Bollywood might be greying under the weight of tired superstars from the 1990s, but South Indian cinema has never been more vibrant. In just the last few years, actors from industries in the South have cemented their gold status—Dulquer Salmaan, Nayanthara, Vijay Deverakonda, Sai Pallavi, Samantha Ruth Prabhu—the list goes on.

It isn’t only North India that’s finally woken up to South Indian cinema and television — content from the South is officially making a global impact. And the numbers show it.

Minnal Murali was on Netflix’s Top 10 list in over 30 countries, from Argentina to Saudi Arabia. Another film on Netflix, Navarasa, drew 40 per cent of its audience from outside India in the first week of its release. Amazon Prime told ThePrint that 50 per cent of their viewership for Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada films now comes from outside South India, while 15-20 per cent comes from outside the country. They’re already capitalising on this—their new thriller Suzhal: The Vortex is the first long-form scripted Indian original show that Amazon has released—and it’s in Tamil.

Industry insiders, film critics, and media business analysts all agree on the fact that South Indian content is not just experiencing a jump in viewership, but also raking in the big bucks. Take blockbusters KGF 2 and RRR—both of which came out earlier this year, and crossed the Rs 1,100 and Rs 1,240 crore mark worldwide respectively. Bollywood collections simply pale in comparison: this year’s megahits Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2 and Gangubai Kathiawadi raked in only Rs 262 crore and Rs 209 crore each, says IMDb. The year’s biggest Hindi commercial success, Kashmir Files, made Rs 340 crore globally.

Bollywood has also left a void that other industries are more than willing to fill. The Bollywood of the 1990s shone so bright that new stars had to jostle for space—but now, the epic star-driven blockbusters that draw the most crowds are films like Baahubali and KGF. Both were record-breaking films from the South, and their Hindi-dubbed sequels earned around Rs 250 crore during opening week. Clearly, North India is watching.

“Back-to-back successes for movies from the South have led to immense traction on every platform,” said Ravi Kottarakara, general secretary of the Film Federation of India. “Although this is not a new phenomenon, whenever I access an OTT platform, I see more films and series from the South than others,” he told ThePrint.

And the losing quest for a Bollywood star—as well as the successes of Tollywood, Kollywood and Mollywood—have helped the South Indian cinema phenomenon.

Move over, Bollywood

It isn’t just that South Indian stars are becoming more and more mainstream. It’s also the fact that the South Indian film industries are staying up-to-date with cultural and technological trends.

Social media has become immensely relevant after the onset of Covid, and industry folks note that the way a film is marketed and distributed has fundamentally shifted—OTT platforms and theatrical releases are here to coexist.

“South Indian cinema has a wide variety of offerings,” said Mohamed Shafeeq Karinkurayil, an Assistant Professor who teaches film and cultural studies at the Manipal Centre for Humanities.

“Some of it, such as the domestic thriller or drama, has international appeal because it already shares a Western language of films,” Karinkurayil told ThePrint. “Others, such as the star-driven big-budget ones, appeal as a continuity of an established mode of narration in Indian mainstream cinema while updating it on the technological front. The appeal of these offerings is different, but the appeal is there,” he added.

Also, according to Karinkurayil, South Indian cinema has been so prolific that it’s kept up with real-time global developments. Across all four industries, South Indian films seem to offer a wider range of themes and genres.

“It is perhaps only Malayalam cinema that has factored in Covid-19 as a historical time we are going through,” he said. “The virus features as a time marker in films like Joji and Aarkkariyaam, and this is bound to strike a chord with the audience.”

Also read: ‘They are so gay’ fans perplexed by Western audience’s perception of ‘RRR’ as queer story

Moving beyond usual themes

The Bollywood we’re used to tells us big, grand, sweeping stories of love and loss that let us escape into worlds we’re not used to. Films today transport us to more specific contexts— not just because they have to compete with all the other content available, but also because it provides the space for expressions of multiple identities.

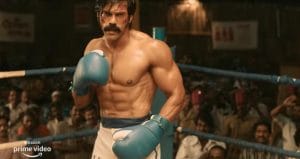

When ThePrint spoke to a high-ranking producer in the Tamil film industry, who did not wish to be identified, the person spoke of content that is “rooted” or “native” to the land or that which discusses a specific context that is doing well. “Take Pa. Ranjith’s Sarpatta Parambarai that was released during the pandemic on Amazon Prime. It did really well because it was about Chennai, about boxing, and rooted in a specific time period and culture. People went gaga over it.”

A big change compared to Bollywood is also looking at issues through the eyes of women, the producer said. “In Tamil cinema, though we welcome good content, we tend to move towards stars. Stars backed by good content is a winning combo,” the producer said. “But people are also noticing that just because you have a star, you can’t make something completely illogical. There is pressure on even stars to choose better content or diversify in their choices,” the producer added.

Filmmaker and professor K Hariharan listed three films—Kadaisi Vivasayi, Saani Kaayidham and Sethuthumaan—that released in the last three years, as “brilliant” examples of Tamil cinema. “All these films are very interesting since they are dealing with rural Tamil Nadu with a very different lens,” he told ThePrint. “The fact that these three films were made, funds were raised, and the films were released, all takes guts to do something like this.”

Hariharan draws a distinction between the violence portrayed on screen in films like RRR, KGF and Vikram with the films he listed. “In these (smaller) films, there is a larger social malaise that is palpable, that is defined, clearly elucidated. In some of these popular films, it is hard to fully understand the conflict,” he said.

At the end of the day though, it is entertainment that sells, said the producer. “If you think about it, S Shankar was the original person who made films like Baahubali and KGF with his films.” the person said. “You have to remember that Shankar was the first filmmaker in India to put the seven wonders of the world in one song!”

Also read: Bigger, more profitable — How South Indian film industry took pole position from Bollywood

Decoding OTT strategy

OTT platforms haven’t forgotten that entertainment does, in fact, sell.

Netflix and Amazon might be the preferred choice for films and TV shows with serious social themes, but the platforms are also counterbalancing this with blockbusters that hold high production value. And there isn’t necessarily a binary between socially conscious films and blockbusters for South Indian films.

Netflix, for example, has had a steady stream of ‘vernacular’ films in their Top 10—and several of them are blockbusters like RRR, Minnal Murali, Kurup, and Navarasa.

With the changing viewership patterns and improvement in revenues, platforms are gradually becoming liberal in allotting space to films that ensure visible success. Sources from one of the major OTT platforms have suggested that data always indicated an upward movement in earnings if “diverse and entertaining films” across “genres and languages” are nudged further.

However, this strategy is now used to meet revenue gaps that were caused before and after the pandemic.

In 2021, Netflix’s 28 Indian original titles were across seven languages, eight formats and 11 genres across films, series, comedy, reality and documentaries. According to Monika Shergill, vice-president of content at Netflix India, dubbing and subtitles have only helped these titles reach a much wider audience.

Amazon Prime, too, is following the same blueprint. While the aim is to open a “window into the multiple cultures that exist within and outside the country,” Amazon Prime told ThePrint that their content strategy will also hinge on replicating the success of films or series from the Southern parts of the country.

Also read: Bollywood stars are all the rage at Cannes, but why does India not have more films competing?

Changing audiences, expectations

OTT platforms have also begun collaborating with directors and performers from different backgrounds—especially the ones who belong to the ‘non-Hindi’ genres. Amazon intends to launch 37 original series and movies across Tamil, Telugu and Hindi over the next two years, and Netflix wants to bring together “a new generation of talent” to push out content almost every month.

A part of the numbers game is responding to changing audiences. A new formula seems to be casting major stars from the 1990s—who have retained their fan base—in new, experimental films.

The year in which things changed in Kerala was 2011, according to Karinkurayil, because that was the year “different” films began to come out—like Traffic, Chappa Kurish, and Salt n’ Pepper. “The movies moved away from established stars and narrative modes, and chose interpersonal relations in their intensity over wider social canvas,” he said.

Ultimately, this shift led to genres that focus on personalities, leading to a rise in detective films and domestic dramas.

“Though initially the new crowd was derogatorily called ‘new generation,’ it has been a dynamic industry,” said Karinkurayil. “But at times, not always, the stars have had to depend on the nostalgia effect too.”

The “new crowd” is also a result of the forced introspection that the Kerala film industry is doing.

The industry drew its battle lines after actor Dileep was accused of sexually assaulting an actress in 2017. Those who took the actress’ side were practically sidelined and denied roles—the actress herself is only making her comeback in Malayalam cinema in 2022, five years after the assault happened.

The incident also made industry insiders re-evaluate workplace practices that enforce sexism. Women in the Kerala film industry formed the Women in Cinema Collective, which advocates for grievance redressal and non-discriminatory, safe and hygienic workplaces.

Also read: Films, YouTube, Ambedkar — Pa Ranjith is building a new world and it won’t be sidelined

The power of a good story

North India might finally be waking up to South Indian cinema, but industry folks have always known the power of a good story.

And good stories can be told in any language. Purohit told ThePrint that local language cinema has a lot to offer not just to Indian audiences but also to the rest of the world. “Customer choices are evolving,” she added. “They are open to experimentation, want variety, and are willing to venture out of their comfort of familiarity and go in search of good stories, with compelling, nuanced narratives.”

Shergill said that Netflix’s main objective will always be to “entertain” members and to bring out “universal” stories.

“Over the years, we have learnt that good stories travel, and can transcend the barriers of language and geography,” added Purohit, and rightfully so. South Indian films have clearly hit the nail on its head.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)