A host of video- and live-streaming-based apps have spawned a universe of celebrities whose fans are helping them earn some serious cash.

New Delhi: A bespectacled middle-aged woman is lying back, the camera focused in a close-up of her face, video-chatting with two men about a power cut, among other things. Before cutting the live-stream, she tells one of them that she had “followed” him on the app, and he should return the favour.

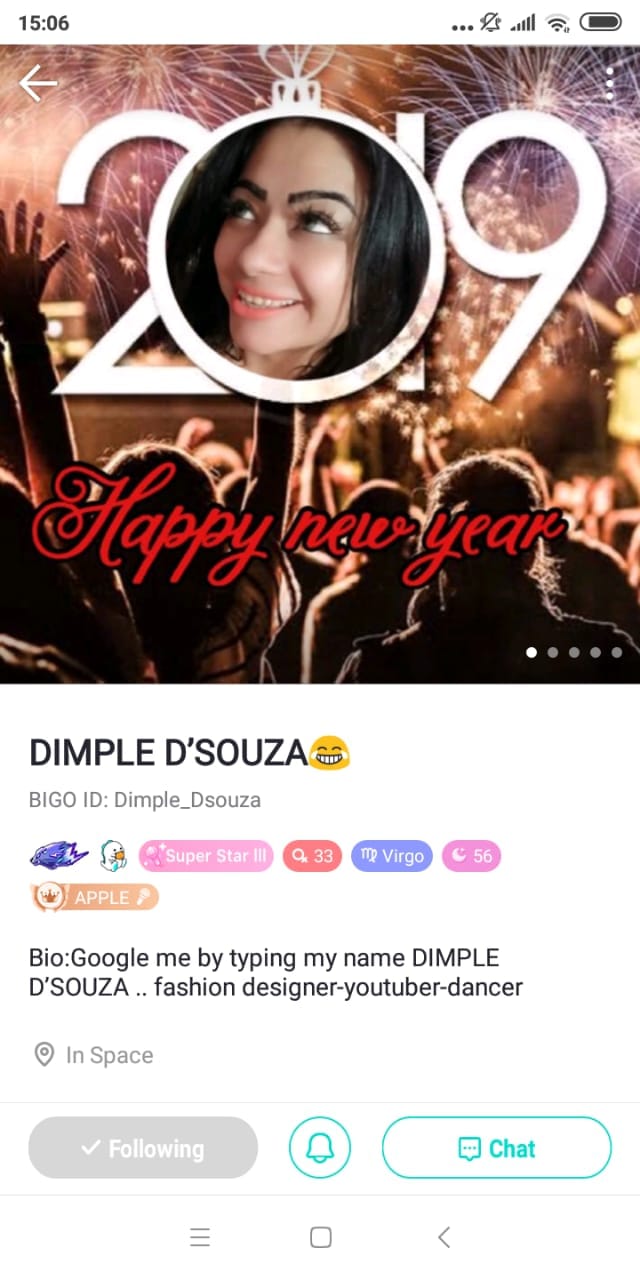

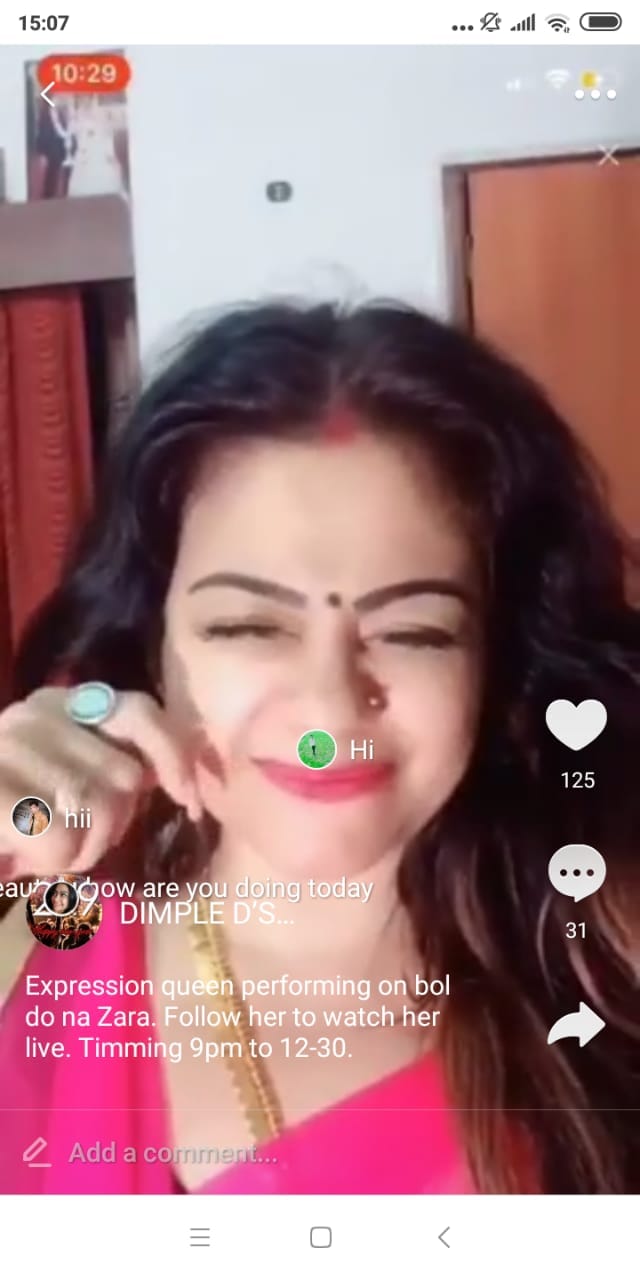

As a song plays in the background, Dimple D’Souza, a light-eyed 33-year-old from Chennai, dances in front of the camera, though users can only see her arms and face. Her face is a sea of expressions, and her 3 million followers can’t have enough, their excitement evident in the flood of comments on the screen. In one of her live-streams, wearing a full face of make-up, she urges her followers, “Come on, give me some stars. Just one more”.

Welcome to Bigo Live, one of the recent social media innovations where live-streams of perfectly mundane conversations and activities are helping people become stars of their own universes, and earn lakhs from devoted fans.

There are no DIY tutorials or cooking lessons like their more popular counterparts YouTube and Instagram. Users on these apps can sit in front of screens eating, making fun of their followers, and participating in small talk with strangers, and that’s it.

For instance, Dimple, a fashion designer, rarely churns out content about fashion. Instead, she talks about her day in a mix of Hindi and English, plays games with other Bigo Live hosts, and asks strangers and viewers to follow her and send her ‘gifts’, virtual objects like Christmas trees she can later encash through a digital wallet service.

Doing this, Dimple told ThePrint, earns her a tidy Rs 5 lakh a month.

“I would never make so much at a 9 to 5 government job…” she added. “I definitely make more money from Bigo than from my other job.”

Another user, Kumar Sourabh, a 19-year-old student from Delhi, was looking for an app to improve his “interpersonal skills” when he found Bigo Live, a Singapore-based, largely-Chinese-owned app.

Conducting live-streams with the energy and flair of a radio jockey, Sourabh said he made up to Rs 97,000 a month by spending as few as 80 hours on the app.

Spotting a treasure trove

Developers identified video and live-streaming apps as a treasure trove when the Chinese app ‘Musical.ly’ became a global pop culture hit, including in India, during 2016 and 2017. Launched in India in August 2017, Musical.ly had 15 million users by February the next year.

On Musical.ly, users could record and share 15-second video clips of them dancing or lip-syncing, with a host of special effects on offer.

Musical.ly has since been merged with another video-based app called TikTok, which is owned by Chinese tech behemoth ByteDance, now the world’s most valuable startup with a net worth of $75 billion.

Users’ passion for the medium continues to ride high, with apps like Bigo Live, TikTok and MeMe Live, a Taiwanese offering, especially striking a chord beyond India’s Tier 1 cities.

Bigo Live, for example, claimed in January 2018 that it had notched 50 million Indian users in eight months, TikTok was named one of India’s most entertaining apps in 2018 by Google Play Store, and MeMe Live, which largely targets east Asia, is nevertheless gathering Indian users with competitions that offer lakhs in prizes.

With many of these apps virtually unheard of among India’s English-speaking urbanites, these legions of fans and followers mostly come from small towns, and prefer vernacular content.

“We believe that creativity is not just limited to the audience belonging to Tier 1 towns who speak English,” said a TikTok spokesperson. The app is seeing “growth across Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Marathi, Punjabi and Kannada speaking communities, to name a few”.

Also read: Apps, drones, online markets as Coffee Board looks to improve crop productivity

Like playing a game

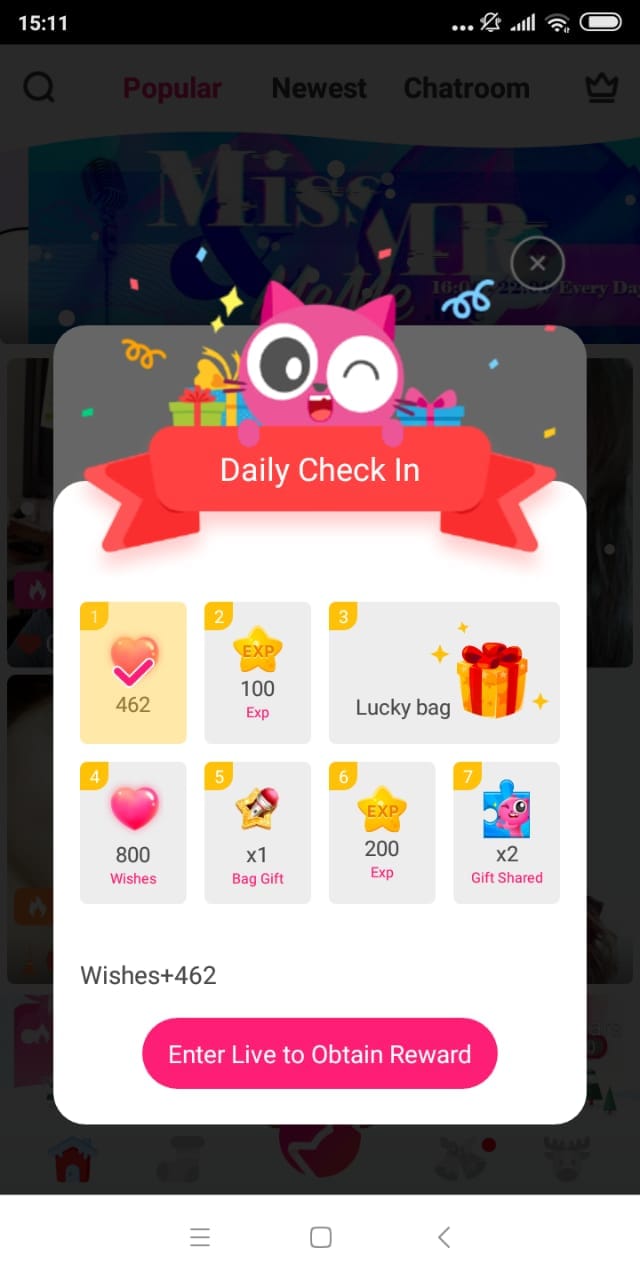

There are different ways users earn money on different apps, with ‘gamification’ emerging as a popular method.

To ‘gamify’, an app turns everything a user can do on the platform into a game.

Bigo Live, for example, has multiple virtual tokens like “beans” and “coins”, which are earned for using the app to consume and make content.

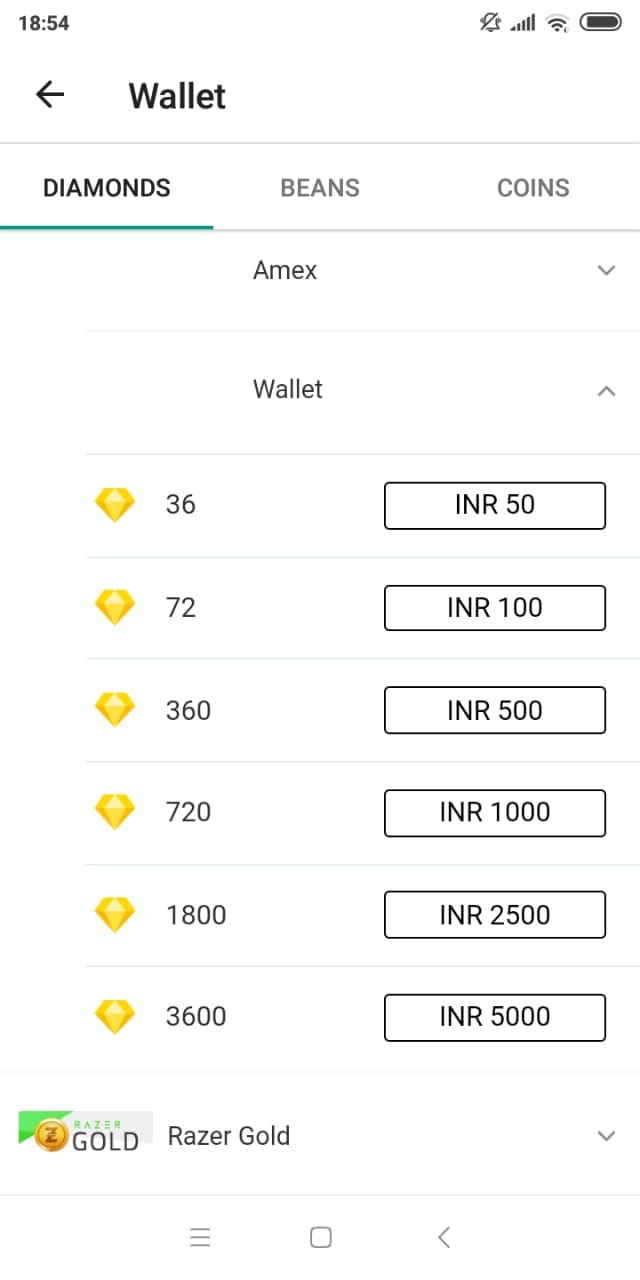

Bigo Live’s primary currency is called ‘diamonds’, which followers can purchase via methods like debit or credit card or Paytm to lavish their chosen content producers with gifts. At present, 36 diamonds cost Rs 50.

Followers can use the diamonds to buy virtual gifts, like a ‘Christmas tree’ worth one diamond, or a ‘family shield’ worth 999 diamonds, for content creators. When a viewer directly sends a diamond to a broadcaster, it is reflected in the latter’s account as a bean.

Collecting these virtual tokens is important for Bigo Live hosts, who have to fulfil certain stringent conditions to earn serious cash, like broadcasting for at least 40 hours a month, and gathering a set target of beans/diamonds.

It’s a win-win situation for user and app, Akash Senapaty, a former executive with game developer Zynga wrote in a blog post last year. Bigo Live, he said, pockets $54 as commission for every $100 earned by a user, with the latter getting $16. The remaining $30 goes to the platform hosting the app, for example, Google Play Store and iTunes.

MeMe Live employs gamification for revenue too: According to the Google Play Store, in-app purchases cost between Rs 10 and Rs 19,900. So does TikTok, from users purchasing “coins” to buy “gifts” that can then be given to content producers: The gifts reflect in the latter’s account as “diamonds”, which can then be encashed.

The popularity of these apps is bringing in sponsors too. According to Heer Naik, 19, one of the most followed Indian TikTok users with 3.1 million ‘fans’, brands like Myntra, Himalaya and Nickelodeon pay her as much as Rs 30,000 to 35,000 for every 15-second video she makes to endorse them.

Other sources of money include contests: For example, VivaVideo, a Chinese video editing and streaming app, holds competitions where publishers can get Rs 500 if they get the most number of likes.

TikTok’s #1MillionAudition competition encouraged users to make a video and reach 1 million likes and gain 1 million followers for a chance to win an Honor 10 smartphone and $500 in cash.

“These apps have essentially cracked the code on monetising by doing two things: Targeting a consumer base outside Tier 1, which is not saturated by similar apps like YouTube, Instagram, and by adopting user-acquisition strategies of successful gaming apps,” said tech policy consultant Mandar Kagade. “In addition, these apps have the added benefit of offering a platform to become famous.”

Almost famous

Meanwhile, apart from the money, users of these apps are finding the fame they have always craved.

“My real dream is to be famous — as a radio jockey, a news anchor, whatever,” said Shivangi Agrawal, a 22-year-old Bigo user from Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. “Bigo gives me a platform and a global audience to live my dream.”

She has been in Mumbai for two months, trying to be discovered as the next big star while working at an IT company. “I don’t want to be just a normal employee all my life,” she told ThePrint.

Shivangi takes her broadcasts on Bigo so seriously, it’s on her LinkedIn profile: “Shivangi Agrawal — Official host at BIGO LIVE/News anchor”.

US-based Naik, 19, originally from Surat, Gujarat, said she was now recognised by people on the streets when she visits.

“I was recently in India and people recognised me on the streets. It felt so good,” she added.

Also read: 10 apps on India’s smartphones you’ve probably never heard of

No walk in the park

However, contrary to expectations, this world is not immune to the challenges of run-of-the-mill jobs, like the gender pay gap.

Simply because female broadcasters tend to receive more views and attention from users, at one point, Bigo required its female hosts to collect 20,000 virtual tokens to earn the same amount a male would get from 8,000 tokens.

Some users also complain about “tough work conditions”.

A male BigoLive user with 4.2 million followers said he stopped using the app because he had to increasingly spend too much time to earn the same amount of money.

“At first I had to achieve only 8,000 diamonds to earn $200-240 a month,” he added. “But this was changed [by BigoLive] to 50,000 diamonds, which was much harder to achieve.”

Some other users expressed a similar sentiment, saying they had abandoned Bigo Live because meeting the targets was too difficult and time-consuming.

Dimple told ThePrint that she sometimes had to spend as long as nine hours a day on the app to maintain her Rs 5 lakh/month income.

An email questionnaire sent to Bigo Live and MeMe Live on the complaints had not elicited a response by the time of publishing. The report will be updated when they respond.

Predictably, in a universe where user engagement is directly proportional to one’s income, adult content is frequently peddled to gain traction. Generally, this means cleavage shots, with some seductive biting of the lips.

Sexually provocative thumbnails and softcore pornography are commonplace on such apps even though a banner saying screens are being monitored and “inappropriate content” is banned runs across.

The India head of a newly-launched app with Chinese connections, who has previously worked with ByteDance, told ThePrint, “Sometimes these apps intentionally keep the objectionable content because it’s the kind of content that will get more users. Algorithms will look for these content also.”

Dimple said broadcasters should not be judged for posting such content. “People have to do whatever it takes to make ends meet,” she added. “Some of these women are housewives or single mothers who see this as an option to earn enough money for their families.”

Naik claimed she wasn’t bothered by such content. “I don’t think it’s my concern if someone else wants [to post obscene content],” she said. “It’s their life, and their wish if they want to post sexy videos.”

Women broadcasters also face sexual harassment and lewd comments. “You have to be a strong woman to use this app…” said Dimple. “You have to be bold enough to handle people making requests for your phone number. Many women get scared when men rag them and say ‘open your legs’ and other things, so you need to be able to ignore it.”

TikTok told ThePrint that it was committed to providing a safe atmosphere for its users, citing options like account locks and blocking certain users. As for “obscene content”, the app said it provided users the option of flagging it.

Meanwhile, gutsy content producers like Dimple have embraced the onslaught and risks such as photo misuse, because higher user engagement means more fame and money.

“What difference does it make to me if someone steals my photo?” she said. “It only makes me more popular. There’s nothing to be scared of.”

More suggestive of a Ponzi scheme or a multi level marketing scheme.