New Delhi: Mehtab Alam, a madrasa teacher in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh, is doing the rounds with a list of 12 survey questions. Yogi Adityanath’s government’s hot-button madrasa survey, being conducted since August, aims to identify thousands of unregistered madrasas and their funding, but Alam says none of the 12 questions speak to the most pressing issue confronting madrasas today.

The teachers at the registered and so-called ‘modern madrasas’ — around 5,000 — have not been paid salaries for over four years. These are madrasas that teach science and maths in addition to Islamic studies. Instead, the most talked-about question in the survey list is about the source of funding for unregistered madrasas.

“Government keeps conducting investigations or surveys of madrasas. Why are they not paying salaries at modern madrasas?” Alam asks.

The National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) made the request for the survey after cases of violation of child rights, including sexual abuse, in madrasas of UP came to light. But the whole exercise has taken on a volatile and political overtone now.

The Yogi government’s survey has sent a chill across not only UP’s madrasas but also the Muslim community that says this is meant to harass them. AIMIM (All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen) leader Asaduddin Owaisi even called it a “mini NRC” exercise. Some madrasa managers talk in hushed whispers about the spectre of the feared bulldozers razing their institutions down.

The AIMPLB (All India Muslim Personal Law Board) asked why the Yogi government is not scrutinising gurukuls too. The Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind and Darul Uloom Deoband, however, welcomed the survey.

Madrasas have been a deeply political issue for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for many years now. They have been maligned as jihad-producing factories on TV channels, in political stump speeches and social media. And there have been repeated calls to modernise them with a regular curriculum and bring them under the scrutiny of governments.

But the biggest challenge confronting UP’s madrasas today are the salaries of teachers and a staggering dropout rate of students — from 3,17,046 students appearing in registered madrasa examinations in 2016 to 1,22,132 students in 2021, according to the UP Madarsa Board. That’s a 61 per cent drop in five years.

“If the government wants to conduct a survey a hundred times, then it should be done, but it should first give the salary of modern madrasa teachers,” says Ejaz Ahmad, president of the Islamic Madarsa Modernization Teachers Association.

The feared Question no. 9

In May 2022, two minor boys returned to their village, Barabanki, in iron shackles, claiming that they had been chained and ill-treated at a madrasa in Gosainganj 35 kilometres away. But the boys’ parents petitioned the police not to take any legal action against the maulana as they themselves had urged him to be strict with their children.

The UP State Commission for Protection of Child Rights (UPSCPCR) started probing the incident only to find more ‘worrying’ signs like unqualified teachers who were allegedly propagating radical thoughts. In its report to the government, the commission raised concerns over unrecognised madrasas and the abuse of children.

It provided the impetus for the survey.

The most rattling part of the survey is Question no. 9 — asking about the funding of unregistered madrasas. It is a query that strikes fear and conspiracies among the Muslim community.

A Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) leader explained that there are tens of thousands of madrasas that are operating without any checks. The district magistrates do not have them on their list, raising fears about unknown funding sources, how much is being spent on the school, and how much is stashed away.

Many in the community also admit that some madrasas are run inefficiently as individual fiefdoms and there is much corruption too. Government officials also argue that some madrasa funds come from outside India and can raise ‘national security’ concerns.

UP’s Minister of State for Minority Affairs Danish Azad Ansari said on ABP Live that the goal of the survey and the question about funds is not to intervene in the madrasa system but to provide better facilities for the students.

The fear in the madrasas is such that some even avoided participating in the survey.

Corruption is also a reason behind this.

One survey official tells why people have a problem with Question no. 9 — they don’t want to reveal the source of funding because their books aren’t clean. He adds that these unrecognised madrasas are mostly engaged in teaching Islamic philosophy exclusively.

Many who answered the question said they are getting money as zakat (Islamic charity), which has become a byword for non-transparent sources of unrecorded, informal funds.

Managing authorities of several madrasas took umbrage over this ‘uncharitable view’ of zakat, without which they would not be able to educate students. Smaller madrasas rely on community members, friends, and family. How is this different from any other charitable organisation, they ask.

“We use the zakat for the health and education of the children of madrasas. We have already informed the Intelligence Bureau and the government about our children and funds. Our entire fund is looked after by a chartered accountant. Everything is clear,” says Maulana Muzzamil Ali, manager of the Jamiat Tush Madrasa in Deoband.

A 2021 ORF report on India’s madrasas said that there is not enough transparency and accountability in funds received or spent by many unregistered madrasas. There is also a lack of a formal channel through which zakat is used.

“Zakat is not stolen,” says Mehtab Alam. But he admits that accountability is important as well. “Some people get zakat to spend on a hundred children, but then help only 20. It’s like taking away the right to education from other children,” he adds.

He acknowledges that madrasas may have a problem with Question no. 9 because some have shown their high expenses on paper. He explains that it often happens that madrasas take zakat but do not spend it on the students. Some institutions make them do domestic chores at the madrasas and their homes.

The land where these small and unregistered madrasas are built is also a “big issue” as it is not categorised as waqf, he adds. Waqf is any movable or immovable property donated by individuals for religious purposes. No single individual owns the property, which is then monitored by the local waqf board. Once a property is made ‘waqf’, madrasa owners lose their right over it. “That is why they are hesitant to register madrasas,” says the madrasa official.

“The purpose of madrasas is to educate poor children, but some people have made it their business due to which dropouts are occurring,” says Mufti Qasmi, a member of the Project Approval Board in Ministry of Minority Affairs.

UP Madarsa Board president, Iftikhar Javed, says earlier investigations showed that some madrasas exist just on paper. “The income of the people has increased, but the image of madrasas has remained the same,” he adds.

There are 16,500 recognised madrasas across UP, of which over 7,000 offer ‘modern’ education. Here, managements rely on school fees (anywhere between Rs 100 to Rs 400 a month or even less) and zakat to run the madrasa, but the government has no proprietary rights over them. That is not the case with aided madrasas, which are funded and controlled by the government. UP has 558 aided madrasas, many of which offer graduate and post-graduate courses.

It’s the ‘Islamic’, unregistered private madrasas that are the target of the government survey. The UP Madarsa Board estimates there are about 40,000 to 50,000 of them across the state.

Also read: The seed for Udaipur-like killings is sown in madrasas. Regulate teaching of theology

Where are the salaries for ‘modern’ teachers?

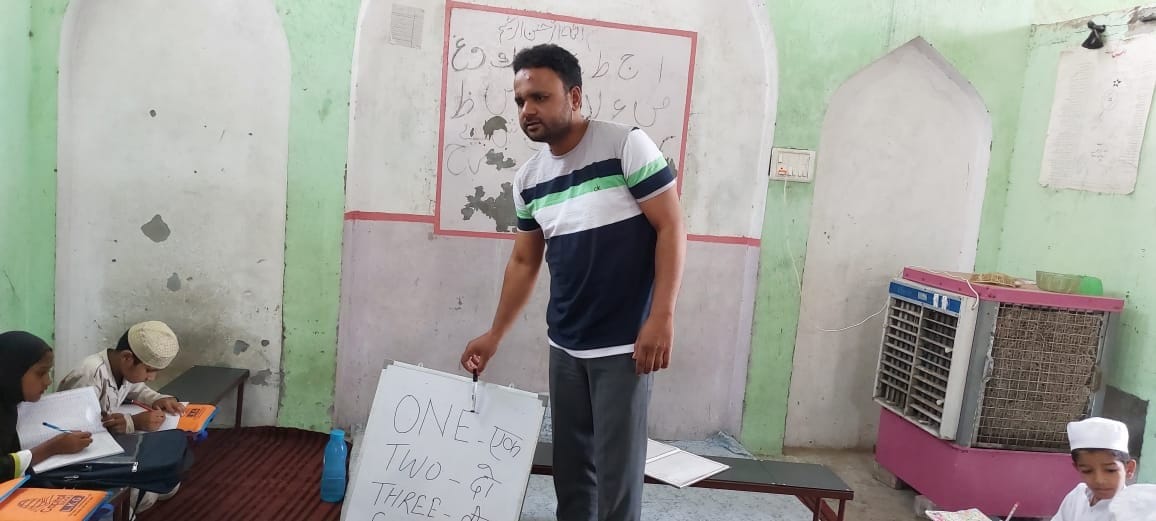

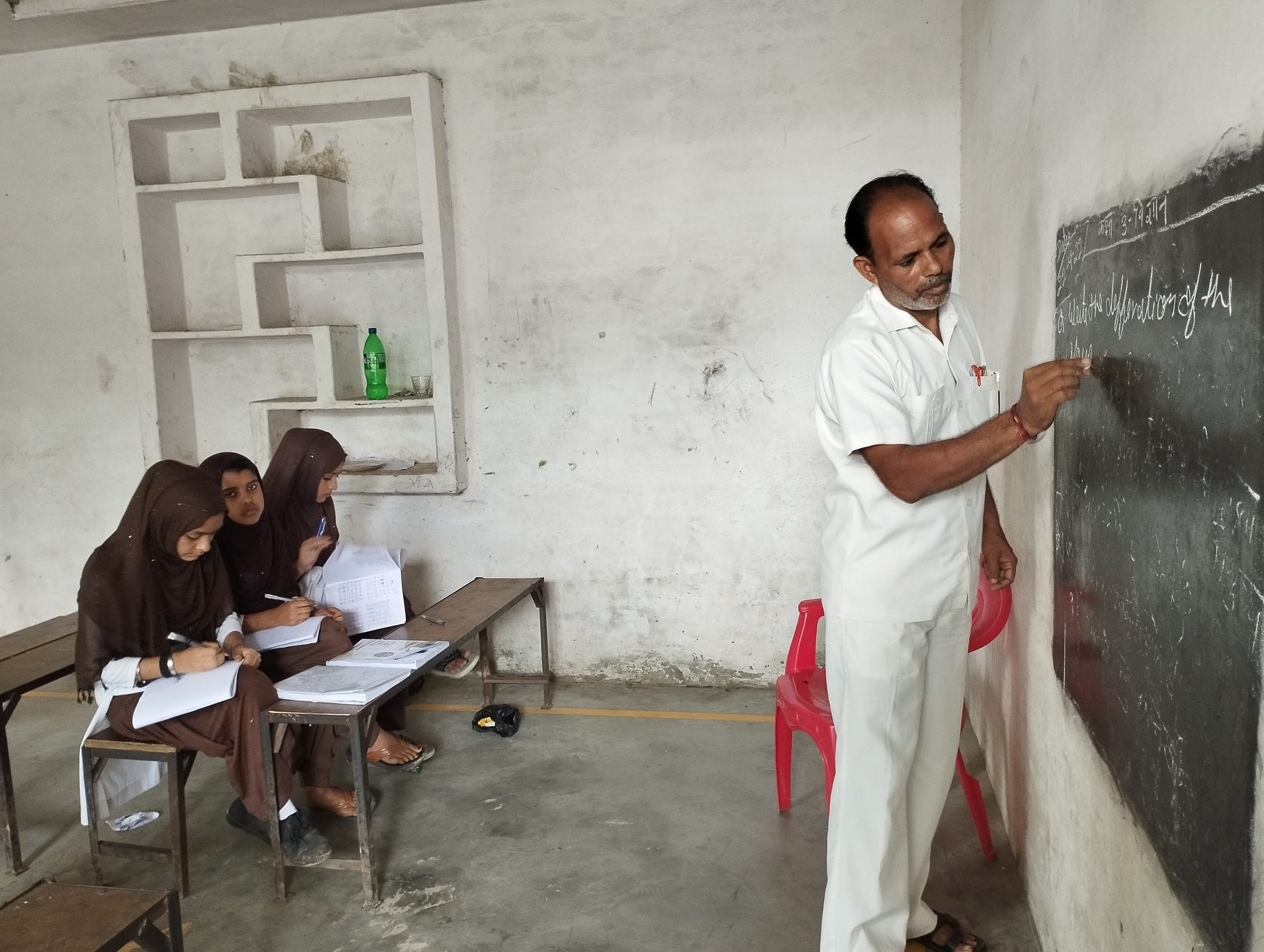

The phrase ‘modern madrasas’ may appear to be a contradiction in terms, but it is used widely in UP for madrasas that are registered, recognised by the government, and teach the regular curriculum — English, science, and maths — in addition to the Quran. The government appoints a fixed number of faculty members to teach these subjects and pays only their salaries. Other teachers and employees are paid by the management departments.

But the teachers haven’t been getting their salaries.

What’s more, the number of teachers paid under the Scheme for Providing Quality Education in Madrasas (SPQEM) across India has dropped from 50,957 in FY 2015-16 to 12,518 in FY 2017-18, shows data from a 2018 parliamentary standing committee report. During this same period, this figure fell to 10,724 from 37,824 in UP.

The scheme rolled out in 2009 and saw government-appointed teachers in madrasas. Since 2019, the Narendra Modi government has been paying only 60 per cent of their salaries; the rest is appointed by their respective state governments. The UP government pays an additional amount of Rs 2,000 per month to graduate teachers and Rs 3,000 to post-graduate teachers. But most teachers have not received their salaries.

Many teachers are struggling with debt and are forced to take tuitions, manual labour work, rickshaw driving, and selling vegetables to make ends meet. Now, the word has spread in the community too. And there are social problems that come with it.

No one wants to marry an unpaid teacher. “Whenever the girls’ families came to know that I was a modern madrasa teacher, they broke the talks for marriage,” says Abdul Rehman, general secretary of Madarsa Adhunikikaran Shikshak Ekta Samiti from Saharanpur. “They would say, ‘Your salary does not come. How will you take care of our daughter?’” adds Rehman.

Mehtab Alam and his wife Tamanna took extra private tuition classes, but the money was not enough. They finally pulled their children from a “good private school” and enrolled them into a government institution.

The teachers’ bodies have met Yogi Adityanath and former Union Minister Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi and current Union Minister for Minority Affairs Smriti Irani, but the salaries are still pending.

Technical glitches could well be the reason for the delay, at least according to some officials. “Last year, Rs 120 crore was released to pay the teachers, but due to technical errors and glitches, they have not been able to get the money,” said Mufti Qasmi.

“This problem has arisen due to discrepancies in the UDISE numbers of 1,559 madrasas,” he said, referring to the Unified District Information System for Education that helps organise and categorise all school data across India.

While keying in the numbers in the government portal, a single error, or even an incorrect numeral, can stall the system, claim teachers. If there is any discrepancy, the government refuses to pay the salary, but it has not been rectified yet, teachers say.

“The government entrusts us with all the responsibility like other government schools, whether it is to look after elections or exams. Then why don’t we get facilities and salaries like them?” Tamanna asks.

Also read: Not madrasas, not Pakistan terror camps, India’s blasphemy killers are products of toxic hate

A ‘dropout’ ecosystem

The double whammy of non-payment and student dropouts has left the madrasa ecosystem in a state of disarray.

Teachers say that most of the dropouts have taken place in unrecognised madrasas among poor or orphaned children. Most of the children of migrants have also missed their studies during the pandemic and the lockdown. Others have left their studies and started working.

According to Maulana Muzammil Ali, before the lockdown, more than 1,800 children used to study at the Madarsa Jamia Tush Sheikh Hussain Ahmed Al Madani in Deoband. Now, they’ve dropped to 1,200. And most of the dropouts are girls.

Not everyone agrees that the pandemic was the problem. It’s the “politicisation of madrasas” and “irresponsible attitude” of managers to blame, say teachers. A teacher, who does not want to reveal his name, says that politics is making some parents pull their children out of madrasas.

“Before the lockdown, 30 Hindu children used to study in our madrasa, but now, their number has come down to 10,” says Virendra, a Hindu teacher working at a madrasa. Other Hindu teachers, too, say that the cloud of communism has taken a toll on the mental health of the students and staff.

UP cabinet minister Dharmpal Singh told The Indian Express that the BJP wants to make madrasa students “ideal citizens, engineers, doctors not stone pelters”. Such comments are not rare. The word ‘madrasa’ has been demonised in popular imagination for some years now, not just in India but around the world as well.

“Madrasas are being maligned by politics, and this is reducing the enrollment of children. Parents are afraid to send their children to a madrasa,” Jarrar, a ‘modern’ teacher from Meerut, Laliyana village, says.

In a 2021 report by ORF, authors Rashid Kidwai and Ayjaz Wani wrote that 90 per cent of madrasa students belong to poor families, and many are struggling for funds. In 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi famously said that the government wants Muslim youth to have the Quran in one hand and a computer in the other, emphasising the need for rational and scientific education.

The report said that in states such as UP, Bihar, MP, Chattisgarh, Bengal, and Assam, many madrasas are state-funded. Yet, a large number of them are privately run. More madrasas in Kerala have adopted modern curriculums and teaching methods, while UP and Bihar lag behind.

Curriculum is a hotbed of controversy

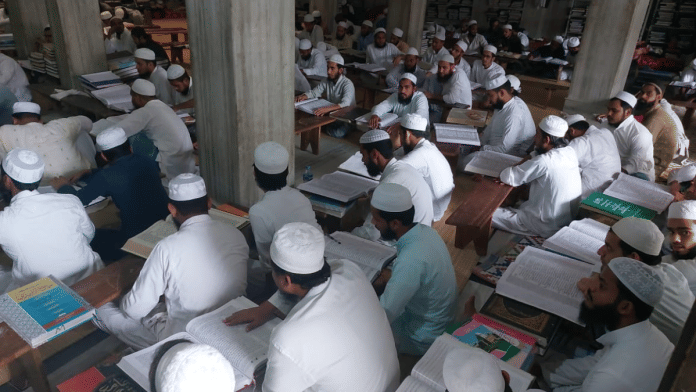

Around 30 students sit in an unregistered madrasa in the Khanqah area of Deoband. They are segregated — boys on one side and girls on the other. A maulana explains the meaning of Quranic verses.

The question of madrasa curriculum has always been a hotbed of controversy. In UP, the debate is over what to teach—the Bhagwat Gita, NCERT syllabus often become points of contention.

In 2018, the state government implemented the NCERT syllabus in madrasas, but the books have not been provided even now.

“Children studying in madrasas come from very poor families. They cannot buy books, and the government is not able to give them even NCERT books. Now how do these children get an education?” asks IMAAS (Islamic Madarsa Aadhunikikaran Shikshak Sangh) president Ejaz Ahmed.

Also read: Want UP-style madrasa surveys, mosque CCTVs in police control, says new Uttarakhand Waqf Board head

Madrasa vs madrasa

The UP government survey has also ripped open the intense competition among madrasas. There is much resentment not only toward Hindu gurukuls being kept out of scrutiny but also toward the registered and modern madrasas.

“Why do you need the details of our children only? See the condition of madrasas to which you (government) are giving funds. Do a survey of your other institutions as well,” says Maulana Ali. In the background, a maulana teaches the Quran to a class of 60 boys. As he speaks with a mic, his voice reverberates through the room.

Any mention of the survey, and everyone stiffens visibly. Conversations become stilted as maulanas express their fears of being targeted or profiled by the Yogi government. “The government claims it has the welfare of madrasas in mind. But there is a big difference between this government’s words and deeds. We have seen their attitude before. That’s why we doubt them,” says a madrasa official on the condition of anonymity.

Mufti Qasmi, though, says that madrasas need not fear the survey and should not be misled by disinformation and propaganda spread by politicians. Some cling to the hope that the survey will bring the government’s attention to issues such as the lack of buildings, water, furniture, and electricity in madrasas.

“Right now, the government has asked 12 questions. We have no problem with them. All these questions are fine. But if the government moves forward, interferes more or tries to harass us, we will take some strong action,” Maulana Ali told ThePrint.

Survey teams will submit their reports to district administration officials on 10 October. And everyone is on tenterhooks. “Most of the madrasas in this area are unrecognised. People are afraid that the police will raid them and then they will be tortured,” said a madrasa official from Deoband.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)