New Delhi: Artist Naina Dalal was painting nude portraits at a time when only men were doing so.

It was London in the 1960s, and Dalal was straddling both Indian and Western art worlds. While her work was well-received in the West, commercial galleries in India largely ignored her. Her art explores the human condition—her gaze on women.

“Perhaps due to my first-hand exposure to modern Western art in the early 1960s, I was making art that the audience in India was not ready for,” she told ThePrint.

The nudes she painted range from ambiguous forms of pregnant bodies to women appearing frozen in anxiety. Her work is poignant and striking, with a sense of nostalgia seeping through some of her earlier paintings from the 1960s when she had just moved to London.

“I always showed my work on my own [in India]. Gallery-sponsored shows were few and far between,” she said.

Dalal, who is almost 90, developed her art at a time when the first wave of feminism was still gathering strength and female artists in India were beginning to be taken seriously. But her themes, ranging from motherhood to loneliness, did not resonate with Indian audiences.

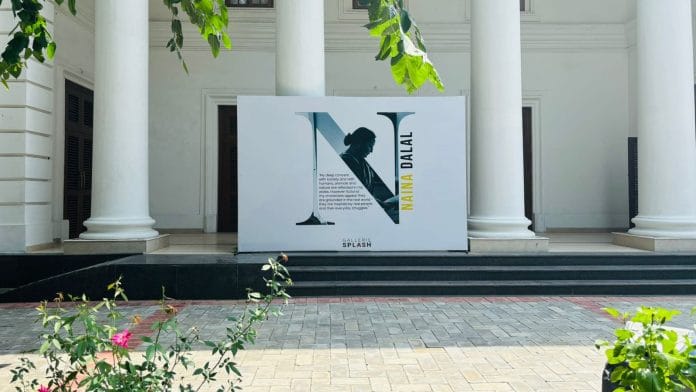

That’s changing for Dalal now: a week-long exhibition of her works, curated by Girish Shahane and hosted by Gallerie Splash, is being held at the Travancore House in New Delhi from 13 September to 21 September. And according to Shahane’s note explaining the exhibition, “The passing of decades lets us appreciate her accomplishments in a clearer light, without the distorting effect of once-polarising debates.”

The exhibition is like a mini-retrospective, providing a sense of Dalal’s extensive output — she created hundreds of works across various mediums. The idea for this exhibition came from gallerist Jinoy Payyapilly, who reached out to Shahane earlier this year.

The request from a gallerist and curator thrilled Dalal and her family, which includes eminent artist and art historian Ratan Parimoo and their daughter, Gauri Krishnan, also an art historian and museum specialist. Dalal was overwhelmed by the response when she visited the exhibition on 14 September. She enjoyed it so much that she made another stop the following day on her way to the airport to return to Baroda, where she lives and works.

“She loved it!” said Krishnan over the phone. “When she came to the gallery, she asked ‘Did I do all these works?’ I think the greatest joy for an artist of her age is to see her works on the wall of a gallery,” she said.

And the exhibition, titled ‘Naina Dalal: Solitary Companions,’ is spread across four rooms, displaying works that explore the inner lives of her subjects — women, men, and animals.

“The retrospective she deserves should be at the NGMA,” said Shahane. “Her work was far too ignored.”

Ahead of her time

When Dalal and Parimoo moved to London in the early 1960s, they saved money to buy tickets to museums and art galleries. They’d share a sandwich but splurge on tickets, according to Krishnan.

“They travelled a lot across Europe — in fact, they were one of the first Indian artist couples to see Western art first-hand and absorb it,” said Krishnan. “That absorption manifested in her creative work.”

The three major classical art traditions include nudes, still life, and landscape. However, the nude has traditionally been the domain of male artists, who typically paint the female form. Dalal’s work was therefore quite unusual at the time, often viewed through the lens of the myriad artistic influences she encountered.

“She wasn’t consciously creating nudes. To her, it’s the most expressive elemental human form,” said Krishnan. “She isn’t trying to make them look appealing; they’re just normal human bodies. And she glides from clothed to unclothed in a very unselfconscious way in her art.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, as sex-selective abortion — female infanticide — became a feminist issue, Dalal created art in response. Her approach was sensitive, direct, and visceral. In one piece called “Maa mujhe jine do,” a single fist holds up a squealing infant, its hands raised to the sky. In the background are female foetuses that never left the womb. In another piece titled “Hope”, a single glowing infant is held aloft.

In another work titled “Homeward”, a woman carrying hay is accompanied by a daughter with doleful eyes. Dalal painted what she knew, said Krishnan.

She also aimed to tell the stories of ordinary people, exploring themes relatable across the human condition. But Krishnan feels that not many understood her practice — even the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) has only one of her works in its permanent collection of prints.

“When it comes to her kind of art, India didn’t have markets or museums mature enough to accept or understand her work,” said Krishnan. “That’s probably why it has taken so long for her to receive the due recognition that she has always deserved.”

A master of mediums

Another aspect that sets Dalal apart from other prominent Indian female artists is her work with printmaking — both lithographs and collagraphs.

Dalal moved to London with Parimoo when he received a Commonwealth scholarship, which made him the first Indian artist to study Western art in London.

She wanted to enrol in a painting course at the London Polytechnic, but the class was full. Dalal wouldn’t take no for an answer — ultimately, the college offered her a spot in a printmaking course instead.

Printmaking is also considered a male-dominated medium, involving heavy machinery and physical engagement with the art. But Dalal felt her gender did not restrict her ability to create the art she wanted.

“No, I was never conscious of that fact [my gender] nor treated it as a stumbling block. I took to printmaking like a fish to water,” she said. “I was very keen to master the techniques of lithography on large blocks of stone, etching and intaglio on metal, and collagraphy, which I developed in my own style — I always found them more exciting as they were tactile,” she said.

Dalal explained that she explored similar themes across different mediums, often starting with sketches and drawings before deciding which medium suited each theme best.

“Sometimes I am spontaneous in choosing the medium, so it’s intuitive at times,” she said.

Her versatility across mediums is what makes her work exciting for historians and gallerists alike. Payyapilly, for example, notes how her collagraphs and lithographs on the same theme evoke completely different reactions. Her earlier paintings, which started off textured, including her nudes, were similar to the textured paintings of that time, according to Shahane.

Not only did she adapt and change, but she also experimented liberally and fearlessly.

Krishnan noted that nothing hampered her creative spirit, despite a tepid reception from the art world compared to other artists of the Baroda School.

“An artist of Dalal’s calibre and prolificness deserves to be collected by museums and galleries not only in India but the world over,” said Krishnan. “It is seriously the best time to acquire her art. Her indomitable spirit and her ‘shade of feminism’ will always remain silently thought provoking but arresting and unshakeable.”

(Edited by Prashant)

Also read: Every Delhi house has a story to tell—the Mughals, Partition and migration

Mediocre artists with overblown egos always think that the “nation/society is not yet ready for their art”.

It’s a convenient way of putting the blame for possible failure in career on society/nation.