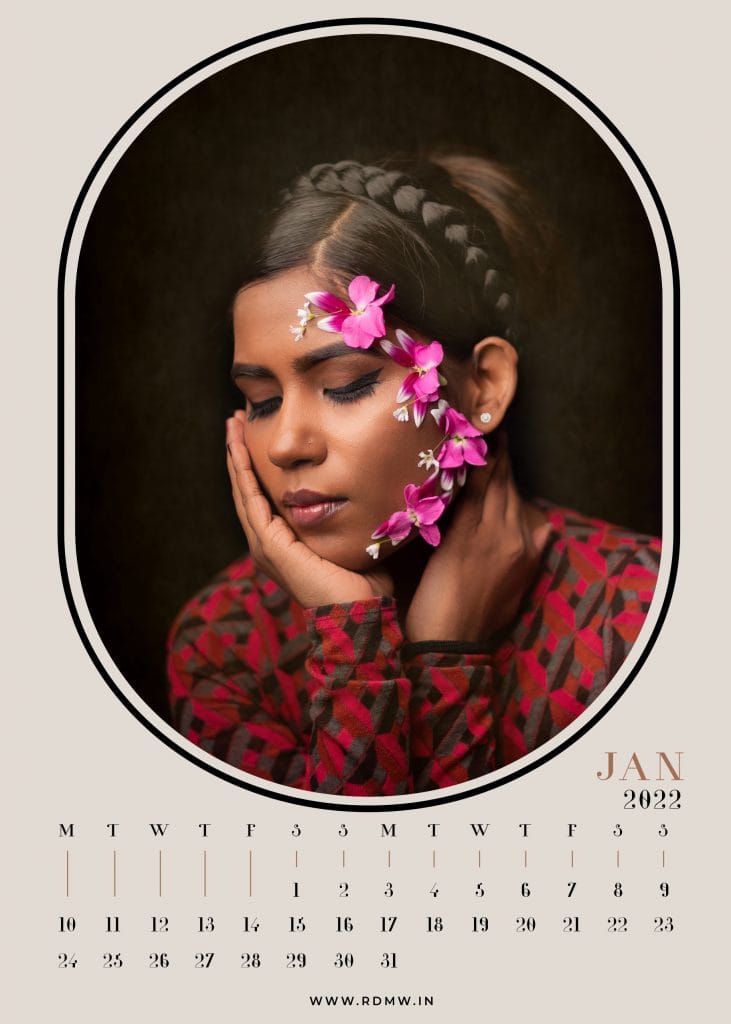

Oddity 2022 is a calendar that celebrates inclusivity and diversity in India by bringing together 12 people from diverse and marginalised castes, classes and genders, including trans-queer persons and people with disabilities. The purpose of the calendar, shot by Delhi-based photographer Rishab Dahiya, is to defy the ‘beauty standards’ of society that he considers casteist, classist, Euro-centric, homophobic, transphobic, and fatphobic.

Dahiya says, “We need to rethink how beauty is perceived and normalise people who are considered ‘odd’ because they do not fit into certain limiting ‘aesthetics’. We need to have icons who look like everyday, normal people in a country that is so diverse.”

Dahiya’s first attempt at ‘normalising’ beauty standards was in 2020, when he, along with Purva Mittal, launched Oddity and featured six people with special needs on a desktop calendar, and in 2021, he decided to diversify further.

Also Read: Cultural diversity can drive economies. Here are lessons from India and South Asia

Calendars, models and celebrities

Not long ago, calendars were the default in nearly all Indian households and were proudly displayed in drawing rooms or study tables. Over time, digitisation and phones have made a physical calendar obsolete.

There has been, however, a surge in the production of exclusive, curated calendars meant for the ultra-rich where only the ‘best’ can hope to feature. And the ‘best’ means those who fit certain stereotypes of beauty.

One of the pioneers in India in these exclusively created calendars was the United Breweries Group, which created the famous Kingfisher Calendar in 2003. It’s not just a calendar but one of India’s most prestigious modelling assignments and has played a part in the launch of actors like Katrina Kaif, Deepika Padukone and model Angela Jonsson to stardom.

The other famous calendar shoot is that of Dabboo Ratnani’s. If the Kingfisher calendar is for models, this one is for Bollywood celebrities, and it is considered a privilege to be shot by the ace photographer who has been doing this for 25 years now.

Also Read: One step India can take to make private sector jobs more inclusive. And it’s not quota

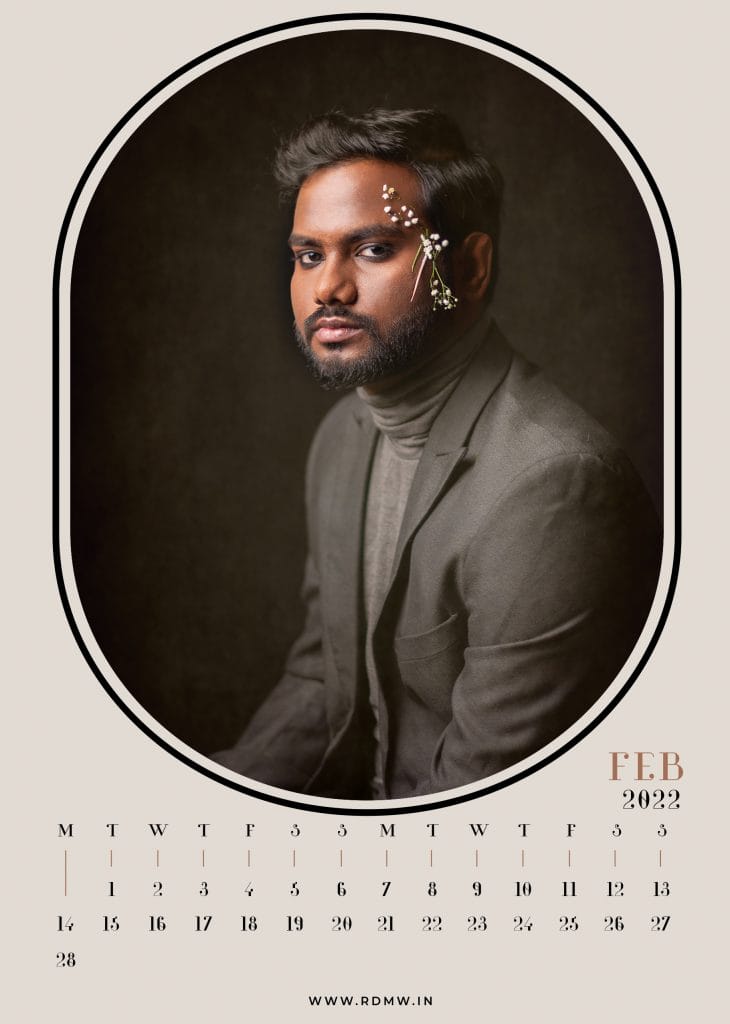

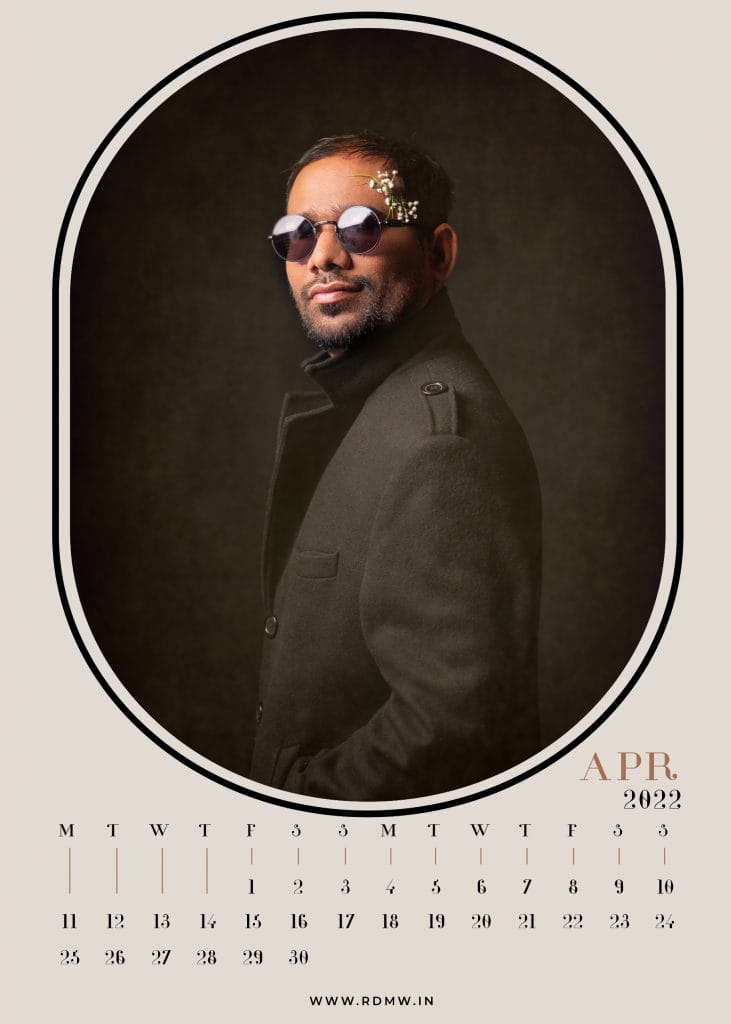

The ‘Odd’ people

Raam Guru, who is a part of Oddity, says, “When they applied makeup on me, they told me what products they were using and what was being done to my face”. For Guru, who has been blind since birth, this was an important part of feeling included not simply in the calendar, but also within a society that still remains clueless regarding its approach to disability. A first-year PhD student at Jawaharlal University, Guru says that inclusion in a space that feels exclusive, like modelling, would aid in bringing greater visibility to disabled people and their issues.

Kamna, an assistant professor at Delhi University, says, “My skin tone has always raised questions about my caste-identity, sometimes directly and sometimes in oblique ways. I experienced untouchability because of my skin colour. In order to bring the gaze outward, I started modelling.”

Dahiya, who works as a fashion photographer and has worked with premium brands like FBB Femina Miss India, Times Music and Lakme Fashion Week, says that he wanted to create a space where representation matters: “I found most of the people in the calendar through Clubhouse, and closely interacted with them”.

He wanted the shoot to be an experience that made them feel comfortable and express themselves the way they are.

Also Read: Human Libraries can break down prejudices, foster diversity and inclusion. Here’s how

Inclusive spaces

In 2020, a desktop calendar by The Art Sanctuary, Bengaluru, featured photographs clicked by eight photographers with intellectual disabilities. But the numbers are still pretty dismal.

Tokenism is often an issue that occurs in the name of inclusivity and representation. And Kamna agrees that one person is not enough.

Recently, when Harnaaz Sandhu was crowned Miss Universe, the question that still remained was if we have progressed towards a more inclusive society, especially in India. When it comes to modelling, we still look for taller models, despite the average height of Indian women being 5.3 feet. One can still opt for print modelling if they are not tall enough, but in the world of ramp modelling, a certain height, body type and weight are still considered ‘desirable’.

While there have been attempts to break stereotypes — from 52-year-old lingerie model Geeta J to Mopna Varonica Campbell, a plus-sized transgender model — once the glass ceiling is broken, that is where it ends. Others do not get access or entry, and we ultimately circle back to the same stereotypes, be it skin colour, age, height or body type.

(Edited by Srinjoy Dey)