition of anonymity, describes as “sharia-compliant Sabyasachi”.

“It’s not culturally common to bare the midriff in Pakistan, so there’s bound to be some awkwardness initially,” says culture and fashion writer Saba Imtiaz who authored a deeply researched article about the attitudes of Pakistanis toward the sari. Over the last few years, there have been changes in certain ethnic communities that used to have segregated wedding receptions. “In Delhiwala weddings in Karachi, there is now a third “mixed” enclosure with the friends (of both genders) of the bride and groom [mingle],” says Imtiaz.

Even the guests’ outfits have changed now — younger women are wearing more saris. “I assume this, along with social media, makes it easier for the brides here to opt for a choli.”

The power of social media

The influence of Bollywood is impossible to escape in the Indian subcontinent, especially when it comes to weddings. Speaking about her childhood during the ’90s in Lahore’s Ichhra Bazar, Imtiaz recalls how the shops under her house were chock-full of Madhuri Dixit’s outfits shown in Hum Aapke Hain Koun (1994). Later on, Aishwarya Rai’s outfits from Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999) and Devdas (2002) served as inspirations. What were the fashion influences earlier? “It was what we saw in magazines and on the big screen — it’s not like now where you can see every inch of the fabric that everyone has worn to every wedding they attend on Instagram,” says Imtiaz.

Every bride these authors spoke to mentioned how Bollywood’s influence on Pakistan is more than just about lehengas. Pakistanis are adopting “sundowner” mehendi and haldi ceremonies, playing Bollywood wedding songs, and emulating movie stars or famous scenes from movies as well. “Bollywood has already been huge for years [in Pakistan]. But Indian fashion for Pakistanis has only recently come to the rise,” says Tahrim Munir, 23, who lives in Dubai.

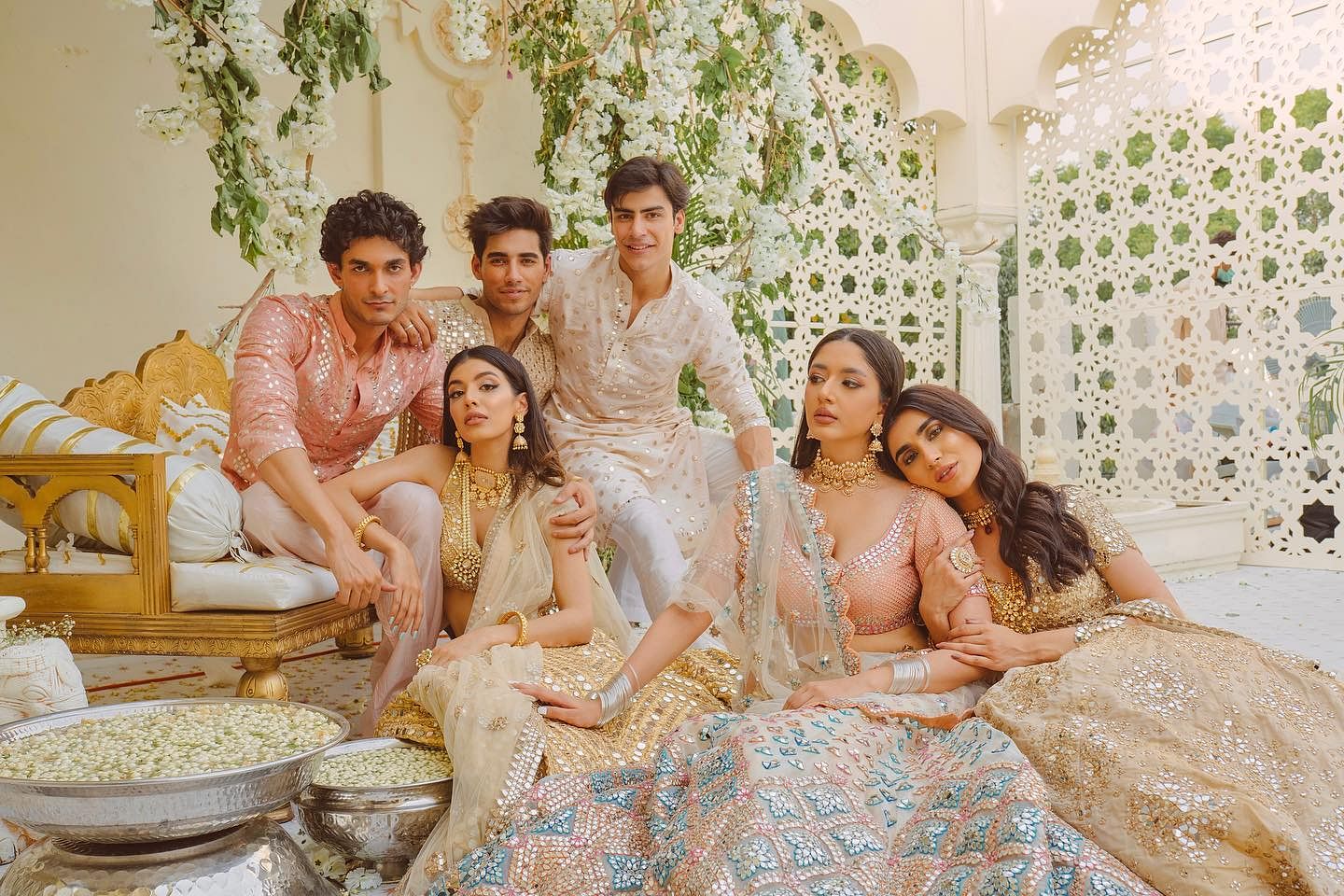

Munir opted for an Abhinav Mishra outfit for her big day after her sister-in-law Vaneeza’s white-and-gold wedding lehenga by the same designer went viral on social media. “Leading photographers, especially accounts like Sara Idrees and Pictroizzah, post pictures of brides and weddings. Thousands of followers see the uniqueness in the dresses, the weddings, events. So they influence choices and trends,” she says.

It appears that the recent popularity of lehengas owes more to the all-pervasive power of social media where wedding photography ends up glamourising designers even more. Izzah emphatically states that social media marketing is as essential to a designer’s popularity as their designs, if not more. “Sabyasachi is the king of marketing, and therefore the most popular. His [social media] campaigns, with the brides in distinctive designs, shot against various exotic outdoor locales set the bar.” She continues, “Abhinav Mishra is the most popular [designer] here after Sabyasachi because of his campaigns.”

Amid such political tensions, the industry has much to gain from the power of social media. In an interview with American magazine Architectural Digest, Sabyasachi said that he stopped believing in ramp shows because 65 per cent of his business reportedly originates from Instagram.

In 2021, Izzah and Abhinav Mishra collaborated on a marketing campaign shot in Lahore. Pakistani models wearing Abhinav Mishra’s signature glitzy, mirror-work lehengas and kurtas were seen posing casually against a stunning backdrop and dancing to hit Bollywood songs. The campaign quickly went viral, opening a market for a relatively unknown Mishra. Izzah shares that she hasn’t stopped shooting Abhinav Mishra brides since the campaign came out. On his part, Abhinav Mishra says, “Social media breaks barriers between our two worlds.”

When it comes to wearing Indian designers, there is also the lure of wearing big brands. “Brides in Pakistan don’t mind wearing a completely different aesthetic and silhouette that’s not traditional for them as long as it is a Sabyasachi or an Abhinav Mishra,” says Shallah who runs Dream Closet, a bridal styling service in Europe and Pakistan. Indian designer Gaurav Gupta, famous for his sculptural couture, is rapidly gaining popularity among Pakistani brides. He notes that “high-net-worth individuals” in Pakistan wearing his outfits has increased his brand’s reach. Dr. Nyla Shafiq, Khadija’s mother, adds that today’s brides are more brand and design-conscious.

Sabyasachi, the ‘affordable’ luxury option

It’s not just the uber-rich in Pakistan who are wearing Indian designers.

Rokni explains that the market for designer bridal wear in Pakistan falls into two categories. One, the extremely wealthy for whom wearing designer outfits is not a big deal. Second, the “relatively less elite” clientele for whom weddings are their first experience of luxury attire. “For these women, it is cheaper to get an off-the-rack or lower-end Sabyasachi or Abhinav Mishra with added costs than a high-end Pakistani designer,” says Shallah.

An original, though lower-range and off-the-rack, Sabyasachi lehenga is cheaper than one by a top Pakistani designer. This is when one takes into account international shipping costs – including routing it through a third country (most often Dubai) and customs. A Sabyasachi lehenga costs PKR 6 to 12 lakh, whereas both mid-range and high-end Pakistani designer outfits start from PKR 25 lakh. It’s an irresistible option for brides.

With acute difficulties in trade and customs between the two countries, Dubai has become a go-to middle ground. Tahrim Munir, for instance, opted for her mehendi photoshoot with a bespoke mirror-work Abhinav Mishra lehenga in the sands of Dubai’s desert.

Mohsin Sayeed also points out how Indian clients too opted to buy Pakistani couture via Dubai and vice-versa. Not surprisingly, two of the biggest names in both countries – Sabyasachi and Faraz Manan – have opened shops in Dubai.

“Sabyasachi has created a giant affordable luxury bridal market here,” says Rokni. Abhinav Mishra is also catering to it.

Mohsin Sayeed points out that the lack of ready-to-wear bridal outfits among Pakistan’s top designers is another reason why brides are choosing Indian designers. He emphasises how Pakistani couturier Bunto Kazmi is “booked until the end of 2024” and “not even taking appointments”. Umar Sayeed, a big name in Pakistani bridal wear, is also booked for the 2023 wedding season. Bunto, Umar, and Haroon work on a customised basis and don’t have ready-to-wear collections. “Sometimes, [it] takes six to eight months to make a piece,” says Mohsin. For anyone planning a wedding within that period of time, Indian designers are the preferable option.

The size of the wedding attire market in India is mind-boggling. According to a KPMG report, India’s wedding market was worth nearly $50 billion in 2018. Indian designer Karan Torani explains that the presence of a greater number of global brands in the country has made designers more competitive — be it in pricing or presentation. This combination of factors also makes Indian designers appeal to a larger market.

The massive size of this market owes substantially, if not entirely, to South Asia’s obsession with lavish weddings. Commentators such as Sana Tahir Butt, a fashion writer from Lahore, attribute the rise in wedding expenditure to Pakistan’s ‘wedding industrial complex’. “There is a very strong, capitalistic need to not just consume and over consume when it comes to weddings but also this need to one-up each other,” Butt notes. She emphasises how this was “very prominent” among the Pakistani elite. The culture of one-upmanship, she notes, is also exacerbated by social media.

It’s no secret that weddings among the Indian and Pakistani elite have budgets running up to several crores. “Of course, Sabyasachi lehengas would be so popular in a country that hasn’t seen land reforms!” says an Indian editor and writer who did not wish to be named.

Politicians have even tried to discourage excessive spending on weddings, with the government of the Punjab province in Pakistan enforcing a ‘one-dish policy’. In 2022, Congress MP Jasbir Singh Gill also called for a similar law in India.

Imtiaz elaborates on the shifting nature of status symbols in Pakistan, and how getting talent or designs from across the border is a part of the signalling. “In the 2000s, it was getting Sukhbir to perform at weddings in Lahore, now it’s getting a Sabyasachi lehenga,” he says. If it can’t be a musical performance, it will be the venue. If it’s not the venue, it’ll be the outfit and jewellery.

Such kind of cultural signalling was prevalent in India too, says Imtiaz. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan performed at Rishi Kapoor and Neetu Singh’s wedding in 1980 when Raj Kapoor invited him.

What lies ahead?

Logistically, Indian designers have another advantage — they are more used to dealing with international clients. Both Butt and Izzah attribute the steep increase in popularity of Indian designers in Pakistan to the pandemic: Indian designers are better equipped to deal with clients online.

“Indian designers and their associates are used to doing all their consultations online. From discussing prices to deciding designs and taking measurements, all of it happens over video calls,” says Butt. The pandemic made people explore more online options, and there was no going back.

Gaurav Gupta says that the only obstacle he has faced till now is the problem of direct sales and shipping. “We get a lot of queries through social media; my team is connected with clients through online channels as well,” he adds.

Whether this influx of Indian designers in Pakistan will mark a reciprocal shift – a greater demand for Pakistani couture in Indian – remains to be seen. Equally uncertain is the faint hope for Indian and Pakistani designers to put political tensions and rigid trade ties aside, set up shop across the border, bring fashion shows to each others’ ramps, and collaborate on more projects.

Karan Torani concedes as much, saying that hate and political differences are affecting the business and creating multiple hurdles. “It’s unfair to my client who might be living in Islamabad but wants to physically see all my pieces and try them on. They’re expensive items and [customers] shouldn’t have to make a compromise,” he says.

But designers haven’t given up. “We’re still working toward something to ensure that we find a way to give back. We’ve only gotten love from people across the border, it’s never been harsh,” says Torani.

Cross-border cultural exchange — art, music, fashion, or literature — can’t be stopped. And that’s what politicians don’t understand, says Sayeed.

Mythili is a lawyer and writer. Sabah is an independent journalist who reports on human rights, law and culture.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)