New Delhi: A dashing young man with a twinkle in his eye burst into Bollywood in the 1940s. Dev Anand had arrived, and Hindi cinema was never the same again. With his impeccably tailored suits, gleaming shoes, slick hairstyle, and that ever-present puff of cigarette smoke, the actor epitomised the metrosexual man decades before the term was coined in the 1990s.

In 1948, his first hit Ziddi—his fifth film—established him as a leading actor. Ashok Kumar, the biggest star at the time, reportedly spotted Anand hanging around in the studio and cast him opposite Kamini Kaushal in the film.

For the young man — born Dharamdev Pishorimal Anand on 26 September 1923 in Punjab’s Gurdaspur district — becoming a film star was a dream come true. Ziddi set off a glorious career spanning six decades, during which Dev Anand, along with Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor, ruled Bollywood as the Trinity—or the legendary ‘golden trio’.

Baazi (1951), CID (1956), Paying Guest (1957), Kala Pani (1958), Guide (1965), Jewel Thief (1967): Anand’s filmography was a captivating mix of romance, suspense, and drama—a true reflection of his dynamic approach toward life and cinema.

“I am a man of the future, not the past. I am a man who is constantly moving on. What is done is done, it is of no interest to me. Let the world discuss it. Dev Anand has already moved on to the next,” he said at an award ceremony in 2009.

Anand will always be Bollywood’s evergreen heartthrob, India’s Gregory Peck. As part of his birth centenary celebrations, the National Film Archive of India and the Film Heritage Foundation restored four of his iconic films: CID, Guide, Jewel Thief, and Johny Mera Naam (1970). They were screened at PVR Inox theatres across 30 cities on 24 and 25 September as part of the ‘Dev Anand@100 – Forever Young’ festival – a fitting tribute to India’s first King of Romance.

Also read: ‘My name is Prem, Prem Chopra’—India’s favourite villain is more than a Bollywood bad…

Optimism & style — Dev Anand staples

Anand was not just a mainstream actor; he was a pioneer of modern Indian cinema. He dared to be different and was unafraid to experiment.

His timeless style continues to inspire fashion aficionados, proving that elegance never goes out of fashion. It was an indelible part of him even during the twilight of his career, when hits were few and far between.

“For me, Dev saab was singularly the most dashing hero in Indian cinema. He had such style, such panache, such a way of moving and speaking and the way he made gestures. It was just lovely,” film critic Anupama Chopra told ThePrint while recalling her interactions with the late actor.

Retirement or taking a break was not part of Anand’s dictionary. His star shone on the dint of hard work. “There was no point at which he felt ‘I have done enough and I should maybe take a little break or even sit back or slow down’,” Chopra recalls.

A humble beginning that kick-started with a small role in Hum Ek Hain (1946) evolved into direction and production. He acted in more than 100 Hindi films (of which he played the lead in 92) and produced 36 films under his Navketan Films banner.

Anand first explored the film noir style with Jaal (1952), directed by Guru Dutt. The story of their friendship is part of Bollywood lore. Anand met Dutt on the sets of Hum Ek Hain in 1946, where the latter was a choreographer. Anand saw that Dutt was wearing his shirt. The story goes that their shirts got swapped in the laundry, and Dutt admitted wearing Anand’s because he didn’t have a spare. It was the start of a strong friendship. They agreed that if Anand produced a film, Dutt would direct it, and if Dutt produced a film, Anand would act in it.

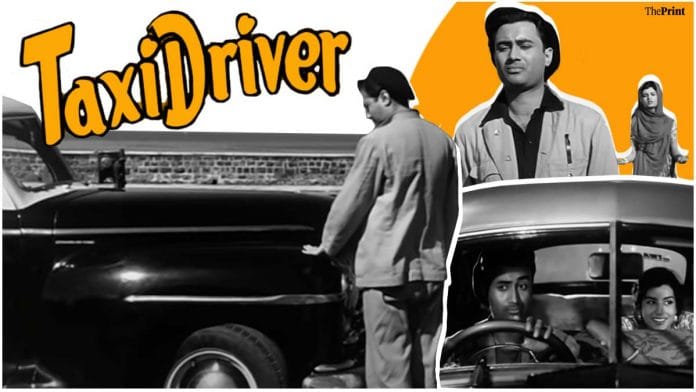

With Taxi Driver (1954), Anand won over the nation playing a carefree, kind-hearted blue-collar cabbie named Mangal. He starred opposite Kalpana Kartik, whom he married in a quiet ceremony while working together on the film.

But before Kartik, there was Suraiya, his first love. Their relationship and its ultimate demise due to pressure from Suraiya’s family is a story as evergreen as Anand. The two actors met on the sets of Vidya in 1948, and he saved her life while shooting the song Kinare Kinare Chale Jayenge in a boat. She fell and Anand jumped into the lake to get her out.

“It was destined that way. Had I gone to her, my life would have been different…Then maybe I would not have been the Dev Anand I am today,” he wrote in his autobiography, Romanicing with Life, published by Penguin India in 2011.

Also read: ‘Duchess of Depression’ Leela Chitnis paved the way for Nirupa Roy, Lalita Pawar in…

The making of Guide

Dev Anand dared to dream big, which was epitomised by Guide (1965), a film shot in both Hindi and English. Based on RK Narayan’s novel, The Guide. It was directed by Anand’s younger brother, Vijay Anand, and starred Waheeda Rehman. The English iteration of this film was written by Pearl S Buck and was directed and produced by Tad Danielewski. It premiered at the Lincoln Art Theatre in New York in February 1965 but failed to make an impact at the American box office.

The Hindi version was plagued with problems, too. Lyricist Hasrat Jaipuri was replaced by Shailendra, and music composer SD Burman suffered a heart attack. He suggested that Anand get a new composer, but the actor, also the producer of the film, waited for him to recover. To make things worse, Narayan was unhappy with both versions of the film.

Despite roadblocks, the film turned out to be a roaring success, winning three Filmfare awards and becoming India’s official entry to the Oscars 1966.

Guide also boosted the career of Waheeda Rehman, who became a part of the film after much drama—first, her refusal, followed by both directors’ rejection. “Then, Dev said, ‘I don’t care. My Rosie is only Waheeda’,” revealed Rehman.

Anand kept working and making films and was entwined in Bollywood’s DNA until his death on 3 December 2011.

Also read: ‘Leke Pehla Pehla Pyar’ dancer Sheila Vaz was ’50s icon but Bollywood forgot to…

An unstoppable force

Chargesheet, starred, directed, and produced by him, was his last film, released in September 2011, a few months before his demise. It met the same ill fate at the box office as all his films after Des Pardes in 1978. In over three decades since his last hit, India won two World Cups in men’s cricket, the world witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union, LK Advani stood on top of a rath for the sixth time, and the US elected its first African-American president.

But all the 17 misses did not dim his shine. While critics and fans panned Chargesheet, Anand remained unperturbed. His optimism knew no bounds. “I am proud of the movie. Even Guide did not do well in the beginning but picked up later,” he had said at the time.

Some associates and industry insiders labelled it as an “expensive hobby” he couldn’t shrug off. Trade analyst Taran Adarsh is fascinated by the question of why and for whom Anand continued to make films. “I had posed the question to him, and the answer was: Log mujhe pyaar karte hain (People love me),” Adarsh told Economic Times in 2011.

And Anand was not wrong. He never had difficulty financing his films, courtesy his die-hard fans in India and abroad who were simply content with the idea of being associated with their star idol in some way or the other, according to film trade analyst Komal Nahta.

This goodwill within the industry and outside helped him get the biggest names for his projects – Jackie Shroff and Naseeruddin Shah (in Chargesheet), Aamir Khan (in the 1990 film Awwal Number), Rishi Kapoor and Salman Khan (in the 2003 film Love at Times Square), and Boman Irani (in the 2005 film Mr Prime Minister).

Anand was also Bollywood’s ultimate starmaker. From Tina Munim, Tabu, Neeru Bajwa, Zeenat Aman to Sahir Ludhianvi, Anand also launched many newcomers to greatness.

“When entering an industry like Bollywood, every actor hopes for a starmaker. Someone who sees the glimmer of potential and ambition that has perhaps only been visible to the self thus far. Very few are so lucky as to find this person, but I was. My starmaker was Dev saab,” wrote Zeenat Aman on Instagram.

Tryst with politics

As a superstar and India’s heartthrob, Dev Anand could have easily remained in his gilded world. But he chose not to, and it came at a heavy price.

According to journalist and author Rasheed Kidwai, Anand refused to say a few words in praise of Sanjay Gandhi and the Youth Congress. His protests during the Emergency saw his films banned on television with no references to him or his work on All India Radio. “The actor could present a grim visage too when provoked,” wrote Kidwai in Neta Abhineta: Bollywood Star Power in Indian Politics.

Kidwai also included Anand in his book Leaders, Politicians, Citizens: Fifty Figures Who Influenced India’s Politics. And with good reason, too. When the Emergency was finally lifted, Anand decided to fight back and “teach the politicians a lesson”. Not one to simply lend his name to a cause, he launched the Nationalist Party of India.

“If MGR could spell magic in Tamil Nadu, why not me in the whole country,” he had told his supporters, who included Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit,” writes Kidwai.

There was a press conference at the Taj, attended by the likes of GP Sippy, Hema Malini, Shatrughan Sinha, and Sanjeev Kumar. And there was also a rally at Mumbai’s Shivaji Park.

“What if all villages are transformed into neat small towns flashing with electricity and gushing merrily with water facilities? What if English is taught to all and farmers, labourers, coolies and aristocrats move around in cars, waving at each other in a spirit of bonhomie,” Anand wrote in his autobiography.

The party and his plans fizzled out, but Anand was always in tune with the politics of his time.

He was on the historic bus ride to Lahore with then-Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, along with Kuldeep Nayyar, Javed Akhtar, Kapil Dev, and Shatrughan Sinha, among others. It was only fitting considering Anand had left Lahore for Bombay to seek stardom, and still has a legion of fans in Pakistan, including former prime minister Nawaz Sharif.

Vajpayee’s private secretary, Shakti Sinha, shared anecdotes of the ride in his book, Vajpayee: The Years That Changed India. According to him, when the bus reached Lahore and Vajpayee and Sharif hugged each other, Anand started recalling stories of his time in the city. He would have carried on “till we gently guided him away,” wrote Sinha.

But it wasn’t his first visit to another country with a prime minister. Anand accompanied Nehru to the Soviet Union along with Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar, Nargis, and other stars.

(1954) Dev Anand, behind him is Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Nargis, Bimal Roy, Raj Kapoor, Nirupa Roy & Anil Biswas in Soviet Russia – PM Nehru’s 14 member delegation for Moscow Film Festival pic.twitter.com/C7sASjCfQ5

— Film History Pics (@FilmHistoryPic) February 19, 2020

Anand had an innate charm that allowed him to say what no one else dared.

In 1962, the actor, then 39, had asked Nehru: “Is it true, Sir, that your devastating smile stole the heart of Lady Mountbatten?”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)