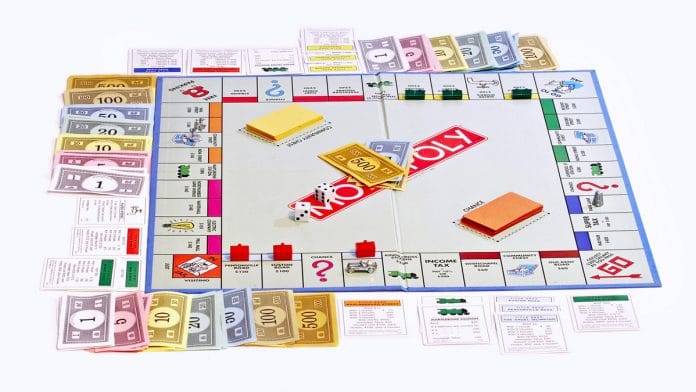

Have you played Monopoly lately? Or maybe snakes and ladders? These board games are examples of 100-year-old games that many still play today.

But the way they are played today may not be teaching the lessons their designers hoped to share.

At the start of the 20th century, children were part of the regular workforce. They possessed few toys. When U.S. manufacturers created games, they built them to market to parents: to teach as well as to entertain.

Progressive writer Elizabeth Magie Phillips created Monopoly in 1904 to teach players about the dangers of wealth concentration. Originally called The Landlord’s Game, it celebrated the teachings of the anti-monopolist Henry George whose widely read book, Progress and Poverty, published in 1879, argued that governments did not have a right to tax labour. They only had a right to tax land.

Monopoly didn’t become a hit until the Depression. Its original message that all should benefit from wealth was transformed to its current version — where you crush opponents by accumulating wealth — by its second developer, an unemployed heating engineer named Charles Darrow. By the mid-1930s, orders for the game had become so extensive that employees of Parker Brothers stared piling the order forms in laundry baskets.

Games with meaning

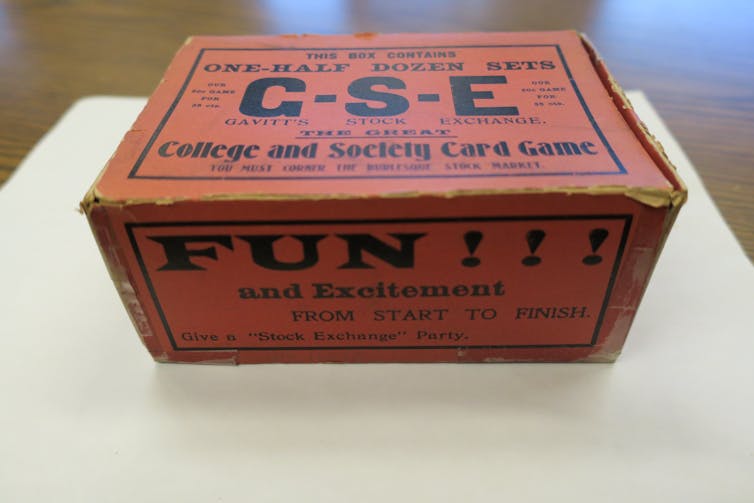

Many of the games in circulation today are more than a century old. Pitt (originally Gavitt’s Stock Exchange) was made during economic panics, railroad failures, speculation and anti-monopoly movements. Patented by Harry E. Gavitt in 1903, the game was designed (as the rulebook says), to reproduce the “excitement and confusion generally witnessed in stock and grain” exchanges.

Players work to gain a monopoly over an economic market. They gather all the copies of one product and inflate its value to reap substantial profits.

Monopoly and Pitt taught economics while Chutes and Ladders focused on morality.

Chutes and Ladders was inspired by games played in South Asia about 1,000 years ago. Many of these games had explicit Hindu religious themes. They had different names: Nepal (Nāgapāśa); Tibet (The Game of Liberation); and India (Jñāna Chaupār). A Buddhist monk, Sa-skya Pandita, created the Game of Liberation for his sick mother in the 13th century. He likely based it on earlier forms of the game he encountered as part of his pilgrimages.

In Nāgapāśa, players attempted to reach a realm of one of the Hindu gods. In the Game of Liberation, they aimed to reach nirvana.

British and American manufacturers stripped the game of its religion, but they kept its emphasis on morality and the game stayed much the same: moving upwards on the board represents good moral decisions; falling back is a punishment for poor choices.

Teaching tools

Toys and games offered a way for teachers and parents to prepare children for their adult lives. Parents used mechanical toys to teach engineering to boys. They used dolls to teach sewing, ingenuity, and household management to girls. It was one way to take complex ideas about society and translate them into forms children could understand.

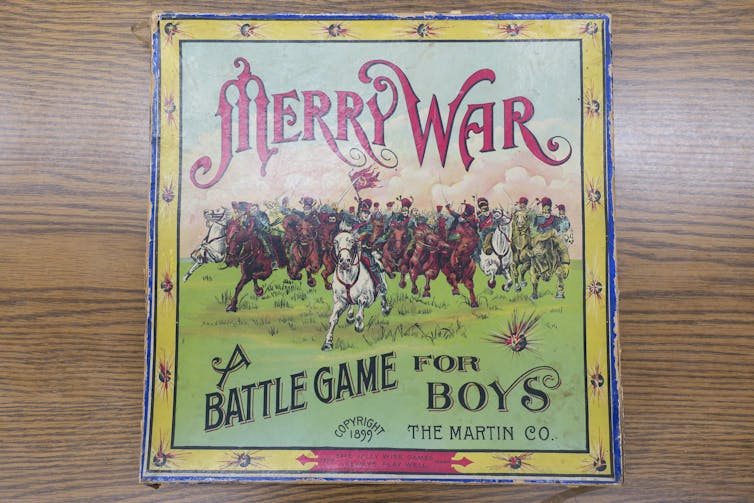

Playing games could also be a way to learn history. During the the Philippine-American War, game designers created Merry War to teach children about the conflict.

In 1899, a newspaper columnist in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote that “toy makers…are as watchful as politicians and scientists to keep abreast of the events of the day.”

Market changes

By the 1960s, manufacturers began to advertise directly to children, rather than to their parents. They emphasized the excitement of their products over their educational value.

At the same time, civil rights unrest, the rise of feminism and rapid technological innovation made the world seem unpredictable. How could you prepare your children for their adult lives when the future seemed so difficult to understand?

Today, lessons remain embedded in many board games, but they sit apart from games just for fun. Board games are no longer a key venue to transmit information across generations.

Yet for all that has changed, we still play these old games, even if we don’t remember their lessons.![]()

Benjamin Hoy, Assistant Professor of History, University of Saskatchewan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.