Bastara/Haryana: After a long wait, Haryana held its panchayat elections in November 2022. Democracy begins with panchayats, Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar had said then. Today, the panchayat heads are at war with the Khattar government over the new e-tender policy.

Representatives of the Bastara village in the state’s Karnal district had drawn up ambitious plans back in December 2022. Drainage pipelines needed to be urgently installed, boundary walls for crematoriums had to be built, government schools had to be spruced up, and new community centres opened. Some families queued up to get their pension and ration cards too.

But now, all the plans lie in wait because Khattar wants to end corruption in village panchayats. E-tendering of contractors for large-scale public works is his new mantra. Village heads following the old patronage system and working with known contractors lament that their positions hold no real meaning anymore.

“An engineer will tell us [how to do] our jobs? They are ridiculing us by attacking our autonomy and taking away our constitutional rights. There are so many castes in a village, and who better than the sarpanch knows where to build a street or drainage?” said Ranbir Singh Samain, the president of the Sarpanch Association of Haryana (SAH) at the Panchkula-Chandigarh border before he was being detained by the police on 4 March.

Also read: Days after lathicharge, Haryana sarpanches continue stir against e-tendering rule: ‘Won’t bow down’

The e-tender turn

Khattar introduced the e-tendering policy in February 2021 with the amendment of Rule 134 under the Panchayati Raj Institution (PRI) Act. But nobody gave it much thought at the time because the term of the panchayat had ended that month itself, and there were no elections in sight due to the Covid-19 pandemic and other legal tangles related to reservation for women and Backward Classes.

The policy’s claims to work toward accountability, transparency, and quality infrastructure projects were ignored—until two months ago when the new sarpanches were elected to power. They were ready to dip into the funds promised to them by the Khattar government. After all, the CM had announced Rs 300 crore for “unanimously elected representatives”, and the transfer of Rs 1,100 crore into the accounts of PRIs for development works.

Ironically, while making these announcements, a 12 January press release from the CM’s office made no mention of e-tendering. “It has been decided that Panchayat, Panchayat Samiti and Zilla Parishad will be able to prepare their own budget every year and use the funds themselves for the development of their area. The government will not interfere in this work,” stated the release.

Later, when sarpanches started to plan projects, they discovered how drastically e-tendering would limit their spending powers. Under the policy, a sarpanch can execute a project only if it costs under Rs 2 lakh. Any project costing more than that will be done through the e-tendering process.

Suresh Kumar Fauji, the Bastara village sarpanch, changed his views from supporting the policy to opposing it in three months.

“Initially, I supported the policy. But when I issued three e-tenders for my village and faced problems, I changed my stance,” Fauji told ThePrint.

Also read: ‘Will give befitting reply’: Sarpanches intensify stir against Khattar govt after lathi charge

Winter of discontent

Starting from January and throughout February, sarpanches organised meetings at block and district levels to go up in arms against the Khattar government. Village after village began mobilising citizens, and protests spread across Haryana. A winter of discontent across rural Haryana culminated in a mass agitation in spring. On 1 March, the sarpanch body, including Fauji, brimming with anger, marched toward the CM’s residence in Chandigarh to protest. “Commission khori” became the catchphrase for both the Haryana government and sarpanch body — one wants to eliminate it through the e-tender policy and the other says it will be introduced through the initiative.

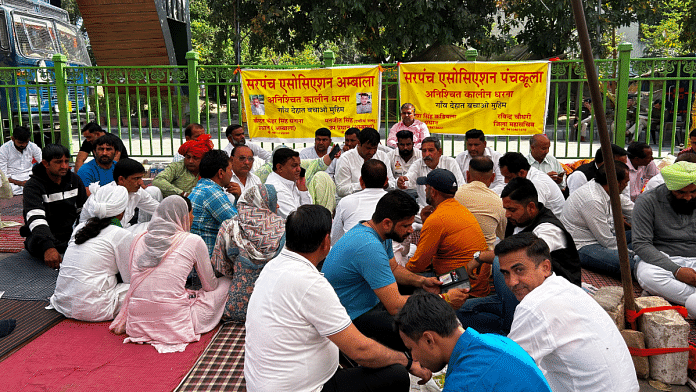

The police retaliated with a lathi charge. In response, more than 1,000 sarpanches—affiliated with the SAH—staged massive protests that spilt onto the Panchkula-Chandigarh border. They were forcibly evicted; some were detained following a court order.

The sarpanches have returned to their villages, but with support from the Congress and Indian National Lok Dal (INLD), they have vowed not to give up their agitation until the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government rolls back the e-tendering policy. The events of 9 March will unfold the future course of action—it is when Khattar and SAH representatives will start a dialogue.

Emasculation of power?

A few metres away from Fauji’s house, tractors and JCBs are digging a prominent pond in the village. But this pond is of the least priority to the villagers who want Fauji to tackle the bad drainage system first.

“This project is under the Rs 2 lakh budget, so I can execute it,” Fauji says. But he knows it will earn him no brownie points with the villagers who voted him into power.

“The two major drainage pipelines are the need of the hour, but I can’t start the project as they are stuck in the e-tender policy,” Fauji explains. Having failed to execute three projects in the village earlier, the sarpanch had to undertake the process of e-tendering all over again.

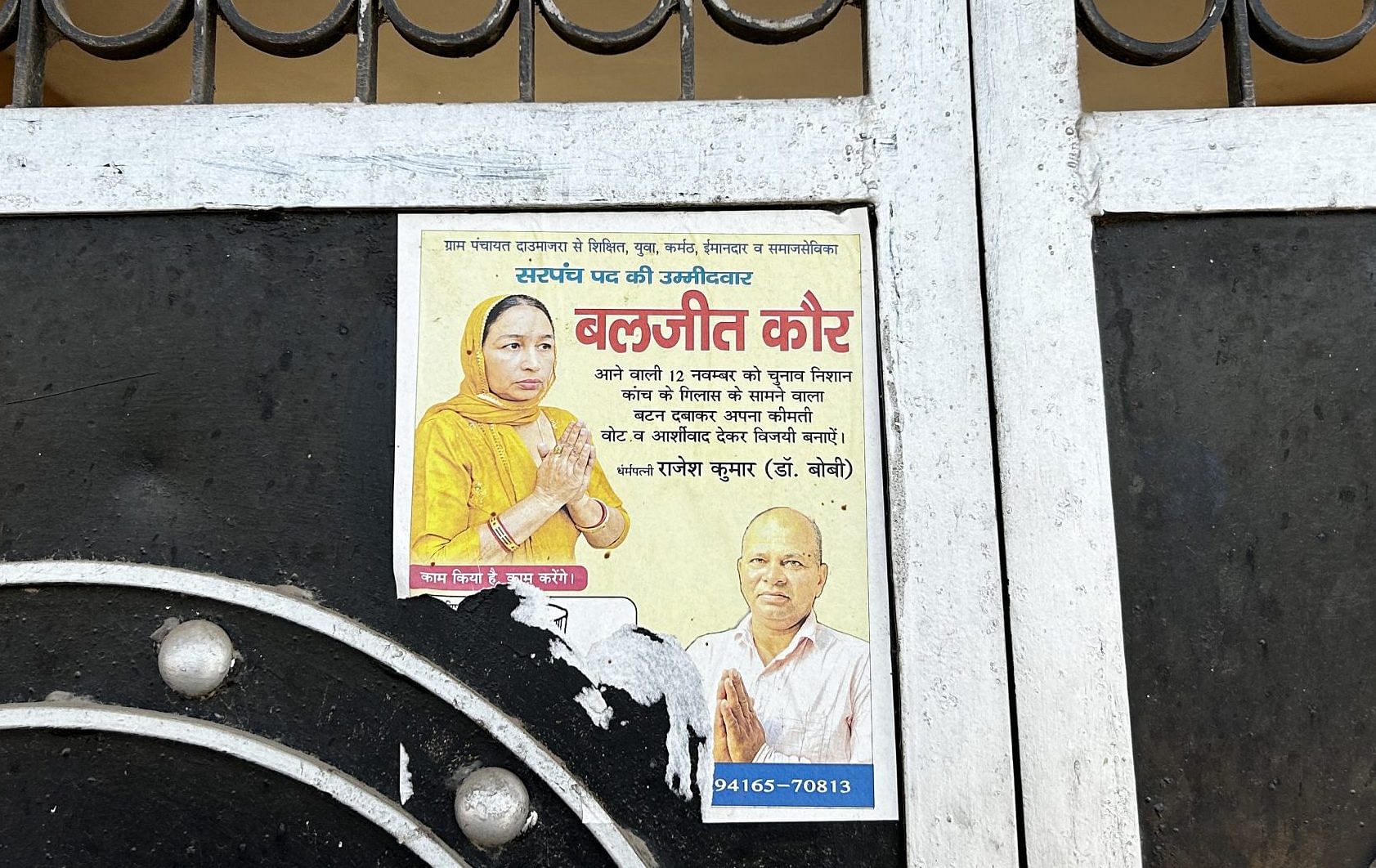

In Kurukshetra’s Dau Majra village, Baljit Kaur “invested” all her savings into her election campaign. The gamble paid off — she won the coveted sarpanch seat, but, like Fauji, she is depressed, disillusioned, and disgruntled now. The e-tender policy has emasculated their roles as village heads.

“We don’t have [the] power to decide which street needs roads and which needs drainage,” she says.

The SAH says the e-tendering policy is a war against village culture that will destabilise their traditional ways. One of the main demands at the Panchkula protest was “Gaanv dehat bachao muhim (Save the village).”

Village heads are apprehensive about another issue — a state government-appointed engineer dictating where and how they should direct funds for projects. Samain denounced this as a centralisation of power. In a report in The Indian Express, he pointed out that with this policy, the government needs to take “22 executive engineers of the state’s 22 districts into confidence to control the entire tendering system of nearly 6,200 village panchayats.”

Another protester called the government a “chor” (thief) for eyeing the Rs 1,100 crore Khattar promised for PRIs.

“They need to fund their political campaigns in the next assembly elections, so they need to bring their people into the development projects,” Sudhir Buana, a village head from the Jind district, alleges.

However, Haryana Development and Panchayat Minister Devender Singh Babli calls these accusations ‘baseless’. He says that the government has created an online portal where the village heads need to upload the details of the development projects.

He says around 2,900 development works costing less than Rs 2 lakh have already been started in various villages.

“Around 600 contractors have been registered on the portal. We have also reduced the 55-day timeline to a total [of] 21 days to speed [up] the work,” he says.

Then vs now

Mewa Singh, 60, who served as Bastara village sarpanch between 2016 and 2021, calls these protests a farce. During his tenure, he constructed a water tank, banquet halls, a park and panchayat bhawan, he told ThePrint.

“Earlier, the village head would at least take a commission of 30-40 per cent in development works. So, if it’s a Rs 20 lakh project, he would be pocketing Rs 8-10 lakh,” he says, adding that the protests have no support among villagers.

The older system required no such accountability or transparency. Sarpanches would cherry-pick labourers and contractors for the projects—there were no objective metrics.

“If I had to build banquet halls in the gram panchayats, I would give employment to the labourers of my village. I would bring my known contractor. There was no competition for being the best,” he says.

While the e-tender policy won’t take away the jobs of local workers, it will inject objective and competitive standards. Sarpanches say their power and authority will take a hit as the process becomes largely digitalised.

The new e-tender policy will be an open and fair game where anyone can participate. The e-tendering process will have an open-bid platform where any registered user can participate; the best offer will win the rights to the project.

Bajinder Singh, a contractor who has worked with many sarpanches in the Karnal district in the past, is confused by the new system but says that it doesn’t mean a loss of work.

“We can still register ourselves on the portal and get work in the panchayat. It is a loss for the sarpanch whose commission is going to be cut,” he adds.

Back in the Ajraheri village, election posters are still plastered on the walls of offices and bhawans. The colourful photos of campaigners asking for votes with folded hands have dulled over the months. And the malodorous drains nearby have become potent and pungent as temperatures—and tempers—rise.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)