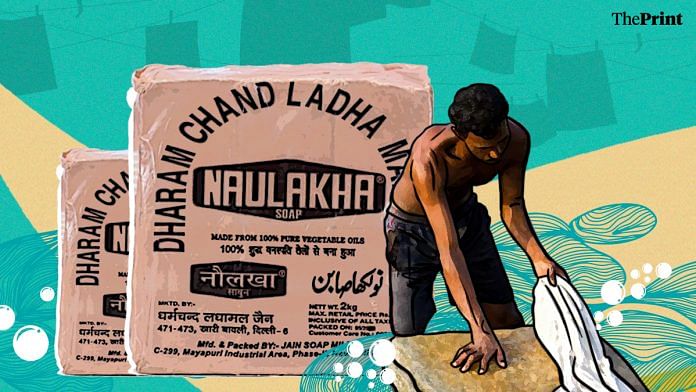

On the eve of Indian Independence, there were few FMCG goods produced in the domestic market. And among those that were, few had a consistent and standardised quality. But Naulakha Sabun – a clothes-washing soap that started production in 1895 and enjoyed a dedicated following from the very beginning.

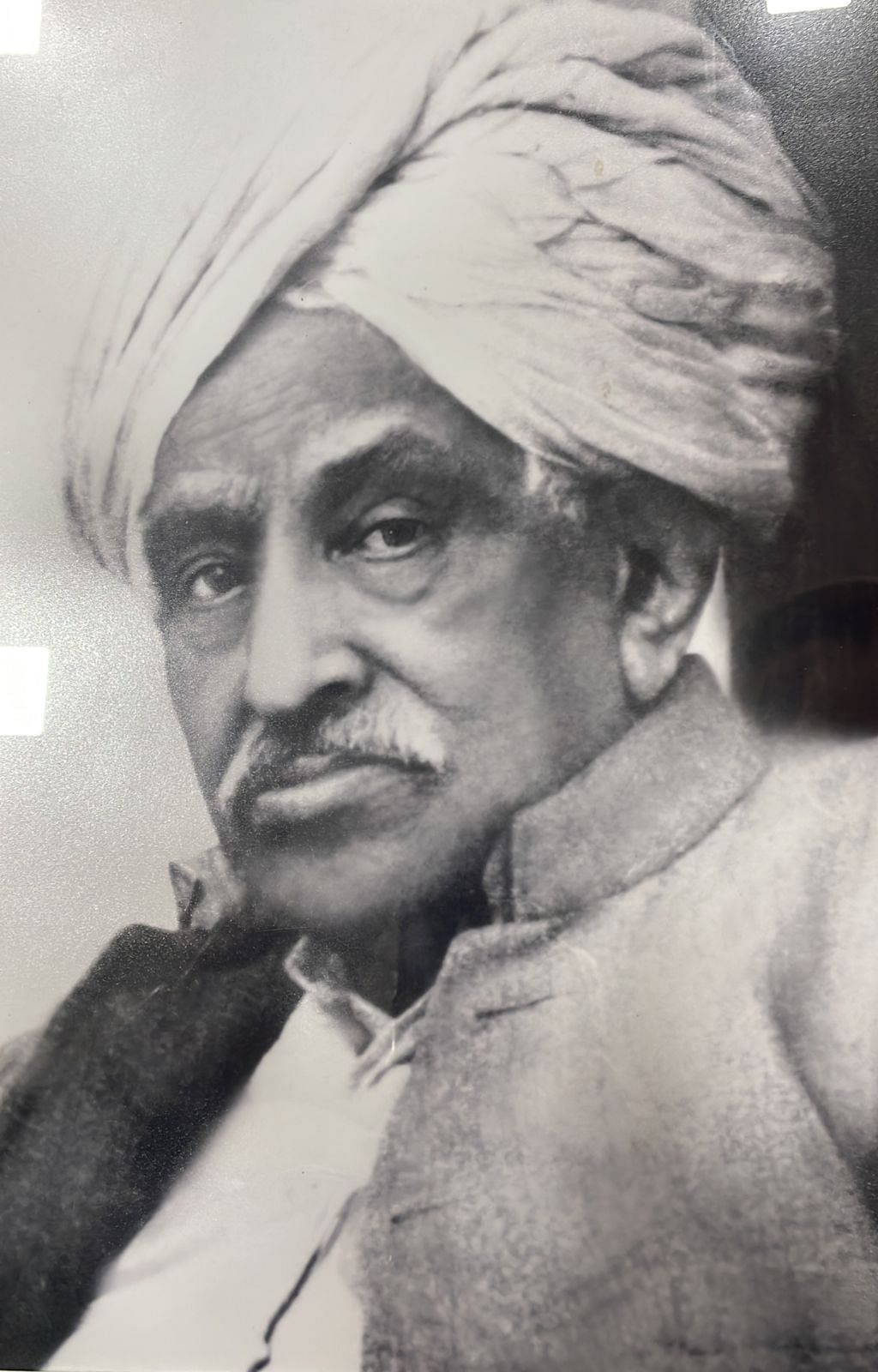

The story of this establishment began when Ladha Mal Jain was barely 14 years old – but fired up about the idea of starting his own business. Chatting with friends and discussing ideas on what to dip his hands into, someone suggested to him that washing soap is a great idea because it’s a non-perishable item used in every home on a daily basis. This stoked the young boy’s imagination. He bought a big kadhai (cauldron) along with the required ingredients and began the process of experimentation. After many rounds of trial and error, he was finally able to make a solid piece of soap that was not only effective in cleaning clothes but was soft on the hands too. Though not a branded product then – the brick-sized pale yellow soap quickly became popular in Lahore and adjoining areas. Soon, traders and stockists began to sell it in other cities across north India.

“Hamein hamesha se sirf ek kaam aata hai – sabun banao aur bhej do. (We just know one thing – make the soap and send it off). In all these years of operation, we have never spent a single penny on radio, TV or newspaper advertising. We sell by ‘word of mouth’ because even today we make this soap for the woman who washes clothes with her hands. Our soap will not cut or bruise her hands because we test each batch by keeping a small crystal on our tongue. Tongue is the best test. That is the kind of concern we have for our customers. There is no adulteration in our materials. Many soap makers have tried to copy and create duplicates but we never chase duplications by going to police stations or courts. Best IPR is customer feedback,” said Ravinder Jain, the third generation owner of this centurion brand.

Ladha Mal had seen prompt success when his soap developed a loyal customer base. He soon set up a small ‘Karkhana’ as the small cottage industry was known at that time. Surprisingly, there were no other competitors in the same quality or price range so the cauldrons kept multiplying and the factory became bigger and bigger. Ladha Mal got married and had three sons and three daughters. He got married again and had another three sons and three daughters from his second wife. The entire clan lived together in Lahore.

After the Partition in 1947, the Ladha Mal Jain clan had to abandon their home and manufacturing units overnight and flee to India. Empty-handed and with no funds, the family landed in old Delhi after a short interlude in Ambala. Just when the family was on the edge of doom, a miracle happened. One Delhi-based soap trader who had purchased a big consignment from Ladha Mal reached out to him with the pending dues. Like an ant climbing on a frail straw in swirling waters, the family managed to start again from scratch. Ladha Mal rented a two-storey house on Sadar Thana road. The family lived upstairs and the ground floor was prepared to set up the ‘batti’ – as the fired up cauldrons are called in soap industry lingo. It was an entirely family-owned and family-run operation with the father and six sons working together.

Also read: India’s first ‘big’ bathing soap failed because it was OK

A new beginning

In this new innings in 1947, Ladha Mal decided to wrap the soap brick in a pale pink butter paper and named it Naulakha Sabun. No one in the family knows for sure what inspired Ladha Mal to pick that name.

“It could be based on a pavilion in Lahore Fort or on a village in Pakistan – which was our family base before Partition. Whatever may be the real reason, the name of the soap is a big reason for its success,” Ravinder Jain said. He explains how Naulakha (meaning nine lakh in Hindi) is considered sacred in Hinduism because it’s the number of Brahma, the creator. “This number is a symbol of wisdom, fulfillment and completion. Perhaps it gave a feel good factor to women homemakers who have always been our main clients.”

The makers of Naulakha Sabun claim they have remained unchanged. All six brothers and their extended families still work together and no one has chosen to branch out so there are no external collaborations and no competition (not even from the modern-day washing machines). They only produce as much soap as their own liquidity permits them.

“Na udhar mein dete – na koi loan lete. Banaya, becha aur bas nakki (We give no credit, we take no loan. We just make our soap and sell it). We have the lowest possible costs because we have no superficial expenses. We make small profits but that is also our strength. That’s why no one can beat us,” Jain added with a wry smile.

This article is a part of a series called BusinessHistories exploring iconic businesses in India that have endured tough times and changing markets. Read all articles here.