Move over wine and cheese, and Napa valley tours: Maharashtra’s vineyard tourism has a new hit combo. It’s ‘bhakri’ and wine.

Fresh bhakris—flatbread typically made from jowar (white millet), bajra (pearl millet) or rice flour—are flipped over a cooking stove. On another side, ‘pithla’, a quintessential Maharashtrian dish made from gram flour, is simmering in a pot.

Manoj Jagtap, who goes by the moniker ‘wine friend,’ specialises in wine tourism. He makes his patrons sit down with their plates in front of them in a neat line—the traditional Maharashtrian ‘pangat’—and savour the local fare, each course paired carefully with a glass of wine from one of Nashik’s local vineyards.

India has neither the unending lush vineyards of Napa Valley, Tuscany or Bordeaux, nor a culture where wine has been a staple for centuries. But, over the last two decades, North Maharashtra’s Nashik has seen the growth of a robust wine industry that can offer at least a fraction of their charm and experience.

“We first start by telling most of our visitors that medically, more than 100-110 ml of wine per day is not recommended,” an employee at the Grover Zampa vineyard in Nashik said.

As per data from the Maharashtra tourism department, Nashik has 29 operating wineries, most spread across areas such as Dindori, Niphad, and Igatpuri. The beverage is gradually gaining acceptance in the local culture and shedding its tag in India as an elitist drink.

“Earlier, the misnomer was that wine is only a rich people’s drink to be had in five-star hotels. Over a period of time, the aura around wine has diminished, and this is what we want. We’d rather [prefer] that most people drink wine the right way. If this kind of education happens, it will really help the industry,” said Monit Dhavale, senior vice-president in charge of hospitality at Sula Vineyards.

The size of the Indian wine market touched Rs 1,900 crore in 2020, as per the market information report cited by Sula in its Draft Red Herring Prospectus with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) for its Initial Public Offering (IPO). Last month, Sula became the first Indian winemaker to launch an IPO. It was listed at a mild premium before dipping.

Also read:

The Indian wine county experience

Anecdotally, many industry players peg Nashik’s contribution to the wine market share at 80 per cent. This is mainly due to the region’s climate—warm days and cold nights—and the free-draining soil, perfect for producing winemaking grapes of different varieties.

“All the wineries are in a 50-kilometre radius, and each has something unique to offer,” said Jagtap, who draws up personalised itineraries for vineyard visits, wine tastings and food pairing sessions, keeping in mind his clients’ interests and time constraints.

Sula is a huge success story, which makes wines that appeal to India’s sweet palate. As per company employees, the highest-selling wine in Sula’s tasting room is the Late Harvest Chenin Blanc, a dessert wine with strong notes of tropical fruit and honeycomb.

Chandon is an exclusive luxury experience, but there are also some boutique and family-owned wineries where makers personally guide tourists through the tasting experience.

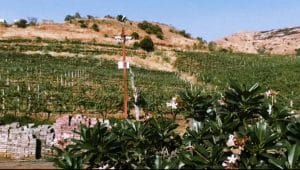

A 46-kilometre drive from Nashik to Igatpuri—first through a smooth highway, then a crowded village marketplace and later desolate winding roads—brings us to the ivy-covered bare shell facility of Grover Zampa, located at the foot of a 35-acre hillock. About 15 acres of it is draped in vines bearing grapes of the Tempranillo, Viognier, Grenache and Chiraz varieties.

The premises are undergoing an overhaul, an employee who is in charge of the company’s Nashik winery said. A brand new tasting room, lined with oak barrels on both sides, wine coolers in a corner, a long table at the centre, and a glass-covered premium section replete with spouts and basins, is 90 per cent ready.

“The spouts and basins [have been included] because the right way to taste different wines is to spit them out, not drink them,” said the winery in charge, who did not wish to be named.

There are plans for a luxury hilltop resort for which Grover Zampa is looking to tie up with a five-star hospitality company. It plans to open beautiful outdoor and indoor restaurants adjacent to each other, and a small artificial fish pond, waterfall and wine library.

Before renovation, Grover Zampa used to get at least 50-60 visitors per day—the number even touching 120 on weekends.

If and when the vines bear grapes, visitors are taken up on the hill, their journey interspersed with exciting trivia. These info bytes include questions like how the basalt rock in Nashik helps grapes retain more minerality, how Nashik’s high-fertility volcanic soil adds a hint of smokiness to red grapes, and how all barrels bear the farmer’s last name to ensure consistency.

About 20 minutes from Grover Zampa is Vallonne Vineyard, a picturesque drive with water bodies on either side. The unique selling point of this small, boutique vineyard is the view: It is a lakefront location with a 10.5-acre vineyard.

Vallonne likes its exclusivity. It has only four resort rooms and makes only about 70,000 to 80,000 bottles a year, about 40 per cent of which is sold at the winery itself. Moreover, it has three daily wine-tasting batches, all personally guided by chief winemaker Sanket Gawand.

“The clientele that comes to us are those who already understand wine—those who have travelled internationally and tasted different wines. More commercial winemakers usually make wine for the masses that is on the sweeter side, whereas our wines are dry,” Gawand said. Vallonne’s most premium wine, Anokhee Grand Reserve, priced at over Rs 3,000, is said to be so exclusive that it is only made when the climatic conditions are ideal. “In the last 13 years, we have made it only five times,” Gawand said.

Besides, Vallonne also takes personalised orders for special occasions. The wine is aged in a 28-litre barrel that yields 38 bottles. “You can select your grape, [and] the ageing duration. You can also personalise the label on the bottle with a photograph or a name. We get a lot of such orders for major occasions such as a milestone birthday, a wedding or an anniversary,” Gawand added.

Closer to Nashik, the wineries of Sula, Soma and York are all lined up on a road colloquially known as ‘wine street.’ An entire hospitality zone has come up around the three wineries, with hotels, resorts and Le Fromage, an artisanal cheese-making company set up in 2016.

Further north in Niphad is a small family-grown business called Nipha Wines, owned and managed by husband and wife Ashok and Jyotsna Survade. “The experience there is completely different. When we take tourists there, they often see Jyotsna Survade working the tractor in the vineyards or spraying on them. Their teenage daughter runs a cafe on the premises and offers coffee tastings,” said 52-year-old ‘wine friend’ Jagtap.

Also read: World’s first ‘Chai-infused gin’ from Edinburgh has Assam connection

A cultural shift in the works

It is a lazy Wednesday afternoon, and the winter has set in just enough to blunt the harshness of the sun. A young mother poses with her infant on a bright yellow bicycle created as a photo spot with Sula’s logo in the background. A few feet away on a deck overlooking vineyards, a couple converses deeply over a bottle of Rosè. A few tables away, a large family spanning three generations munches on pakoras as a white wine chills in an ice bucket next to them.

On the other side of the property, 22-year-old Supriya Atewar is strolling with her father and her Golden Retriever, Rover. “I had come for a tour of the vineyard when I was in college. My parents and I were on our way back home to Panvel [near Mumbai] from a visit to Hatgad [a fort town north of Nashik], and I thought they might really enjoy seeing a vineyard.”

Sula Vineyards’ Dhavale said wine has got social acceptance over time. More women are taking to wine, and drinking it as a family-time activity is not uncommon any more. He added that, on average, about 30 per cent of Sula’s visitors opt for a wine-tasting package.

The Nashik district has traditionally been a pilgrimage destination and an industrial hub. But, Dhavale said this rarely clashes with its emerging identity as a wine country. If anything, this image only feeds Nashik’s booming wine empire.

“There are many tourists who come to Nashik, visit a pilgrimage site on one day and a vineyard the next,” said Dhavale. Similarly, many foreign company executives visiting Nashik’s industrial areas also end up seeing the wineries.

“When people come to us and do tastings, we try to explain the basics of wine to them. The best way to spread awareness about wine is education, and that can only happen at wineries,” said Gawand.

This visible shift, however, is primarily urban. Representatives from multiple wineries said their visitors mainly come from Mumbai, Pune, Bangalore, Goa and Ahmedabad. From among Tier 2 cities, only patrons from Nashik partake in wine tourism.

“The global wine tourist destinations have been built on decades of wine being a part of their cultural, economic and social life. We will reach there someday, but it will take at least two more generations,” said Jagtap.

Since 2009, Jagtap, who is also a coordinator at the All India Wine Producers Association, has organised vineyard tours for over 3,500 international and double the number of domestic tourists. He has tasted wine from almost every vineyard in Nashik but faces drinking restrictions in his own house.

“The unfortunate truth is that I teach the whole world about wine, but I have been unable to teach my wife about it,” he said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)