Kerala’s biggest art festival, the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is back this December after a gap of three years and is ready to take over the streets of Fort Kochi with eye-popping art installations, sculptures, paintings, and performance artworks. But beneath all the drama of the art world elitism, there is a dirty war over unpaid dues from the previous 2018-19 edition.

More than one crore rupees is owed to multiple contractors and vendors, and it is a story of alleged financial mismanagement, poor documentation, fund shortage, art snobbery and allegations of diversion of funds. The battle is being fought on the Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF) board, district court and Instagram.

The art festival’s budget in 2018 was Rs 30 crore. But it was run with a corpus of Rs 7 crore from the Kerala government and donations from corporate sponsors including Lulu, DLF and BMW. And at the heart of it all is a woman, Treessa Jaifer, the former finance chief of the KBF and a whistleblower of sorts.

“Those at the helm don’t know anything about fiscal responsibility or management. (They) throw money at anything that becomes a problem without thinking of the long-term,” said Treessa.

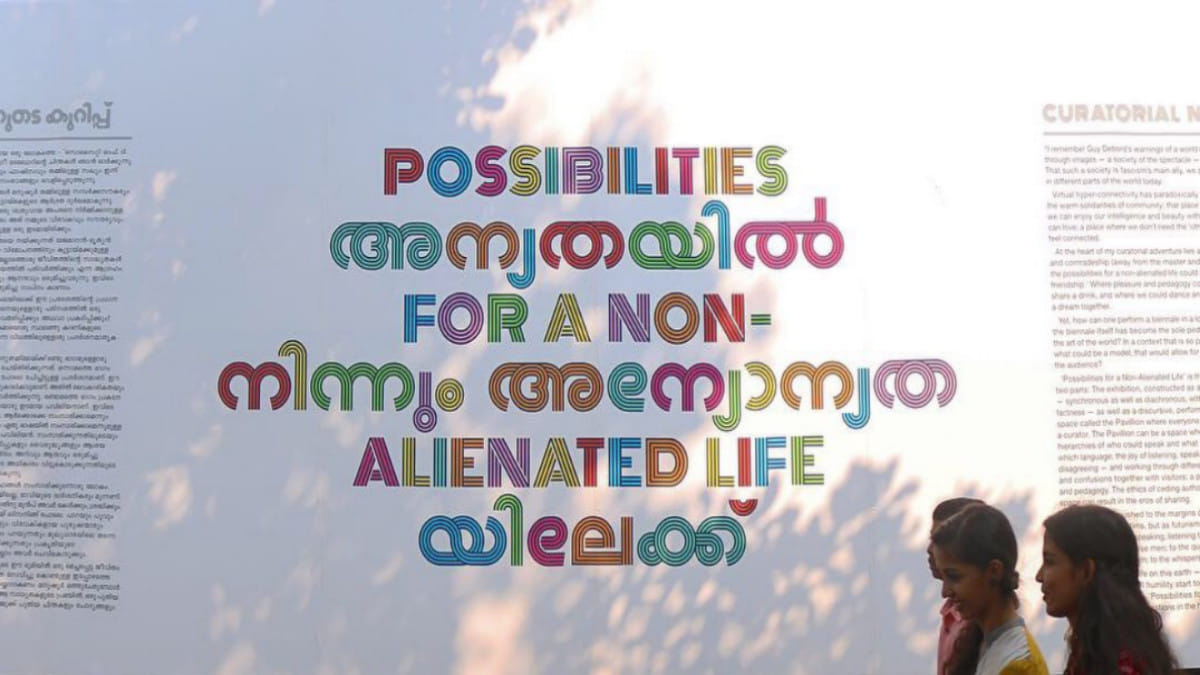

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is the first and only art festival of its kind in India. It is touted as the festival for the community, one that aims to make art democratic. The curatorial note by artist Anita Dube speaks of “warm solidarities of community” and a “politics of friendship”, “away from the master and slave model.”

But somewhere over the decade since its launch, the ‘people’s Biennale’ has lost its way. Behind the bold and provocative art and roster of famous artists are vendors and organisers hurling allegations against each other. In a state that prides itself on the rights of labourers and workers, KBF’s attitude is unacceptable.

“The Biennale was run like a personal project, not a multi-crore event that uses public money,” said Madhav Raman, principal architect and co-founder of Delhi-based Anagram Architects (AA).

Also read: Net-zero Picasso— museums are now rethinking art shows to cut climate impact

Social media exposé

The simmering discontent erupted on social media on 22 March 2019 with a new Instagram handle Justice From Biennale. Run by contractors, its first post was a portrait of a daily wage labourer, K.T. Shaji. The caption declared that Shaji worked for the Biennale from October to December 2018, but wasn’t paid his fees.

This was just the beginning. Over the next two months, the Instagram account posted images of several workers and projects detailing alleged financial mismanagement by the KBF.

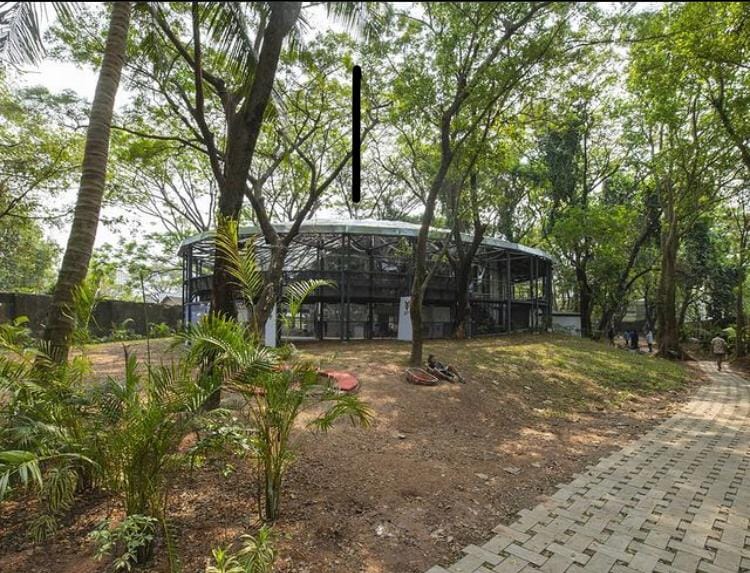

Thomas Clery Infrastructures and Developers (TCID), the main contractor of the event, oversaw 25 projects for KBF within two months in 2018. One of them was the all-important pavilion designed by Madhav’s Anagram Architects, an intricate structure with a bamboo roof.

“We lost Rs 77 lakh,” said Appu Thomas, director of TCID.

TCID sent a legal notice to KBF, which replied saying it had never given TCID any order, and that the work began on an informal agreement.

But KBF had already given TCID an advance payment of Rs 1 crore against its initial bills, said Treessa.

It is only a cliché that artists are not good at dealing with money. The intensely competitive world of high-priced contemporary art is proof that the cliché is just posturing. When payments are delayed, it’s hard to hide behind the artist tag.

In a 2018 internal communication, KBF said that the delay in payment arose as it had to “adhere to multiple auditing and compliances because we use public funds.” A copy of the email exchange is with ThePrint.

But the state government has absolved itself of all responsibility.

“Any delays would not have been government-related. Once they [KBF] give bills showing where the first instalment was spent, they get the next one and so on,” said a senior official with the state tourism department, which oversees fund allocation for KBF.

Also read: Why are women artists disappearing from museums? ‘Lack’ of works is a lie

Onus on contractors

The discontent evolved into divergent perspectives on what went wrong at India’s biggest art festival. In all this ballooning he said-she said, Tony Joseph, founder and principal architect at Stapati Architects, was assigned to mediate between the organisers and TCID in 2019, but the Covid pandemic took precedence and the issue fizzled out. But Joseph’s conclusion put the onus back on Appu and TCID.

“There was no mismanagement from the Biennale’s side,” Joseph told ThePrint.

“After looking at both sides, I don’t think KBF was in the wrong. Appu was young. He had to be better organised and a little more professional about the way they were doing things financially,” said Joseph, who is now a KBF trustee. In an event as big as the Biennale, there is bound to be confusion, which is why each contractor has to be “systematic,” Joseph added.

KBF also claimed that the revaluation of the “exorbitant bills” meant that TCID owed it Rs 24 lakh. But the foundation never pursued it.

When TCID first expressed unhappiness over the amount it was getting paid, the Biennale “graciously” agreed to hire an valuator. Appu alleges the re-evaluation was much below the amount he had claimed and did not consider the constrained time frame. “The landscaping for Cabral Yard [one of the locations of the Biennale] cost us Rs 3 lakh, but it was completely written off,” he alleged.

Appu recalled the amount of work involved in setting up South African artist Sue Williamson’s installation on the history of slavery, ‘Messages from the Atlantic Passage.’ It was an intricate display of hundreds of glass bottles intertwined with fishing nets hanging from the ceiling, dripping with water from top to bottom.

Appu claims the valuator never saw the “complicated” and “labour-intensive” process. “The valuator came only after everything was taken down,” and estimated the cost to be around Rs 75,000 when the actual bill was Rs 1.2 lakh, he alleged.

Sue Williamson told ThePrint that rather than ship her work from South Africa, the KBF said it would “employ people to remake my work in its entirety.” She was pleased it was providing local employment opportunities, but was not aware of the details. “If people were indeed not paid, that is most regrettable,” she said.

Financial mismanagement and delay in payments were not the only scandals the Biennale had to deal with. Co-founder and artist Riyas Komu had to exit from the organisation over allegations of sexual harassment. His departure impacted the event’s planning, said contractors. He was the de-facto organisational half of the co-founder duo. An internal complaints committee dropped the inquiry after several weeks in the absence of any official complaint. Komu was invited back but he says he declined the offer.

ThePrint reached out to co-founder Bose Krishnamachari, but he declined to comment.

Also read: Art tells stories of activism for generations. Climate gang defacing Van Gogh doesn’t get it

Plight of small-time vendors

From curators to contractors, it takes a village to host an extravaganza like the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. And TCID isn’t the only contractor nursing a grudge. Many smaller vendors also expressed anger over delayed payments. Some are still waiting for the money owed to them.

Antony Kadathus has been part of every Biennale since 2012, and was initially unwilling to take up a contract in 2018 because he was reeling from the financial devastation caused by the floods.

“Treessa madam being gone was also a factor. Neither Bose nor anyone else ever spoke to us. Komu would exchange pleasantries, but for all matters and purposes our point of contact was madam,” Antony said.

He eventually put aside his reservations, but regrets his decision to this day because he had to wage a legal battle for Rs 23 lakh owed to him.

Antony was assigned a myriad of tasks, anything that the artists required to realise their vision. He and his team polished floors, put together complicated structures of metal, and painted walls.

“I lost my father to cancer because I could not afford the treatment. Biennale did not pay me. After that I had nothing to lose,” he said.

Last year, Antony protested at the Lokame Tharavadu (‘The World is One Family’) exhibition organised by the KBF. Along with his associates—sub-contractors and employees—Antony stood outside the multi-artist exhibition in Alleppey in November 2021 holding a sign that read— ‘Recognise Bose as the cheat he is.’

Antony claimed that Bose exited the venue through the back when he found out about the protest.

“He is not brave enough to face me,” Antony said.

His threats and protests worked—to an extent. He received his money but over a long period of time and in installments of Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000. “I lost more money fighting them,” he said. He spent Rs 2 lakh on just the legal battle.

For their part, most artists are unaware of the tangled financial mess.

“The Biennale has a very well-respected panel of trustees who are holding down the fort. With such a large-scale operation, allegations of this kind are bound to surface but nothing has been proven,” said Suresh Jayaram, Bengaluru-based artist and curator. He disabuses the notion that artists lack financial competence to manage such events. “That’s a misconception. How else will art survive?” he said.

Also read: Indian artists are selling expensive NFT art. Are galleries ready?

Misuse of government funds

Former employees including an accounts manager are likely to disagree with Jayaram. They were the ones who had to deal with the clamour for payments from contractors while still ensuring that the ledger was in order. “They [KBF] bypassed all good accounting practices. When it was time for government audits and cost evaluations, we had to create backdated documents, which were filled with inaccurate information,” claimed an ex-accounts manager who said she “handled” this backdating.

Treesa alleged that to access government funds to pay Appu, the KBF would have to provide a purchase order. She asks that if these purchase/work orders were not issued, how could they access government funds.“The KBF claimed that they never gave an order to Appu, then how did they access the government funds through the treasury to initially pay Appu. They cannot do it without the relevant orders, this means they have given fake numbers to the treasury. This should be checked by the government,” said Treesa

But the tourism department official cited above said the bills passed scrutiny. “We never felt that the bills were fake. The funds are monitored by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG),” the official said.

This year, too, the Kerala government will provide monetary support to KBF. “We have received no complaints from contractors, and hence no investigation has been conducted. The matter is between the KBF and contractors, it is not our place to interfere,” the official added.

Feudal approach

The infamous elitism of the art world has crept into the “people’s Biennale” as well. In KBF’s case, the schism is not with the public, but the people working behind the scenes. Some go so far to describe the set up as “very feudal.”

Contractors took offence over the tone of KBF’s reply to TCID’s legal notice. The words reflect its elitism, they said. “… it is not within his (TCID) rank or station to preach to the trustees of KBF or to their representatives especially after enjoying their patronage,” read the reply.

The response riled Appu Thomas as well as Antony.

“I consider myself a better artist than Bose,” said Antony, explaining that he made the materials required for Bose’s installation while the artist had provided only the sketches.

The Instagram page and Appu’s efforts were active until May 2019, with posts about news reports and articles, cartoons, infographics and videos about the allegations. “I was already bleeding money when I was called to the Fort Kochi police station for an informal meeting. They said Bose wanted me to stop talking about the issue publicly,” Appu claimed. Three years later, KBF is yet to pay Appu, who has taken out multiple loans since then.

The Fort Kochi police said that without a petition or case number they cannot confirm that Appu had been called to the police station.

Many other contractors think the fight isn’t worth it, financially or mentally.

Also read: Jamini Roy, Ram Kumar and others featured at boutique art fair

Tracing back the steps

Treessa’s ousting stoked the flames. It brought an element of distrust among the various factions.

She had joined the KBF trust in 2011, the year it was set up by Bose and Riyas. By 2014 she rose the ranks to become its chief of finances. She steered the Biennale through some tough periods when it was dogged by controversy and financial crisis even before its first edition was launched.

In January 2013, a group of artists led by sculptor Kanayi Kunhiraman had filed a case in the Kerala High Court against the Biennale, alleging corruption before the first edition had begun. Government funds were blocked till the case was resolved in September 2013, after the first edition had taken place. Treessa said this led to the first financial crunch.

“Komu even sold off his properties to keep it going. And you won’t believe me but we had only Rs 500 in our bank account on the day we inaugurated the 2012 edition,” she said.

She would get calls from angry vendors every day. “I was threatened by gangsters,” she recalled.

But she kept the line of communication open with everyone and paid them after the funds were released. This, according to Antony—who was then owed Rs 14 lakh—is the only reason he kept coming back. He is not involved with the Biennale this year.

KBF had reached a comfortable financial position by 2016—according to Treessa—and a new CEO, Manju Sara Rajan, had been appointed. “But a power struggle had been brewing within the top management and the board of trustees,” she said.

Treessa was removed from her position in 2017 after Rajan and Bonny Thomas, treasurer and board member, accused her of incompetence. She was demoted to General Manager (Admin), and she withdrew from all financial responsibilities. To this day, the position remains empty.

In April 2018, Rajan resigned alleging financial incompetence and in an interview with The Times of India she claimed that Treessa “lit a bonfire” and destroyed financial documents. Rajan, however, declined to comment on the matter when ThePrint reached out to her.

An internal investigation on the alleged arson cleared Treessa of all wrongdoing.

Treessa made up her mind to leave when the approval of her maternity leave was delayed. But before that she was fired in September 2019. She filed a case against the KBF and trustees including Bose and Sunil in the Ernakulam District Court against the alleged discrimination she faced.

She accused KBF treasurer and board member Bonny Thomas of prejudice. “He wanted to take control of the event and push out everyone who wasn’t in agreement,” she alleged.

Factions have developed along the cracks. “The allegations are false. A small group of people wanted to malign and destroy the goodness of a great international programme,” said Murali Cheeroth, chairperson of the Kerala Lalithakala Akademi.

Need for accountants

Despite the long wait, many said that they don’t suspect any misconduct. The delay is not due to corruption but inefficiency, they say. Even contractors hold the same view. “Bose is not a bad person, he just doesn’t take the initiative to help people,” Appu said.

It isn’t as if the money stopped coming for the festival. It was mishandled.

The ex-accounts manager said that the accounts department was there for the sake of it. Both he and Treessa claimed that Bose and V. Sunil (then-trustee and current KBF advisor) would give the “go-ahead” without understanding the financial repercussions or consulting the department.

“The only time we were called on by the trustees was when they required people to field calls from angry vendors who were owed money, and there were a lot of them,” they claimed.

Madhav too said that what the KBF desperately needs is an “empowered CFO and a team of accountants, who can pull them back when required.”

“Such incompetence can lead to the squandering or at the least diluting of the event’s goodwill,” he added.

Also read: Art, anthropocentrism and a mega art fair

Subdued year

The new edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is barely a month away, and work is finally picking up to transform Fort Kochi once again, the beating heart of the festival, into a giant walk-through open art gallery. Art will finally uncurl itself from the pandemic slumber of three years.

This year, Annah Chakola, designer and founder of the label Annahmol, has been asked to curate the design shop. She is working on a tight deadline, but she’s thrilled. “Anything of this scale is always a big task but nothing is impossible. It’s inspiring and as a resident of Kochi, I want to do whatever I can to contribute to its success,” she said.

She has “full faith” in Bose and the team. “What they have been able to achieve in the past editions, overcoming huge odds, has been nothing short of incredible. I do believe it is the ‘people’s Biennale’ and warrants a spirit of cooperation and participation,” she added.

But the thrum of activity is more subdued this year. By October 2018, the Biennale’s Instagram handle was a visual feast with promotional materials and behind-the-scenes images of work underway.

This time, with the festival slated to open on 12 December, the posts are still calling for volunteers and “art mediators”.

The show must go on. But as Pablo Picasso said ‘art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.” The Kochi Biennale has a lot to dust off.

This article has been updated to include the response from Riyas Komu, one of the founders of KBF.

The story has been updated to maintain accuracy of quotes.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)