New Delhi: Joe Sacco had just completed his journalism degree when shocking images of bloodied bodies and bombed-out buildings began pouring in from the 1982 Lebanon-Israel War. Among the dead in Beirut were thousands of Palestinians in refugee camps. For Sacco, the renowned Maltese-American graphic journalist and cartoonist, the images shattered his worldview.

“I thought the Palestinians were terrorists,” he said of the time. Upset and confused, Sacco felt driven to find out what was really happening—firsthand. A decade on, in 1991, he finally set off for Gaza, wandering through the narrow alleys of Khan Yunis to hear stories directly from those living it.

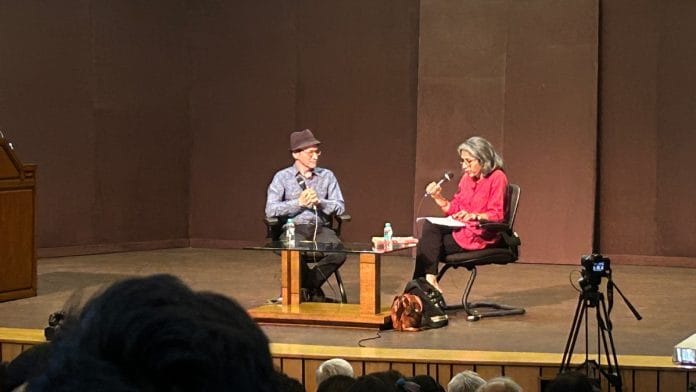

“The gold standard American journalism that I was taught in school actually pulled the wool over my eyes and a resentment developed,” Sacco told a crowd of over 300 at New Delhi’s Jawahar Bhawan on 11 November, during an event titled ‘Drawing a Line’, in conversation with Seema Chishti, editor of The Wire. “A resentment developed (in the West toward Palestine) that led into this pit of misinformation.”

This “misinformation” was something Sacco was determined to break through with his signature mix of hard-hitting ground reporting and graphic art. He spoke about his evolution from cartoonist to graphic journalist and using his work to reveal harsh realities not just in conflict zones but also among Dalits in India.

His most famous works include Palestine, based on his two-month stay in 1991, and Footnotes in Gaza, which documents bloody events during the Suez Crisis. His 2011 work, Kushinagar, on the plight of Dalits in Uttar Pradesh, he said, will be available as a standalone book in English next year. Over the years, his work has earned him multiple awards, including the American Book Award in 1996 and the Ridenhour Book Prize in 2010.

Reflecting on his first trip to Palestine, Sacco said he wanted to bring people’s attention to the 1956 Khan Yunis Massacre, where more than 250 Palestinians were killed during an Israeli invasion. But as he spoke to older survivors back then, younger Palestinians would interrupt and ask why he was talking about a historical event when so much was happening in the present.

“Two hundred metres from there, the Israeli army was bulldozing houses and roads. There is no time for Palestinians to digest a thing because something always is coming at them,” he said.

Also Read: ‘The Last Courtesan’ is a saga of guns, gangs, ghazals. Author didn’t want it to be a movie

Graphic realities

Stories of war were a fixture in Joe Sacco’s childhood. Born in Malta, an island in southern Europe, and raised in Australia—a country brimming with post-war immigrants—he grew up hearing about the hardships his parents had endured. Years later, those World War-II stories found their way into his sketches, particularly his mother’s recollections of travelling from her village to a city called Valletta after winning a scholarship.

“Those were the kinds of stories that I grew up with. And I developed some feelings for what people have to endure,” he said.

While Sacco was pursuing his journalism degree, he first set his sights on becoming a newspaper reporter. But after failing to find a job, he gave up on the idea and decided to fall back on something that he had been doing since he was a child — cartooning.

The two worlds—reporting and art—collided when Palestine piqued his curiosity. On a whim, he decided to travel there to create a graphic travelogue. But once he was on the ground in Gaza, the project began morphing into something more journalistic.

“I began asking questions like a journalist, behaving like a journalist. The artistic side of me and the journalistic side of me came together,” he said.

Decades on, Sacco still describes himself as a “cartoonist”, but the bulk of his work has not been about making people laugh. It’s about using art to reveal hard truths with an investigative edge.

In the field, Sacco acknowledged that he might not look very different from any other journalist: scribbling notes, recording conversations, snapping photographs. Yet, his work is not only more visual but also more personal than most journalism. Often, he even inserts himself into his panels.

“When I was in Palestine, I just became a figure in my comics. I began to understand that having my figure in the panels sort of signals the reader that you’re seeing this through the eyes of a journalist,” he said.

For him, it’s important that a journalist is seen as “a living, breathing human being who is interacting with people and is subject to the forces of conversations”.

Also Read: What brings Indian diplomats together on Nepal, Partition, Durand Line? Empathy

Inking India

Sacco’s connection to India is not new. In 2011, he visited Uttar Pradesh’s Kushinagar to report on the lived experiences of Dalits.

“It was about the schemes that are meant to help the Dalits and how those end up in reality,” he explained. He chose to visit a year after communal riots there, wanting to understand “what people would tell themselves about what they did a year later”.

That same year, his comic Kushinagar was published in the French magazine XXI, as well as in a special issue of The Caravan. Sacco noted that while the book is currently available in French, an English edition is expected to be released in about 10 months because “the wheels of production sometimes move slowly.”

Sacco also played a small yet meaningful role in the acclaimed Indian graphic novel Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability, published in 2011 by Navayana. The traditional Gond artists, Durgabai and Subhash Vyam, were first exposed to graphic storytelling through famous works by Sacco and others. Yet, they ditched the usual boxed panels in favour of their own free-flowing style.

Sacco later endorsed the book on its cover, calling it “challenging in all the right ways”. He also told The Washington Post: “The story was very engaging and done in a style that was completely new to me. I applaud the artists for sidestepping the standard Western comic-book conventions.”

During the New Delhi event, Sacco answered many questions from the audience. When someone asked how civilians around the world can process the ongoing crisis in Palestine, his response was heartfelt.

“I think the point is we can’t process it,” he said. “If we were able to really process it, we wouldn’t really be humans. It’s a real human response to have this really stuck in your throat.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Another white woke speaking about lived experiences. Israel is being bombed by rockets daily. These are not stray terrorist incidences. This is a state of war. All these bleeding hearts need to be asked. If your home was bombed everyday by random rockets, would you ask your government to make peace with the terrorists or fight them. They can hide behind children and then cry victim. There is no sympathy in a leftists eyes for Israeli women and children.