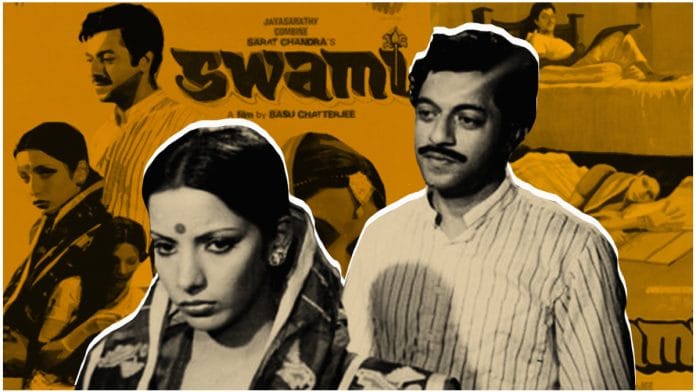

How much can a woman exercise her agency in India’s cultural and social landscape? Even today, the answer is ‘not satisfactorily’. And this is starkly apparent in Indian cinema. But while mainstream Bollywood has finally turned its eyes toward women-centric films in the past few years, parallel cinema has been doing it for decades. Basu Chatterjee’s 1977 film Swami is a prime example of that.

An adaptation of author Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s eponymous book, the film tells the story of Saudamini, played by Shabana Azmi. Saudamini or Mini, as she is called, is a young, highly intelligent, independent woman. She lives with her widowed, god-fearing mother and liberal bibliophile uncle (played by Utpal Dutt). While her mother desperately wants to get the 19-year-old married off, her uncle believes she should study more.

Mini, who agrees with her doting uncle, is smitten with Naren, her neighbour who lives in Kolkata. Unfortunate circumstances lead Mini to be married against her will to Ghanshyam (Girish Karnad), a tradesman, who is the sole breadwinner of an ungrateful family. The opinionated and feminist Mini wrestles with her desire to be set free and adhere to custom.

Chatterjee’s film does take a detour from Chattopadhyay’s book, written in the early 1900s, but only to upgrade it for more modern times. The essence of the story — the protagonist, Mini — is kept intact and brought out in a masterful way.

The story really is just Mini and the conflict within her. She is brought up reading everything from Tolstoy and Jules Verne to Thomas Hardy novels, but is forced to live in a society that does not support any of the ideas she consumes so hungrily. She is constantly torn between her conservative mother and her liberal uncle. Similarly, once she is married and finds herself in an alien situation, she is torn between following her ideals or sticking with tradition — and when she chooses the former, she is instantly met with the consequences of going against the grain.

Also read: Chashme Buddoor, aka Saeed Jaffrey, and the art of making a small role fill the screen

The film makes for a fitting tribute to Chattopadhyay’s feminist writing. He was that rare Indian male writer who chose to tell the story from a woman’s point of view. Many of his stories, which have been adapted into films in various languages, talk about the woman — her life, her emotions, her thoughts, her conflicts. Even a century later, his heroines are extremely relatable. Their angsts, desires, willpower and defiance are validated beautifully in the stories set against the backdrop of society tailored to stifle them. While he did empower them, he also showed them with flaws and shades of grey — he made them human.

Needless to say, Azmi does a breathtakingly beautiful job of playing the conflicted heroine. Her performance is especially remarkable in the scenes in which she is forced to reckon with her relationships with men. When with Naren, it is her first love, which also happens to be forbidden. While she is brave and outspoken, she falters with the anxieties, the secret highs, and the butterflies that come with a first love.

After marriage, Mini’s character arc takes an interesting turn. She comes face to face with an ideal she speaks about confidently at the beginning — once married, a man or a woman has no right to fall in love with someone else.

The way she deals with this dilemma is intriguing to watch. Depression, angst and shame flit across Azmi’s fresh, beautiful face as she silently denies Karnad any kind of marital relation. Anxiously, she rebels against her new husband and his family, and when she finally follows her heart’s desire, she realises that marriage and love are not as black and white as she had naively believed.

Faced with the grey realities of complicated relationships, Mini doesn’t really soften with the heavy guilt she feels, but deals with it in the same passionate and trailblazing way that befits the name Saudamini (meaning lightning).

Also read: 1942: A Love Story — the swansong that brought R.D. Burman back to stay

Chatterjee’s deft directing is visible throughout — the comfortable pace, the subtle heightening of drama, the effective use of symbolism (rushing water to show passion; tragedy personified by soft coils of smoke). The music, directed by Rajesh Roshan, and voiced by Lata Mangeshkar, Yesudas, and Kishore Kumar were hits.

Pal Bhar Mein Yeh Kya Ho Gaya and Yaadon Mein Woh were particular favourites with audiences and even helped the singers and Roshan get nominated for Filmfare awards. And with songs and cameos by Hema Malini and Dharmendra, the film struck that fine balance between parallel and mainstream cinema.