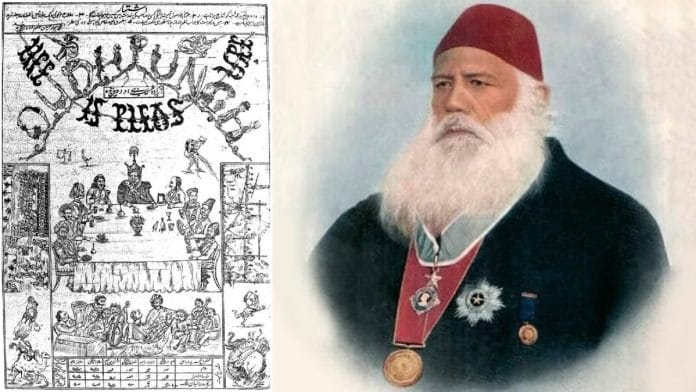

New Delhi: The post-1857 reformist movement led by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan faced intense backlash from Muslim society. However, the criticism from a Lucknow-based weekly established in 1877 was at once creative and ironic. ‘Awadh Punch’, a satirical Urdu magazine modelled on the British magazine ‘Punch’, not only offered a strident critique of the colonial government but also targetted Sir Syed’s modern and scientific beliefs and the parallel reformist movement in Urdu poetry. And it did so using poetry and satire, combining both to create what became known as ‘nechariya poetics’.

The Urdu magazine landed a derogative punch on a regular basis at everything it considered worth ridiculing—colonial modernity, Sir Syed, the natural shayari movement, and Western influences—under the umbrella term ‘nechariya’. According to Maryam Sikander, a Junior Fellow at the Prime Ministers Museum and Library who recently gave a lecture at Teen Murti House in Delhi, the word ‘nature’ became common in the Urdu public sphere after Sir Syed’s “naturalistic commentary on the Quran”, where he sought to interpret the scripture in light of “19th century natural sciences”.

“While this modern and somewhat controversial exegesis notoriously earned Sir Syed Ahmed Khan the uncharitable label of being a nechari, the other subject of ridicule was the poet of the Aligarh movement, Altaf Hussain Hali, who, in his Muqaddama-e-Sher-o-Shairi, sought to reform Urdu poetry by linking reason with nature and expelling hyperbole or mubalga from the rhetorical tropes of Urdu poetry,” she said.

Sikander elaborated that this movement represented a significant shift in Urdu literature. “Natural Shayari, as a movement, sought to redeem Urdu poetry from the abstract exercise of metaphysical contemplation and artificial metaphors,” she explained. This approach aimed to ground poetry in observable reality, a move that was both revolutionary and controversial.

Also read: Maulana Kalbe Sadiq — scholar, educational reformer & ‘India’s second Sir Syed’

Why ‘nature’

According to Sikander, Sir Syed first used the English word ‘nature’ in Urdu in his commentary on the Bible while interpreting the Book of Genesis. He did not use the term in reference to the Quran, nor did he “interfuse it with any spiritual significance like [William] Wordsworth”, as noted by Urdu historian Mohammad Sadiq.

His commentary referenced scientific findings such as microscopes and telescopes, which he argued “justified the world as a rule-based and beneficent order designed, created, and maintained by an all-powerful and all-seeing God”. Sikander noted Sir Syed’s commentary on Surah Yusuf in the Quran, where he posited that “dreams could be explained by modern sciences of psychology and physiology, and Prophet Yusuf’s ability was [merely] a special aptitude.” Similarly, he argued against the existence of miracles, suggesting that everything seemingly inexplicable could be explained through metaphors and allegories “since the time of the Prophet”.

This did not sit well with Muslim intellectuals of the time. The Daily Punch of Lahore, for instance, published Persian verses ridiculing Sir Syed, calling him Satan and apostate or “a betrayer of mankind, a leader of thieves”.

Sikander pointed out that Sir Syed’s use of ‘nature’ was more aligned with English writers who used it as the opposite of whatever is far-fetched, remote, or unreal. “In his later writings and translations, ‘nature’ is used synonymously with Urdu words like qudrat, fitrat, and tabiyat,” she explained, highlighting the nuanced way Sir Syed incorporated this concept into Urdu discourse.

Parallel to Sir Syed’s efforts, Hali emerged as the poetic voice of the so-called ‘Nechariya movement’. He urged Urdu poets to adopt a more realistic, reason-based approach, moving away from the artificial metaphors dominating Persian-influenced Urdu poetry. Hali promoted a mimetic realist mode, insisting that poets draw inspiration directly from nature and everyday life.

In his Muqaddama-e-Sher-o-Shairi, Hali argued that Urdu poetry was threatened by science and civilisation. “Science uski jad kaat rahi hai aur civilisation uska tilism tod rahi hai” (Science is cutting its roots and civilisation is breaking its talisman).”

Also read: Why do Indian Muslims lack an intellectual class? For them, it’s politics first

Awadh’s punches

Writers of Awadh Punch, mostly orthodox Muslims, saw an agenda behind the Aligarh movement. They viewed modernism as another means for the British to enslave Indians. The weekly, founded and edited by Munshi Sajjad Hussain, included writers such as Syed Mohammad Azad, Akbar Allahabadi, Ahmed Ali Shauq Qidvai, and Tribhuvan Nath Hijr.

Awadh Punch routinely published parodic pieces on the Aligarh movement, using titles like “Nechariya Conference Ka Khaka” (Sketch of a Nechariya Conference) and “Nechari Speech”. The magazine also produced many parodic ‘natural’ ghazals or poems.

Sikander highlighted the creative ways in which Awadh Punch critiqued the Nechariya movement. “The newspaper coined terms like ‘Natureabad’ to lampoon the movement’s ideals and published numerous parodic poems that exaggerated the movement’s emphasis on realism and nature,” she said. This approach not only mocked the Nechariya poets but also demonstrated the satirists’ literary creativity.

In 1888, Awadh Punch published a satirical verse titled “Nature ka Asar, Tehzeeb ka Jauhar” (Nature’s Effects, Civilisation’s Essence), aimed at the Nechariya poets and writers. The verse satirised those who embraced Western ideas:

“Jo chor mazhab islam naturee ho jaye,

Mit jaye par duniya me behtareen ho jaye,

Committeeyon me mukarrar secretary ho jaye…

Jab wo bada commissioner ho jaye,

Bulaye ladiya use kehkar come you dear…

Bithaye aankhon par aur shauk se sune lecture…”

(He who gives up Islam and becomes a Naturee,

Believes the world will fare better with a life to come,

In committees an appointed secretary he becomes…

A judge or commissioner he becomes,

Ladies summon him by saying come you dear,

In high esteem, they hold him hearing his lecture…)

“Perhaps the biggest reason for criticising Sir Syed was that he promoted modern education for boys and girls. Along with this, his relationship with the British government wasn’t liked by orthodox Muslims. This is why they used [Awadh] Punch as a platform to criticise Khan,” said Shafey Kidwai, author and professor in the Department of Mass Communications, Aligarh Muslim University.

There was some irony in Awadh Punch criticising Sir Syed’s English ‘outlook’ and association while itself being influenced by a British magazine (Punch).

“Sir Syed not only wanted reform within society but also in literature, where he sought more writers to write on nature, social change, and day-to-day life instead of relying on ghazals and shayari on love and imaginary worlds,” added Prof Kidwai.

Orthodox Muslims also held a grudge against Sir Syed for his “radical views on religion”. Writers like him weren’t only criticised satirically; several fatwas were issued against them as well.

“Miniatures and cartoons of Sir Syed were made in these newspapers. In one, Khan was depicted as the Pied Piper, shown standing on top of a place and playing the flute, leading people who followed him to fall into a ditch,” said Prof Kidwai.

Sikander concluded her lecture by emphasising the lasting impact of the Nechariya movement. “Despite the criticism and satire, the Nechariya movement left an indelible mark on Urdu literature. It challenged long-held conventions, opened up new avenues for poetic expression, and encouraged a more critical engagement with both religious texts and literary traditions,” she said. This controversy, which began with the simple concept of ‘nature’, ultimately played a crucial role in shaping modern Urdu literature and Muslim intellectual discourse in colonial India.

(Edited by Prashant)