New Delhi: In Karachi, a theatre group staged a quiet revolution. With saffron robes, AI projections, and a mostly Muslim cast, for the first time in Pakistan’s history, the Ramayana was performed as a full-fledged play. It was a hit— and no one protested.

At the centre of this theatrical first is Yogeshwar Karera, a 30-year-old director and co-founder of the Mauj Collective, the theatre group behind the play. A self-described “mythology nerd”, he didn’t know he was making history until a musician backstage pointed out that this is the first time Ramayana has been staged like this in Pakistan.

“We were just trying to make something beautiful. Turns out, it was also historic,” Karera told ThePrint.

For him, it was simple. Fascinated by mythology from a young age, having grown up on Dayanand Sagar’s Ramayan, inspired by Girish Karnad’s Hayavadana, he just wanted to translate the magic of the Ramayana that he grew up watching on TV to the stage.

“I wanted to recreate what I felt as a kid, give the audience that same sense of wonder, but on stage, not just a TV screen,” he said.

For Rana Kazmi, who is the producer of the play and also plays the role of Sita, “it’s the colour, the magic, the universal values” of the play that drew her to it. Her connection is also more pop than puranic. She grew up on a heavy dose of Bollywood, Star Plus and Tulsi, Smriti Irani’s character from Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi. Ramayana was no different.

Karera quipped that he wanted to stage a Tulsi-style entrance for Sita. “In the part where you pour water into the plant, I wanted the show’s background music”.

“You should have done it!” Kazmi said.

Beyond borders

Founded in 2024 by three National Academy of Performing Arts graduates, Karera, Kazmi and Sana Toaha, Mauj Collective focuses on experimental, emotionally honest theatre. Their past works deal with a range of topics from climate change to AI companionship. Their debut play Lungs, tackled the dilemma of parenthood in an age of ecological collapse. Night Mother navigated suicide, epilepsy, and maternal grief. Another, Rumi Aur Main, imagined a woman forming a bond with an AI caretaker—much like the 2013 film Her, but in Urdu.

“We’re not about one theme. We ask, ‘What stories do we need to tell right now?’ Sometimes that’s about a robot. Sometimes that’s about Ram,” Kazmi said.

The show has sparked a response that surprised even the cast. Messages poured in from both sides of the border.

What’s perhaps most striking about Mauj’s work is its refusal to pigeonhole its audience. When they staged Ramayana last Diwali, Karera admits he was nervous. “There’s this assumption: Oh, it’s a Hindu story, so only Hindus will come.” But he pushed hard on the messaging. “I kept saying: ‘Just come watch. It’s your story too’.”

It worked. The audience skewed young and diverse—Muslims, Hindus, millennials, Gen Z, and even parents with kids.

“People came expecting mythology, and they left with something more universal,” Karera said.

The buzz caught on. Encouraged by the response, Mauj decided to scale up for a second run in June 2025, this time at the Arts Council of Pakistan, with better lighting, sound, and AI-enhanced set design.

“Everyone thinks using AI was a tech flex,” Karera laughed. “It was actually budget stress. We couldn’t afford art direction. So we hacked it.”

The play was adapted from the Doordarshan version, with major scenes linked through narration. “We couldn’t stage everything, so we focused on the emotional spine,” Karera explained.

It had a 90-minute runtime and took months of preparation.

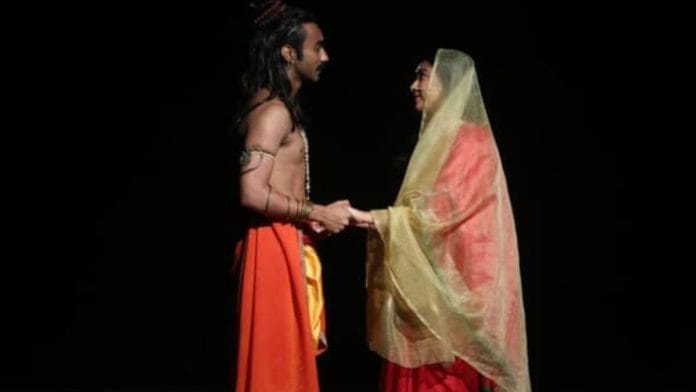

Ashmal Lalwany, who plays Ram, dove deep into research. For him, it wasn’t just a role, it was a responsibility.

“You’re not just playing a character,” Lalwany said. “You’re embodying a belief system for millions. And that means there’s a fine line in how you approach it.”

He studied the source material, read up on public perceptions of Ram, and worked closely with Karera on details like speech patterns and posture.

“Even the way I sound had to match what people carry in their heads as sacred,” he added.

Kazmi, who balances her theatre work with a full-time job in HR, said the idea wasn’t about pushing boundaries. It just didn’t occur to them that it was a boundary.

“None of us ever felt like we were telling a story outside the world we inhabit. I may not be Hindu, but this is a story of our subcontinent. It never felt like it wasn’t ours to tell,” she added.

Culture shock—or not

The response defied expectations. Even within Pakistan’s Hindu community, where Ram Leelas are traditionally performed only in temples during festivals, the Mauj production drew admiration. There was no backlash.

In fact, audience members began asking why certain episodes were left out.

“No one from the audience said, ‘Why are you doing this?’,” said Kazmi. “In fact, the only critique we got was, ‘Why wasn’t Suparnakha shown?’ or, ‘Where were the war soldiers?’”

“We just didn’t have the budget for an army,” Karera said.

Even those sceptical before the show were moved by the end of it. Karera recalled one man who told him he’d grown up on the Doordarshan Ramayana and had brought his kids to watch.

“I was terrified,” Karera admits. “I can’t make Hanuman fly like on TV. How do I match that?”

After the show, the man walked up to him and said that his kids loved it.

Karera, Kazmi and others realised that in a deeply divided subcontinent, if they were navigating reverence and cultural tightropes, the audience was navigating something deeper: Memory.

An elderly woman who grew up in Lucknow and had once watched naataks in open-air theatres gave the cast a standing ovation. “She told us we brought back her childhood,” Kazmi recalled.

Others reacted more viscerally. “A woman came up to me after the show and said she wanted a picture with ‘Ramji and Sitaji’,” Kazmi said. “She was so respectful. I had to say—‘I’m Rana.’ It was surreal.”

Shared history

The realities of indie theatre in Pakistan remain tough. While Ramayana received glowing reviews and generated buzz on both sides of the border, it didn’t magically translate to institutional support or repeat performances.

“It’s hard,” Karera said. “People say, ‘Oh, we missed it! Do it again!’ But doing it again means money, venues, crew, actors—and there’s no guarantee they’ll show up the second time.”

Social media interest doesn’t always translate into ticket sales.

“We get DMs from people in Lahore, Islamabad, saying ‘Please bring it here!’” Karera said. “We’d love to. But it takes more than likes and shares to pull that off. Without consistent funding, we can’t scale. Right now we’re doing intimate theatre. We’re not staging 100 shows in a 450-seater hall.”

And yet, the group isn’t discouraged. If anything, they’re excited by the conversations they’re sparking.

“We’re building something, even if it’s fragile,” Karera said. “Every production is a question to the audience. And the answer we get back, that’s what keeps us going.”

So, will Ramayana return?

“Who knows,” Kazmi shrugged. “Maybe. Maybe not. We are happy with what we did.”

For now, Mauj Collective is quietly crafting a different kind of script—one where stories from across the subcontinent belong to everyone.

“When you’re performing and you see someone in the front row whispering to their child, explaining the scene, that’s the payoff,” Kazmi said.

As Karera puts it: “This is our Ramayana too.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)