Blind male protagonists have been integral to Hindi cinema, from Rajiv Rai’s Mohra and Vipul Amrutlal Shah’s Aankhen to Sriram Raghavan’s Andhadhun.

But nothing competes with Sai Paranjpye’s timeless gem Sparsh (1980). Paranjpye was a true-blue feminist, who focused on meaningful storytelling through her work. She was the only woman creating art cinema in India in the ’70s and ’80s.

Anirudh Parmar, portrayed by Naseeruddin Shah, is the principal of Navjivan Andh Vidyalaya, a boarding school for blind boys. A man of strong principles, Parmar wears self-respect and dignity as a badge of honour. He instils these values in his students, teaching them to recognise their own worth and capabilities, just like their sighted peers.

“The thought that I would have to act as a sightless person with children who were actually sightless and acting as themselves took me as close to butterflies in the stomach as I have ever been,” Shah wrote in his memoir And Then One Day: A Memoir.

Not only the audience, but Parmar’s school for blind boys is equally new for Kavita Prasad (Shabana Azmi) as well. Kavita is a young widow, who is eager to share her talents in music, drama, storytelling, and handicrafts with the boys.

Parmar manages his daily tasks independently, from pouring tea to walking home. Although he has an assistant, he remains largely self-sufficient. He is able to let go when with Kavita, but his insecurities resurface and intensify after a tragedy strikes his close friend Dubey (Om Puri).

Not many will be able to recognise Puri in the film. The actor, who gave a breakthrough performance in Aakrosh in the same year, has a small cameo. He plays the role of a blind man, whose wife has passed away. Following Dubey’s tragedy, Parmar gets consumed by his ego, following which he ends up pushing his lover away.

Is Kavita trying to be a Gandhari? Is she being great by sacrificing her life? Is she trying to justify her second love as a duty or a charity? Is she with me out of pity? — these thoughts overpower Parmar’s mind.

Compelling visuals

Sparsh opens in an empty corridor, where a boy is reading a chapter from his history textbook. It takes us a moment to realise that he is visually impaired and is using his fingers to navigate Braille. Such compelling visuals are recurring in the film.

The cinematography thoughtfully uses lighting, camera angles, and subtle visual cues to depict Parmar’s world, offering viewers a profound sense of his experiences and emotions.

Another compelling moment is the initial interaction between Parmar and Kavita. The use of close-up shots and soft lighting underscores the tentative yet growing bond between them, conveying a range of emotions from vulnerability to trust.

When Kavita addresses the blind boys as “bechare”, Parmar loses his cool. He firmly tells Kavita to treat them like other children.

It is pretty evident that Sai’s film struggled with budget. Editing isn’t flawless — abrupt cuts and shifts of scenes disappoint the movie-watching experience.

Filmmaker Basu Bhattacharya, who bankrolled Sparsh, didn’t want to release the film. According to TOI, the film was shelved for three years. It was Azmi and Sai who took a vocal public protest against the creative smothering. That’s when the film was released.

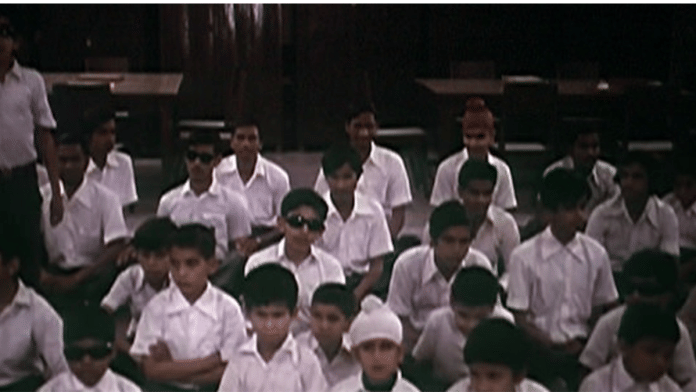

The boys

When served the unappetising food for lunch, the boys in the school voice out their complaints in a funny chant: “Hai re kaisa uljhan, phir se aloo baingan (Oh what a pain, potato brinjal again!)”

The boys of Sparsh are witty, clever, and have spunk. They stuff their pockets with extra sweets, bargain with each other for work (two toffees is the rate for favours), experience jealousy, and seek attention.

Sparsh also highlights that number of books in Braille is abysmally low. It also shows how stories for the blind must make sense to them.

Tales of reflections in water mean nothing to those who have not seen light. Gradually, Kavita learns Braille and manages to print a few short stories for the boys. Along the way, like Kavita, the audience also learns that Parmar was right. None of the blind children need pity.

Sparsh went on to win the National Award for Best Feature Film in Hindi. Shah took home the National Award for Best Actor, while Paranjpye won Best Screenplay. Later, she made hit comedies like Chashme Buddoor (1981) and Katha (1982). “Women actually have a fantastic sense of humour, better than men. Men tend to have crass and predictable humour. Women see human foibles and minute details, and they can laugh at eccentricities and peculiarities,” Paranjpye said in one of her interviews.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)